A DIWATA is most popularly known in modern times as a nature spirit or a ‘fairy’ that is often a steward over a certain mountain or piece of land. In ancient Filipino culture, the diwata or anito was the dominant concept in the various religions throughout the archipelago. The anito concept was prominent in Luzon, while the diwata prevailed in the Visayas and Mindanao.

Diwata (Sanskrit origin; Deva “divine”, devata “celestial beings”) is the name that the various groups of the southern archipelago give to their spirits and deities. The following are known:

1. Amongst the early Visayans they had Diwata, similar to the anitos of the Tagalogs. For the Tagalogs, each anito had a particular office whose blessings and favor they implore when they go to the battlefield. Anitos shielded them from diseases. There were also “anitos of the house, whose favor they implored whenever an infant was born, and when it was suckled and the breast offered to it.” [1] Another anito whom Fr. Juan de Placensia, O.S.F. identifies as Dian Masalanta is known to be the “patron of lovers and generations.” [2] Alzina chronicled the most famous and well-attended communal rituals, called pagtigma-an. This was performed in every community in Leyte and Samar by the bailanes or daetan for their diwatas (the souls of their deceased ancestors). [3] In some published versions of F. Landa Jocano’s translated recordings of the Hinilawod epic of Panay, Nagmalitong Yawa Sinagmaling Diwata was described as a beautiful deity who was married to Saragnayan (the keeper of light) and was desired by one of the epic heroes, Labaw Donggon.

2. The Batak of the island of Palawan give the name Diwata to minor spirits. While this author was visiting the Batak of Palawan, it was believed a diwata was in the river that runs through the village and was making the people ill. The people had been advised by their Babaylan (healer) to stay out of the river between twelve noon and two in the afternoon.

3. The Tagbanuwas, another indigenous people of Palawan, called the spirits and invisible beings diwatas. “The diwatas control the rain, and they are believed to be the creator of the world and of human beings. They live where the tree trunks hold up Langit (“an infinitely high canopy”), which is the visible celestial region.” [4]

