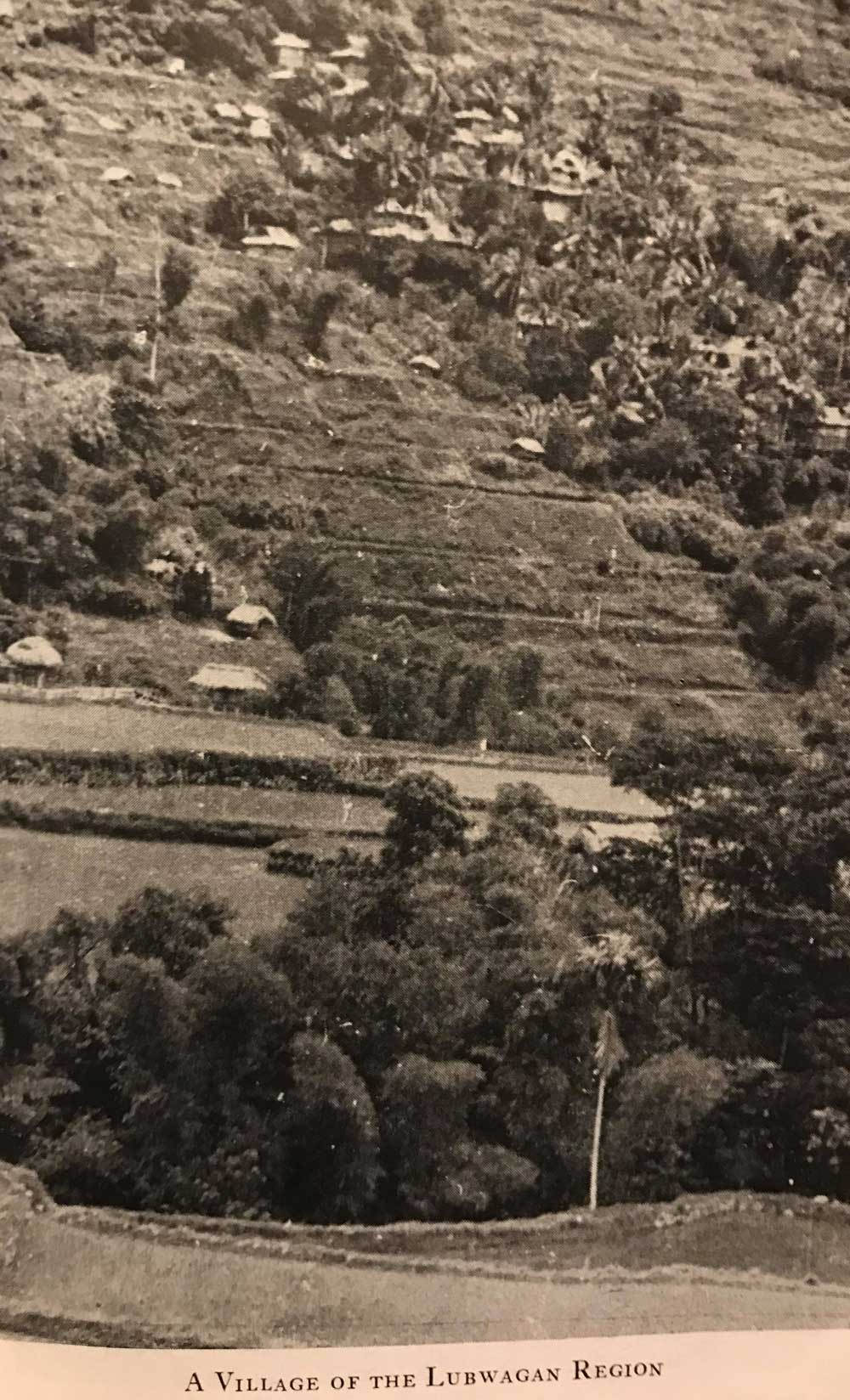

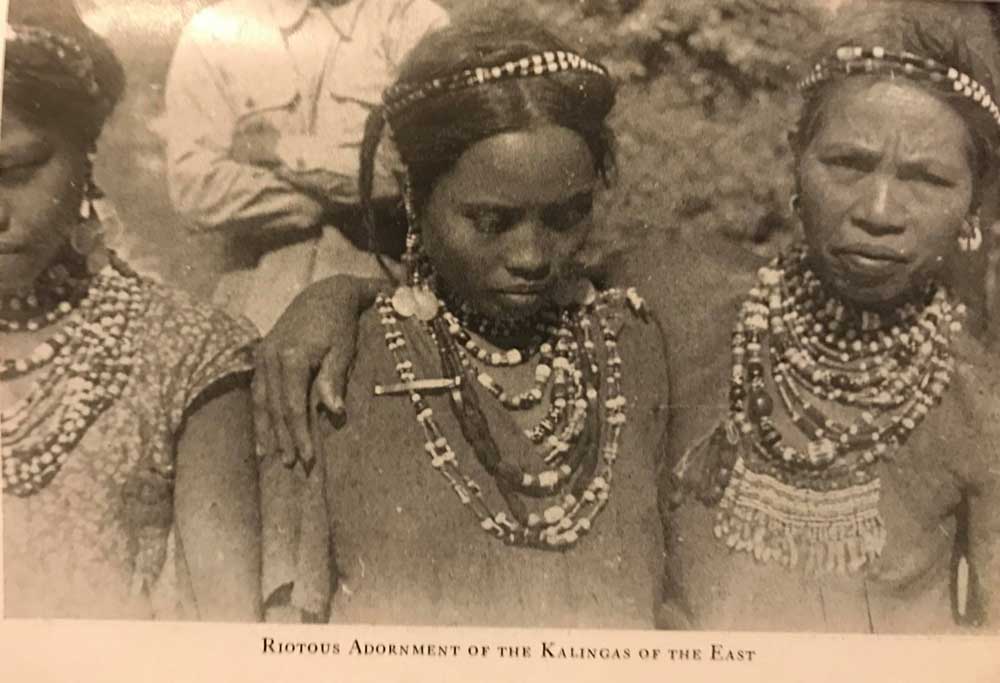

The Kalinga people are highlanders and the most extensive rice farmers of the Cordillera peoples, having been blessed with some of the most suitable land for both wet and dry rice farming. Like the Ifugao, the Kalinga are prolific terrace builders. The Kalinga are also skilled craftsmen, well-versed in basketry, loom weaving, metalsmithing, and pottery, the last centred in the lower Chico River Valley. Until recently Kalinga people could be identified from a distance by their distinctive body art.

Please note that the following study is from Roy Franklin Barton‘s 1949 report, “THE KALINGAS: Their Institutions and Customs Laws,” and may not represent the beliefs of modern Kalinga people.

The Kalinga religion is more nearly similar to that of the Tinggian of Abra than to that of any other tribe except it possibly be the Apayao. There is a great difference between these mountain tribes in the respect of their pantheons. The contrast is greatest between the Ifugaos and their immediate neighbors to the north and west, the Bontoks and Kankanai. The Ifugaos probably have the largest pantheon on record, but no deity is supreme; the Bontoks and Kankanai are about as monotheistic as a ‘primitive’ folk ever are. The Kalingas and Tinggians occupy a middle position, having a supreme deity and several classes of others.

SUPREME DEITY:

The supreme deity is Kabunyan, sometimes called Kadaklan, ”The Greatest. ” By derivation Kabunyan means ”those to whom offerings are made,” ”those for whom it is killed.” In Ifugao the word designates the Skyworld, the region where the greatest number of deities dwell. Among the Kankanai the supreme deity is sometimes called Kabunyan, sometimes Lumauwig the name of the culture hero. Parts of Kalinga that were settled from Bontok still have Lumauwig as a local god. The stem of this word, lauwig, means ”field hut” in some Malayan languages; in Tagalog, lauwigan means an expanse. The god Lumauwig ts a personification of the ”miraculous increase” of crops; where he walked he left the ”miraculous increase.”

