A Cyclops, in Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, was a member of a primordial race of giants, each with a single eye in the center of his forehead. The word “cyclops” literally means “round-eyed or “circle-eyed”.

In a famous episode of Homer’s Odyssey, the hero Odysseus encounters the cyclops Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon and Thoosa, who lives with his fellow cyclopes in a distant country.

So where the heck did the Philippine cyclops, Bungisngis, come from? Tracing the origins of folkloric creatures in Philippine mythology is a long and complicated process. For those interested, I have written 3 articles which outline the basics of the migrations, immigrations and religious influences which must be considered. Using this information makes tracing the origins of the Bungisngis a much simpler task.

SEE: ANIMISM | Understanding Philippine Mythology (Part 1 of 3)

Bungisngis: What we know

Lucky for us, Dr. Maximo Ramos has already done most of the legwork that needs to be accomplished within the Philippines. This is outlined in his book “The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology”.

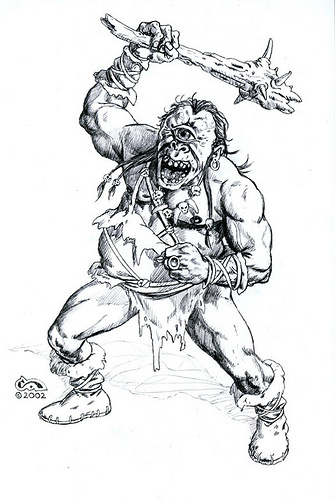

Ramos explains, in a Batangas tale, the giant Bungisngis is described as “a large strong man who is always laughing.” His name is said to be derived from the Tagalog word ngisi (‘to show the teeth’). He is also said to have “an upper lip so large that when it is thrown back, it completely covers [his] face.” His strength is indicated by his reportedly seizing a carabao by the horns and throwing it “knee-deep into the earth.”

Bungisngis lived in a forest where three animal friends went hunting one day. The Bungisngis appears to have had a human appetite which is commensurable with its size. In the Batangas tale, Bungisngis was led by his hearing to where a carabao was frying meat in the woods. He then demanded the meat from the latter, saying, “Well, friend, I see you have prepared food for me.” He did violence to the carabao and then ate the meat.

The entire folktale, “The Three Friends,–The Monkey, the Dog, and the Carabao”, is printed below.

Bungisngis: Tracing the Origins

Tracing the origin of the Bungisngis was actually quite easy, thanks to a similar being existing in the Ibalong Epic. The Ibálong, also known as Handiong, or Handyong is a 60-stanza fragment of a Bikol full-length folk epic of Bikol region of Philippines, based on the Indian Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharta from the era of Indianized 7th century kingdom of Srivijaya and earlier period. In the Ibalong, the cyclopean giant is known as “Buring“, while in the Hindu epic it is known as “Kabandha”. Similarly, Biag ni Lam-ang ( “The Life of Lam-ang”) is an epic poem of the Ilocano people from the Ilocos region of the Philippines influenced by the same Indian Hindu epics. Bicol and Bantangas were part of the Indianized areas of the Philippines. While the Bungisngis is not part of a Batangas epic, it does play a central role in the folk story, “The Three Friends,–The Monkey, the Dog, and the Carabao.“

We are almost certain that much of the Indianized influence came via migration and trade through Borneo and other areas of the Malay Peninsula. Recent DNA studies show that there may have even been Indian settlers in the Philippines before the arrival of the Spanish. In the case of the Bungisngis folktale, there are striking similarities to stories from Borneo. This similarity was documented in “Filipino Popular Tales Collected and Edited with Comparative Notes” By Dean S. Fansler.

“For a Borneo story of a “Deer, Pig, and Plandok (Mouse-Deer)”. In this tale, it is the clever plandok who alone is able to outwit the giant. In the latter story there are seven animals,–carabao, ox, dog, stag, horse, mouse-deer, and barking-deer. The carabao and horse in turn try in vain to guard fish from the gergasi (a mythical giant who carries a spear over his shoulder). The plandok takes his turn now, after his two companions have been badly mishandled, and tricks the giant into letting himself be bound and pushed into a well, because the “sky is falling.” There he is killed by the other animals when they return.”

Bungisngis Folktale: The Three Friends,–The Monkey, the Dog, and the Carabao.