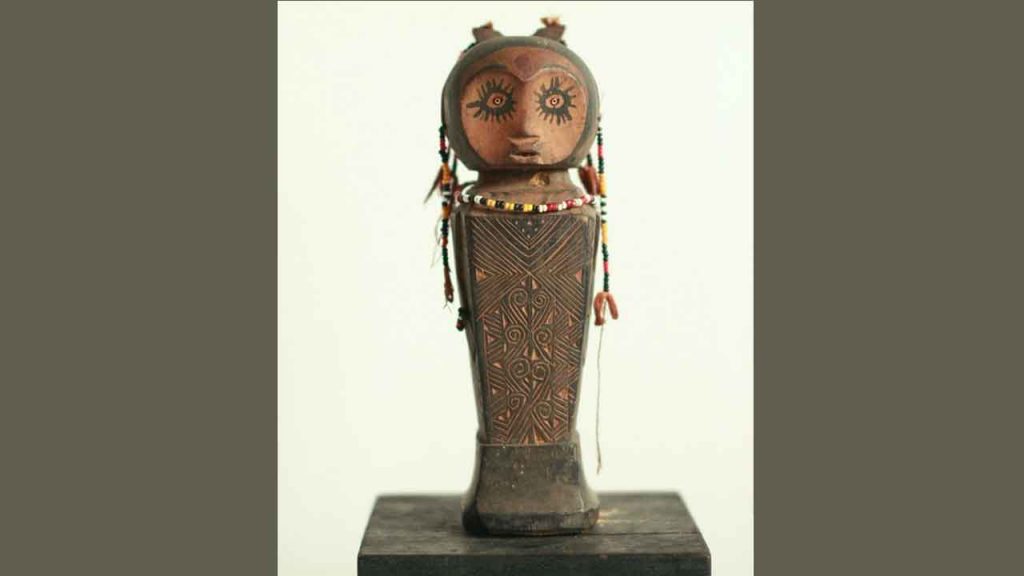

4. The Mandayas (Mindanao) call the idols that represented their ancestors Diwata or Manaog.”A good spirit who is besought for aid against the machinations of evil beings. The people of Mayo claim that they do not now, nor have they at any time made images of their gods, but in the vicinity of Cateel Maxey has seen wooden images called manaog, which were said to represent Diwata on earth. According to his account “the ballyan dances for three consecutive nights before the manaog, invoking his aid and also holding conversation with the spirits. This is invariably done while the others are asleep.” He further states that with the aid of Diwata the ballyan is able to foretell the future by the reading of palms. “If she should fail to read the future the first time, she dances for one night before the manaog and the following day is able to read it clearly, the Diwata having revealed the hidden meaning to her during the night conference.” [5]

PHOTO: USC Museum

5. The Bagobos (Mindanao) know, more or less, a Diwata. However it is assumed that they do not give this name just to a singular spirit. “Diwata. A class of numerous spirits who serve Eugpamolak Manobo – first and greatest of the spirits, and the creator of all that is.” [6]

6. Also the Manobos (Mindanao) have a spirit called Diwata. “The bailán is a man or woman who has become an object of special predilection to one or more of those supernatural friendly beings known among the Manóbos as diuáta.” [7]

7. The Subanos (Mindanao) relate only in a vague meaning of the Diwata, and dark idea of god, of whom they are very afraid of. It is assumed that the Subanos know not only one, but many diwatas.

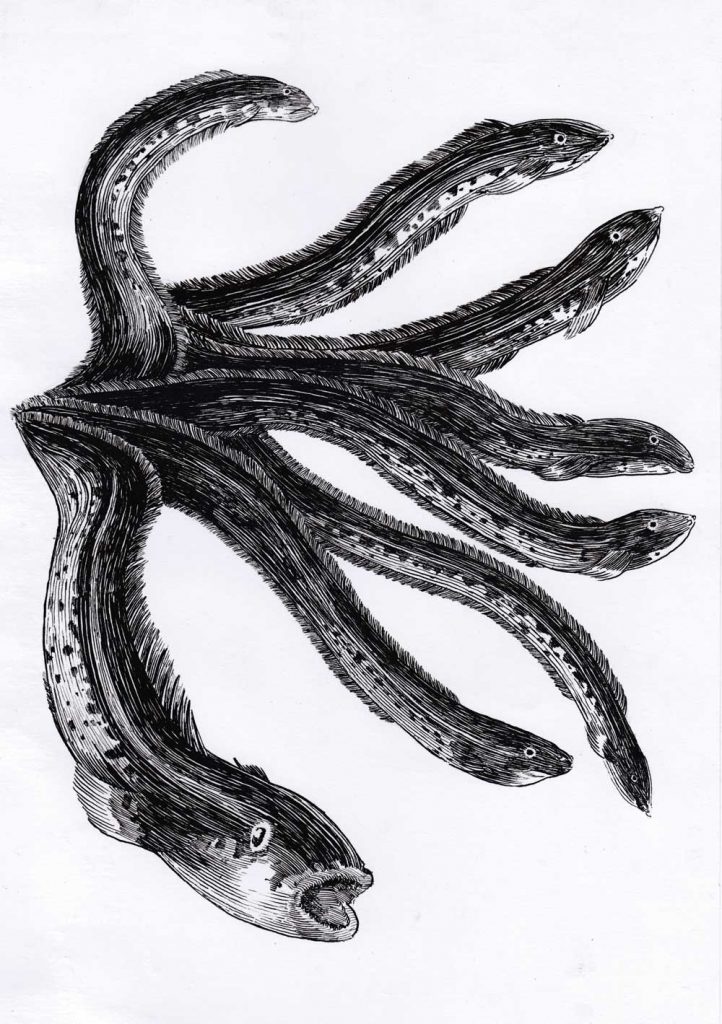

8. The Tirurayes call a superstitious fish that has eight heads and lives in Ombligo or in the middle of the river, a Diwata. It is assumed that this is not the only monster that the Tirurayes call Diwata. Other spirits and mythical beings are also called this name. [8]

9. The Manguindinao Moros call the idols and gods of the infidels, their neighbors, Diwata.

Until very recently, the term Diwata was not used in the island of Luzón.

