The Suludnon, also known as the Panay Bukidnon or Pan-ayanon, are a culturally indigenous Visayan group of people who reside in the Capiz-Lambunao mountainous area and the Antique-Iloilo mountain area of Panay in the Visayan islands of the Philippines. They are one of the two only culturally indigenous group of Visayan language-speakers in the Western Visayas, along with the, Halawodnon of Lambunao and Calinog, Iloilo and Iraynon-Bukidnon of Antique. Also, they are part of the wider Visayan ethnolinguistic group, who constitute the largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group.

This fragment from mountain people of Central Panay differs greatly from the main text of the entire” Epic of Hinilawod.” On these differences, Jocano explains, “There is no doubt that there are now many versions of the “Hinilawod.” There were already many versions during the time that I was recording the adventures of Humadapnon. In the Tagarnghin area alone, there were twenty chanters. I had chosen Hugan-an because, as other chanters said, she’s the one who could narrate the entire series.”

“Another word of caution to younger researchers: the Sulod were (perhaps still are) very secretive, especially in areas having to do with their religious beliefs and rituals. While they appear at the surface to be very accommodating, there are parts of their lifeways that are not revealed easily to outsiders. Some chanters improvise their slant of the story. They skip important portions or forget them altogether; others add to make the narratives more elaborate.”

This excerpt has been posted as supplemental material for a comparative study done regarding multi-headed beings in Philippine Myth and Epics. A connecting thread is often the Hindu epic Ramayana, the Story of Rama, about a prince and his long hero’s journey. Ramayana is one of the world’s great epics. It began in India and spread among many countries throughout Asia. Its text is a major thread in the culture, religion, history, and literature of millions. Through its study, teachers come to understand how people lived and what they believed and valued. As the story became embedded into the culture of Southeast Asian countries, each created its own version reflecting the culture’s specific values and beliefs. As a result, there are literally hundreds of versions of the story of Rama throughout Asia, especially Southeast Asia.

THREE BROTHERS OF PANAY

When goddess Alunsina of the Eastern Sky reached maidenhood, Kaptan decreed that she marry. The gods and lords of the different worlds came to try their luck. However, the lovely diwata refused them all in favor of Datu Paubari, mighty mortal ruler of Halawod.

The marriage of Alunsina and Paubari was resented by the former’s god-suitors and they plotted against the newlyweds. A council of gods was called by Maklium-sa-t’wan, lord of the plains, and they all agreed that the country of Halawod had to be destroyed; it had to be flooded. However, with the aid of Suklang Malayon, guardian of happy homes, the couple was able to escape the horrible catastrophe.

A few months after the flood, Datu Paubari and his young bride, Alunsina, went down to the plains and started life anew. Some months after they had settled by the mouth of the Halawod river, Alunsina became pregnant. She told Paubari to prepare the siklot or the things necessary for delivery.

Shortly after the infants were born, Alunsina summoned Bungut-Banwa, the high priest, to perform the necessary rite to the gods of Madyaas for the good health of the children. Bungut-Banwa, after having improvised an altar, burned alanghiran fronds and a pinch of kamangyan (native incense) thrown to the fire, and fumigated the three infants. The ceremony over, the high priest opened the windows of the room, the ones facing the north. A gust of cold northerly wind blew in, and lo! the three children suddenly became handsome young men.*

A few days later, Labaw Donggon, the eldest of the three brothers, asked his mother to prepare his magic cape, his hat, his bahag (clout) and his kampilan (fighting bolo) for he was going to Handug, a place near the mouth of Halawod river where the beautiful maiden named Angoy Ginbitinan lived.

For several days he travelled across the wild plains, climbed steep mountains and traversed deep valleys, until he reached the mouth of the river. He asked for the hand of the maiden from Karimlagan. Angoy Ginbitinan’s father commanded him to vanquish the huge monster, Manalintad, which haunted the mountainside of Halawod, as part of the dowry requirement. With the aid of his magic belt, Labaw Donggon was able to kill the monster and presented its tail as a trophy of victory to the people of Karimlagan.

