Karakoa were large outrigger warships from the Philippines. They were used by native Filipinos, notably the Kapampangans and the Visayans, during seasonal sea raids. Karakoa were distinct from other traditional Philippine sailing vessels in that they were equipped with platforms for transporting warriors and for fighting at sea. Boats were the only Philippine transportation, and all commercial and political contacts depended upon them. Trade included the local exchange of foodstuffs, the exploitation of special marketing patterns, and the distribution of imports like Chinese porcelain throughout the archipelago. Slaves were taken in raids called mangayaw by trade-raiders whose exploits were acclaimed in lyric and legend. Trade-raiding formed the basis of pact between maritime leaders in which precedence was expressed in terms of personal deference rather than political domination. Communities that did not have the means for such trade-raids achieved security through alliances by blood, marriage or vassalage with those who did. The karakoa may therefore be seen as the key to the political scene in the sixteenth-century Philippines: those who had them dominated those who did not.

THE PLANK-BUILT MAN-O-WAR

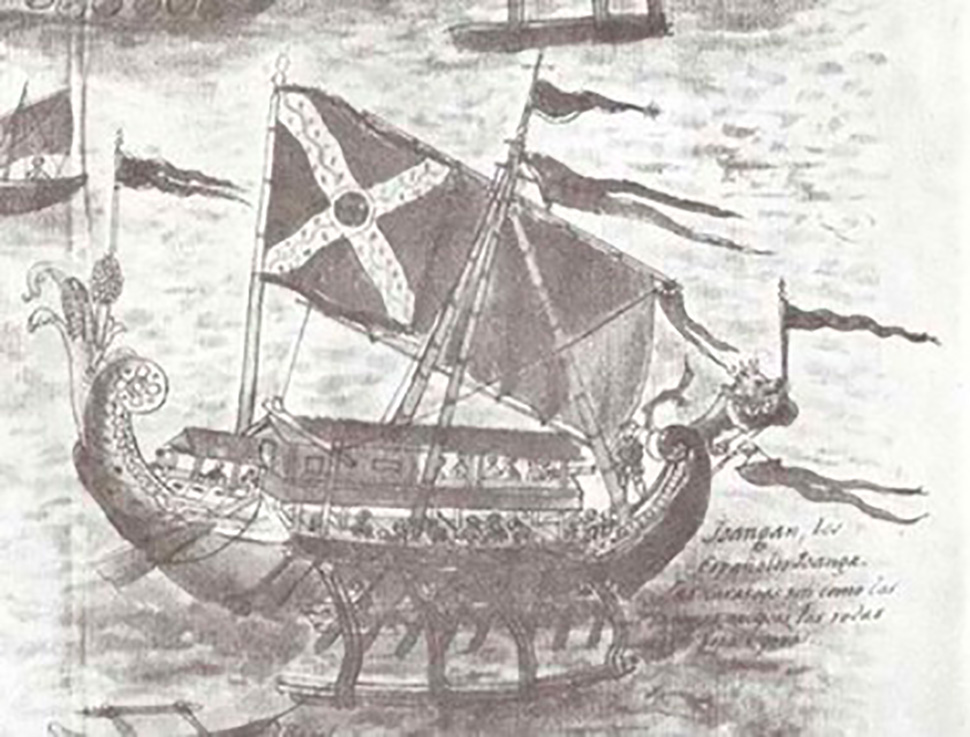

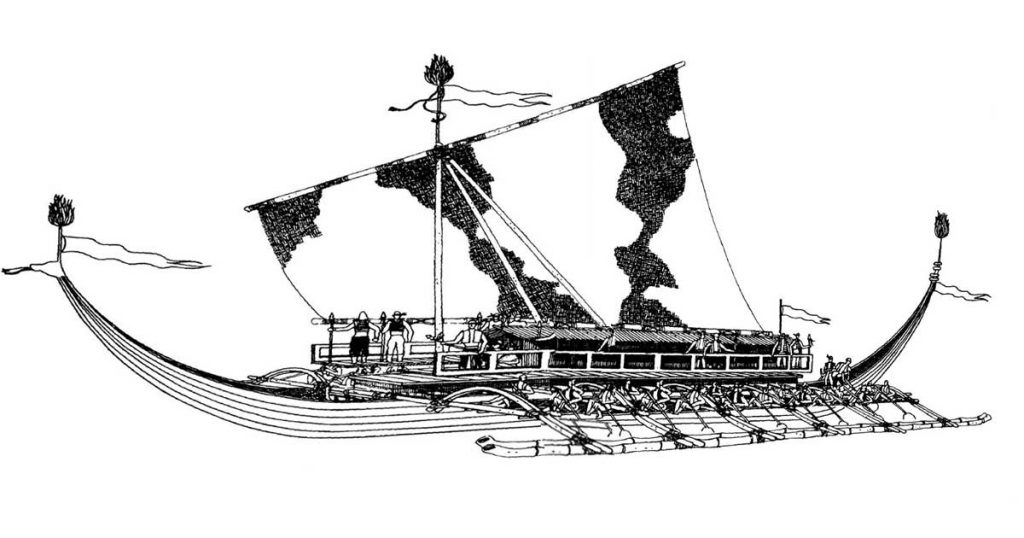

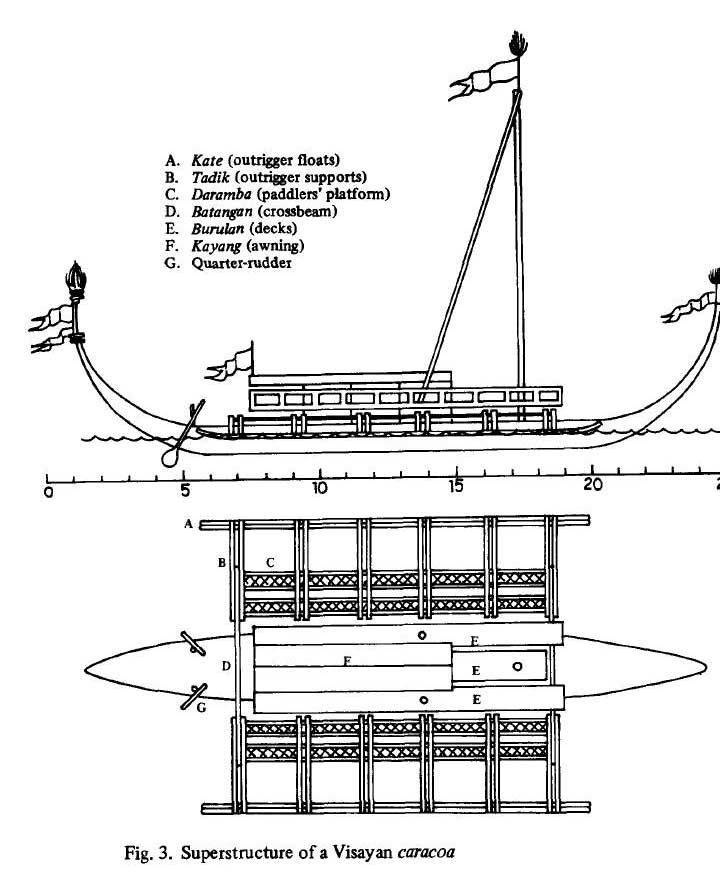

By the time of the European arrival in Southeast Asia in the sixteenth century, the plank-built boat had been developed into a highly refined man-o-war, nicely adjusted to the tools, techniques, and materials available, and local political and commercial needs. They were called korakora in Indonesia, but karakoas by the Spaniards in the Philippines. They were sleek, double-ended warships of low freeboard and light draft with a keel in one continuous curve, steered by quarter rudders, and carrying one or more tripod masts mounting a square sail of matting on yards both above and below, with double outriggers on which multiple banks of paddlers could provide speed for battle conditions, and a raised platform amidships for a warrior contingent for ship-to-ship contact. Their tripod masts and characteristic S-shaped outrigger supports show up in the ninth-century stone carvings of Borobudur, and their other features appear in Chinese, Portuguese, Italian, Dutch, Spanish and English accounts over a period of half a millenium.

