The Tagalogs believed in a single, all-powerful God. “Like all primitive religions, that of the Tagalog was,” says Father Horacio De La Costa, “closely interwoven with their culture and traditions. It governed not only ritual and sacrifice, feast and festival, but almost the entire life of the individual and the community. It covered household tasks, planting and harvesting, traveling and hunting, war and love with a network of prescription and tabus. It was the burden of song and story; indeed, it was by stories heard in childhood, songs pounded on the festive board, chants beating time to the oar that it was chiefly transmitted. This, rather than any reasoned conviction, was the source of its strength and vitality. In a primitive culture religion touches everything; there is nothing completely profane. The Tagalogs conceived his universe. Behind it all was a figure dimly discerned in origin, the maker of heaven and earth: Bat-hala Meikapal, Bat-hala The Fashioner. But little was known about this beneficent being; only fitful glimpses of him came through the hosts of jealous and exigent. Anito filled the foreground of the spirit world.”[1]

The Moros[2] of the Philippines have the belief that the earth, the sky and everything therein were created and made by only one God, which they call in their tongue Bachtala napal nauca calgna salabat,[3] which means God the creator and preserver of all things. They call him by the other name of Mulayri.[4] They say this is their God in the atmosphere before there was sky or earth or other things, that it was eternal, and not made nor created by anybody; that he alone made and created everything we have, said solely on his own will, to make something as beautiful as the sky and the land, and that he did it, created from the earth a man and a woman from whom all men and generations in the world have descended.[5]

“They say further that when their ancestors had news of this god which they have as for their highest, it was through some male prophets whose names they no longer know, because as they neither have writings nor those to teach them,[6] they have forgotten the very names of these prophets, aside from what they know of them who in their tongue are called tagapagbasa nan sultan a dios; which means readers of the writings of god; from whom they have learned about this god, saying what are already told about the creation of the world, people, and about the rest. This they adore and worship and in certain meetings held in their homes—because they have no temples for this purpose nor are used to it—they have feasts where they eat and drink splendidly; in the presence of some persons whom they call in their tongue catalonas who are like priests.”[7]

Antonio de Morga is quite emphatic in his observation when he points out that “in matters of religion, they (natives) proceeded in primitive fashion and with more blindness than in other matters, for the reason that, aside from being Gentiles, without any knowledge of the true God, they did not take pains to reason out how to find Him, neither did they envision a particular one at all…There were those who worshipped a certain bird with yellow color which lives in the mountains, called Batala …”[8]

Morga criticizes other chroniclers’ findings, noting the following: “‘Blue bird,’ says the Jesuits Chirino and Colin who in their capacity as missionaries ought to be better informed, of the size of a thrush that they called Tigmamanukin they assigned to him the name Bathala. Well now; we don’t know any blue bird either of this size or of this name. There is a yellow bird, though not completely so, and it is kuliawan or golden oriole. Probably this bird never existed and if it existed at one time, it must have been like the eagle of Jupiter, the peacock of Juno, the dove of Venus, the different animals of Egyptian mythology, that is, symbols which the populace and the ignorant laymen confuse with the divinities. This bird, blue or yellow, would be the symbol of God the Creator whom they called Bathala May Kapal, in the words of the historians, that is why they would call him Bathala, and the missionaries who had little interest in understanding things in which they did not believe and which they despised, would confuse everything as an Igorot or a Negrito would do should he or she worshipped the image of the Holy Ghost or the symbols of the Apostles represented at times only by a bull, an eagle, or a lion, and would relate in the mountain among the laughter of his friends that the Christians worshipped, a dove, a bull, a sparrow hawk, or a dog as those symbols appear represented many times’”

The expression anito was used by the chroniclers of the time to describe the ‘lesser-deities,’ as there does not seem to be a word in Tagalog for them. Father San Buenaventura (1613, 255) commented of Bathala, “According to some he was considered to be the greatest of their anitos. ”Some of them had names descriptive of their functions”, which you may see in this link.

This deity’s true name is yet to be discovered. It was given as Batala in “Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas” (1582) by Miguel de Loarca; Bathala mei capal in” Relación de las Islas Filipinas” (1595–1602) by Pedro Chirino; Badhala in “Relacion de las Costumbres de Los Tagalos” (1589) by Juan de Plasencia; Bachtala napal nanca calgna salahat (“God the creator and preserver of all things”), Mulayri, Molaiari, Molayare, and Dioata in the Boxer Codex (1590); Anatala and Ang Maygawa in“ Carta sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros circunvecinos” (1686-1688) by Felipe Pardo, O.P. ; Bathala mei Capal and Dinata in “The history of Sumatra: containing an account of the government, laws, customs and manners of the native inhabitants, with a description of the natural productions, and a relation of the ancient political state of that island.” (1784) by William Marsden.

