THE EXAMINATION of Philippine pre-history and how that fits into the modern world is always a very fascinating and popular topic here at The Aswang Project. I’ve written about the subject of few times, and have always remained open to new ideas, opinions and concepts. I’ve had my mind changed about different theories and try to present the articles as a discussion rather than a dictation of fact. I am also presenting this article as a starting point for discussion.

A few years ago, articles began surfacing about the transgender Tagalog deity, Lakapati. As I have mentioned in previous articles, I support the evolution of deities into the modern realm. Myths, Legends, and Epics evolve over time. This is a fact. Dr. Ivie Carbon Esteban (Mindanao State University) has tracked changes to the same epic in Mindanao. Her work shows how important historical documentation is. On the opposite side, we need to acknowledge that oral literature (or folk literature) encompasses the whole of life’s experience, including cosmology and theology, in relation to their audience. We can certainly look at a specific time period and reflect on particular documentation, but there needs to be room for the arts and literature to use this aspect of culture to inspire and include the audience. With oral literature, written historical documentation should only be a reflection of the time it was documented – while considering the constraints of that documentation.

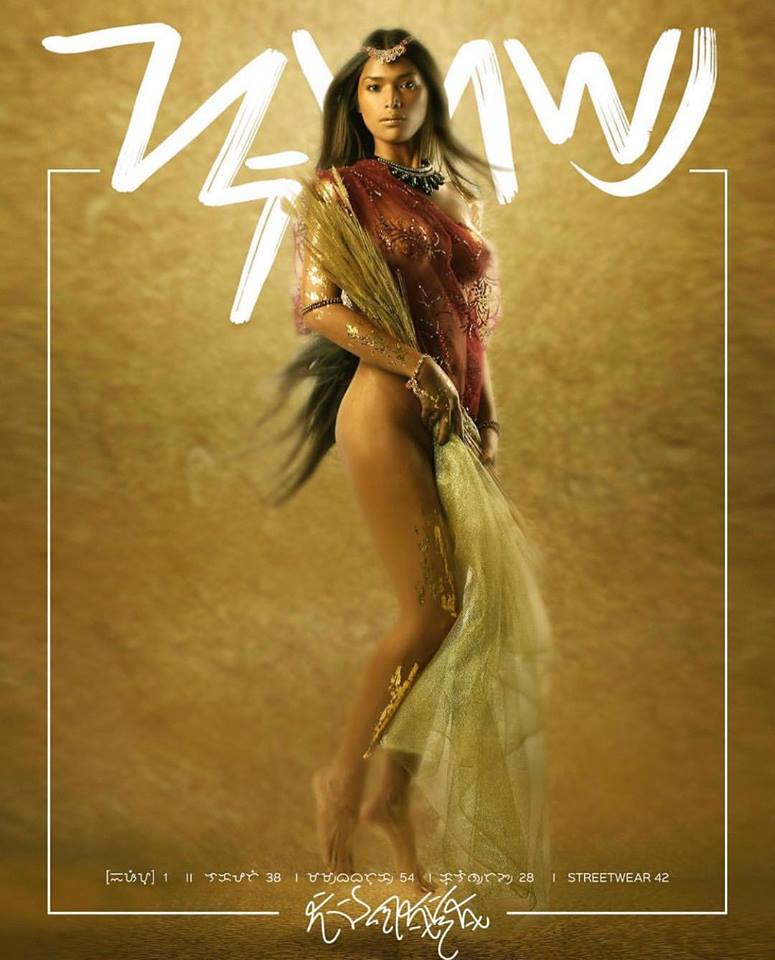

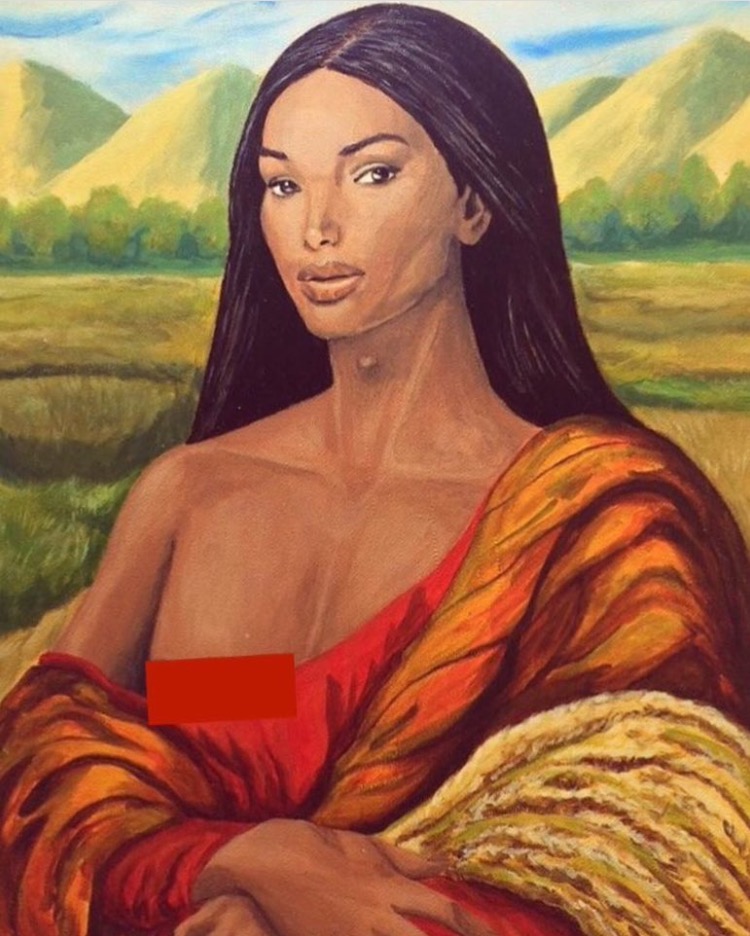

Before moving forward, I will quote Filipino creators Renz Botero, Natu Xantino and Ram Botero (Candy Darling) who used visual art to recreate queer experiences through local folklore, showcasing the range of Philippine pre-colonial culture in their vision at their exhibit called Diwata.