Wang Ta-yuan, a medieval Chinese author, recognized the essential features of the plank-built boat – i.e., light, flexible and nailless – in Madura in the early fourteenth century. Writing at a time

when the second Butuan boat might still have been afloat, he says:

They make boats of wooden boards and fasten them with split rattan, and cotton wadding to plug up the seams. The hull is very flexible, and rides up and down on the waves, and they row them with oars made of wood, too. None of them have ever been known to break up.

Pigafetta noted the wooden dowels and bamboo outriggers in 1521, and Urdaneta gives the dimensions of the outriggers five years later: they are six meters shorter than the hull, their supports are three and a half meters long, and the inner-most row of paddlers sit about a half meter outside the hull. An Italian pilot with Villalobos in 1543 reported a ship with Negro oarsmen in the Visayas, and the anonymous account of the 1565 Legazpi expedition says of a Bornean three-master taken in Bohol, “It was a ship for sailing anyplace they wanted. ” Longer and more detailed accounts were given, in almost identical terms, by Portuguese Governor Antonio Galvano of the Moluccas in 1544, Dutch Admiral Jacob van Neck in 1598, and Mindanao missionary Francisco Combes, S.J., in 1667, while Manila Auditor Antonio de Morga’s famous 1609 Sucesos includes a shorter but perceptive description. But it was Combes’s brother of the cloth, Francisco Alcina, who recorded the most valuable description of all in his unpublished 1668 Historia de las Islas e Indios de las Bisayas – three chapters in which the construction of the plank-built warship is set down step by step by a man who had actually built some.

To the casual observer familiar with the great Chinese war junks of the Ming Dynasty or the Spanish galleons towering over the native karakoas, the plank-built man-o-war looks like a primitive and flimsy craft indeed. Its planking seems skin thin and its bamboo tripods a sorry substitute for those oaken masts which are almost symbols of strength and security in western literature. Their low freeboard and wide-spreading outriggers crowded with seamen outside the hull make them hardly recognizable as ships at all. A careful observer like Pigafetta realized that their hulls were ”very well made of boards with wooden pegs [though] above this they are nothing but very large bamboos,” but Ch’uan-chow, Superintendent of Trade Chao Ju-kua, thought they were simply bamboo rafts. Their paddles with blades like dinner plates or elephant ears show up in Chang Hsieh’s 1613 sailing directions as being “shaped like a gourd cut in half and left hollow as waterbailers.” karakoa seamanship was also inexplicable; the sailors were often in the water outside the boat. To bail out a swamped vessel, for example, they went over the side to rock it and slosh out the water with paddles; and when emergency speed was needed, the paddlers on the outrigger floats were literally in the water. Chang confuses these two actions in the following terms: “On occasion, the men with these ballers jump into the water to rock the boat and the speed is doubled.” And who could imagine that a warship could be launched by the simple manoeuver of picking it up and running into the surf with it? This outlandish detail reached the remote mainland study of scholarly Superintendent Chao to be expressed in his 1225 comment on Visayan mariners as follows:

They do not travel in boats or use oars, but only take bamboo rafts for their trips; they can fold them up like door-screens, so when hard-pressed they all pick them up and escape by swimming off with them.

But the comparisons are gratuitous. The karakoa was not designed to cross high seas in any weather before any winds, out of sight of land and provisions for months at a time, carrying heavy cargos financed by international banking houses, and even heavier artillery for slugging it out with competitors of their kind. Rather, they were intended to carry warriors at high speeds before seasonal winds through dangerous reef-filled waters with treacherous currents on interisland raids and high-profit ventures mounted by harbor princelings with limited capital. For this purpose they were superbly fitted. If a fair comparison is desired, it may be found in the Viking ships of Scandinavia. A third-century example excavated in Nydam, Schleswig-Holstein, has a double-ended hull like the Butuan finds, with one-piece strakes lashed to flexible ribs by cleat-lugs. But by the time of the later Butuan boat, the Viking ship had developed along its own line of specialization into a heavy, rigid-ribbed, deep-sea vessel capable of withstanding the buffeting of some of the roughest waters in the world – those of the North Atlantic between Europe and America. In Southeast Asia, on the other hand, specialization ran to speed and maneuverability in shallow coastal waters.