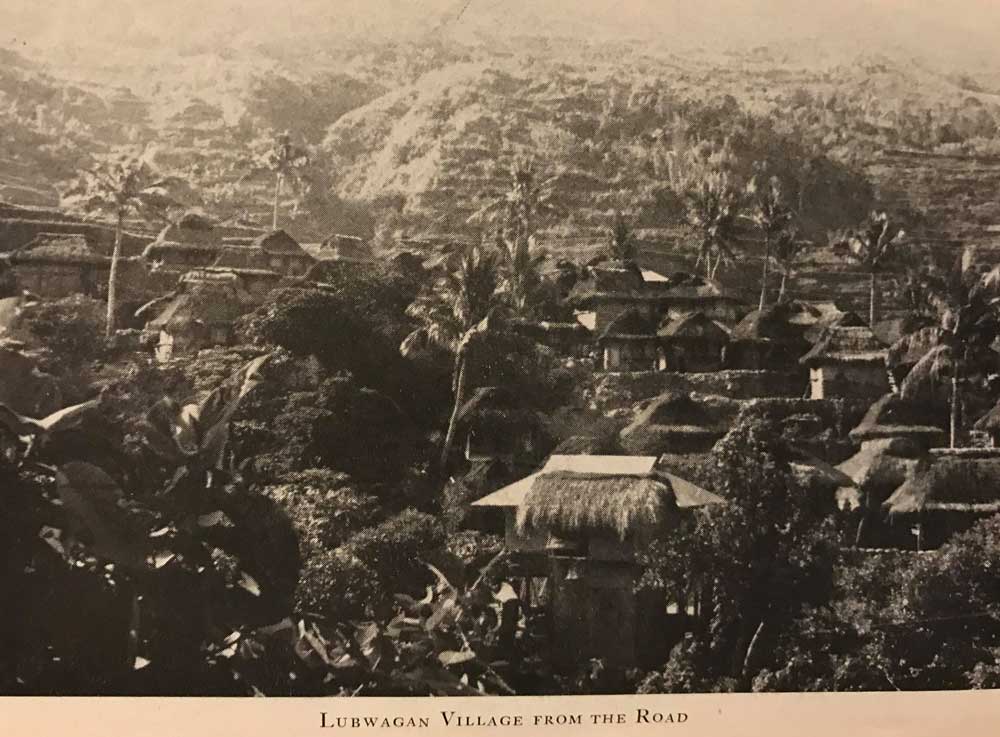

Central Kalinga, centering around Lubwagan, has little faith in the ”miraculous increase” and does not seek it , thus constituting an outstanding exception among Philippines peoples. After the rice has been planted, husband and wife go out to the fields with a chicken and some rice wine. They offer the chicken to the ancestral souls believed to he lingering about or inhabiting the fields for the Kalingas bury their dead there. They pray especially to the souls of those who built or improved the fields as follows:

Ancestors of ours who built this field and from whom we inherited it, have pity on us. Do not draw your living from it, do not harvest some of the crop. We are killing a pig (or chicken) to ”end” your staying here. Do not come again.

Our god, Kabunian, who is the Greatest (”Kabunian un Kadaklan”), drive those spirits away and make this soil furnish us good crops. Do not permit these spirits to come again, thou who art the greatest and supreme above all others.

Then they put rice, meat, and bananas on the dike and say, ”This is the end of you. Eat and depart. “ Thus it would appear that the central Kalingas believe in the likelihood of diminishment of the crop rather than in the possibility of its miraculous increase.

OTHER DEITIES AND SPIRITS:

Below Kabunian there are various lesser deities:

KiDul is the god of thunder.

KiLat is the god of lightning.

Sun and moon occupy no important position. Some informants say that they are not regarded as gods at all. The moon, however, gives omens.

DumaNig is a demon which possesses the moon (Bolan) and causes her to devour her husband the sun (Ageo)

NamBisayunan is the howl or shriek that is heard during a storm.

Libo-o d Ngatu, ”Clouds of the Skyworld ” cause sickness.

Maman are beings derived from a second death of souls in the Afterworld; they are perceptible in red light, as on a rainy day near sunset. They may cause sickness.

Bungun ts the god of the rainbow.

The mamlindao are hunting spirits.

The bulaiyao live in big rocks, hot springs, and volcanoes. They have a fiery appearance which they can turn on or turn off. They capture or devour souls. Gulilingob ud Tangob is the strongest of all the bulaiyao. This class is, of course, the same as the Ifugao tayaban.

Dumabag is the god of the volcano at Balatok.

Lumawig is the local god of the Mangali-Lubo-Tinglaiyan district.

The Angako d Ngato are demons that afflict with sickness.

The Angtan are goddesses or demons that depress men, bring worry and bad luck.

The aLan are cannibal or ghoul spirits that figure largely in myths and folktales as carrying away or devouring souls and as producing many kinds of transformations in men and in themselves.