Additional Notes.— The term Diwata is derived from the Sanskrit term Deva or devata. In Hinduism, Devas are celestial beings associated with various aspects of the cosmos. Devatas often occur in many Buddhist Jatakas and Hindu epics such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Many Philippine epics are based on the Ramayana.

The filipino Diwata has the same origins in term of language derivation. The Javanese has spirits called Dewata or Djuwata. The Dayaks, in western Borneo, know their supreme god under the name Djewata or Djebata; they call a category of spirits that are in the inferior world or in hell, Djata (contraction of djebata). The Macasares and Bugis of the island of Celebes call a category of guardian angels, Rewata or Dewata. The Bolaang-Mongondouers on the Sulawesi island call their supreme god, Ompu-duata (ompu = grandfather; Duata = Dewata). The Bantiks (Natives of the Minahasa or of the boreal peninsula of Sulawesi) call their angels Mobuduata. The Bataks of Sumatra call their idols Debata idup, these represent the sialon or spirits of their most distant ancestors. [9]

Diwata Legends in Philippine Mythology

Maria Sinukuan – the diwata (or nature spirit) associated with Mount Arayat in Pampanga, Philippines.

Maria Cacao – the diwata or mountain goddess associated with Mount Lantoy in Argao, Cebu, Philippines.

Maria Makiling – a diwata or lambana (fairy or forest nymph) associated with Mount Makiling in Laguna, Philippines. She is the most widely known diwata in Philippine Mythology, and was also invoked to stop deluge, storms and earthquakes

You’ll notice they all carry the same name of “Maria”. One might assume that this means these Diwatas are a fairly recent invention – and you’d be right about Maria Sinukuan and Maria Cacao, but not for the reasons you think. However, the name “Mariang Makiling” is the Tagalog contraction of “Maria ng Makiling” (Maria of Makiling). The term is a hispanized evolution of an alternate name for the Diwata, “Dayang Makiling” – “dayang” being an austronesian word meaning “princess” or “noble lady”.

Although “Maria” was certainly given her “Christian name” during the Spanish occupation, the etymology of “Maria” is also very interesting. During the Roman Empire, the name “Maria” was used as a feminine form of the Roman name Marius. It became popular with the spread of Christianity as a Latinized form of the Hebrew name of Jesus’ mother Mary (Miriam in Hebrew or Maryam in Aramaic). The meaning of the Semitic-rooted name is uncertain, but it may originally be an Egyptian name, probably derived from mry “beloved” or mr “love” (“eminent lady” or “beloved lady”).

As for the word “Makiling“, it has been noted that the mountain rises from Laguna de Bay “to a rugged top and breaks into irregular hills southward, and thus appears to be leaning or uneven.” The Tagalog word for ‘leaning’ or ‘uneven’ is “Makiling.” This corresponds with the common belief that the profile of the mountain resembles that of a reclining woman, from certain angles.

So who were these guardians of the land?

