by Francisco R. Demetrio, S.J.

Rural peoples of the Philippines believe in the existence of, as well as the influence exercised on human lives by superhuman beings called engkantos. The belief found in Luzon is also quite common in the Bisayas and in Mindanao. What is noteworthy is that this belief seems to have endured for at least four centuries: Povedano (16th century), Alzina (17th) and Pavon (19th)1 allude to the belief in engkantos. Nor is the belief dead today. In one year, I was able to collect 87 long and short narratives from persons who either had been befriended or kidnapped by engkantos, or from people very closely associated with the victims, and are therefore presumed to know about the case.

Three Levels of Interpretation

The phenomenon of engkanto belief, from the viewpoint of cultural anthropology, may be studied on at least three levels: sociologically, the function it fills for the people in whose midst this belief prevails (e.g., as social control, as was pointed out by Richard W. Lieban in his article “The Dangerous Engkantos: Illness and Social Control in a Philippine Community,” American Anthropologist, Vol. 64, April, 1962, 306-312); or psychologically, by suggesting the etiology of engkanto belief, as Jaime Bulatao has done for the poltergeists in his article in Philippine Studies, Vol. 16 (January, 1968), 178-188, or by summoning the aid of C. G. Jung’s symbol of individuation to explain the reputed vision or visits of engkantos;2 or phenomenologically, after the manner of the students of comparative religion of the school of Gerardus van der Leeuw,3 Brede Kristensen4 and Mircea Eliade.5 By a close analysis of the complex elements which make up the phenomenon of engkanto belief, and comparing these with very similar if not identical phenomena in other cultures, we shall perhaps be able to understand better the meaning and intentionality of the strange behavior of peoples under the influence of this belief. Since I am neither sociologist nor psychologist, I shall limit my exposition to the third level: the religious phenomenological interpretation of engkanto belief.

The Method

First, the themes that make up the pattern of engkanto beliefs should be gathered together under three headings. Second, from the studies of the historians of religion on the phenomenon of the initiation of the shamans in other cultures,6 a tentative interpretation of the most peculiar themes that underlie every manifestation of the engkanto that we know, namely, the disappearance of the victim and the seizure of madness usually accompanied by a show of extraordinary strength, should be established.

The Themes of the Engkanto Belief

The Theme of Mystery

Although engkantos are said to have male and female sexes; although there are children, young people, adults and aged among them; although they get sick and even die; yet they are a class of beings quite removed, different from ordinary humans.

Their very name suggests this. Encantado from which engkanto seems to be derived is the preterite perfect of the Spanish verb encantar, and it means “bewitched,” “spell-bound,” or “enchanted.” Though the native names may not especially stress their mysteriousness: tumao, (Povedano MS, 1578), tiaw (Cagayan de Oro, Gingoog City, Misamis Oriental, 1966), meno (Iligan City, 1967), panulay (Siquijor, 1967), tagbanua (Talakag, Bukidnon, 1967), or Ti Mamanua, or Tumatima (Kalbugao, Kisolon, Bukidnon, 1967), still further characterization given them by the Bisayans, does. The engkantos are said to be “dill ingon nato,” “dili ta parehas,” (“people not like or similar us”).

Their dwelling places to the naked eye are mere boulders, large rocks or holes in the ground, or mounds on the earth, or trees like the balete. But to their human friends who are empowered to see them, these are magnificent palaces and mansions. Their food is first class, but contains no salt.

Though beautiful and fairskinned, they are said to be romantically attracted to a brown-skinned girl or boy. Although spirits, they are said to indulge in dalliance with mortal beings.

Though known to dislike noises, they themselves are sometimes known to indulge in raucous noises while they are at feast, or when they punish a mortal for either refusing their love or for abandoning them.

They are whimsical and unpredictable; they play jokes on people, making them go astray in the forest at night, or transform themselves into the likenesses of mortal friends and relatives in order to dupe the object of their desire.

The Theme of Dreadfulness

Engkantos are sometimes associated with souls of dead ancestors, and are therefore objects of dread. People observe silence when they approach their reputed habitats: large rocks, large trees, secret caves or springs and fountains. Those whom they favor with their attention suffer tremendous dread and anguish; they disappear for a day or more, even for months, they suffer from delirium, and fits of madness. Engkantos are known to possess .power to inflict diseases: fevers, boils and other skin diseases, the result of their curse or buyag. Without one’s knowing it one brushes against them because they are unseen, and, bingo, they slap a person on the face, or crack a rift on his skull. They inject fear by the spectacular feats they do in order to punish whoever disregards their affections: stonethrowing, wrapping clothes around a post closed on both ends; appearing in huge balls of fire, causing things to move’, producing loud noises. And they are dreaded again because of their demonic character: unpredictable, amoral, capricious.