The ambiguous nature and confusion surrounding Bathala has left room for this deity to be reinvented. During the 19th century, the term Bathala was no longer in religious use. In its place Panginoon (Lord) and Diyos (God) were used in esoteric religions involving the Infinito Dios and others.

Most would agree that Bathala was derived from the Sanskrit word bhattara or bhattaraka (noble lord), which appeared as the sixteenth-century title batara in the southern Philippines and Borneo. It may be worth noting that in Malay, betara means holy, and was a title applied to the greater Hindu gods in Java and was also assumed by the ruler of Majapahit.[9]

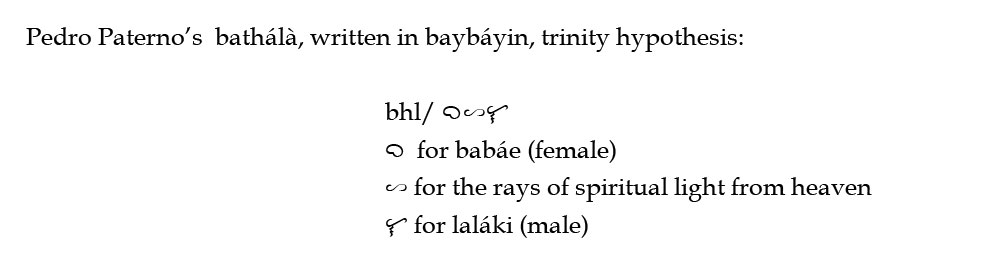

Pedro Paterno (1915 in Pambid 2000:108), analysing bathálà written in baybáyin, bhl/- considers that the /b/ stands for babáe “woman / female”, the /l/ for laláki “man / male” and the /h/ (artificially turned vertically) for the rays of spiritual light beaming from heaven or the Holy Spirit of God. According to him, this would have been the concept of the Holy Trinity before the arrival of Christianity in the Philippines.[10]

Countering Paterno’s theory on Bathala, Jose Rizal wrote to his friend Ferdinand Blumentritt, “In regard to the work of my countryman P.A. Paterno on Bathalà, I tell you, pay no attention to it; P.A. Paterno is like this: [here Rizal drew a line with a series of loops]. I can find no word for it, but only a sign like this: [more loops].”[11]

Adding to the confusion, Americans began documenting myths and folktales at the turn of the century. It is unknown whether the Tagalogs recounted creation tales using the name Bathala for the myths, or if the translators and documentarians took the liberty to add the creator’s name after reading popular entries on the subject from Paterno and Blumentritt, despite the latter’s detailed entry.

Bathala. This name, of Sanskrit origin, is given or was given to various gods of the Philippine Malayans. The early Tagalogs called their primary God Badhala or Bathala mey-kapal, and gave the same name to the bird Tigmamanukin. The Pampangos called a bird Batala, upon whom, according to Dr. Pardo de Tavera[12], they had their superstitions. The Tagalogs sometimes gave the same name Badhala or Bathala to comets or other celestial bodies that, according to them, predicted some occurrence. Bathala was also a good anito of the early Bicolanos, a kind of guardian angel. (See Katobobo). In the religion of the Mandayas (island of Mindanao), there is a god Badla, only son of Mansilatan, who preserves and defends people against power and trickery of the demons Pudaugnon and Malimbung. –The early Visayans named the images of their gods or diwatas, Bathala or Bahala.[13]

When F. Landa Jocano used the name Bathala as the creator when he attempted to simplify the Tagalog pantheon, he assigned a male gender. Not only does he continually use the pronoun ‘he’, but also gave him three daughters from a mortal woman.[14] Jocano also republished the Spanish Chronicles and replaced all the varied names of the Supreme Deity with Bathala.[15]

Whatever Rizal thought, the entry of Paterno caused many to suppose that Bathala was ‘genderless,’ while others claim that he was male. It’s also possible that the chroniclers made the presumption that the creator was male and wrote their documentation accordingly. If one looks, they may find several presumptions made by early chroniclers which are similar to Morga’s criticism earlier in this article. It should also be noted that the ‘genderless creator’ theory, which is based on Paterno’s analysis of baybáyin, may only be correct if the creator deity’s name was indeed Bathala. This is unclear, as previously mentioned, so we should leave room to explore all possibilities.