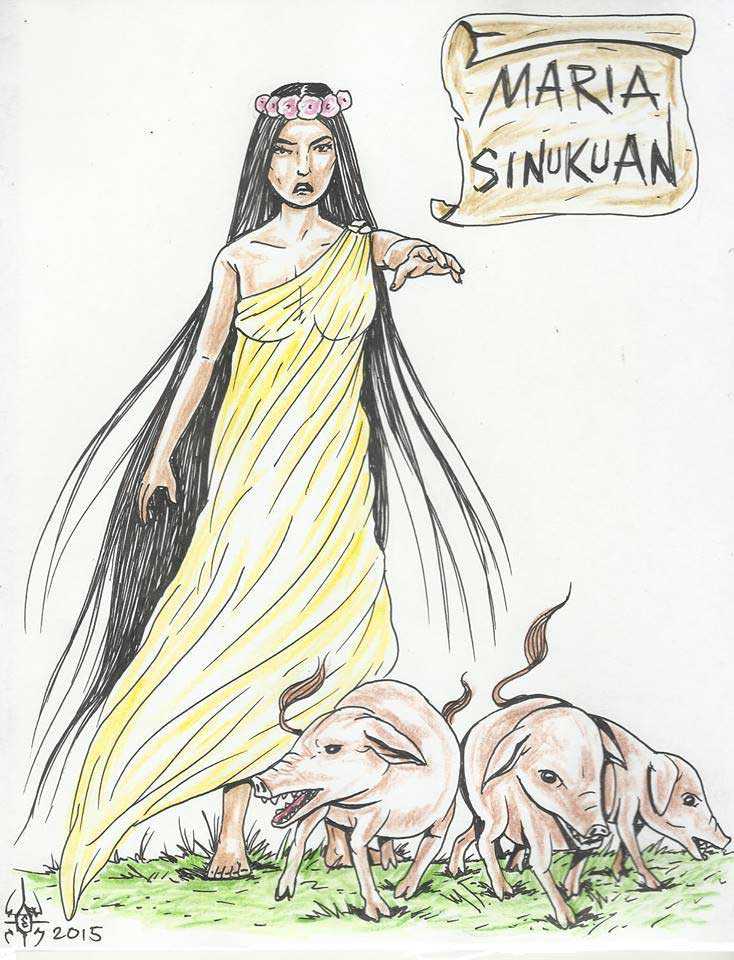

The Story of Maria Sinukuan

Once upon a time, they say that Mt. Arayat abounded in all kinds of fruit trees. Aside from the fruit trees, it is said that animals of all kinds once roamed this mountain. The strange thing about this fruit trees and animals is that the fruit trees bore exceptionally big fruits all the year round and the animals was no other than Mariang Sinukuan. These fruit trees and animals, Mariang Sinukuan used to distribute to the poor. Needy families often woke up on the morning to see at their doorsteps fruits and animals for their needs. They knew it was Mariang Sinukuan who left this foods while they were sleeping. How grateful the people were to be graced by the enchanted lady. And to show their gratitude and respect they never tried to go to her hide-out in the mountain. The people considered her home as a sacred place.

But such was not always the case. There came a time when the people were no longer satisfied with what the enchanted lady left at their doorsteps. They wanted to get more.

One day, some young men decided to go up Mt. Arayat. They wanted to get more of Mariang Sinukuan’s fruits and animals. They started for the mountain early at dawn. They reached the base of the mountain at sunrise. Guavas bigger than their fists dangled from the guava trees. Pomegranate branches almost reached to the ground because of the many and big fruits they bore. Ripe mangoes were just within one’s reach. Fowls of every kind were plentiful. Pigs, goats and other animals roamed around. The young men were still viewing this wonder of nature when from nowhere came Mariang Sinukuan. They were dazzled by her brilliance. They could not find any words to say to her. It was Mariang Sinukuan who first spoke to them.

” Welcome to my home, young men. Help yourself to the fruits. Eat as much as you can but I’m warning you not to take anything home without my knowledge.” With this, the enchanted lady departed.

After recovering from their amazement, the young men started to pick up fruits. They ate and ate until they could not eat any more.

“Let us pick some more fruits. I want to fill this sack which I brought,” said one.

“No, let’s not do that. Let’s go home now,” said another. “I’m scared.”

” Why be scared? Did we not come to get more fruits and animals?”

” But the lady warned us not to take anything home without her knowledge.”

“Oh, come on. She won’t know we took home fruits and animals. They’re so plentiful, she won’t know the difference.”