Labaw Donggon brought home with him his new bride. However, on their way home to Madyaas, they met a group of young men who informed Labaw Donggon that they were bound for Tarambang Burok to try their luck for the hand of Abyang Durunuun, beautiful sister of Sumpoy, lord of the underworld.

When they arrived home, Labaw Donggon left his young wife in his mother’s care and immediately proceeded to Tarambang Burok. On his way, he encountered Sikay Padalogdog, a huge man with a hundred arms who guarded the ridge leading to Abyang Durunuun’s place. Sikay Padalogdog’s anting-anting proved no match for Labaw Donggon’s talisman and, after a fight, he surrendered to the young Madyaas hero.

Labaw Donggon was successful in his venture and he brought home to Mount Madyaas his prize, Abyang Durunuun. A few days later, he again set forth for Gadlum to win the hands of beautiful Malitong Yawa Sinagmaling Diwata, young bride of Saragnayan, lord of darkness.

Riding in his biday nga inagta, a black boat, he sailed across the seas for many moons, then across the regions of the clouds, passing the land of stones, until he reached the shore of Tulogmatian, Saragnayan’s seaside fortress. As soon as Labaw Donggon set foot on the shore, he was challenged by Saragnayan. “Who are you and what did you come here for?”

“I am Labaw Donggon, son of Datu Paubari and goddess Alunsina of Halawod,” Labaw Donggon answered. “And I came here for the fair Malitong Yawa Sinagmaling Diwata.”

Saragnayan burst into loud, ill-humored laughter. He told Labaw Donggon that he was courting trouble because Malitong Yawa Sinagmaling Diwata was his (Saragnayan’s) wife. However, determined to carry out his suit, Labaw Donggon challenged Saragnayan to a duel, stating that whoever wins should have Malitong Yawa.

Saragnayan agreed and the two protagonists were immediately locked in combat. Labaw Donggon submerged Saragnayan under the water for seven years; however, when he took him out, the lord of darkness was as alive and strong as when they first met. In turn, Saragnayan pulled a nearby coconut tree and beat Labaw Donggon with its trunk. But Labaw Donggon survived the deadly lashes.

At length, Saragnayan, with the aid of his pamlang or anting-anting, defeated Labaw Donggon and imprisoned him under his house.

Meanwhile, back in Mount Madyaas, Angoy Ginbitinan bore Labaw Donggon a child, at about the same time that Abyang Durunuun also delivered a handsome baby boy. Ginbitinan’s child was named Aso Mangga while Abyang Durunuun’s infant was called Abyang Baranugon.

A few days after they were born, Aso Mangga and Abyang Baranugun went forth to look for their father whom they had not seen. Travelling night and day in their magic sailboats, the brothers reached a region of Eternal Darkness where they fought and vanquished a three-headed monster named Tabuknun. Passing the Regions of the Clouds and the Land of Stones, Baranugun and Aso Mangga reached Saragnayan’s abode. They instantly demanded the release of their father. Seeing that Baranugun’s umbilical cord had not yet been removed, the haughty lord of darkness laughed. He advised the young child to go home to his mother.

