CREATURES OF PHILIPPINE MYTHOLOGY: Episode Three

What always fascinates me most about the Creatures of Philippine Mythology, is where the origins came from and how they were integrated into early animist beliefs. During a lunar eclipse in the ancient Philippines, it was believed that a monstrous dragon was attempting to swallow the moon. Watch our new 14 minute documentary and discover the origin of this giant serpent and how the colossal being evolved as both a god and demon throughout the archipelago.

This episode posed a lot of difficult challenges and raised more questions than answers, so I’ve included some supplementary information in this post for those wishing to learn more. I am always open to feedback and I am always hoping to learn more. Please feel free to leave a comment and contribute to the discussion.

Legends of Bakunawa

Most of the recent literary interpretations of Bakunawa can be sourced to renowned folklorist Damiana Eugenio’s re-telling of the myth in her collected compilation “Philippine Folk Literature: The Myths“. This, however, was imagined from an earlier documentation by Fernando Buyser, a Philippine poet, publisher, and priest. Buyser documented the story “Ang Bakunawa” as almost a catechism and referenced verses from Revelations within it. Given the differences between Buyser’s and Eugenio’s story, we can assume she took artistic liberties in the re-telling. This causes me to question the authenticity and historical importance of its content as “folklore”. That said, questioning it is really all we can do since there are no other documented narratives of Bakunawa prior to this time. Such is the challenge of examining oral folklore. We need to sift through volumes of historical information, in hopes of piecing together an accurate picture of the creative minds who shaped the foundations of ancient societal and cultural beliefs. Even still, that window may only represent a very brief moment in time, as the very nature of oral storytelling is adaptive. Damiana Eugenio herself has suggested that many stories in Philippine Folklore would be better classified as “fairy tales”.

Ancient Ilongo Calendar

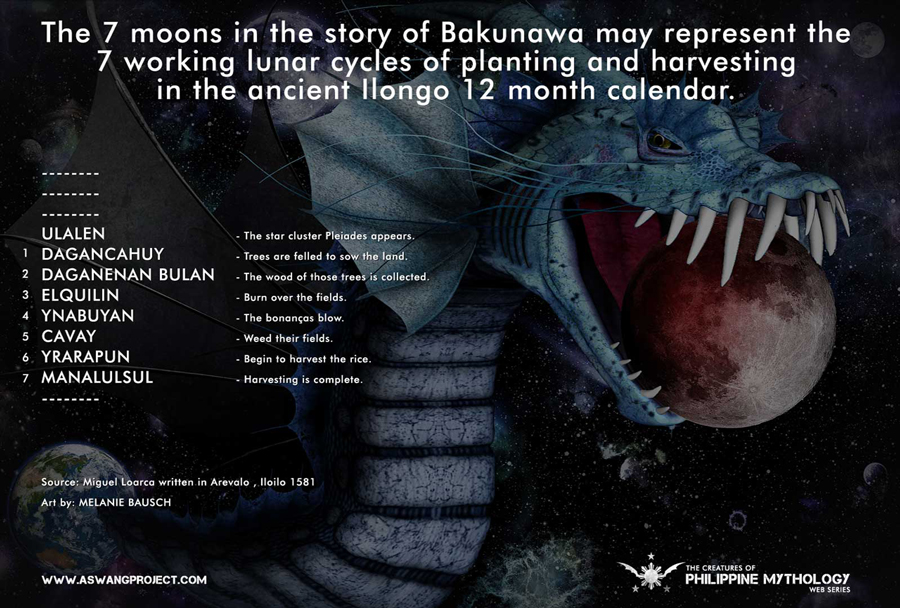

It is suspected that the ancient Ilongos believed there were 7 moons created by Maka-ako (Creator) to light the night sky. One hypothesis for the 7 moons in the story of Bakunawa is that they represented the 7 months for planting and harvesting in their 12 month lunar calendar. The practice of starting a month at the first sighting of a new moon was observed by many ancient societies – including the Romans, Celts, and Germans in Europe and by Babylonians and Hebrews in the Lavant. All of these peoples, like the Ilongos, began their month when a young crescent was first seen in the sky. In “Relation of the Filipinas Islands”, Miguel de Loarca states about the Ilongos of Panay Island:

“Years and months. They divide the year into twelve months, although only seven [sc. eight] of these have names; they are lunar months, because they are reckoned by moons. The first month is that in which the Pleiades appear, which they call Ulalen. The second is called Dagancahuy, the time when the trees are felled in order to sow the land. Another month they call Daganenan bulan; it comes when the wood of those trees is collected from the fields. Another is called Elquilin, and is the time when they burn over the fields. Another month they call Ynabuyan, which comes when the bonanças blow. Another they call Cavay; it is when they weed their fields. Another they call [Cabuy: crossed out in MS.] Yrarapun; it is the time when they begin to harvest the rice. Another they call Manalulsul, in which the harvesting is completed. As for the remaining months, they pay little attention to them, because in those months there is no work in the fields.” (*This could explain the significance of the number 7, but certainly allows for speculation on the importance of the moon to ancient Ilongos)

