Wherever you are in the Philippines, you probably won’t find a house that doesn’t have a special place for holy figurines: wooden replicas of benevolent saints, the holy family and even guardian angels. Having these figures is said to bless the house with good fortunes, good health and protection. This is part of how Filipinos express their faith as Catholics. Although some will debate that this is “idolatry”, others venerate these figures like they are not just an image, but God himself.

Though this practice appears to be acquired from the Spaniards, some of the oldest ethnic groups in the Philippines that were least affected by colonization also exhibit images in their homes to ensure a good life – and they have been doing this since before the Spaniards brought Catholicism.

Bu’lul, the Ancestor’s Link to the New Generation

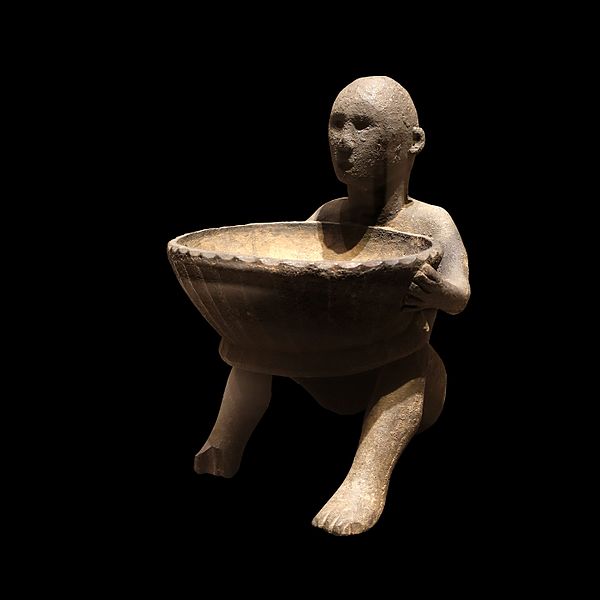

The Ifugao people are one of the few ethnic groups in the Philippines who successfully resisted major influences from the Spaniards. Although they are now acclimatizing with the modern day life; their indigenous beliefs and practices are still alive. One of these is the making and utilization of Bu’lul figures. Often made from strong Narra wood (or occasionally in stone), Bu’lul come in a variety of sizes, but all retain a plain appearance of an anthropomorphic guise. According to the belief of the Ifugao, Bu’lul house the spirits of their ancestors, which makes these figures not just a mere image or representation but rather a vessel of divine essence.

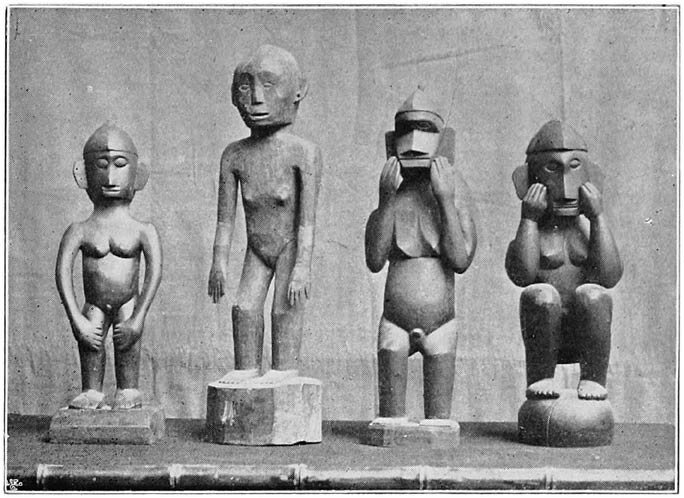

Bu’lul are usually made in pairs: one male and female. Although they have no apparent distinction in style, male and female Bu’lul are differentiated by their sizes (male is larger than female) or with an additional design (male Bul’lul are depicted with their genitals). Sometimes, they also put clothing and accessories on them during rituals: bahag (loin cloth) for the male Bu’lul and tapis (waist cloth) for the female Bu’lul. There is also meaning behind their position: standing Bu’lul are made to guard the granary or rice storage. while the ones who sit or squat have a role in good harvests and healing. In addition to this, standing Bu’lul are known to be made in the northern part of Ifugao and the sitting ones are done in the southern part.

Creating a Bu’lul figure is not as simple as other crafts. A ritual conducted made by a Mumbaki (their shaman/priest) allows their ancestral spirit to endow the wooden figures with their blessing and sacred essence. Bu’lul are given great care, for it is believed they can cause sickness and misfortunes if not appeased immediately.