The name Bathala may have simply been a misunderstanding of the first chroniclers. In another letter to his friend Ferdinand Blumentritt, Rizal wrote that the word Bathala is an error of Chirino or some missionary older or ahead of him. He believed that the phrase Bathala Maykapal is nothing more than the phrase Bahala ang Maykapal, wrongly written, because Bahala ang May Kapal means “God will take care”. The fact that the phrase Bathala May Kapal is often encountered, made him presume that it may be only a copy, and that there cannot be found another source where the word Bathala is used but without the denomination May Kapal. He believed that the Tagalogs never pronounced the name of their God. That they only called him Maykapal, a designation still used and understood by any Tagalog.[16]

This may have been the origin of the Bahala na philosophy of life, which means “come what may,” “whatever will be, will be,” or “leave it to God.”

SOURCES:

[1] The Jesuits in the Philippines, 1581-1768, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1961, p. 40.

[2] The following is an explanation of the terminology: “After the Spaniards arrived here we thought that they were Moros, and that they had some rites of Mahomet, because we found among them many signs thereof, on account of (the fact) that the natives of island of Borney came to these islands to trade. These (people) from Borney are Moros like the Berbers and follow the law of Mahomet, which they began teaching (the natives of) the Philippines, such as circumcision and not eating the flesh of pigs and other minor laws of Mahomet.” Quirino and Garcia, The Philippine Inhabitants of Long Ago, p. 419. Loarca uses the same term for the natives “in the vicinity of Manila.”

[3] Vide, Blair and Robertson, Vol. V, p. 171. This appears to be garbled quotation of Bathala na may kapangyarihan sa Ishat (God the Almighty). Read Quirino and Garcia, op. cit., p. 419, footnote.

[4] Tagalogs would rather say May-ari. Cf. fn. 119 Loc. cit. or an indirect appellation of God. Fr. Chirino in his “Reiscion de las Istas Filipinas”, Blair and Robertson, op. cit., Vol. XII, p. 263, writes:

“In…barbarous songs they relate the fabulous genealogies and vain deeds of their gods—among whom they set up one chief and superior of them all. This deity the Tagalogs call Bathala meicapal, which means ‘God the creator or maker.” Fr. Colin in a similar vein also calls the supreme God of the Tagalogs Bathala meycapal, which signifies ‘God’ the ‘creator’ or ‘maker.’ Blair and Robertson, op. cit., Vol. XL, pp. 69-70.

[5] Quirino and Garcia consider this belief as “undoubtedly the result of the Christian influence upon the natives and cannot be considered as indigenous.” Vide, Ibid., fn. p. 420.

[6] Pre-Colonial RELIGION, CULTURE & SOCIETY of the TAGALOGS

[7] Quirino & Garcia, op. cit., p. 420.

[8] Historical Events of the Philippine Islands, pp. 290-292. Rizal says, seemingly irritated by all the observations of the Spanish chroniclers. “Morga evidently reproduces here the account of the missionaries then who saw devils everywhere, for it is incredible that the author had attended the heathen ceremonies of the Indios. All the histories written by the religious before and after Morga, until almost our days, abound in stories of devils, miracles, apparitions, etc., these forming the bulk of the voluminous histories of the Philippines…”

[9] Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. W.H. Scott, Ateneo de Manila University Press. 1994. p.234

[10] Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. POTET, Jean-Paul G. Lulu.com, 2018. p. 212

[11] The Rizal Blumentritt Correspondence, Volume I, 1886-1889. National Historical Institute, 1992. p. 70

[12] T.H. Pardo de Tavera was a Filipino physician and writer during the 19th and 20th centuries; he wrote during the Propaganda Movement.

[13] DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS, Ferdinand Blumentritt, The Aswang Project, 2001, p. 75

[14] Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano, 1969, Centro Escolar University Research and Development Center, p.8

[15] The Philippines at the Spanish Contact, F. Landa Jocano, 1975, MCS Enterprises, Inc.

[16] The Rizal-Blumentritt Correspondence, Part 1. José Rizal National Centennial Commission, 1961. Page 35

ART BY: Ark O. Parojinog

ALSO READ: The TAGALOGS Origin Myths: Bathala The Creator

Pre-Colonial RELIGION, CULTURE & SOCIETY of the TAGALOGS

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.