Belief in Bakunawa

We can assume, with certainty, that the ancient Visayans did practice the custom of banging drums during a lunar eclipse to force Bakunawa to release the moon. We base this on the fact that most of the surrounding countries have similar beliefs. We can couple this with the first documentation about Bakunawa in 1628 by Fr. Alonso de Mentrida, who was an Augustinian missionary in Ogtong ( Oton) , Xaro ( Jaro) , Baong ( Dingle) and Pasig ( Passi). In his “Diccionario de la lengua Bisaya Hiligueina y Haraya“ (Dictionary of the Bisayan Language Hiligaynon and Haraya) he states on Page 38:

Bacunaua “Entendieron que era sierpe que se iba tragando la luna la sumbra de la tiera que la cubre en los eclipses” they believe it was a serpent (Dragon) swallowing the the moon from the earth that presents in eclipses.

” binacunauahan ang bulan.” (Hiligaynon) —- moon has been swallowed ( English)

“Sinuban ang bulan sang bacunaua”( Hiligaynon) —- The moon is swallowed by bacunaua ( English).

The Importance of Bakunawa in the Ancient Philippines

The common assumption is that the belief in Bakunawa is an indigenous legend, and has been a part of ancient astronomy and rituals in the Philippines since people first arrived to the region. In reality, stories of Bakunawa are directly linked to the Hindu demi-god “Rahu”, from India’s Vedic period ( c. 1500 – c. 500 BCE) and was brought to SE Asia through trade and the expansion of the Indianized Kingdoms around 200BCE. The stories travelled to areas of the Philippines through trade and subsequent migrations between 200-900CE. Evidence of Rahu being brought to SE Asia also exists in Javanese Mythology, Thai Mythology, and other Hindu influenced areas such as China. (learn more: 4:10 in the Bakunawa Documentary above)

-(+-another-(sketch),.jpg)

As mentioned in the documentary, the image of Bakunawa was reflective of the surroundings. Giant reptiles were a prominent part of ancient rituals in the Philippines. When researching this in conjunction with Bakunawa, it could lead to conclusions seen as important findings or as wildly speculative assumptions. Again, in societies with oral traditions, the cultural importance of mythical beings is difficult to prove, which leaves a lot of room for artistic license. One reason Bakunawa is seen as such an important figure in Visayan Mythology is because of its apparent depiction on the hilts of the ancient Philippine sword, known as the Kampilan. The truth is, it’s unknown whether the serpent on these weapons represents a crocodile, snake, Bakunawa, or other mythical Nāga (Sanskrit word for a deity or class of entity, taking the form of a very great snake or serpent). We may never know, but it is worth mentioning a few things Miguel de Loarca pointed out in his documentation of Panay Island in 1582 regarding the reverence of crocodiles.

“These natives have a method of casting lots with the teeth of a crocodile or of a wild boar. During the ceremony they invoke their gods and their ancestors, and inquire of them as to the result of their wars and their journeys. By knots or loops which they make with cords, they foretell what will happen to them; and they resort to these practices for everything which they have to undertake.”

“For a few years past they have had among them one form of witchcraft which was invented by the natives of Ybalon after the Spaniards had come here. This is the invocation of certain demons, whom they call Naguined, Arapayan, and Macbarubac. To these they offer sacrifices, consisting of coconut-oil and a crocodile’s tooth; and while they make these offerings, they invoke the demons.”

“It is said that the souls of those who are stabbed to death, eaten by crocodiles, or killed by arrows (which is considered a very honorable death), go to heaven by way of the arch which is formed when it rains, and become gods.”

“Crocodiles. There are enormous numbers of crocodiles, which are water-lizards. They live in all the rivers and in the sea, and do much harm.”

This may lend itself more to the idea of the Kampilan hilt being a crocodile rather than Bakunawa, but it is certainly not definitive. The one thing that weapon experts can agree on, is that there is not nearly enough information available about the Kampilan to make a conclusion about what the image on the hilt represents. Even still, this type of Kampilan is categorized as a crocodile.

In closing, I subscribe to the theory that the Philippines was populated through several migrations. One of these saw the Visayas and Bicol regions populated from a Malay migration between 100-500CE. I think it is this particular migration that brought the belief of Bakunawa swallowing the moon. It would also explain why other migrations, such as the Austronesian Expansion (directly populating the Northern Philippines) did not have the same belief. Further, it may shed light on why subsequent Malay migrations to the Southern Philippines believed in a more birdlike moon-eating being, known as Minokawa. A reserved estimate could date the Filipino belief in Bakunawa back 1500 years. Since Hinduism was still a relatively new addition to the SE Asia landscape at that time, it was possible for the belief to assimilate into oral tradition and become something beautiful, majestic and uniquely Filipino.

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.