The Ibaloy / Ibaloi are an indigenous ethnic group found in Benguet Province of the northern Philippines. The native language is Ibaloi, also known as Inibaloi or Nabaloi. Ibaloi is derived from i-, a prefix signifying “pertaining to” and badoy or house, together then meaning “people who live in houses”.

The contents of this article have been taken from various sources over the past hundred years and may not accurately represent the beliefs of the modern Ibaloy ethnic group. Beliefs among the Ibaloy area can vary from region to region.

Religious Beliefs and Rituals

The religion of the Ibaloys is that of polytheism and animism. They do notworship any god in the form of statues and carvings but they believe in spirits of ancestors whom they call amed and of a supreme being they generally call Kavuniyan or Kabunyan. The Christian God is called Shivus, who is believed to be the higher Supreme Being than the indigenous god, Kavuniyan.

Spirits and Deities

The Ibaloys believe in a number of anitos (spirits) and deities to whom they address their prayers and petitions in an appropriate ceremony. The anitos dwell in mountains, rivers, rocks, and trees and they are believed to cause illness or misfortune to an individual who destroys or disturbs their abode. The people hold feasts or ceremonies and make offerings to the spirits in order to appease them.

Two kinds of anito are known to the Ibaloys-the nature spirits that always create disasters or calamities and the ancestral spirits (ka-apuan). The ka-apuan appear in dreams or make a member of the family sick to make known their wishes. Ceremonial offerings are likewise accorded these spirits.

Among the nature spirits are:

(1) amdag -spirits that travel with the wind who carry nets to catch the souls of persons;

(2) ampasit -they dwell in caves and they are believed to mislead people who are traveling at night or at dusk;

(3) tinmongao – malevolent spirits that live in caves, stones and trees that cause injury or sickness to a person who steps on their dwelling place;

(4) pinad-eng -spirits living in the forest who own the wild pigs and chickens; hunters offer sacrifices to these spirits for a successful hunting trip; and

(5) butat-tew -spirits who group themselves to misguide people in their paths or in their activities.

The other spirits are called banig and penten. The banig are spirits of an almost dying person or one who just passed away while the penten are spirits of people who died a violent death. They live in rivers and cause the river to swell or rise when one crosses especially during the rainy days.

The Religious Functionaries

The central figures in the performance of all the religious activities of the Ibaloy are the mambunong, mansip-ok and the mankutom.

The mambunong (lit., the maker of prayers) presides in all the feasts requiring the recitation of bunong or prayers. Any one can become a mambunong as long as he learned the correct procedures sufficiently well to approach the deities and spirits, for them to grant his intercessions or to effect a cure and good fortune. One learns the procedures and prayers associated with each ceremony through constant listening and observing, or through direct instruction of a mambunong. These priests are generally classified into two classes. One class, composed for most part of women, performs rituals reserved for special ceremonies; and the other, composed of older and experienced mambunong, performs familiar rituals. The latter are called manbahi and they usually preside in special feasts afforded only by the baknang.

The person who identifies the causes of illness is called mansip-ok who determines the reason for the sickness by using a pendulum-like instrument (a string and stone) that he holds close to his forehead while mentioning the probable causes of the sickness. When upon mention of a probable cause the string swings faster and farther away, this is an indication that the mentioned cause is the reason for the person’s illness.

The mankutom (wise man), on the other hand, interprets the meaning of events. For example, when a kitchen utensil breaks during a marriage ceremony the mankutom may interpret this as a premonition for the breaking up of the couple. Certain ceremonies are then performed to remove its ill effect (A People’s History of Benguet, Bagamaspad and Pawid, Baguio Printing and Publishing Company, 1985).

Rites and Rituals

Numerous ceremonies and rituals are performed to implore the deities during important events like birth, marriage, death, and other celebrations. These deities are also invoked for good health and bountiful harvest, for the termination of an illness befalling a family member, and for voiding an evil omen. Most of the time, these rituals necessitate the butchering of appropriate sacrificial animals and the drinking of tafey. The chanting of the appropriate prayers by the mambunong is never absent in the ceremonies. In Nabaloi Law and Ritual (1919) C. R. Moss recorded about 40 different Ibaloy rituals which he classified into:

(1) ceremonies for the purpose of curing illness caused by a spirit;

(2) ceremonies related to specific events like birth, marriage, death, and certain activities like rice agriculture; and

(3) ceremonies related to offering for the spirits or deities.