The Theme of Fascination

For all their mysteriousness and capriciousness, the engkantos to the Filipinos are fascinating beings. Whoever sees them reports of their beauty: fair-complexioned, golden-haired, blue-eyed, clean-cut features, perfectly chiselled faces. They exemplify the best of the Spaniards (in the past) and of the Americans (in the present). Their homes are splendid; their furniture regal. They own wharves inside large caves and ships plying from one ocean to another; they have chariots and Cadillacs. Men and women are allured by their beauty, their riches and their power. Besides, if they love a person they will make him rich and powerful. And they are generous. There are stories of mortals borrowing tablewares from engkantos for their fiestas and celebrations. Shamans and mananambal go out of their way into far and lonely caves, on Holy Thursday or Good Friday, in order to commune with the engkantos and to acquire power in disease-healing and in combatting evil spirits. Whenever the conversation turns toward the engkanto, even the most sophisticated lends a listening ear. So although people are afraid of them they still feel a certain deep-seated attraction or fascination for these creatures. The demonic character of the engkantos, their whimsicalness and capriciousness, their unpredictability, while injecting fear and awe at the same time, attract mortals who secretly wish they were the special attention of these strange, dreadful yet fascinating beings.

Engkanto and the Demonic

From the above we can perhaps conclude that the engkantos do partake of the nature of the sacred or the holy: mysterious, dreadful yet alluring. (Mysterium tremendum et fascinans — Rudolf Otto). The holy or sacred manifested in the engkanto is not however of the same kind as that of the object of contemplation and adoration of the mystics of the higher religion. For the object of mysticism is the holy under the aspect of divine. Altogether other, transcendent Truth, Beauty, Goodness. The aspect of the sacred which experience of the engkantos manifests seems to be demonic. It is compounded of the possibility for both good and evil; holy and profane. It does not conduce to repose and calm ending in adoration, but to agitation and excitement crowned with anxiety.

Comment

There is no doubt that many of these reports and the details that accompany them are folkloristic embroideries. A number of the elements used to recount an engkanto encounter are also found in stories about the souls and poltergeists: like the moving of chairs, the rattling of tablewares, the stoning, the wrapping of clothing around a post planted on the ground. The no-salt business is also found in stories of souls. We can therefore dismiss many of these as part of the paraphernalia for folk tale telling. But there are however, at least, two themes which can be singled out in this complex because they generally seem proper to this phenomenon. These are: 1) the motif of disappearance on the part of the victim of the engkanto and 2) the theme of madness. To understand these, the findings of the historians of religion will be worth leaning upon. Briefly, the scenario of imitation as described and explained by the historians shall be studied, and then perhaps a deeper understanding of the phenomena of loss and of madness in engkanto cases can develop.

Interpretation of These Facts in the Light of Comparative Religion

Philippine Religion at the time of Conquest

Before the coming of Christianity, the peoples of these lands already had some kind of religion. For no people however primitive is ever devoid of religion. This religion might have been animism. Like any other religion, this one was a complex of religious phenomena. It consisted of myths, legends, rituals and sacrifices, beliefs in high gods as well as low; noble concepts and practices as well as degenerate ones: worship and adoration as well as magic and control. But these religious phenomena supplied the early peoples of these lands what religion has always been meant to supply: satisfaction of their existential needs. These needs were both material needs and psychic needs: the longing for fuller life, for a deeper and more satisfying communion with one another, the desire to surpass the human condition, to break out of the bonds of space and time and to contact the deity. Religion gave them solace in their griefs, holding out to them the promise of salvation, of the continuity of the flame of life even after it has been lost in death. Through the shamans whom they called bailanas or daetan (Alzina. 213 ff.), the will of the gods was channelled to the community.’ These persons were the specialists of the sacred; they were held in high esteem by the people; they were the diviners, the healers, the prophets, the psychopomps, the performers of sacrifices. They played an important social role: they provided the psychic equilibrium for the community.