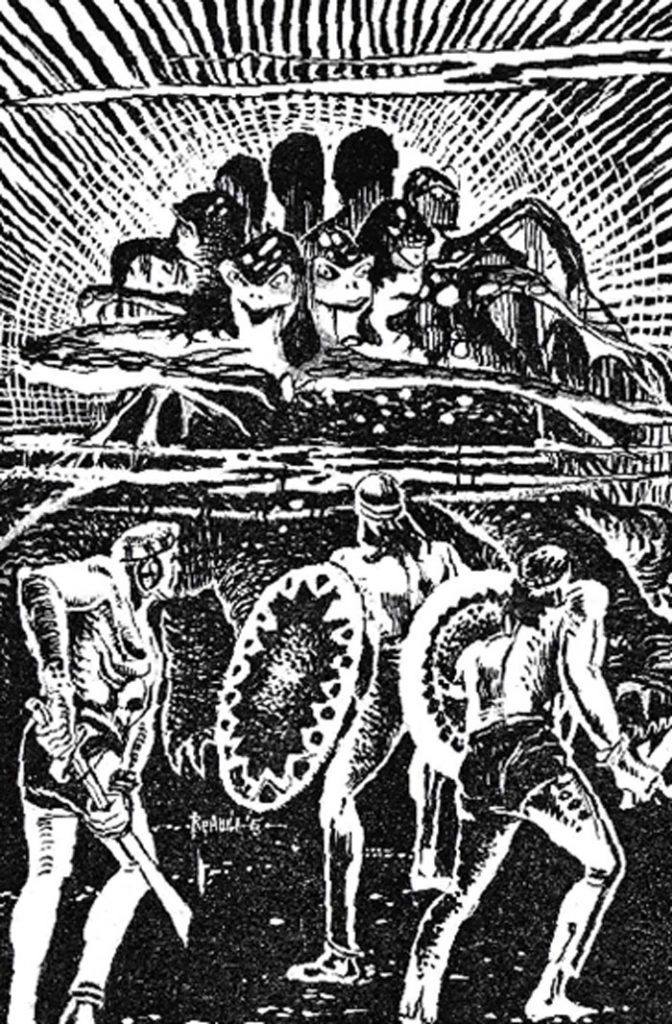

Image from OUTLINE OF PHILIPPINE MYTHOLOGY by F. Landa Jocano (1969)

Artist uncredited

Feeling insulted, Baranugun challenged Saragnayan to a duel. Thinking that it was a joke, Saragnayan accepted the challenge only to find out that he was no match for the skill of Baranugun. Having vanquished the mighty Saragnayan, Baranugun and Aso Mangga brought home their father.

Labaw Donggon’s defeat angered his brothers. Humadapnon swore to the gods of Mount Madyaas that he would go after Saragnayan’s kinsmen and followers.

Taking with him enough provision, he passed for Buyong Matanayon, skillful swordsman from Mount Matiula, and together they sailed for Saragnayan’s land. They rode in a sailboat called biday nga rumba-rumba. They travelled across the region of the clouds, passed the Land of Darkness and arrived at a certain place called Tarambang Buriraw. Here they encountered Pinganun, the seductive sorceress of Talagas Kuting-tang ridge.

Seeing Humadapnon and his friend, Pinganun changed herself to a beautiful maiden and, with all the known wiles of a woman, lured the young man to make love to her and, when night came, to sleep with her.

Humadapnon fell into the snare. He refused to leave despite the pleas of Buyong Matanayon. He became a witch! For several months, they remained. On the seventh month, Buyong Matanayon remembered that they brought along with them a good supply of ginger. And so one night, while Pinganun and Humadapnon were eating, Matanayon threw seven slices of ginger into the fire and, as soon as Pinganun smelled the odor, she begged to be excused. Matanayon knew that witches or sorcerers could not withstand the odor of ginger, antidote to sorcery.

Immediately after she had left, Matanayon struck Humadapnon unconscious and escaped with him—thus saving his friend from becoming a sorcerer of the first degree.

On and on they travelled, pursuing and vanquishing Saragnayan’s relatives. At length they reached a place called Piniling Tubig. Approaching the gates of the village, they saw a big gathering. Upon inquiry, they learned that Umbaw Pinaumbaw, datu of the region, was giving his daughter in marriage to whoever could remove the huge stone which rolled down to the center of the plaza from the mountain. Hundreds of men had tried but they were not able to budge the stone even an inch.

