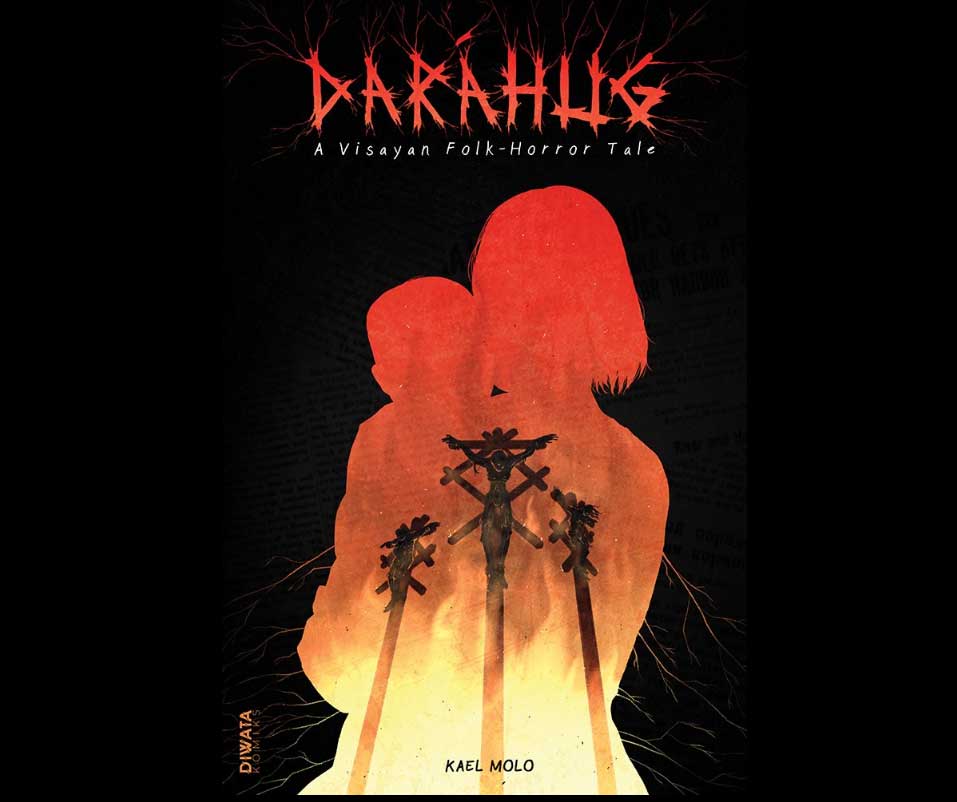

For the past week, I have been re-writing the opening sentences to share my thoughts on Darahug: A Visayan Folk-Horror Tale. I am unsure how I can capture the layered story that is presented without spoiling it for those who have yet to open the cover.

I first became aware of Darahug’s author and artist, Kael Molo, in 2015 while he was releasing character art for his web-based Visayan Mythology comic, Agla. He was the first creator I had come across that delved deep into existing myths, the deities, and how those beliefs would integrate themselves into the lives of precolonial village folk, culminating into the origin of ‘pintado’ warriors. C’est très en vogue en ce moment, so it is no surprise that Kael moved on to blaze a trail in Philippine folk-horror.

