|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

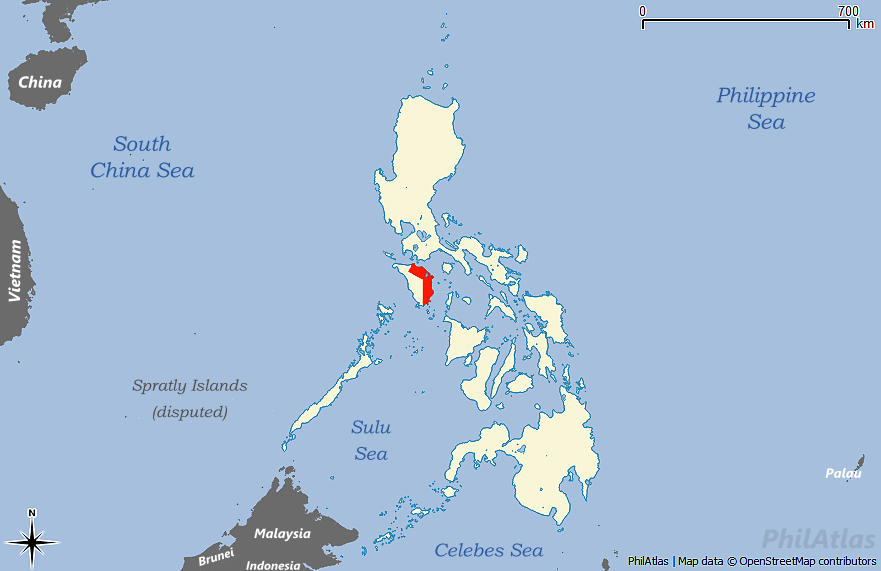

The Tagalog people are one of the largest ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, numbering around 30 million. They are native to the Metro Manila and Calabarzon regions of southern Luzon, and comprise the majority in the provinces of Bulacan, Bataan, Nueva Ecija and Aurora in Central Luzon and in the islands of Marinduque and Mindoro in Mimaropa.

I’ll start this with a bit of important history. The mountain dwelling Mangyan people are known as the original inhabitants of Mindoro. When the Spanish arrived at Mindoro in 1570, they found a rich, recently Islamized coastal population holding the trading center of the archipelago. There were mentions of mountain populations which were likely the Mangyan, pushed inland by arriving settlers. With the establishment of Spanish Manila, the newly Christianized population of Mindoro was in constant conflict with ‘Moros.’ This led to a steady depopulation of the island. After the American arrival, the Public Land Law of 1904 encouraged settlement and homesteading on Mindoro. Most of the arrivals were from the Tagalog areas of Luzon, as well as many people from Panay. Tagalog became the prominent coastal language.

I have been sitting on the “Origin of the Rainbow” myth from Oriental Mindoro for several years. Tagalog Mythology poses many problems for the researcher or reconstructionist. The Tagalog regions, along with many Visayan regions, were among the first to be colonized upon the arrival of the Spanish. This leaves a very small window of documentation to piece together what the religion of the early Tagalogs actually looked like. In my last article, I showed the likelihood of Tagalog areas holding varied beliefs from one another – highlighted by the Santo-Tomas, Laguna pantheon from Felipe Pardo’s paper of 1688.

Researchers have often focused solely on the early Spanish documentation and often combine those Tagalog beliefs regardless of which region they were documented in. When one reads through the Spanish accounts in the Blair and Robertson “The Philippine Islands,” it would appear that the Tagalog religion did not change much. Unfortunately, this is due to the Spanish plagiarizing each other’s work. I feel that the Pardo Paper (excluded from the B&R volumes) showcases that there wasn’t one single Tagalog religion, just as there was no single Visayan religion, Manobo religion, or even Bicolano religion. It is possible that the popular Tagalog pantheon was practiced in the most populated areas where townships were established by the Spanish, but undoubtedly changed from region to region, displaying certain overlaps. These nuances can only be examined now through their evolutions, or by seeking out new documentation. One such examination may be had from the “Origin of the Rainbow” myth from Mindoro, which likely arrived with settlers to Mindoro at the beginning of the twentieth century.

In the following myth, documented in 1971, you will learn that Bathala had seven children mainly named after the celestial bodies and elements they represent. This differs from the information documented by F. Landa Jocano in his 1969 work “Outline of Philippine Mythology” where Bathala had three demigoddess daughters (Tala, Mayari, Hanan), and is entirely different from the minimal entries found in The Boxer Codex (c. 1590) and Plasencia’s Customs of the Tagalogs (c. 1589), among others. As I mentioned in my previous article, these ‘newer’ myths only give us a snapshot of the beliefs at the time of documentation. I understand how one might wish to exclude it from a religious reconstruction. I would argue that, despite Christianization, these stories survived and evolved over 400 years and give an incredible insight as to how indigenous and syncretized cultural tradition survived. These can often be found in what has been relegated to the realms of superstition and folklore.