The anitu are the souls of the dead. In lfugao the ancestral souls are besought to confer benefits and to support the living, although they are also blamed for death and sickness. On the other hand, the Kalingas appear to expect no good from them and regard them as a bad lot. A Kalinga prayer for relief of sickness is thus reported by Pedro Bingson:

“You relatives of this person who died long ago … accept this pig, which we have killed to satisfy you for making this person sick. Have mercy on him, for he alone is able to care for his family and, and what is your purpose for making him sick, since you, his relatives, have died?

Therefore,I pray you to please stop holding his spirit so that he may recover by tomorrow.

Thou, most gracious Kabunian, I pray thee have mercy on this person, for thous art the greatest person we know on earth who is able to cure sickness. This pig is sacrificed in the name of the relatives -and unto all the persons who have died in this locality.” (*Christian influence is noted in the wording of the prayer)

An informant told me that the following ought to he added to this prayer to make it complete: ‘‘Kabunian, who is the greatest, the wisest and strongest of all and who can stop the cruelty of the anitu, stop those bad spirits and defend this person.”

The pinading are extraordinary souls of the dead that have attained a superior power and existence. The Batak of Sumatra have a similar class. They live in the village or its outskirts, some of them in highly prized jars. Pinading, derived from ancestral souls, punish their descendants for wrong actions especially actions against the family interest. Some pinading are derived from souls of slain enemies or possibly are spirits that inhabit the boxes containing bits of skulls taken in head-hunting.

In western Kalinga there are guardian stones called baiyong; three or more in number stand upright in the ground, sometimes with a stone laid horizontally on the ground in front of them. They remind one of similar stones in Sumatra, the Celebes, and other islands of Indonesia. Each pangat has one on his house ground, and so do some other head-hunters. Visitors from other towns on entering the village will not neglect to lay a runo tip, its blades tied into a knot, on the first baiyong they pass. Heads taken in war are left for a while on the horizontal stone or on a red cloth spread in front of it. Likewise betel nuts must be left for them whenever anybody in the village makes an important feast. ”Spear grass” called baiyog is planted around them.

The Kalingas are confused about whether there is power in the baiyong itself or whether the stones are the habitation of spirits (as the skulls are that hang on the Kayan’s veranda in Borneo). It would appear that we here have to do again with the village-guardian cult of the Batak and several other Indonesian groups. The knotted leaves which a visitor to the town lays on the baiyong are probably magic to tie up the ferocity of the stones or of their indwelling spirits so that they will not ”bite” him. If he should neglect this, he would be seized with a fearful bellyache when he returned to his village, and the only cure would be to carry a chicken or small pig and some basi or rice wine to the owner of the baiyong and to beg the latter to sacrifice for him so that he might get well. The Ifugao pili cult of property guardians operates the same way and may be a degeneration of the baiyong.

KALINGA COSMOS:

The Kalinga cosmos consists of five regions:

Pita, the earth;

Ngato, the skyworld;

Dalum di pita, the underworld;

Daiya or Suyung, the upstream region; and

Lagod, the downstream region.

Ambagdukan means both ”a line at right angles across the river (at Lubwagan roughly EastWest)” and ”on both sides of the river” figuratively, , , everywhere.” Lagod and Daiya likewise mean in Lubwagan roughly North and South, respectively.

The region of souls is called Langit (in some regions Kakalading) and is located in Ngato, the Skyworld. There, the souls live much as on earth; they own property and live in kinship groups. The soul is ashamed to present itself without property to his kindred: for that reason, the surviving kindred on earth must sacrifice carabaos and pigs for the soul to take with it. Formerly, these were sacrificed on the second day after death at present on the first day.

After the soul has delivered them, it is said that a part of it returns to its house and remains until after the rites just described (called yabyab) are performed. Then it leaves the house, but remains in the neighborhood until it is dispatched to Kakalading. Apparently, there is here an attempt to unify conceptions of multiple souls, or else clashing concepts of the soul carried by separate streams of immigrants into the habitat.

MYTHS:

Myths are used in ritual less extensively than in Ifugao and in about the same way as the Kankanai use them; the ritual myths are either formulas made to justify a rite or else they are abbreviated myths having very ancient motifs. They end in a fiat, of which the following, from a sickness rite, is an example:

Ofai! Makaan-ka pai, ta anan sap sapu-ak Di sangsangEm; ta pamman Di KabuLiyan intoDtuDu no adi tutuwa? Ofai! Makaan-ka pa amin!

(“Ojai! Get thee hence, because I am doing thy sangsang rite, and why should Kabunyan have taught it it if it be not true? Ojai! Get hence, all!”).