Value of Early Philippine Religion

From the vantage point of a more sophisticated and technologically advanced culture, this religion was inadequate. But even as it was, this religion served the needs of the community. One cannot fully agree with the early Christian chroniclers who claimed that the religion of the early Filipinos was altogether diabolical. What had served the needs of the people for long centuries before the advent of Christianity cannot, in fairness and truth, be called the work of the devil pure and simple. Danielou in his book Advent has a beautiful passage where, he says that missionaries coming to a new field are not really bringing God and Christ there for the first time. For the Word has always been in the world which He made. He is the light that enlightens every man coming into the world (John 1: 9). The transcendental order or salvation based on God’s universal will to save the entire human race allows us to believe that the missionary in his pagan field merely discovers or uncovers God and His Word hidden behind their works and lives to the people he is to evangelize. It is in the peoples’ mores and manners, beliefs and basic orientations to life and reality, further specified by their peculiar cultures and traditions, that the missionary is to uncover God and His Christ to them.

Early Philippine Shamanism

We have it on reliable sources that shortly after the coming of Christianity (Alzina, 1668), the call to the office of bailana or daetan (priestess) among the Bisayans began precisely with this madness, or tiaw which the candidate underwent. Alzina has interesting stories telling of just this fact. The future bailanas were wont to be lost for quite some time. They were said to be brought into the forest by the spirits. When finally found, they were seen sitting absent-mindedly among the high branches of trees, or seated under a tree, especially the balete. Sometimes, too, these people were found stark naked, with dishevelled hair, possessed with a strength beyond the ordinary. Invariably they appeared to have forgotten their former selves. A power which they were powerless to shake off had them under its total dominance. Only after these people had been cured of their initial illness, did they begin to function as bailanas. This function made them the specialists of the sacred in the community.

Shamanism among Siberians

The historians of religion inform us that among the Buryat in Siberia, the shamans were called to their office in much the same way. A person’s election to the office was always preceded by a change of behavior. This behavior parallels in many ways the behaviour of the people befriended by the engkantos — the Filipinos. I quote from Eliade;

The souls of the shaman ancestors of a family choose a young man among their descendants; he becomes absent-minded and moody, delights in solitude, has prophetic visions, and sometimes undergoes attacks that make him unconscious. During these times the Buryat believe, the young man’s soul is carried away by spirits; received into the palace of the gods, it is instructed by his shaman ancestors in the secret of the profession, the form and names of the gods, the worship and names of the spirits. It is only after this first initiation that the youth’s soul returns and resumes control of his body (Rites of Initiation, 88).

Shamanism and Madness

Eliade goes on to add that since the middle of the 19th century, this strange behavior of the future shaman has exercised the wits of scholars. Invariably, however, this strangeness of manner has been attributed to mental disorder (Myths, Dreams and Mysteries, 76 ff). Eliade disagrees. His reason being that shamans are not always, nor do they have to be, mental cases. For those among them who had been ill become shamans precisely because they had succeeded in becoming cured. To obtain the gift of shamanism presupposes precisely the solution of the psychic crisis brought on by the first symptoms of election or call. Yet it must be pointed out, Eliade insists that, if we must not equate shamanism with pathological phenomenon, it is also true that shamanism implies a crisis so deep that it sometimes borders on madness. And what might be the cause of this disturbance? Eliade locates it in the “agonizing news that he has been chosen by the gods or the spirits.” For to be thus elected is to be delivered over to the divine or demonic powers; hence, to realize that one is destined to imminent death. (We shall point out below the connection between the agony of election to shamanism and the tortures of initiation whereby one either becomes an adult member of a community or assumes the role of a priest or hero.)

Initiation as Death and New Birth

A young man who is circumcised and is thus introduced into the secrets of the adults of a clan is generally spoken of by the primitive as being “killed” by semi-divine or divine beings. A future shaman also sees himself either in vision or in dream being delivered to death. He sees himself dismembered by demons. He may see them cut off his head and his tongue, pull out his intestines, scrape the flesh from his bones in order to provide him with the intestines and flesh of the spirits. Thus he enters a new mode of existence.

In Central Asia, historians of religion tell us, the initiation of future shamans include a symbolic ascent into heaven or descent into the land of the dead. This symbolic journey either way, up or down, may be at the root of the reputed disappearance of those befriended by the engkantos. Some of these people are lost only in their minds, they become unconscious, fall into a coma or fainting fits where they remain breathless and in deep slumber for days. It is noted that in a number of cases they appear in their trances or comatose state as through

being hurried along on fast moving vehicles. They tell afterwards of having ridden on engkanto ships or cars. In other cases, the bodies of the engkanto victims are reported missing for a day. Banana stalks are discovered by the relatives inside the coffin or on the bed. In other cases, the person is lost for days, even months. In this case of disappearance, the actual loss of the body seems to be itself symbolic of the deeper and more inward loss of one’s soul as it journeys to the land of spirits.