“Just as mythology is not historically accurate, our reimagination of pre-colonial deities transcends history to represent true experiences. It is a celebration of our boundless capacity to transform.”

Lakapati/ Ikapati, Deity of Fertility & Agriculture

The name Lakapati may come from the Tagalog word Lakan which was a title for a noble ruler – the Tagalogs version of Rajah or Datu – and Pati, which comes from Sanskrit and is also a title meaning ‘master’ or ‘lord of’.

The following historical entries are found for Lakapati.

CUSTOMS OF THE TAGALOGS (two relations). Juan de Plasencia, 1589

The idols called Lacapati and Idianale were the patrons of the cultivated lands and of husbandry.

BOXER CODEX

They have another called Lacapati. to whom they make the same sacrifices of food and words asking for water for their fields and for him to give them fish when they go fishing in the sea, saying if they do not do this, they would have no water for their field and much less would they catch any fish when they go fishing.

VOCABULARIO DE LA LENGUA TAGALA, De San Buenaventura, Pedro, O.F.M. (1613)

During rituals and offerings, known as maganito, in the fields and during the planting season farmers would hold a child up in the air while invoking Lakapati and chant directly to them, “Lakapati, pakanin mo yaring alipin mo, huwag mo gutumin.” (Translation: Lakapati, feed this servant who is yours, let them not be hungry). This chant was written down in the oldest Tagalog dictionary, Pedro de San Buenaventura’s Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala (1613), which also presented idea of Lakapati as a male/female image:

IDOLO) Lacapati (pp) era el abogado de las sementeras, figura de hombre y muger todo junto,…(Lacapati was the advocate of sowed fields, figure of man and woman all together,…)