From: Filipino Popular Tales Collected and Edited with Comparative Notes By Dean S. Fansler (1921)

Once there lived three friends,–a monkey, a dog, and a carabao. They were getting tired of city life, so they decided to go to the country to hunt. They took along with them rice, meat, and some kitchen utensils.

The first day the carabao was left at home to cook the food, so that his two companions might have something to eat when they returned from the hunt. After the monkey and the dog had departed, the carabao began to fry the meat. Unfortunately the noise of the frying was heard by the Buñgisñgis in the forest. Seeing this chance to fill his stomach, the Buñgisñgis went up to the carabao, and said, “Well, friend, I see that you have prepared food for me.”

For an answer, the carabao made a furious attack on him. The Buñgisñgis was angered by the carabao’s lack of hospitality, and, seizing him by the horn, threw him knee-deep into the earth. Then the Buñgisñgis ate up all the food and disappeared.

When the monkey and the dog came home, they saw that everything was in disorder, and found their friend sunk knee-deep in the ground. The carabao informed them that a big strong man had come and beaten him in a fight. The three then cooked their food. The Buñgisñgis saw them cooking, but he did not dare attack all three of them at once, for in union there is strength.

The next day the dog was left behind as cook. As soon as the food was ready, the Buñgisñgis came and spoke to him in the same way he had spoken to the carabao. The dog began to snarl; and the Buñgisñgis, taking offence, threw him down. The dog could not cry to his companions for help; for, if he did, the Buñgisñgis would certainly kill him. So he retired to a corner of the room and watched his unwelcome guest eat all of the food. Soon after the Buñgisñgis’s departure, the monkey and the carabao returned. They were angry to learn that the Buñgisñgis had been there again.

The next day the monkey was cook; but, before cooking, he made a pitfall in front of the stove. After putting away enough food for his companions and himself, he put the rice on the stove. When the Buñgisñgis came, the monkey said very politely, “Sir, you have come just in time. The food is ready, and I hope you’ll compliment me by accepting it.”

The Buñgisñgis gladly accepted the offer, and, after sitting down in a chair, began to devour the food. The monkey took hold of a leg of the chair, gave a jerk, and sent his guest tumbling into the pit. He then filled the pit with earth, so that the Buñgisñgis was buried with no solemnity.

When the monkey’s companions arrived, they asked about the Buñgisñgis. At first the monkey was not inclined to tell them what had happened; but, on being urged and urged by them, he finally said that the Buñgisñgis was buried “there in front of the stove.” His foolish companions, curious, began to dig up the grave. Unfortunately the Buñgisñgis was still alive. He jumped out, and killed the dog and lamed the carabao; but the monkey climbed up a tree, and so escaped.

One day while the monkey was wandering in the forest, he saw a beehive on top of a vine.

“Now I’ll certainly kill you,” said some one coming towards the monkey.

Turning around, the monkey saw the Buñgisñgis. “Spare me,” he said, “and I will give up my place to you. The king has appointed me to ring each hour of the day that bell up there,” pointing to the top of the vine.

“All right! I accept the position,” said the Buñgisñgis. “Stay here while I find out what time it is,” said the monkey. The monkey had been gone a long time, and the Buñgisñgis, becoming impatient, pulled the vine. The bees immediately buzzed about him, and punished him for his curiosity.

Maddened with pain, the Buñgisñgis went in search of the monkey, and found him playing with a boa-constrictor. “You villain! I’ll not hear any excuses from you. You shall certainly die,” he said.

“Don’t kill me, and I will give you this belt which the king has given me,” pleaded the monkey.

Now, the Buñgisñgis was pleased with the beautiful colors of the belt, and wanted to possess it: so he said to the monkey, “Put the belt around me, then, and we shall be friends.”

The monkey placed the boa-constrictor around the body of the Buñgisñgis. Then he pinched the boa, which soon made an end of his enemy.

A Side Note on the Cyclops

It has been theorized that the origin of the cyclops may be attributed to the finding of a “dwarf elephant” skull. Dwarf Elephants also roamed the Luzon and Panay area during the Pleistocene Era, so the cyclops may not be entirely a foreign concept.

ALSO READ: CYCLOPEAN GIANTS: Ang-ngalo and Aran, the Creators | Ilocos, Philippines

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.