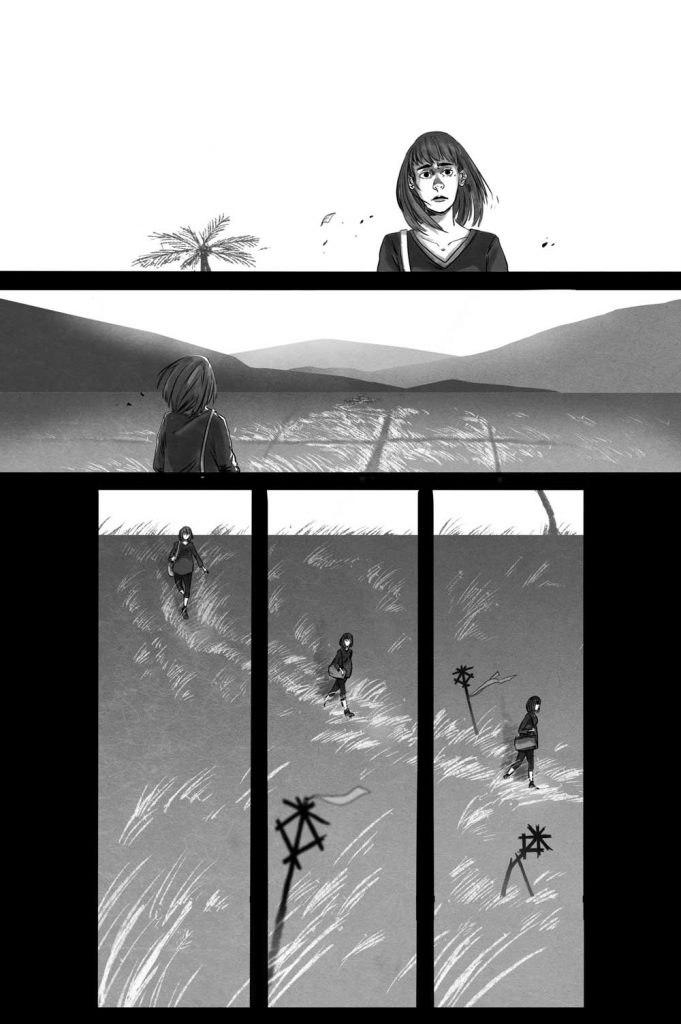

I don’t want to give away the story of Darahug, but it reveals itself in many complicated layers. I think it is safe to share that the story begins with a young pregnant woman riding on a rural bus. After seeing she is the last passenger and the driver explains they have reached the final stop, she mentions her destination as Santa Maria. This clearly strikes fear into the local driver who is glad to let her out after giving walking directions for the remainder of her journey to the far-flung village. As she passes through the Visayan country landscape, we begin to see unnerving wooden structures, which could remind some of the weather-horns seen in some areas of Sagada. Spirit structures are very common and are part of the living practices of the indigenous groups in the Philippines. Their unknown nature could be disconcerting for those who happen across them – or perhaps I’m projecting. We can assume she is going to see the Mananabang (Visayan midwife) as alluded to in the comic’s opening text. What follows is a superb exploration of folk-horror that hits every mark for devotees of the genre – “isolation, religion, the power of nature, and the potential darkness of rural landscapes.”

Molo never shies from expressing the dangerous aspects of old religion, juxtaposed with the failings of the new. Darahug exemplifies the reality that folk religion in the Philippines holds a potential cure for the shortcomings of society, policy, and equality. While Darahug is a Waray-Waray term meaning “the physical or mental injury inflicted by a supernatural entity on a human victim, “ it is society’s flaws that are most injurious in this story.

I have spent the last week ruminating on the themes of Darahug and how those social issues have affected the people I care about in the Philippines. It brought up instances where I have seen hospitals, government, and social services break laws or make them up to avoid the scrutiny of church or state, or to skim from funding meant for the well being of the more vulnerable population. There is no recourse for the poor, other than…perhaps…folk practices.

For those who follow The Aswang Project, you’ll know that I am a huge fan of the writer, Yvette Tan. She often writes about the folkloric beings of the archipelago, but it is the human condition that creates the horror. Kael has also accomplished this in Darahug, and it is a welcomed relief from the common themes we are seeing repeated in many modern Philippine komiks. This isn’t to take away from those efforts (I love them as much as the next person), but sometimes it’s nice to shake things up and avoid fatigue.

You are never left wondering what a character’s emotion is in Darahug. Kael Molo’s art fits perfectly into the diverse art styles of modern comics that don’t always follow a specific set of inspiration. That said, I can’t help but feel the latter part of Darahug will satisfy even the most affectionate fan of the Japanese horror mangaka, Junji Ito.

Following the main komik is a prequel short story by Kael Molo. It takes place in the late 80’s at the end of martial law, and centers on a US army unit tasked by the UN to provide relief to distant Visayan villages. While I don’t necessarily feel this story was needed, it was great to see Darahug’s folklore explored from an entirely different perspective. Essentially, we read how idealistic American bravado – thinking they know what is best for the Philippines and their people – is brought down by the folk beliefs that awaited them. Again, the limit of meaning to the stories in Darahug are only impeded by how deeply you contemplate the themes, and how openly you view the social and political issues facing the country. It holds the potential of becoming profoundly personal in a time where we are all ruminating on current events and opinionated stands.

Diwata Komiks isn’t messing around with the printing quality they present for their titles. The paper is thick, the colours rich (*noting Darahug is B&W), and the covers are meant to last. Darahug comes with a silk touch cover which feels wonderfully unnatural after exploring the content. This is a brave title to present and Kael Molo, along with Diwata Komiks, should be lauded for its release. Highly recommended!

*Please be advised this title is rated MA 18+ for EXPLICIT CONTENT. For mature readers only. Reader discretion is advised.

Darahug may be ordered in the US through Diwata Komiks. https://www.diwatakomiks.com/store

For thos in the Philippines, the US release of Darahug can be found through Comic Odyssey. Message them for pre-ordering and stock information.

Keep an eye open for the re-release of Kael Molo’s “Bloodpaint Chronicles: Agla.”

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.