When and How: The Origin of Bu’lul

There are two tales that narrate how Bu’lul become an object of worship to the Ifugao. One is the curious story of Namtogan, an ancient Filipino god depicted with a disability. Based on the tale, Namtogan visited the Ifugao province and fell in love with a mortal woman from a village called Ahin. The people of this village treated Namtogan very well because of his condition and in return Namtogan made their harvest bountiful.

The villagers however became so immersed in their affluent life that they forgot about Namtogan. This angered the god and he cursed Ahin before he threw himself in the river. The moment Namtogan left the village, plagues and pestilences scourged the land of his wife. Realizing that Namtogan was the one who caused their good fortune, the villagers searched for the angry god. Fortunately they found him in a Balete tree near Ibulao River.

However, Namtogan refused to return to the village no matter how hard they persuaded. Out of sympathy for the people who formerly took care of him, he instructed them to create his image out of wood. He also taught them rituals and ceremonies that they should conduct during various periods of each year for their harvest. Thus the practice of making Bu’lul was started.

The second story involves another deity called Humidhid from Daiya. This story elaborates on why Bu’lul found its place in the rice granary. One day Humidhid was disturbed by a crying Narra tree that begged for someone to carve it into a Bu’lul. The god Humidhid made several Bu’lul and place them in his house. In time the Bu’lul becomes unruly and too voracious for food, prompting Humidhid to throw them in the river.

Years had passed and a daughter of Humidhid, called Bugan, encountered a Bu’lul in the river as she searched for her missing lime container. As it turned out, Bugan fell in love with the Bu’lul who found her precious lime container. The couple visited Humidhid who would later advise his grandchild that whenever they visit the mortal realm, they must carve a Bu’lul out of a Narra tree for protection. The grandchild of the deity did what they were instructed to do but later experienced the same problem: the Bu’lul demanded too much food.

Therefore, Humidhid instructed that they must build a separate house for the Bu’lul. This place eventually became the granary.

Bringer of Good Harvest

Bu’lul are often associated with agriculture as they are the ones who protect the rice granary and bless the land for a bountiful of harvest. For every rice granary an Ifugao owns, they place a pair of Bu’lul to protect it. But sometimes one Bu’lul is sufficient enough. Sometimes when they are from a noble family, they place as many Bu’lul as they like. During rituals, the male Bu’lul is placed on the right side and on the left is the female.

As the mumbaki conducts the ritual, blood from pigs or chicken are smeared on the Bu’lul figures as an offering to the ancestral spirits that reside in them. This often leads to a change in the surface color and explains why some have a more darkened shade.

Economy, Culture and Religion

One of the challenges facing Bu’lul culture today is the sudden rise in the marketability of these statues – especially to the tourists visiting the Cordillera region. Many have a perception that these wooden figures are nothing but souvenirs. Sometimes our fellow Filipinos will only recognize Bu’lul as mere decorations. It is a sad truth that only a few will try to trace its importance to the natives of Ifugao and how it nurtured their culture as well as their untainted spirituality.

Though it is quite interesting that Bu’lul are perceived as an exotic sculpture, one should not forget its real value is as an object of veneration and sacredness.

Another challenge is our ingrained aversion to pagan beliefs. If we look beyond the influence from foreign culture, perhaps we can understand that the Bu’lul is not about religion or idol worshiping alone; it is more embedded in our true cultural roots as an animistic nation. We should be thankful that after all this time, the Ifugao managed to preserve and protect something that should remind us of our identity.

Sources:

Peatfield, Andeas, The Changing Social Biography of the Bulul of Ifugao (2015)

Lapniten, Karlston, Indigenous Paraplegic Divinity: The Story of Namtogan (2018), Published at Philippine Daily Inquirer on May 29, 2018

Ocampo, Ambeth, ‘Bulul’ and Filipino Identity (2016) Published at Philippine Daily Inquirer

Acda, Rico, Antiquity: Bulul: A Mythical Piece of Ifugao Sculpture (taken from Artes De Las Filipinas)

ALSO READ: IFUGAO DIVINITIES: Philippine Mythology & Beliefs

Currently collecting books (fiction and non-fiction) involving Philippine mythology and folklore. His favorite lower mythological creature is the Bakunawa because he too is curious what the moon or sun taste like.