And so the young men started to fill their sacks with as many fruits and animals as they could get hold of. Then they started for home. As they were about to begin their descent they felt their sacks becoming heavier. They didn’t mind this, but they had not gone ten steps farther when they felt that their load was pulling them down. Putting the sacks down, how surprised the young men were to find that the fruits and animals had become big stones. They remembered Mariang Sinukuan’s warning. The young men became terribly frightened. Leaving their sacks behind, they ran as fast as their feet could carry them. But before they reached the base of the mountain whom did they see blocking their way? It was Mariang Sinukuan who was very angry.

“You ungrateful wretches! I help you in times of need. But how do you repay me. You are not satisfied with what I leave you at your doorsteps. And now you even try to steal my things! Because of your greediness I’m going to turn you all into a swine.” With the wave of her wand, Mariang Sinukuan changed the young men into swine.

This was not the last time that people tried to get hold of Mariang Sinukuan’s fruits and animals. Again and again they tried to steal them. At last, fed up with the people’s greediness, Mariang Sinukuan stopped leaving food at their doorsteps. She caused the fruit trees and animals in the mountain to disappear. She no longer showed herself to the people for she was disgusted with their greediness.

Birth of the Maria Sinukuan Legend: In what has been documented of ancient Kapampangan folklore, and in the research gathered by Kapampangan students of Henry Otley Beyer in the 1940s, Mount Arayat is only known as the abode of Apung/Aring Sinukuan (sun god of war and death, taught the early inhabitants the industry of metallurgy, wood cutting, rice culture and even waging war). Although early beginning of this legend were documented in the travel diary of Italian adventurer Gemelli Careri, 1696.

Documented legend says Mount Arayat is the home of the god/sorcerer named Sinukuan/Sinukwan or Sucu, which could mean “the end” or “he who others have surrendered to.” The mountain was said to have been located in the swamp to its south but relocated because of the evil ways of those who lived there, in addition to which, the people of the swamp were made to suffer numerous misfortunes. Sinukuan is believed to be able to transform and do as he pleases at will, his only real rival being Namalyari of Mount Pinatubo. The waterfalls at Ayala in Magalang, Pampanga is said to be his bathing quarters, and it is often visited by tourists and natives alike. Sinukuan is said to live at the White rock, a Lava dome possibly formed by the last eruption, where its glimmering properties were most likely to have inspired the legend. Contrary to reality, the mountain is believed to be several mountains merging at the center including the tallest two peaks.

In other legends, Sinukuan is said to have bested Makiling of southern Luzon almost effortlessly, unlike his arch rival Namalyari. Sinukuan is believed to have daughters who come down only during time of grace and are disguised as humans, Sinukuan himself can be disguised as human. The day he comes back is believed to either be when he responds to the attack of Namalyari on Mount Pinatubo’s 1991 eruption or when the time to call his servants upon the end of the world has come. In other tales, Makiling (as a goddess instead of her modern incarnation of a diwata) is the love object of Sinukuan.

The Story of Maria Cacao

The basic form of the legend is that whenever rains flood the river that comes from Mount Lantoy, or a bridge is broken, this is a sign that Maria Cacao and her husband Mangao have either travelled down the river in their golden ship so that they can export their crops, or travelled up the river on their way back. She is supposed to live inside a cave in the mountain and the Cacao plants outside it are supposed to be her plantation. While the story is obviously mythical in nature, it is cited as evidence of how long the production of tableya, has been going on in the area. Tableya is Cebuano for round, unsweetened chocolate tablets made from cacao beans. It is a crucial ingredient in the Filipino delicacies sikwate (hot chocolate) and champorado.

Birth of the Maria Cacao Legend: Boy, you guys aren’t going to like me. Maria Cacao is probably older than Maria Sinukuan, but couldn’t have gotten her name until sometime in the late 1600s when cacao was first introduced to the Philippines (The first recorded crop was in 1670). Some suggest that the story of Mangao already existed and that Maria Cacao was adopted into the folk story. In a paper by Koki Seki, “Rethinking Maria Cacao: Legend-making in the Visayan Context”, it is stated that the legend of Maria Cacao may have more to do with migratory experiences of the local people, rather than anything directly related to the name. “The ubiquitous legend of Maria Cacao is given a specific form and expression in the course of migration experiences of the narrators. In turn, it enables the narrators to structure and imagine their reality in a particular way; for instance, the intensification and activation of their image of homeland and identity.” In the case of Maria Cacao, the belief in diwatas may have still been prevalent in the region where the story was created.

