|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The present lloko population is basically Christian. The majority belongs to the Roman Catholic Church. The rest are affiliated with other Christian denominations such as the Iglesia Filipina lndependiente, Iglesia ni Cristo, Baptist Church, Methodist Church, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Church of the Latter Day Saints. Contemporary lloko religiosity is nevertheless largely a syncretism of the above institutions’ influences and indigenous beliefs.

There is almost nothing written about Ilocano beliefs at the first Spanish contact. I find it very difficult to answer emails that ask what early Ilocanos wore, if they tattooed themselves, and what adornments they may have displayed.

We can glean insight from the knowledge that extensive trading between the Ilokanos, Tingguians, Igorots, and other Cordillerans, other Southeast Asians, Chinese, and Japanese was already taking place in coastal settlements like Vigan at the time of Spanish arrival.

________

The following is according to Isabelo Florentino de los Reyes and may provide some insight into many of these questions:

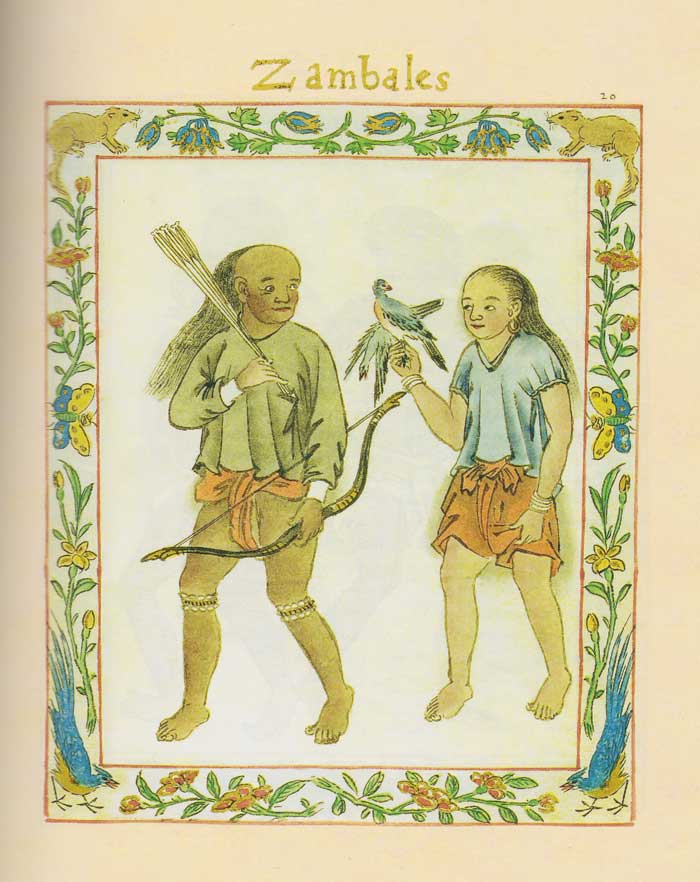

At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Ilocanos had long hair like the Igorots, but it was not as long as the Cagayanons’ whose hair covered their backs.

Women wore their hair charmingly twisted into a bun on the crown of their heads. Both men and women took care to have shiny black hair using, for the purpose, shampooing decoctions made out of the barks of certain trees, coconut oil mixed with musk and other perfumes, gogo, and lye made out of rice husk that is still used today in Ilocos.

From childhood, they polished and sharpened their teeth with betel nut husk and stones; they would make them all even or sometimes they would make them serrated like the teeth of a saw. In order to preserve them, they would color them red or black like the Igorots. The rich, specially the women, decorated or incrusted them with gold either to make them stronger or more flashy.

Men entertained themselves by pulling the hairs out of their beards using clam shells fashioned into tweezers; that is why they did not have beards and mustaches like they do today.

Women, and men in some places, adorned their ears with big gold rings for which purpose they pierced their earlobes as children. The more torn and bigger the holes, the better they liked it for being so fleshy. There were two kinds of ear-piercing: one for a small earflap, another for a bigger one. A chronicler wrote the foregoing about Filipinos in general. I believe that the old Ilocano women did not use earrings unlike today’s women for whom they are a matter of coquetery. Although the old Ilocano men do not remember if their ancestors used earrings, it is more than likely that they did so in imitation of their lgorot neighbors.

The men wore a long narrow cloth (the Tagalogs called them potong, perhaps “bangal” in Ilocano) that they either wrapped around their heads like the Tinguians or fashioned into a Muslim-style turban. Those who prided themselves for their courage, draped the potong over their shoulder with the embroidered ends touching the back of their knees. The colors of the potong depicted the feats and status of the wearer: red indicated that the wearer had killed someone; only he who had killed seven or more could wear a striped potong. But thirty years after the Spanish arrival, in the time of Morga, men were already wearing hats.