The following are some of the ceremonies related to the curing of illness:

1. Ampasit –This is a ceremony offered to the pinad-eng, tinmongao and ampasit who live in rocks, trees, rivers, and the underworld . This ceremony is done to cure sore eyes and sore feet. A chicken is butchered for the ceremony, performed behind the house of the sick person.

2. Dosad -This is performed to cure chest pains. The mambunong holds a spear against the chest of a hog and starts the prayers. After the hog is butchered and cooked, the mambunong repeats the prayers, this time holding the spear against the chest of the sick person.

3. Sikop (sigop) – A ceremony for curing coughs that is done without offering animals or tafey. The mambunong takes salt and ginger that he rubs on the neck of the sick patient while praying.

4. Kolos – This is offered to the water god, Kolos, to cure stomach pains and diarrhea. A small pig or a chicken and a jar of tafey are used for the ceremony.

5. Sibisib – Principally to cure wounds, this ceremony is performed without butchering sacrificial animals. The mambunong takes the instrument that caused the wound (or if not obtainable, a substitute) and puts it over the wound while he prays.

Some ceremonies related to specific events and activities are:

1 . Dasadas – Before a family occupies a newly built house, they perform this ceremony asking for good health and wealth from Kavuniyan, the deities and other spirits. A pig is butchered for this occasion.

2. Begnas – This ceremony is performed outside the village and is done before harvest, during famine or when death occurs. This involves the butchering of pigs and the simulation of a headhunting raid.

3. Amlag -This ceremony is done to release a person believed to have married a spirit. A small chicken or pig is offered, but tafey is not necessary in the performance of this ceremony.

4. Basal-lang – This ceremony is performed after childbirth so that the new mother would not experience profuse bleeding or suffer skin diseases.

5. Sabosab -This is a ceremony performed to restore good relations between quarreling persons, to cure. deformities and to remove the ill effects of activities done against the traditions and customs of the village.

The ceremonies related to the offering for spirits and deities are:

1. Podad – This is a ceremony offered to a person who committed suicide.

2. Tawal -This is a ceremony intended to call back the spirit of a person believed to have been imprisoned in an unknown spirit world. Chickens and tafey are offered to the spirits.

3. Lawit – When one is frightened or when he falls, it is believed that his spirit leaves his body and wanders off. This ceremony is performed to call back the wandering spirit and make the person whole for him to live well.

4. Tomo – This is a ceremony performed to cure an insane person. A dog is offered to the spirits of the departed ancestors (who are headhunters) that are believed to have caused the insanity.

5. Topya – This is a done to counteract a curse and to cure illness or physical deformity resulting from witchcraft (padpadja). Sacrificial animals like dogs, chickens, ducks, and goats are butchered during this feast.