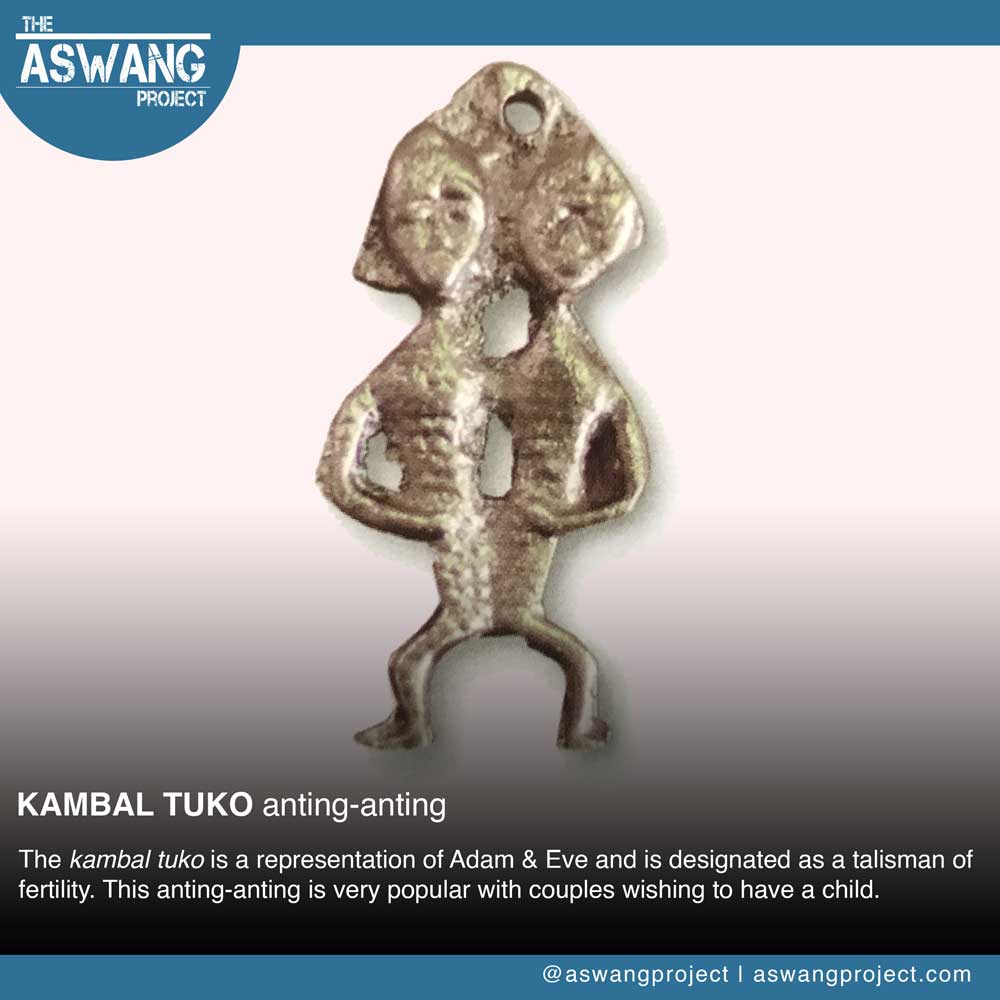

The kambal tuko (siamese twins) anting-anting is a representation of Adam & Eve and is designated as a talisman of fertility. This anting-anting is very popular with couples wishing to have a child. Some mythology enthusiasts have speculated that the kambal tuko anting-anting may be a deviation on the Lakapati fertility idol described by Buenaventura, which presented the idea of Lakapati as a male/female image.

OUTLINE OF PHILIPPINE MYTHOLOGY by F. Lanada Jocano (1969)

Ikapati, goddess of cultivated land, was the most understanding and kind among the deities of Bathala. Her gift to man was agriculture. As the benevolent giver of food and prosperity, she was respected and loved by the people. From her came fertility of fields and health of flocks and herds.

Ikapati was said to have married Mapulon, god of seasons. They had a daughter named Anagolay, who became the goddess of lost things. When Anagolay attained maidenhood, she married Dumakulem, son of Idianale and Dumangan, by whom she had two children, Apolake, who became god of the sun and patron of warriors, and Dian Masalanta, who became goddess of lovers.

BARANGAY by William Henry Scott (1994)

During sacrifices made in a new field to Lakapati, a major fertility deity, the farmer would hold up a child and say, “Lakapati, pakanin mo yaring alipin mo; huwag mong gutumin [Lakapati, feed this thy slave; let him not hunger]” (San Buenaventura 1613, 361).

Prominent among deities who received full-blown sacrifices were fertility gods. Lakapati, fittingly represented by a hermaphrodite image with both male and female parts, was worshiped in the fields at planting time; and Lakanbakod, who had gilded genitals as long as a rice stalk, was offered eels when fencing swiddens—because, they said, his were the strongest of all fences, “Linalakhan [sic] niya ang bakod nag bukid” (San Buenaventura 1613, 361).

WIKIPEDIA

The description of Lakapati in Wikipedia combined Jocano’s description of Ikapati with other historical descriptions of Lakapati.