Maria Makiling

Similar to Maria Sinukuan of Pampanga’s Mount Arayat and Maria Cacao on Cebu’s Mount Lantoy, Maria Makiling is the guardian spirit of Mount Makiling, responsible for protecting its bounty and thus, is also a benefactor for the townspeople who depend on the mountain’s resources. In addition to being a guardian of the mountain, some legends also identify Laguna de Bay – and the fish caught from it – as part of her domain.

Legends of Maria Makiling

Because stories about Maria Makiling were part of oral tradition long before they were documented, there are numerous versions of the Maria Makiling legend. Some of these are not stories per se, but superstitions.

Superstitions about Maria Makiling

One superstition is that every so often, men would disappear into the forests of the mountain. It is said that Makiling has fallen in love with that particular man, and has taken him to her house to be her husband, there to spend his days in matrimonial bliss. Another superstition says that one can go into the forests and pick and eat any fruits one might like, but never carry any of them home. In doing so, one runs the risk of angering Maria Makiling. One would get lost, and be beset by insect stings and thorn pricks. The only solution is to throw away the fruit, and then to reverse one’s clothing as evidence to Maria that one is no longer carrying any of her fruit.

Turning Ginger into gold

Perhaps the most common “full” story is that of Maria turning ginger into gold to help one villager or the other. In these stories, Maria is said to live in a place known to the villagers, and interacts with them regularly. The villager in question is often either a mother seeking a cure for her ill child, or a husband seeking a cure for his wife.

The wise Maria recognizes the symptoms as signs not of disease, but of hunger brought about by extreme poverty. She gives the villager some ginger, which, by the time the villager gets home, has magically turned to gold

In versions where the villager is going home to his wife, he unwisely throws some of the ginger away because it had become too heavy to carry.

In some versions, the villagers love her all the more for her act of kindness.

In most, however, greedy villagers break into Maria’s garden to see if her other plants were really gold. Distressed by the villager’s greed, Maria runs away up the mountain, her pristine white clothing soon becoming indistinguishable from the white clouds that play amongst the trees on the upper parts of the mountains.

Spurned Lover

In many other stories, Makiling is characterized as a spurned lover.

In one story, she fell in love with a hunter who had wandered into her kingdom. Soon the two became lovers, with the hunter coming up the mountain every day. They promised to love each other forever. When Maria discovered that he had met, fell in love with, and married a mortal woman, she was deeply hurt. Realizing that she could not trust townspeople because she was so different from them, and that they were just using her, she became angry and refused to give fruits to the trees, let animals and birds roam the forests for hunters to catch, and let fish abound in the lake. People seldom saw her, and those times when she could be seen were often only during pale moonlit nights.

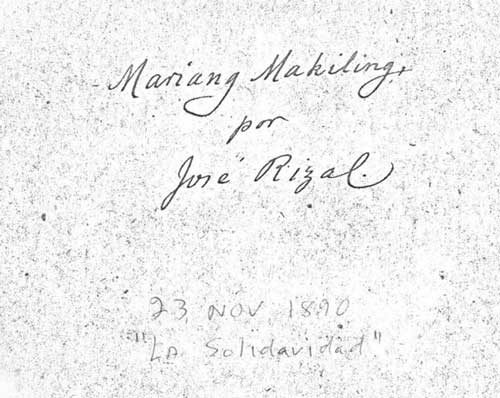

In another version of the story, told by the Philippines’ National Hero, Jose Rizal, Maria falls in love with a farmer, whom she then watches over. This leads the townspeople say he is endowed with a charm, or mutya, as it is called, that protected him and his from harm. The young man was good at heart and simple in spirit, but also quiet and secretive. In particular, he would not say much of his frequent visits into the wood of Maria Makiling. But then war came to the land, and army officers came recruiting unmarried young men. The man entered an arranged marriage so that he could stay safely in the village. A few days before his marriage, he visits Maria one last time. “I would that you were consecrated to me,” she said sadly, “but you need an earthly love, and you do not have enough faith in me besides. I could have protected you and your family.” After saying this, she disappeared. Maria Makiling was never seen by the peasants again, nor was her humble hut ever rediscovered.

