THE BONTOC (or Bontok) ethnolinguistic group can be found in the central and eastern portions of Mountain Province, in the Philippines. Although some Bontocs of Natonin and Paracelis identify themselves as Balangaos, Gaddangs or Kalingas, the term “Bontoc” is used by linguists and anthropologists to distinguish speakers of the Bontoc language from neighboring ethnolinguistic groups. They formerly practiced head-hunting and had distinctive body tattoos.

The pre-Christian Bontoc belief system centers on a hierarchy of spirits, the highest being a supreme deity called Intutungcho, whose son, Lumawig, descended from the sky (chayya), to marry a Bontoc girl. Lumawig taught the Bontoc their arts and skills, including irrigation of their land. The Bontoc also believe in the anito, spirits of the dead, who are omnipresent and must be constantly consoled. Anyone can invoke the anito, but a seer (insup-ok) intercedes when someone is sick through evil spirits.

The indigenous religion of the Bontoc has been preserved for centuries. The Bontoc believe in a unique pantheon of deities, of which the supreme deity is the cultural hero, Lumawig, son of Kabunian. There are many sacred sites associated with Lumawig and a variety of Bontoc deities.

Bontok Deities

Intutungcho (Kabunian): the supreme deity living above; also referred to as Kabunian; father of Lumawig and two other sons.

Lumawig: also referred as the supreme deity and the second son of Kabunian; an epic hero who taught the Bontoc their five core values for an egalitarian society The Bontoc hero Lumawig instituted their ator, a political institution identified with a ceremonial place adorned with headhunting skulls. Lumawig also gave the Bontoc their irrigation skills, taboos, rituals, and ceremonies after he descended from the sky and married a Bontoc girl. Each ator has a council of elders, called ingtugtukon, who are experts in custom laws (adat). Decisions are by consensus. (read the Legend of Lumawig here).

Chal-chal: the deity of the sun whose son’s head was cut off by Kabigat; aided the culture hero Lumawig in finding a spouse.

Kabigat: the deity of the moon who cut of the head of Chal-chal’s son; her action is the origin of headhunting.

Son of Chal-chal: his head was cut off by Kabigat; revived by Chal-chal, who bear no ill will against Kabigat.

Ob-Obanan: a deity whose white hair is inhabited by insects, ants, centipedes, and all the vermins that bother mankind; punished a man for his rudeness by giving him a basket filled with all the insects and reptiles in the world.

Chacha’: the deity of warriors.

Ked-Yem: the deity of blacksmiths who cut off the heads of the two sons of Chacha’ because they were destroying his work; was later challenged by Chacha’, which eventually led into a pechen pact to stop the fighting.

Two Sons of Chacha’: beheaded by Ked-Yem, because they were destroying his work.