Men used a collarless waist-length fitted jacket made out of cloth that was sewn in front, like the Tinguians’ koton. It had short, wide blue or black sleeves. The principalia had them in fine red chininas crepe from India or in silk.

“For trousers, they wore a richly colored cloth, usually goldstriped, rolled up at the waist, and passing between the leg such that they were decently covered until mid-thigh; from the thigh down, their legs and feet remained uncovered.” They called them bahaques. So wrote the author of Lavor Evangelica (Evangelical Labor) and Morga corroborates the observation. Nowadays, the Ilocano women have followed suit: they gather up their skirt m front, pass it between their legs and hitch it at the back of their waist, “thereby covering until their mid-thigh and leaving the rest down to their legs and feet uncovered.” If today the Ilocanos are doing it, it must follow that the

Ilocano men were doing it before.

Their main adornments were precious stones, gold jewelry, and costly trinkets. Like their Tinguian neighbors, the Ilocano men hung many gold chains around their necks “fashioned like spun gold and linked in the same style as ours,” according to Morga. Gold and ivory bracelets called kalombigas were wound around their arms from hand to elbow and some wore strings of carnelian, agate, and other blue and white stones that caught their fancy.

They also wore anklets or strings of these same stones as well as many strings dyed black. They went around barefoot; but soon after the Spaniards arrived, however, they started wearing shoes according to Morga. Many women wore gold-embroidered velvet slippers.

They wore rings of stone and gold on their fingers.

They used a kind of sash: a rich shawl draped over the shoulder and tied below the arm.

The women wore a kind of multicolored overskirt over a white floor-length underskirt that was usually as wide on top as at the bottom.

It was gathered at the waist and the pleats were then paced at one side. We call it salupingping in Ilocos where it is still used today.

Whenever they went out, they wore multicolored shawls. Ladies of the principalia wore crimson silk or other cloth woven with gold and decorated with thick fringes. So say Morga and Father Colin of Filipinos in general. During ceremonies, the principalia and others wore on top of those clothes a black, floor-length cloak with long sleeves; the old ladies also used them. This manner of dressing would be the one that replaced the shiny black shawl of the Ilocano women.

Women wore jewelry of gold and precious stones at their ears at their wrists, fingers and neck.

The Ilocanos would prick themselves then they would rub the area with permanent black pitch powder or smoke; they did not do it as much as the Visayans however, who painted themselves as a matter of course.

“In time the practice became more popular and dividing society into different classes brought with it some requirements; the Indio principalia showed off their bedaubed clothing while the common man of the people was naked,” writes Morga y Jimenez.

Indeed, the Ilocanos must have been naked in the beginning with only a small loincloth of smoothened balete like the Igorots of Abra, and they most probably only started wearing clothes when the Asians brought over cloth from their own countries which they have used since then to exploit the wealth of this country.

However, when the Spaniards arrived, the rich wore clothing that, according to all the chroniclers, was luxurious and in good taste.

______

Contrary to what de los Reyes states regarding the introduction of clothing, it is unknown exactly when Ilokanos began weaving, and they, along with many groups throughout the archipelago, likely began the practice long before trade with foreign countries. It seems apparent that the Iloko woven fabric of cotton, otherwise known as abel-Iloko was already a coveted possession in pre-Hispanic times. Its popularity was furthered as it reached more foreign shores through the Galleon Trade. Moreover, the thick, and therefore more durable, abel-Iloko was preferred over other fabrics from other places and countries for galleon and boat sails.

PHOTO: Jessica Zafra

Aside from gold processing and smithing, abel-weaving, and salt-making (used for trade in the Cordilleras), the Iloko people were likewise engaged in pottery (the indigenous damil and later, the Chinese introduced burnay) and boat-building. The latter suggests that the Ilokanos were also seafarers who may have sailed for trade or in search for better settlements in other parts of the island or archipelago. Intermarriage among the Ilokanos, the Cordillerans, other indigenous communities, and foreign traders (especially the Chinese) took place as a natural consequence of the trade relations. This, in turn, resulted in further, “and perhaps better, socio-economic and cultural activities and understanding among the ethnic groups. As such, there existed not only a vibrant economic development within the region, but a dynamic socio-cultural exchange as well.”

With the above considered, we should turn our minds from thinking all cultural influences came to the Ilokano from afar, and contemplate that in certain instances the cultural exchange very likely happened the other way as well.

SOURCES: de los Reyes, Isabelo (2014) History of Ilocos Volume 1 & 2, With an English Translation by Maria Elinora Peralta-Imson, UP Press

Ingel, M.L.I. (2006) The Iloko, National Commission for Culture and the Arts

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.