CLICK HERE for a PDF of Jose Rizal’s story, “Mariang Makiling”

The Three Suitors

Michelle Lanuza tells another version of the story, set during the later part of the Spanish occupation:

Maria was sought for and wooed by many suitors, three of whom were the Captain Lara, a Spanish soldier; Joselito, a Spanish mestizo studying in Manila; and Juan who was but a common farmer. Despite his lowly status, Juan was chosen by Maria Makiling.

Spurned, Joselito and Captain Lara conspired to frame Juan for setting fire to the cuartel of the Spanish. Juan was shot as the enemy of the Spaniards. Before he died, he cried Maria’s name out loud.

The diwata quickly came down from her mountain while Captain Lara and Joselito fled to Manila in fear of Maria’s wrath. When she learned what happened, she cursed the two, along with all other men who cannot accept failure in love.

Soon, the curse took effect. Joselito suddenly contracted an incurable illness. The revolutionary Filipinos killed Captain Lara.

“From then on,” Lanuza concludes, “Maria never let herself be seen by the people again. Every time somebody gets lost on the mountain, they remember the curse of the diwata. Yet they also remember the great love of Maria Makiling.”

Mount Makiling still abounds with superstitions and stories concerning Makiling. When people get lost on the mountain, the disappearances are still attributed to the diwata or to spirits who follow her.

Philippine Microsatellite Diwata-1

Diwata-1 also known as PHL-Microsat-1 is a Philippine microsatellite launched to the International Space Station (ISS) on March 23, 2016, and was deployed into orbit from the ISS on April 27, 2016. It was the first Philippine microsatellite and the first satellite built and designed by Filipinos. It was followed by Diwata-2, launched in 2018.

A team of nine Filipino engineers from the DOST-Advanced Science and Technology Institute (ASTI) and the University of the Philippines, dubbed the “Magnificent 9”, were responsible for the production of Diwata-1 and collaborated with scientists and engineers from the two Japanese universities.

The satellite was named after a type of divine being from Philippine mythology, the diwata.

ART: Enrico delos Reyes from Creatures Of Darkness (Philippines) and Charisse ‘Dadis’ Melliza.

Sources:

[1] Loarca in Blair and Robertson, Vol. V, p. 173.

[2] BLAIR AND ROBERTSON, VOL. VII, P. 189

[3] The Munoz text of Alzina’s Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas (1668) Part I, Book 4, trans. Paul Lietz (Chicago: University of Chicago, Philippine Studies Project, Department of Anthropology), p. 229.

[4] FOX, ROBERT B. Religion and Society Among the Tagbanuas of Palawan Island, Philippines. Monograph No. 9, National Museum: Manila, 1982.

[5] The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao, Fay-Cooper Cole, FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY PUBLICATION 170, ANTHROPOLOGICAL SERIES VOL. XII, No. 2.1913

[6] Ibid

[7] THE MANÓBOS OF MINDANÁO, John M. Garvan, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES, 1931

[8] La Religion Antigua de los Filipinos, Isabelo de Los Reyes

[9] DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS, Ferdinand Blumentritt [1895], translated and republished by The Aswang Project, 2021

Addiotional Sources:

Eugenio, Damiana (2002), Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends, UP Press

Maria Cacao: Ang Diwata ng Cebu (Maria Cacao: The Fairy of Cebu) Rene O. Villanueva

Municipality of Arayat (1997) Arayat Town Fiesta ’97 Souvenir Program for Filipino

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.