Myths used ritually are called abungeL.

KALINGA PRIESTHOOD:

The priesthood is almost entirely in the hands of women. Entry into it is always in answer to a “call”, and is in a sense, compulsory: the woman begins to sleep badly, has many dreams, grows thin, lacks appetite, believes that her soul has married an anitu and that she can extricate herself from the condition only by becoming a priestess (mangaalisig). Or she may become conscious of the call from getting a stomach upset after she has eaten foods that are taboo to priestesses: eel, dog, certain fish, meat of the cow (but not carabao). She is said to be taught the rituals by the gods themselves, not by the older priestesses. But, of course, she has been watching and hearing these since she was a little girl and wondering whether fate would call her to be a priestess when she grew older.

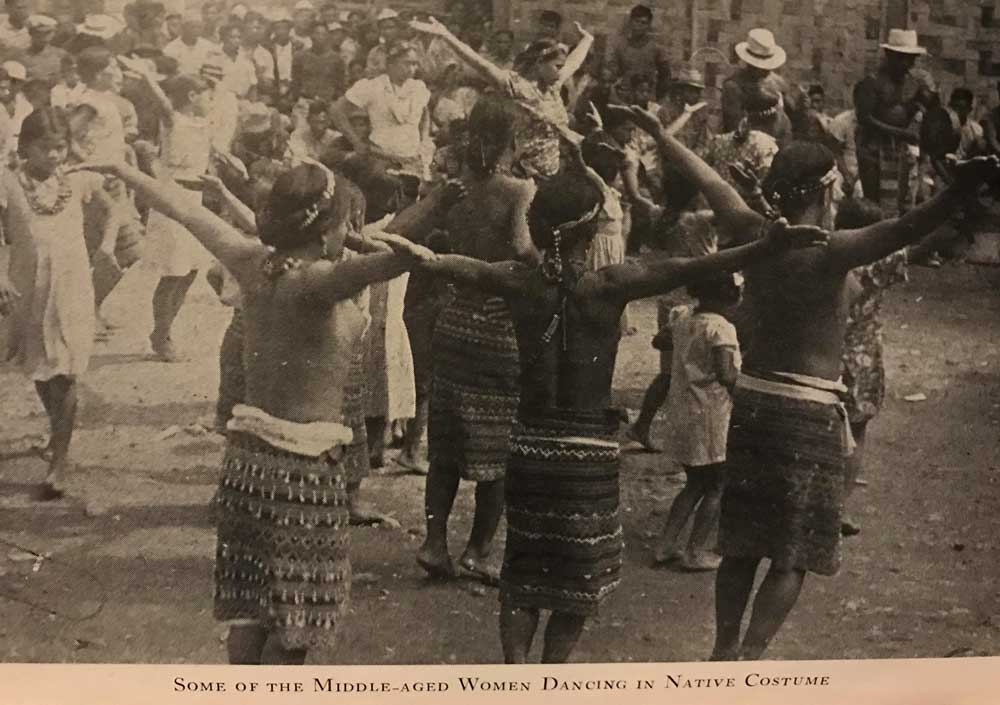

Priestesses begin their office at from about thirty-five years of age onward. About one out of fifty old women are priestesses. For their officiations they receive the lower jaw and jowls of the pig and half of the liver, or if they have plenty of meat at home already, fifteen bundles of rice, a ganta of mangos, or a peso or two. They never ask for a fee.

Men are much more rarely priests, but there are a few, and some of them have great renown. Priests formerly concerned themselves mainly with head-hunting rites, but, now that there is little or no use for these, there is little use for priests, except the few exceptional ones who undertake to cure sickness. A Christianized young Kalinga told me about a cousin of his who, he said, had ”disgraced” him. This cousin was a graduate of a mission high school, but had reverted to the native religion and become a medicine man. He had ”gotten into this work” through dreams in which he saw many ”true” visions. He plans his rites systematically and writes the program of them out beforehand on a slip of paper. Some of his ceremonies last a day and a half; people come from far to enjoy the privilege of his officiations. ”I’m really ashamed for my cousin, but I have to forgive him because he effects many marvelous cures, ” said my informant.

SOURCE (Photos and Text):

THE KALINGAS: Their Institutions and Customs Laws, Roy Franklin Barton, The University of Chicago Press, 1949

ALSO READ: IFUGAO DIVINITIES: Philippine Mythology & Beliefs

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.