The Ifugao call themselves as i-pugao or “inhabitants of the known earth”; other variations of the name are Ifugaw, Ipugao, and Yfugao. They live primarily in the province of Ifugao in Central Cordillera, in Northern Luzon. The name is supposed to have come from ipugo which means “from the hill.”

“The peoples of the Philippines have a rich and varied mythology as yet but little explored, but which will one day command much attention. Among the Christianized peoples of the plains the myths are preserved chiefly as folk tales, but in the mountains their recitation and preservation is a real and living part of the daily religious life of the people. Very few of these myths are written; the great majority of them are preserved by oral tradition only.” – H. Otley Beyer

In the Ifugao story of the first man and woman, it is impossible not to see the similarities to that of Adam & Eve. It is possible, of course, that this is a biblical story which was brought in by some wandering Christians several generations past; but the story evolved into something uniquely native. As the American anthropologist, H. Otley Beyer pointed out regarding the flood myths of the Philippines, “I see no good reason why the story should not also be [seen as] a native development in spite of its similarity to the Hebrew myth.”

I felt it was important to share this myth, over the more popular story of “Malakas and Maganda”, because it exemplifies the need to examine how these myths evolved through all aspects of migration and foreign influence. Christianity was not the first religion to make its mark on Philippine Myths. Before this, Islam and Hinduism greatly impacted these stories. Spanish colonization had a very negative impact on the preservation of pre-Hispanic culture, so it is like finding a gem when a story has been borrowed and evolved into something relevant to the people of that region. Further, unlike the myth of “Malakas and Maganda”, the following story of “Uvigan & Bugan” has remained relatively untouched by the Filipino poets of the 20th century.

Ifugao Story of Man and Woman

To the Ifugao’s, Mak-no-ngan was the greatest of all the gods. It was he, they believed, who created the earth and the place of the dead.

The place of the dead was divided into many sections. The most important of these sections were Lagud and Daya. Lagud was set aside for those who died of sickness. They were the most favored my Mak-no-ngan. Daya was set aside for those who died of violence. They remained restless and unhappy, until their deaths were avenged by their relatives.

After Mak-no-ngan created the earth, he made Uvigan in his image. Uvigan, then, was the first man. Mak-no-ngan gave him the entire earth to enjoy. But he remained unhappy just the same, because he was lonely.

Seeing this, Mak-no-ngan made Bugan, the first woman. Then he told Uvigan, “Take this woman and be happy with her.” And for many years the couple lived in innocence, happiness, and peace.

Now, on the earth, there grew a tree which was different from any other. From the very beginning, Mak-no-ngan had warned the couple against it. “Don’t eat its fruit,” he told them, “because it is evil. It will only make you unhappy.”

But Mak-no-ngan’s warning only made Bugan all the more curious about the tree – especially since it was beautiful and its fruit looked tempting. She tried hard to keep away from it, but she could not help herself. Again and again, almost against her will, her feet would lead her to it. And her mouth would water as she gazed at the ripe fruit.

Finally, Bugan could not contain herself any longer. One day, she went straight to the tree, plucked one of the fruit, and sank her teeth into it. It was good. She liked it so much that she was seized with a desire to share it with Uvigan.

And so she went to Uvigan, saying, “Here, Uvigan, taste this.”

“Isn’t that the fruit that Mak-no-ngan forbade us to eat?” Uvigan wanted to know.

“Yes, and it’s very good,” said Bugan. “It tastes better than any other fruit I’ve eaten.”

“But what will Mak-no-ngan say?” asked Uvigan.

“He doesn’t need to know,” said Bugan.

“He will, though,” said Uvigan. “He’s a god, and he has ways of finding out.”

“Then why didn’t he punish me the moment I plucked the fruit?” Bugan asked.

“Just the same, it’s wrong and wicked of you to have plucked and eaten the fruit,” Uvigan pointed out. “You should not have disobeyed Mak-no-ngan.”

“Well,” said Bugan, “I don’t see, anyway, why he should have forbidden us to eat the fruit in the first place, unless he wants to save it for himself. But he can’t possibly eat all of it. There’s plenty and to spare.”

“Perhaps you’re right,” agreed Uvigan. “Let me have a bite of the fruit.”

Bugan gave it to him. He took a bite, and another, and another, as his eyes lighted with pleasure.

Nothing happened to Uvigan and Bugan right away. But little by little, they grew discontented and unhappy. And they began to quarrel with each other. For evil had entered their lives.

Uvigan and Bugan bore many children. But they were all unruly, disobedient, and troublesome. And after some years, Uvigan died in deep sorrow, leaving Bugan alone to run the household.

The children of Uvigan and Bugan grew more and more wicked, until Mak-no-ngan could no longer control his anger. To punish them, he caused the rice plants to wither and die; so that, in the end, they had nothing to eat.

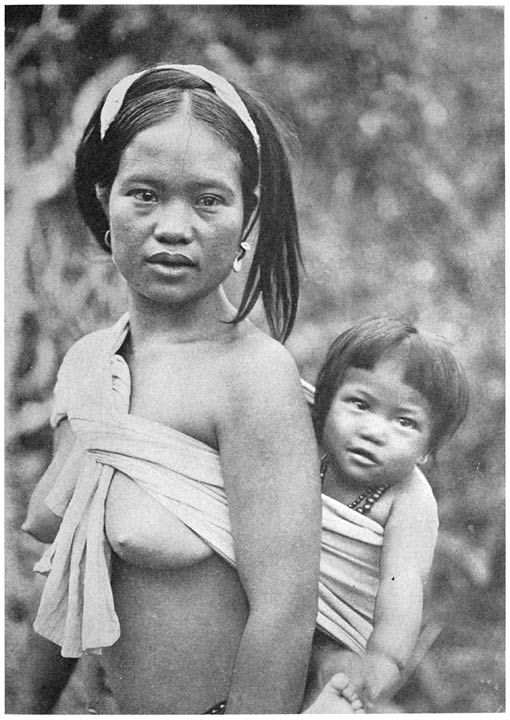

Filled with pity for her hungry and suffering children, Bugan knelt on the ground and prayed that they might live. Then, with a great effort, she took hold of her breast and pressed them hard, until two streams of milk flowed to the ground.

Bugan’s milk kept some of her children alive for a while, but, as it slowly ran out, she became more and more anxious about the welfare of her children. And she continued to press her breasts harder and harder, until blood flowed in torrents to the ground.

Seeing Bugan’s sacrifice, Mak-no-ngan took pity on her and on her children. And so he made The rice plants grow once more. This time, however, some of the plants bore white grains; while the others bore red grains. The white grains were Bugan’s milk, while the red grains were her blood.

SOURCE: I.V. Mallari and Laurence L. Wilson, Tales from the Mountain Province (Manila: Philippine Education Company, 1958), pp. 2-4

ALSO READ:

VISAYAN Origin Myth: Creation of the Sun and Moon

NEGRITO Origin Myth: Creation of the World

IGOROT Origin Myths: The Creation

MINDANAO Origin Myths: The Earth and its Inhabitants

BICOL Origin Myth: The Creation of the World

The TAGALOGS Origin Myths: Bathala the Creator

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.