Ibaloi Tattoos and Mummification

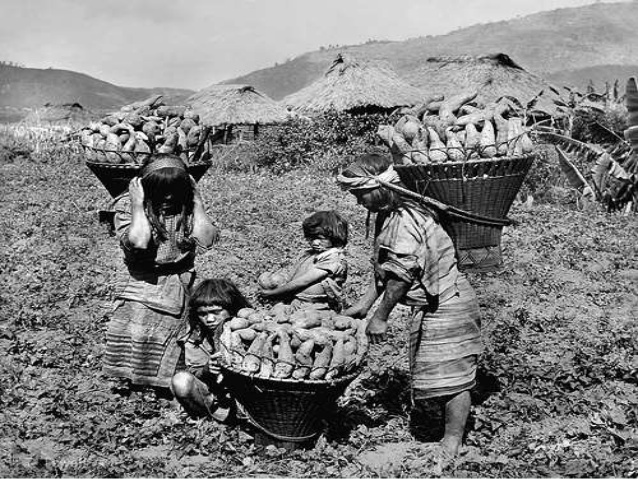

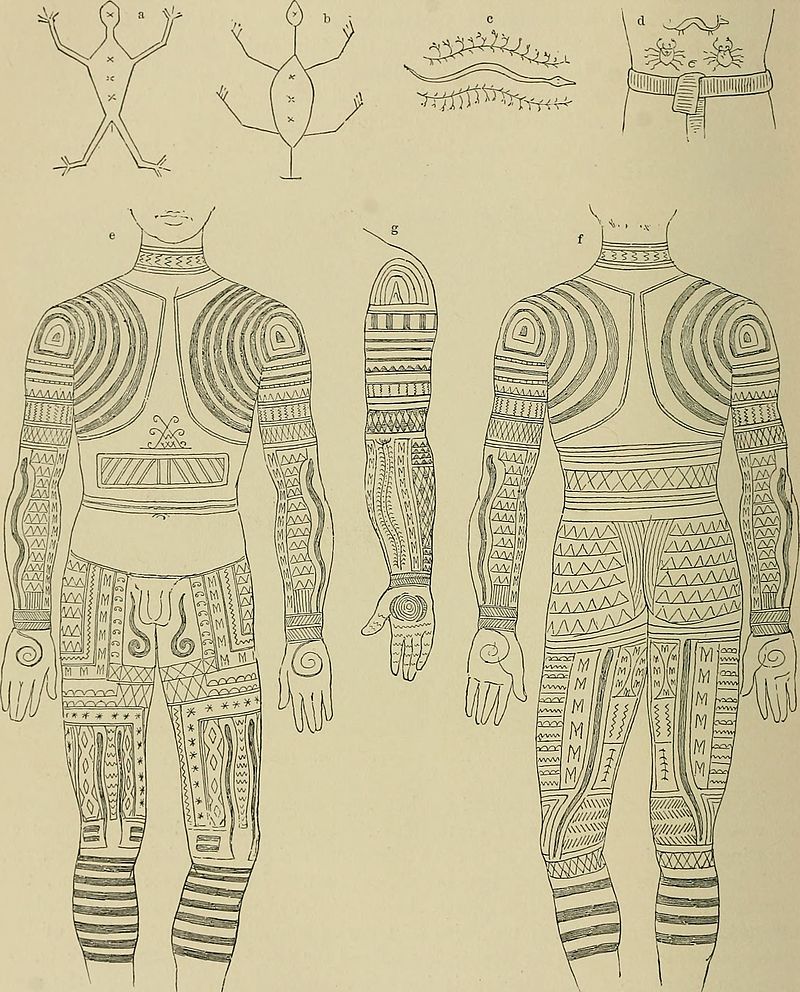

Among the Ibaloi and Itneg people (also called the “Tingguian”), tattoos are known as burik. It is practiced by both men and women, who were among the most profusely tattooed ethnic groups of the Philippines. Burik traditions are not prevalent today.

The most characteristic burik design was the wheel-like representation of the sun tattooed on the backs of both hands. The entire body was also tattooed with flowing geometric lines, as well as stylized representations of animals and plants.

The Ibaloi once mummified their honored dead and laid them to rest in hollowed logs in the caves around what is now the Filipino municipality of Kabayan. In life, these ancient people had won the right to be covered in spectacular tattoos depicting geometric shapes as well as animals such as lizards, snakes, scorpions, and centipedes. “According to nineteenth-century ethnographic accounts, Ibaloi head-hunting warriors revered these creatures as ‘omen animals,’” says Smithsonian anthropologist and tattoo scholar Lars Krutak. “The sight of one before a raid could make or break the entire enterprise.” After successfully taking the head of an enemy in battle, a warrior would have these propitious animals permanently etched onto his body.

Some Kabayan mummies also feature less fearsome tattoos, such as circles on their wrists thought to be solar discs, or zigzagging lines variously interpreted as lightning or stepped rice fields. “All these tattoos seem to depict the surrounding environment,” says Krutak, who notes that the increased attention paid to the mummies in the last decade has helped fuel a resurgence in traditional tattooing, which had largely died out. Today, thousands of people tracing their descent to the ancient Ibaloi wear designs on their skin modeled after those of their ancestors.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES: Archaeological Institute of America, Ibaloi Mummy, November/December 2013, https://www.archaeology.org/

Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera, Cordillera Schools Group Inc., New Day Publishers, 2005

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.