Disappearance and Madness Equal Initiatory Death

But the full significance of the phenomenon of madness and of disappearance of engkanto victims may be explained and understood rightly only if viewed against the background of the philosophy or theology of initiation.

In an initiation, the initiate undergoes a symbolic dismemberment of his own body. The dismemberment of the body in turn is i but an outer symbol of the dislocation and fragmentation of his inner personality and this is but a symbol of a still more profound religious truth: the necessity of death and dissolution in order that one might arise to newness of life and a fuller integration of being. Certain important events in the course of life are analogous to a new awakening or entrance into a fuller life and existence. This necessitates a preceding death to an imperfect, less real life.

To be introduced into the full life of the community, or to be invested with the responsibility of guarding the psychic health of the community are two important modes of being and acting which demand a giving up of something less perfect and less real. This leaving behind of the former securities and warmth of accustomed and familiar ways of life is really an entrance into death. And the stakes concerned in either initiation or election are basic to life and to existence itself. Thus it is that in the philosophy of initiation, the initiate or the chosen one must reproduce within this individual, personal psychic experience, the condition of the total universal chaos before the act of creation. For it was at this instance in the pre-history of the cosmos that life and existence were then made possible. Chaos which preceded cosmos was pregnant with the promise of the wonderful universe of creation. In primitive theology, the time before Creation was the time when Chaos and Disorder were regnant. This phase in the pre-life of the universe was a period of large uncertainties, of latencies, of indefiniteness; when things and the forms of things existed only in promise or in seeds. It was only the magnificent powers of the gods which made the chaotic state of latencies and seeds, all milling together as in a vast cauldron, to take on definite direction and shape; it was the word of creation which separated the light from dark, the wet from the dry, the up from the under. Yet this state of Chaos and primordial Disorder although in many ways fearsome and full of anxiety for the outcome of creation, in a very real sense, was also fraught with the promise of new existences. For it was precisely because things were in complete disarray, reduced to the condition of pure possibilities, that order could come out of them, that things with definite shapes and forms could issue out of that amorphous mess under the call of the creative word, or action of the gods.

For primitive theory, Chaos and Promise of Creation are two sides of the same reality: Life. The very disorderliness of the seeds of things before creation, in the consciousness of primitive man, seems to necessitate the intervention of the creative action of the gods in order to bring the cosmos into being. That is why all over the world archaic peoples seem to have intuited the real value and meaning of every arising unto new existence or a mode of it: such as the assumption of the full life as an adult member of the community or the taking on of the office of shaman or bailan, as a symbolic return to the pre-cosmic state of the world. This symbolic return to the days immediately before creation, as it were, magically provokes the new rush of divine power such as what took place in the first days of creation.

Conclusion

In view of the foregoing, the writer submits the following. It is no more than a hypothesis. Further verification, however, is required to establish its validity. While on the one hand it is true that not all that glitters is gold, it is equally true on the other that where there is true gold, it does glitter. Not every case of reported engkanto phenomenon is authentic. There are fake “victims” of engkanto who aim at catching the attention of the public. Yet it cannot be denied that there are genuine engkanto cases. Where such cases happen, the person becomes a changed individual. Whereas before he was an easy-going, quite irresponsible, unthinking fellow, after his encounter with the engkanto he has become a serious-minded, well-behaved, and useful member of the community. His usefulness is usually seen in his ability to cure sickness as well as to help others who are victims of barang and other harmful machinations.

The call or election by the spirits of certain individuals in the community to become their shamans or mediums seems to be still given to some favored few today. In the olden days, before the coming of Christianity such a call was accepted by the person concerned, and perhaps also by the community. The future shaman had a perfectly acceptable role to play: to become a specialist in the sacred, to help keep the psychic health of the people evenly poised. But with the coming of Christianity, the call to shamanism was no longer countenanced as part of the way of living. There has come about a change of attitude towards such election. In fact to be called to the office of shaman has been equated with being in league with the devil. Perhaps this realization may even account for part of the fear that dogs the consciousness of the selected one. As we saw above, to become an object of the special attention of the spirits is already a terrifying thing: it is to be delivered to the realm of the divine or the demonic, it is to be delivered to imminent death. But the further realization that this call is against one’s religion is further reason for anxiety.