Lakapati – The goddess of fertility and the most understanding and kind of all the deities. She was a hermaphrodite, having both male and female genitalia, symbolizing the balance of everything. Her bodily expression is notably feminine. Also known as Ikapati, She was the giver of food and prosperity. Her best gift to mankind was agriculture (cultivated fields), a reason why she is praised along with Dimangan, god of good harvest. Through her teachings, she was respected and loved by the people. She was known to be the kindest deity to the Tagalogs. Later, she married Mapulon, who courted her tirelessly. Her marriage with Mapulon was symbolic for the ancient Tagalogs as it referred to marriage as a mutual bond between two parties regardless of gender, which was common and an acceptable practice at the time. She had a daughter, named Anagolay who aided mankind when they have lost something or someone. During early Spanish rule, Lakapati was depicted as the Holy Spirit, as the people continued to revere her despite Spanish threats. In Tagalog animism, the small unhusked rice grain was Lakapati’s emblem.

This raised an important question: Are Ikapati and Lakapati different and coming from variant Tagalog belief structures? This is important because Ikapati was documented as a ‘goddess’ who went on to marry and have children, while Lakapati had previously been described as “him” or as a “figure of man and woman all together.” The popular opinion is that Jocano took liberties with his Tagalog pantheon and not everything is entirely accurate. I admit that I had fallen into this thinking because Jocano’s sources are so difficult to find. Some may accuse me of flip-flopping, but I am not. I am reframing my previous stand with new information and a presupposition that Jocano, or one of his students, discovered the information about Ikapati through fieldwork. I think it is more of a personal or professional choice to simply dismiss the work of Jocano, a very well respected anthropologist. There may not be any corroborating sources, but that can be said of almost all Spanish, American, and the early Filipino folklorists’ documentation as well. I very recently took the time to scour through Jocano’s work looking for myths or other information that he may have documented regarding Lakapati. While Jocano’s Tagalog pantheon poses a lot of questions, there are some answers when one is willing to look deeper into his research.

For instance, Amanikable was historically documented as the “idol of hunters,” yet Jocano gathered two modern legends (‘Why the Baka-Bakahan Have Scales and Horns’ & ‘The Legend of the Sea Horse’) where Aminikable is the ill-tempered ruler of the sea. One is no more correct than the other, they are simply documented at different times in history and in different locations. Mythology evolves. Who Aminikable was does not change who they became to the people. We freely state that Aminikable was the “idol of hunters” and in some modern myths, the “ill-tempered ruler of the sea.” Why won’t we do the same for Lakapati?