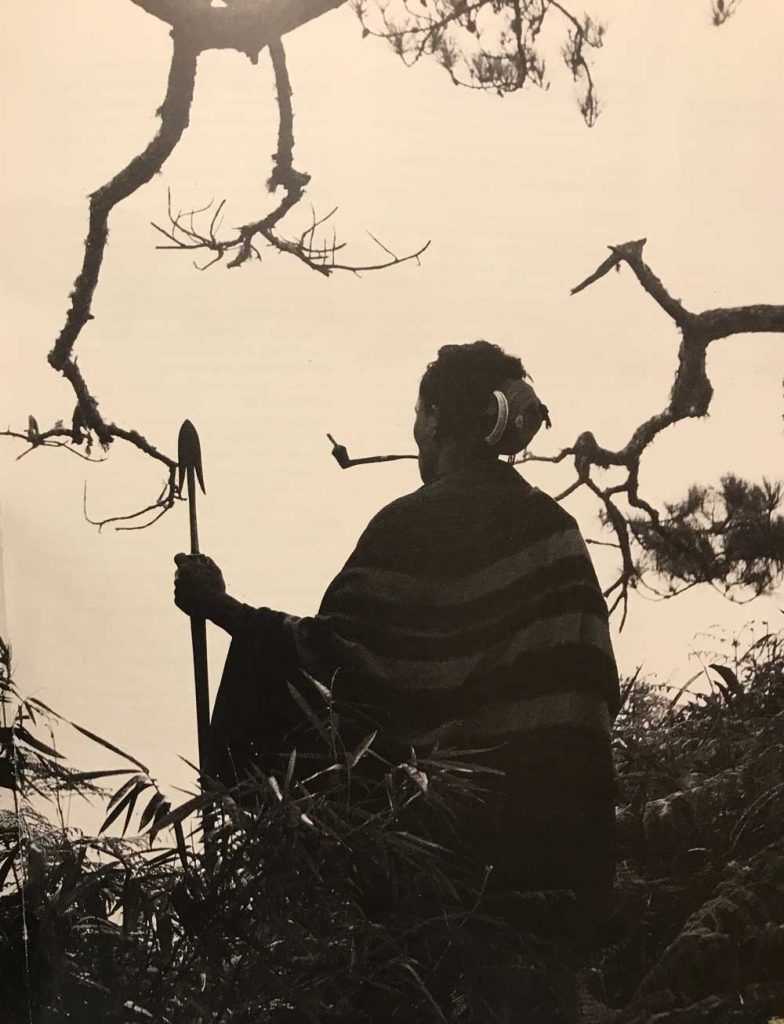

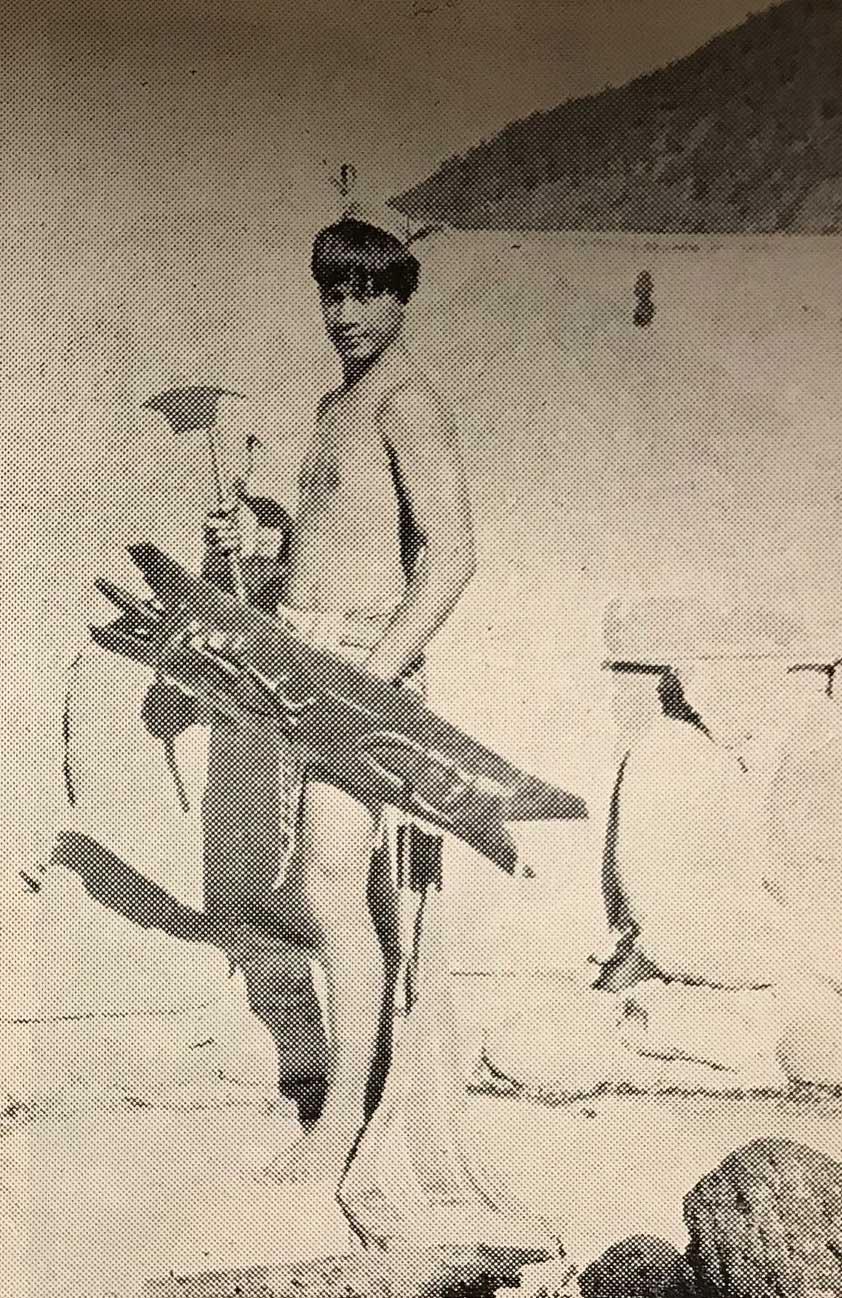

PHOTO: Eduardo Masferre

The Origin of Headhunting

The Moon, a woman called “Kabigat,” was one day making a large copper cooking pot. The copper was soft and plastic like potter’s clay. Kabigat held the heavy sagging pot on her knees and leaned the hardened rim against her naked breasts. As she squatted there—turning, patting, shaping the huge vessel—a son of the man Chal-chal, the Sun, came to watch her. This is what he saw: The Moon dipped her paddle, called pip-i, in the water, and rubbed it dripping over a smooth, rounded stone, an agate with ribbons of colors wound about in it. Then she stretched one long arm inside the pot as far as she could. “Tub, tub, tub,” said the ribbons of colors as Kabigat pounded up against the molten copper with the stone in her extended hand. “Slip, slip, slip,” quickly answered pip-i, because the Moon was spanking back the many little rounded domes which the stone bulged forth on the outer surface of the vessel. Thus the huge bowl grew larger, more symmetrical, and smooth.

Suddenly the Moon looked up and saw the boy intently watching the swelling pot and the rapid playing of the paddle. Instantly the Moon struck him, cutting off his head.

Chal-chal was not there. He did not see it, but he knew Kabigat cut off his son’s head by striking with her pip-i.

He hastened to the spot, picked the lad up, and put his head where it belonged—and the boy was alive.

Then the Sun said to the Moon:

“See, because you cut off my son’s head, the people of the Earth are cutting off each other’s heads, and will do so hereafter.”

“And it is so,” the storyteller continue, “they do cut off each other’s head.”

SOURCES: Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). “1 The Bontoks”. Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Cawed, Carmencita (1972). The Culture of the Bontoc Igorot. Manila: MCS Enterprises.

Almendral, E. C. (1972). Talubin Folklore, Bontoc, Mountain Province. Baguio City: Lyceum of Baguio.

Albert E. Jenks, The Bontoc Igorot, (Manila: Bureau of Public Printing, 1905)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.