The election by the spirits is really intended, in archaic communities, for undergoing the experience of initiation so that one may come forth a new being, a new man, possessed with special powers. I submit that this proper end of the call has been blunted, and the person involved as well as those to whom he relates his experience have given this call a romantic twist. I submit that this sexual meaning given the engkanto case may be an interpretation of the experience; and that this interpretation has achieved cultural proportions. So that every time there happens an engkanto experience, it is always seen as a romantic involvement between the spirit and the mortal. I agree that there may be some religious motivation at work even here. But I also submit that this may be due to acculturation since the days of the Spaniards. For the engkantos were always seen as handsome people, in fact they were said to look like Spaniards. And in the experience of many indios, the Spaniards in actual life were interested in the native women, usually for the sake of sexual gratification. Thus it might very well have been that the engkantos since then have been putatively motivated whenever they approached a mortal being in order to invite him to become a shaman.

That the fearsome experience, the swooning, the queer behavior, the apparent obliviousness of the surrounding reality, even the extraordinary strength of the engkanto victim, and the disappearance of the soul (ecstacy) or the actual physical disappearance of the victim, are all part and parcel of the scenario of initiation to which these select few are introduced in order to prepare them for the new role they are to play in the community. And the special gifts and feats which they subsequently perform are symbolic of the interior change in their personality: their clairvoyance, their power of divination and prophecy, their power to heal, their power of transformation, of causing good or ill to others, their mastery over the extremes of cold or heat, their control of fire — all these are effects of the new powers acquired by their senses as a result of the initiation.

NOTES

1. Among the longer narratives, only 2 may be classified as folktale pure and simple; that is, as artistic creations whose sole purpose is to entertain, not to report anything as having actually happened. The narratives come from Northern Mindanao generally: 43 from Cagayan de Oro and from the area of Misamis Oriental, 29 from Camiguin, 5 from Bukidnon, 3 from Bohol, 2 from Davao, and 1 contribution respectively from Lanao del Sur, Basilan and Negros Occidental- I also made use of 89 folk beliefs from various places: 45 coming from Davao, 15 from Cagayan de Oro and environs, 8 from Camiguin, 7 from Bukidnon, 6 from Misamis Occidental,3 from Romblon, and 1 each from Dipolog, Leyte and San Pablo City.

There were altogether 60 informants who supplied me with 87 folk narratives about experiences with engkantos. 21 were males and 38 females. All except 2 (aged 15 and 17 respectively) were at least 20 and above. There were 14 at ages 20 and over; 9 at ages 30 and over; 8 at ages 40 and over; 14 at ages 50 and more; 4 at ages 60 and above, 4 at ages 70 and above. So the informants were generally quite mature.

Of the 21 males, 5 were school teachers, 4 farmers, 2 librarians, 2 students, 2 policemen, 1 priest (now Most Reverend Archbishop Teofilo Camomot), 1 provincial sheriff, 1 engineer, 1 laundryman. Of the 39 females, there were 25 housewives, 4 servants or maids, 2 seamstresses, 2 teachers, 1 telephone operator, 1 market vendor and 1 student. So the informants seem to make a good cross-section of the population as far as their professions go.

2. G. Jung, Symbols of Transformation, trails. R. F. C. Hull (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1962), 2 vols.

3. Gerardus van der Leeuw, Religion in Essence and Manifestation, trans J. E. Turner (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1963), 2 vols.

4. Brede Kristensen. The Meaning of Religion, trans. J. B. Carman Netherlands, the Hague; Martinus Nijhoff, 1960), pp. 532.

5. Mircea Eliade. Patterns in Comparative Religion, R. Ward (New York: Meridian Book, 1963), also his Myths, Dreams and Mysteries (London: Harvill Press, I960); and the other Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1965).

6. For a discussion on shamanism, cf. the following books of Mircea Eliade: Myths, Dreams and Mysteries.- The Encounter Between Contemporary Faiths and Archaic Realities, Philip Mairet (London-. Harvill Press, 1957); Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth, trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1965).

Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstacy, trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: Pantheon Books, 1964).

Also Rudolf Rahmann, “Shamanism and Related Phenomena in Northern and Middle India,” Anthropos, vol. 54 (Switzerland: International Review of Ethnology And Linquistics,, 1959), 681-760.

Richard W. Lieban, “Shamanism and Social Control in a Philippine City” Journal of the Folklore Institute, vol. II (1965), 43 ff.

Cebuano Sorcery.- Malign Magic in the Philippines (Berkely and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967).