The flexible hull, curved keel, shallow draft, quarter rudders, and protective outriggers give the karakoa life-saving advantages in waters entailing a high risk of banging on coral reefs, grounding on rocky coasts, or beaching on sandy shores. The force of direct underwater blows that would stave in the hull of a rigid vessel, or at least loosen its nails, is instantly redistributed to other parts of the prestressed plank-built hull, and rattan lashing that comes loose can easily be tightened again or replaced. Nails entail a special disadvantage of their own: they loosen as they rust and induce rot into the surrounding wood in the process. Quarter rudders are actually large steering oars on one or both quarters that can be raised on a moment’s notice to avoid underwater obstructions, and outriggers effectively act as fenders against contacts at water level. Nor is the presence of the tripod mast on the plank-built hull mere coincidence. The pliant karakoa hull precludes the stepping of a tall mast into a rigid keel on which it would exert the strain of great leverage: instead, the more agile tripod can safely shift its burden with the movements within the hull itself.

Outriggers serve a half dozen distinct functions in sailing karakoas. Their most obvious purpose is to prevent rolling. They run just above the surface on a well-trimmed ship – “kissing the water,” as Morga says – and are slanted upwards at the ends to lessen water resistance. (The seventeenth-century Mindanao equivalent of keel-hauling was to tie the culprit to one of the outrigger floats.) They add the necessary buoyancy to keep a swamped vessel afloat, and missionary accounts contain grateful tales of friars being brought safely to port by Filipino crews working in water up to their necks. Outriggers receive the first force of heavy seas on the beam and, if worse comes to worst, come apart first and so give a vessel time to seek shelter before breaking up. Thus an anti-Moro task force dropped anchor off Panay in 1618 when its port outriggers began to be strained by strong northeasterly brisas. Outrigger beams also provide support for as many as four banks of paddlers for high speed in battle, and the whole outrigger structure provides the handles by which the crew picks up a karakoa for beaching and launching. (A hundred men can easily carry a five-ton vessel if they can get ahold of it.) Speed in launching was an essential feature of self defense for coastal villages exposed to raiding attacks, for boats were regularly beached high and dry at night. Encumbering and destructive marine weeds accumulate on an exposed hull in tropical waters in one or two weeks’ time, and shipworms – according to Hernando de los Rios Coronel in 1619 – could eat up the hull of a galley anchored in the Pasig River in just twelve months.

The fact that the karakoa was double-ended made it extremely maneuverable in battle: its paddlers could back it down as rapidly as drive it forward simply by turning around in their places and shifting the helm to the other end. Paddles have the advantage of giving direct control of the depth, length, and frequency of stroke – as Fr. Combes said, “Their paddling is precise because they strike directly with the paddles right in their hands without being fastened to anything. ” It is the use of paddles, of course, which requires such low freeboard. Oars permit greater length and leverage, and can generally be worked longer than paddles without tiring, though Fr. Alcina testifies that Visayans born and raised to the task can be relied on to paddle from sunrise to sunset.