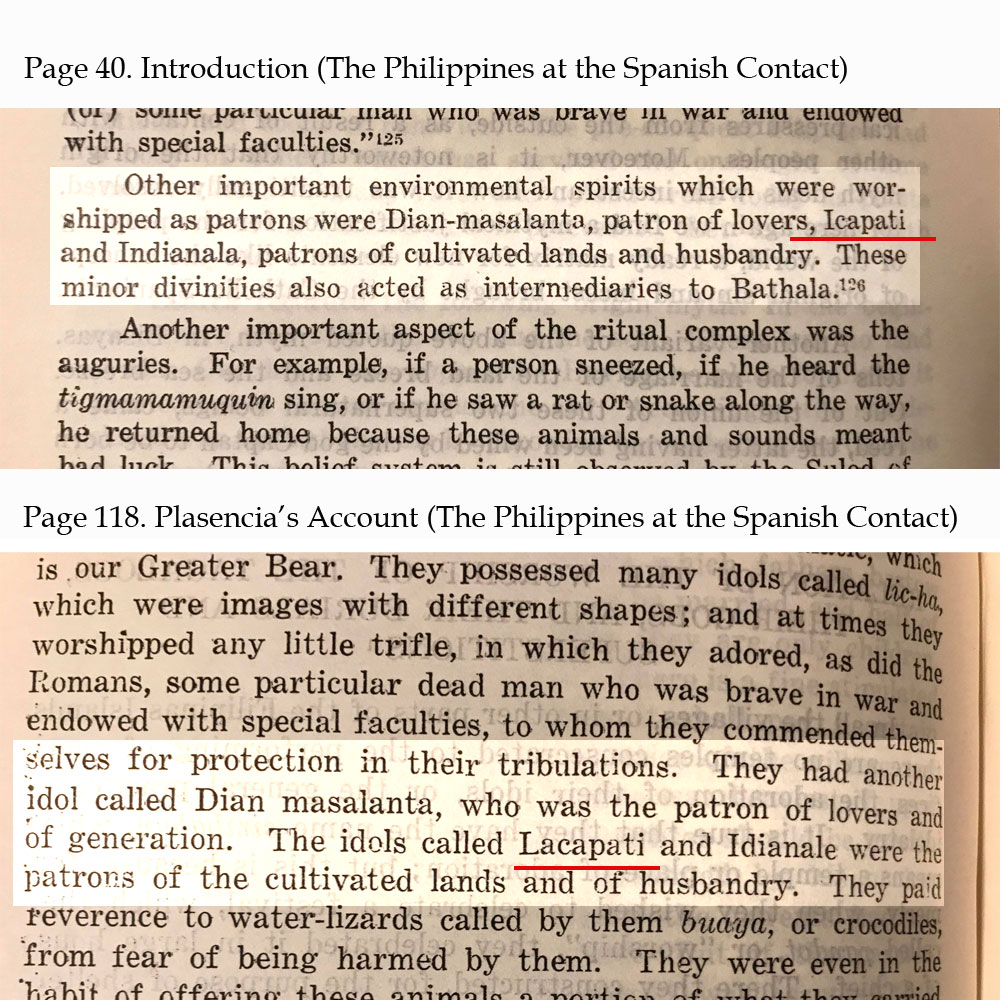

Unfortunately no myths on Lakapati can yet be found, but last month I saw that in one of Jocano’s books (‘The Philippines at the Spanish Contact’) he quoted Plasencia’s documentation from 1589 and changed the name “Lacapati” to “Icapati”. Later in the same book, he quoted Plasencia correctly with “Lacapati”. How Ikapati gained a husband and children may remain a mystery, but there is no denying the impact his entry has had on the modern interpretations. What seems clear, is that Jocano was definitely referring to Lacapati when he wrote his entry on Ikapati.

Variants over time and location are not uncommon in Philippine Mythologies. In the Visayan pantheons, Maguayan, goddess of the underworld and sea, is sometimes referred to as the wife of the sky god, Kaptan. Other versions from areas of Cebu say Maguayan is the brother of Kaptan. Namtogan was recently documented in an Ifugao myth as the only indigenous Filipino divinity with a physical disability. Yet previous Ifugao myths only state Namtogan as a village where previous myths took place.

In Conclusion

Lakapti has been historically documented, perhaps incorrectly, as male, being a “figure of man and woman all together,” and most recently as a goddess who married and had children. I had previously left this article open – essentially inviting people to assist in establishing Lakapti had a husband and children. Since it is now absolutely clear that Jocano’s entry on Icapati was meant to mean Lakapti, it boils down to one’s esteem for F. Landa Jocano and the value placed on his entry. He was certainly familiar with the previous documentation. I admit that is easy to dismiss such things when Jocano did not provide sources. Still, Jocano was the first to uncover the Hinilawod epic of Panay. I wonder if that would also have been deemed fictional had Alicia Magos, and others, not gone in and validated it. I personally uncovered an undocumented legend of Bakunawa and undocumented stories of the Biangonan while spending time with the Batak tribe of Palawan. Perhaps the real issue is the lack of funding for field research. If I can bumble into a village and find these stories, there are undoubtedly thousands more to discover.

Lakapati was first documented as possibly male. ( Boxer Codex, 1590)

Then as a “figure of man and woman all together.” (Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, 1613)

Then as a goddess who married and had children. (Outline of Philippine Mythology, 1969)

Just like Aminikable, who Lakapati was does not change who they became to the people. Please don’t counter with biological constraints. These don’t apply to deities. Zeus turned a pregnant Metis into a fly and swallowed her. Suffering from a headache, Zeus asked Hephaestus to hit his head with an axe; as soon as his head was opened, Athena jumped out fully grown and clad in armour. Try to ‘biology’ that!

While modern interpretations of Lakapati, and even Namtogan, do not have the benefit of being drilled into history by the Spanish plagiarizing each others work every 50 years, they exist. The historical entries will always be there for people to explore and we can respect Lakapati for who she has become and for the reasons she means so much to some people today. Yes, some deliberately try to spread false information, but this is more a reflection on that individual’s integrity, rather than the social movement it supposedly represents. True integrity cannot be motivated by self-promotion. We would all do well to remember that.

Sources:

Blair & Roberson Vol VII, Customs of the Tagalogs (two relations). Juan de Plasencia, 1589, p178

Boxer Codex (1590), Transcribed and Edited by DONOSO, Isaac, Vibal Foundation, 2018, p. 67

Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, De San Buenaventura, Pedro, O.F.M. (1613)

Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. W.H. Scott, Ateneo de Manila University Press. 1994 p. 234

Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano, 1969, Centro Escolar University Research and Development Center

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.