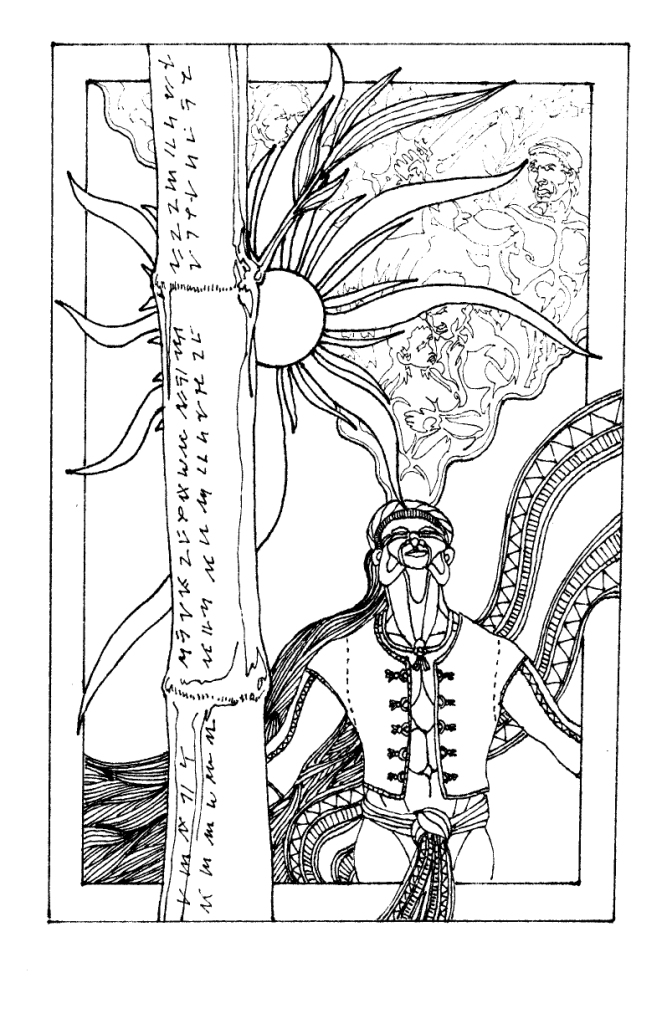

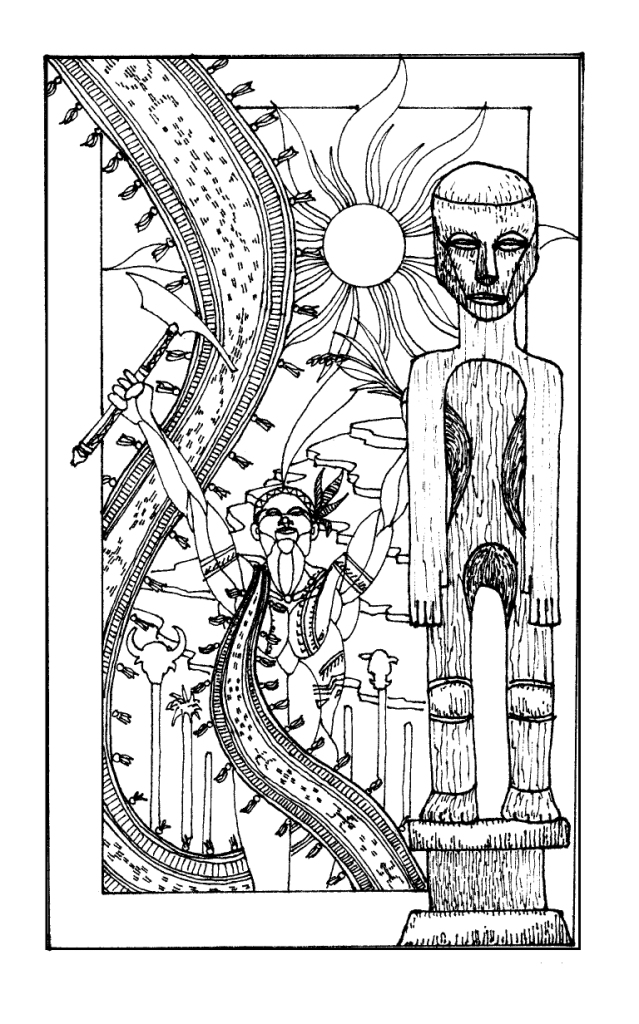

ART BY: Lakandiwa (John Paul ‘Lakan’ Olivares) via DeviantArt (https://www.deviantart.com/lakandiwa)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.