The karakoa’s shallow draft makes it less responsive than deeper vessels to the vicious currents of the narrow channels and interisland passages of the Philippine archipelago which were the constant bane, and frequent undoing, of Spanish galleons. But it is a distinct disadvantage for sailing in any wind other than one dead astern – for which reason Southeast Asian trade-raiding was strictly seasonal. With no keel, center- or lee-boards, or large, deep center rudder, and very little hull beneath the water, the karakoa was easily blown sideways on a smooth sea and impeded by a choppy one. When running before the wind, its speed was proverbial – probably twelve to fifteen knots to a galleon’s five or six – and a factor in the Sulu Sultanate’s survival as an independent maritime principality until the advent of steam. But with a wind on the beam, the karakoa was already close-hauled, and it performed poorly in rough water in even a quartering wind, and could hardly tack under any conditions. Thus when Commander Morga sailed out of Mariveles Bay in October 1600 in a fresh northwester with choppy seas and headed due south to intercept Dutch Admiral Oliver van Noordt off the Batangas coast, he had to leave his two karakoas behind to cross over to Cavite inside Corregidor Island.

This same shallow draft, however, was an essential feature of the fine lines of a hull of such hydrodynamic excellence the karakoa actually planed with a following wind – that is, lifted up in the water. The common Philippine barangay shared this design, and its performance was praised in such a pleasant and informative paean by Fr. Alcina that it is worth quoting at length:

Let us say something about the speed of these ancient boats of the Visayans, which was certainly great in a barangay of one encomendero of these islands called Pedro Mendez, which – though I did not see it, I heard about it from many who embarked on it many times – was so fast that nobody in it could keep his footing when they were rowing; even though it had no more than two banks of paddlers, one on each side, it was of low freeboard and long, so they struck the water well with their paddles. It used to travel by paddling between sunrise and sunset from the town of Paranas – where many of these barangays are made, and the same Filipino expert who made them made me a little one – to the City of Cebu, where the said Pedro Mendez had his house, this being a distance of more than forty leagues between leaving the one town as the sun was rising and reaching the other before it set, which seems unbelievable since they were traveling at more than four leagues an hour, but the number of witnesses leaves no room for doubt. And I experienced practically the same thing in this little barangay which was made in the same town, for I never met another boat and made romba – which is what the Filipinos call recateado in Spain, which, for those who do not know it, is to race – that could keep up with me, and oftentimes when I was sailing near the edge of the sea or some river, I noticed that no man could keep up with me no matter how long he ran along the beach following me.

European explorers had the good sense to use native vessels from the very beginning of their invasion of Southeast Asia. The ship Magellan’s friend Francisco Serrano ran aground in 1511 had been purchased in Banda, and when Governor Gonzalo Pereira sent some Portuguese officers to threaten Legazpi in Cebu in 1567, they made the trip from Ternate in two karakoas. So, too, when Spanish Governor Acuna attacked the Dutch in that island forty years later, they escaped with their families in four joangas, a sort of king-sized karakoa. Legazpi himself used Filipino-built and Filipino-manned vessels for exploring the Visayas, and sent Martin de Goiti to Luzon with fifteen of them in 1570. Smaller craft called biroco formed part of the Spanish fleet sent to Borneo in 1579, and more of them were stationed below Manila during a Japanese threat in 1592. Morga regularly used karakoas as dispatch boats and tenders, and by 1609 they were in such common use the Spanish King was moved to order some improvement in their design to protect their overworked indio crews from inclement weather. In the seventeenth century, whole fleets of them were being built to fight fire with fire as Moro Filipinos contested Spanish control of the Visayas. All the major naval engagements joined during Sultan Kudarat’s long lifetime were fought by opposed fleets of plank-built men-~war with a thousand-year pedigree. And the six boats Captain Francisco de Atienza carried up to Marawi in pieces in 1639 and reassembled on Lake Lanao were genuine Philippine pre-fabs, too.

Hernando de los Rios Coronel once remarked that a karakoa was a boat that could be sunk with one oar of a galley. As a matter of strict fact, Spanish galleys did not often get the chance. As Fr. Combes accurately said, “The care and technique with which they build them makes their ships sail like birds, while ours are like lead in comparison.”

SOURCE: Boat-Building and Seamanship in Classic Philippine Society, William Henry Scott, Philippine Studies vol. 30, no. 3 (1982) http://www.philippinestudies.net/files/journals/1/articles/1696/public/1696-3504-1-PB.pdf

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.