There are 20 or so generations of Filipinos that deserve considerable praise for holding, sharing, evolving, and retelling these myths, epics and stories through colonial history. Not to mention the indigenous groups that came out of colonialism relatively intact, such as the mountain tribes of Luzon, Panay, Mindoro, Mindanao, and the indigenous peoples of Palawan.

In 2010 there were approximately 1,846, 757 people in the Philippines practicing indigenous religions exclusively – or syncretized with Islam and Christianity. These are living traditions that survived colonialism, yet a mostly imaginary invention of the babaylan is celebrated over the living babaylan and other indigenous shamans who still practice today. There is a plethora of valid reasons for this which I may look at in a future article.

Please enjoy the following myth and the associated Tagalog deities from Mindoro. 🙂

Bathala’s Children and other Deities Documented in Oriental Mindoro c. 1971

Bathala, supreme being in the heavens.

Tala, the morning star. Bathala’s daughter.

Liwayway, the dawn. Bathala’s daughter.

Tag-ani, the goddess of harvest. Bathala’s daughter.

Bighari, who was the goddess of flowers, loved to play among the flowers in the garden. Bathala’s daughter.

Kidlat, the lightning. Bathala’s son.

Hangin, the wind. Bathala’s son.

Araw, the sun. Bathala’s son.

Panginoon, the messenger of Bathala.

The Origin of the Rainbow (Tagalog)

A long, long time ago people prayed to Bathala and offered him gifts for they believed that he was God and the source of all graces.

One day Bathala thought of making a journey to the earth. He said to himself, “My people on earth have been very good to me. I would like to make them happy.”

Bathala commanded his messenger to call all his children in heaven. He wanted to see them before he went down to earth. First, the daughters came. They were such lovely maidens and among them were Tala, the morning star; Liwayway, the dawn and Tag-ani, the goddess of harvest. A loud noise and a blinding blaze accompanied the arrival of his sons Kidlat, the lightning; Hangin, the wind; and Araw, the sun. All the other sons came hurrying. They knew that when Bathala called, they should lose no time in coming.

ART BY @rincs.art

Bathala’s children were now all seated. Looking at one empty seat, Bathala said, “Bighari is not here again. Did my messenger tell her about this meeting?”

“Panginoon, I looked for Bighari but she was nowhere to be found,” said the messenger who looked very tired.

“Perhaps, she is among the flowers in some distant land on earth,” someone whispered. The others exchanged glances, for they knew that Bighari, who was the goddess of flowers, loved to play among the flowers in the garden.

Bathala was indeed very angry. “This will not do,” he strongly said. “How many times has she been late. I will not allow tardiness among my children. If Bighari prefers to be with her children, she can stay with them forever.”

ART BY @rincs.art

His children were afraid. They looked at one another in silence. After a brief pause, Bathala continued, “From now on, Bighari will remain forever wherever she is right now to live there alone.” Bathala’s children were saddened by those angry words. They loved their beautiful and kind sister Bighari. But no one could protest Bathala’s decision to exile Bighari from his heavenly kingdom.

At that very moment, Bighari was having a delightful time among the flowers in a faraway garden on earth. When it was time for her to return to her heavenly home, she could not find her way out. She was worried about her father. When the messenger came to tell her of Bathala’s anger, she sobbed and said, “I’m not sorry to lose my place in the heavenly kingdom. I grieve because I have offended my father.” The messenger was very sorry for her, but there was nothing he could do.

ART BY @rincs.art

So the flower garden on earth became Bighari’s home. The flowers bloomed all the more and gave forth beautiful colors never seen before. Everybody around was so delighted. The people who were living nearby saw that the garden grew lovelier everyday. Soon Bighari had many friends. They came to see the flowers and admire their beauty. The people loved Bighari more and more. One day somebody suggested: “Let us build a bower in Bighari’s garden so that we can see the beautiful flowers even from afar.” So the people built a bower. It was high and it arched over the entrance of the garden. Soon the arch was decked all over with blossoms of red, yellow, pink, orange, blue, and white.

Thereafter, whenever the goddess of flowers goes on a journey we can see the lovely many-colored arch in the sky—the rainbow.

SOURCE: Emilia N. Abrigo, “Oriental Mindoro Folktales: An Analysis” ( M.A. Thesis , PWU , 1971 ), pp. 61-64.

ORIGIN OF THE RAINBOW FROM: EUGENIO, Damiana, Philippine Folk Literature: The Myths, UP press (2001) pgs. 252-253

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: SCHULT, Volker, The Genesis of Lowland Filipino Society in Mindoro, Philippine Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (First Quarter 1991), pp. 92-103

FOLLOW THE ARTIST:

WEB rincs.art

INSTAGRAM https://www.instagram.com/rincs.art/

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.