Humadapnon elbowed his way through the crowd. With the aid of his magic cape, he lifted the stone, to the amazement of all those present, and threw it back to the mountain. Humadapnon was hailed as a hero, and datu Umbaw Pinaumbaw gave him his daughter. It was during the wedding feast that Humadapnon heard about the beauty of Burigadang Pada Sinaklang Bulawan, goddess of greed, from a court minstrel whom the datu summoned to sing at the celebration.

Humadapnon went forth to win the hand of this goddess. On his way he met Buyong Makabagting, mighty son of Datu Balahidyong of Paling Bukid, who was also on his way to win Burigadang Pada Sinaklang Bulawan. Makabagting challenged Humadapnon to a duel. The young Madyaas hero accepted it and the two suitors fought.

Humadapnon defeated Buyong Makabagting and, the latter, knowing that he was no match for Humadapnon’s strength and power, promised to give up his suit and help Humadapnon win the charming Burigadang Pada Sinaklang Bulawan. Later they became friends and Humadapnon brought home his new bride.

Shortly after Humadapnon’s departure for the Land of Darkness, Dumalapdap, the youngest brother, also started for Burutlakan-ka-adlaw where Lubay-Lubyok Hanginun si Mahuyokhuyokon lived. He brought along with him Dumasig, the foremost wrestler of Madyaas.

They travelled for several moons until they reached a place called Tarambuan-ka-banwa where they met Balanakon, a two headed monster which guarded the Kalbangan (narrow ridge) leading to the place where Lubay-Lubyok Hanginun lived.

With the aid of his duwindi, Dumalapdap killed Balanakon. Approaching the gate of the palace, Dumalapdap was challenged by an Uyutang, a batlike monster with sharp, poisonous claws. A bloody duel ensued.

Dumalapdap and Uyutang fought for seven months, during which neither of the two protagonists seemed to have advantage over the other. On the last month, Dumalapdap took hold of Uyutang’s ankle, broke it, and with one deadly stroke from his magic dagger (iwang daniwan) he hit Uyutang beneath the armpit. The monster gave a loud cry and fell dead. So violent was Uyutang’s cry that the ridge broke into two and the earth quaked.

The old folk still say that one half of the ridge became the island of Negros and the other half became Panay.

Dumalapdap took Lubay-Lubyok Hanginun and proceeded homeward. Datu Paubari gave a feast in honor of his three sons. After the celebration, the three brothers left for different parts of the world. Labaw Donggon went northward, Humadapnon went southward, Dumalapdap, westward and Datu Paubari remained in the East.

*NOTE: This is very similar to the Old Testament narrative of Noah, whose three sons repopulated the world after the great flood, but flood and deluge myths are much older. While similarities to Western motifs may have been incorporated throughout the Philippines after the arrival of the Spanish, it is more likely possible that these myths developed similarly to Asian neighbours.

A flood myth or deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval waters which appear in certain creation myths, as the flood waters are described as a measure for the cleansing of humanity, in preparation for rebirth. Most flood myths also contain a culture hero, who “represents the human craving for life”.

The flood-myth motif occurs in many cultures as seen in: the Mesopotamian flood stories, manvantara-sandhya in Hinduism, the Gun-Yu in Chinese mythology, Deucalion and Pyrrha in Greek mythology, the Genesis flood narrative, Bergelmir in Norse mythology, flood during the time of Nuh (Noah) of Qur’an, the arrival of the first inhabitants of Ireland with Cessair in Irish mythology, in parts of Polynesia such as Hawaii, the lore of the K’iche’ and Maya peoples in Mesoamerica, the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa tribe of Native Americans in North America, the Muisca and Cañari Confederation in South America, Africa, and some Aboriginal tribes in Australia.

SOURCES:

Epic of Central Panay 2: Hinilawod, Adventures of Humadapnon, Chanted by Hugan-an, Translated by F. Landa Jocano,Punlad Research House, Inc (2000)

Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano, Centro Escolar University (1969)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.