In this article, I explore the documentation regarding likha. There seems to be some differing opinions on whether the term was given to ancestor and deity idols, or if it was a misunderstanding from the Spanish. The modern consensus is that the term was meant to mean ‘created image’ of an anito (ancestor spirit). Subsequently, the term likha (idol) has been disappearing from new documentation in favour of the more generally used anito. Below I hope to establish that likha could have been the term used for certain idols in some Tagalog areas and to present a hypothesis on what it may have meant. Undoubtedly, idols used by the early Tagalogs would have been as numerous as those of their northern neighbours, where the Bul’ul idols number the amount of any well-wish one may hope for themselves or the community.

According to Ferdinand Blumentritt in his DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS, the term likha. (In the usual Spanish transcription: licha) was the word used by the early Tagalog people for the idols they made in memory of their ancestors.

In modern Tagalog likha means ‘to create’.

Background

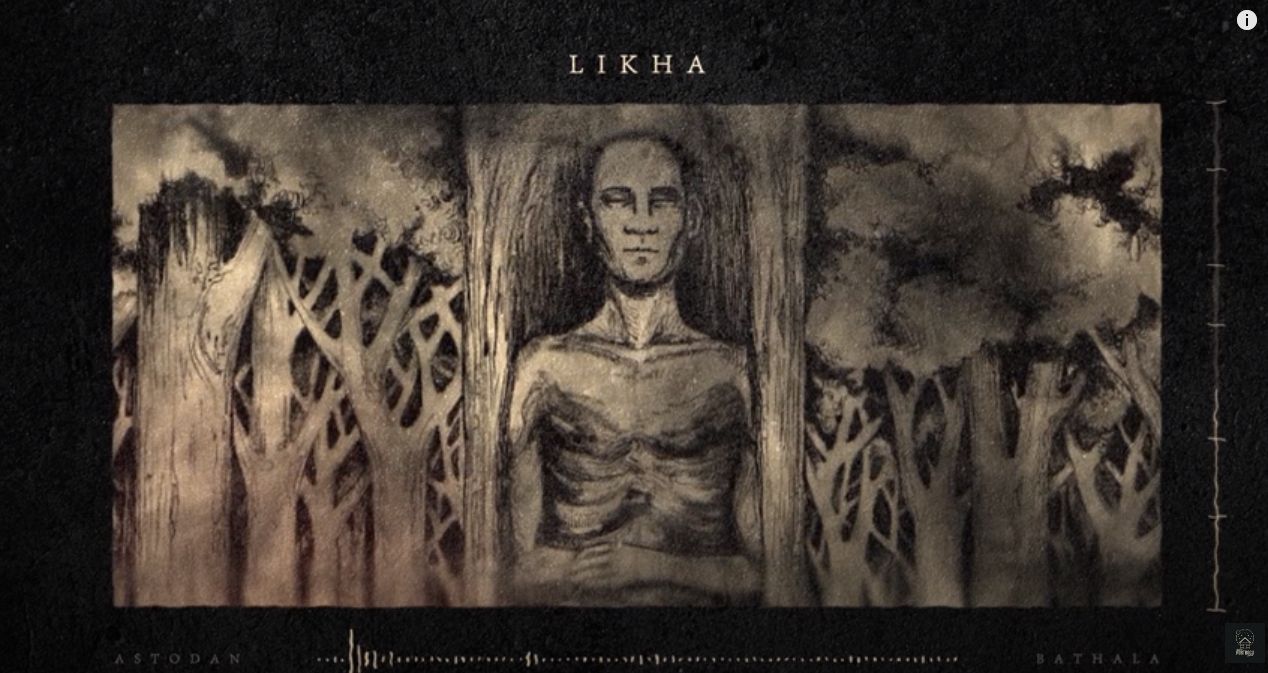

Back in early 2020 a post-rock instrumental band from Brussels called Astodan released an album that drew influence from precolonial Tagalog burial rites. It is titled Bathala and the track listing is 1. Hukluban, 2. Katalonan , 3. Likha , 4. Buaya , 5. Alay , 6. Maca Kasanaan

During an interview with Filipino podcasters they were politely asked about the song “Likha” where the interviewers stated that they thought the word meant “to create” and was probably misinterpreted by the Spanish to mean idol. This always bothered me a bit, but I had other research on the go at the time. The Spanish were by no means the most proficient curators of Philippine culture, but I was almost certain it may not have been a complete misunderstanding.

This again came up while I was reading Paths of Origin: The Austronesian Heritage [Benitez-Johannot, Purissima] where it was implied that the term likha meant “created image”. In Spanish documentation the term larawan has been used in tandem with licha. It appears that in this context, the meaning for larawan has not changed over time. In modern Tagalog, larawan means [noun] picture; illustration; painting; photograph; image; portrait.

In my opinion, it seems unlikely that there would be a misinterpretation or discrepancy for one term and not the other.

Historical Entries

There are five main historical entries found regarding the likha image in the Philippines.

Cavendish, the English navigator, who visited the Philippines in 1588, states: “These people wholly worship the Devil, who appears unto them in divers horrible forms, and they worship him by making figures of these forms, which they keep in caverns and special houses, offering to them perfumes and food, and calling them anito or licha.”

Relación de las Islas Filipinas. The Philippines in 1600. By Pedro Chirino mentions, They had their houses full of wood and stone idols, which they called Tao-tao and Lichac, for temples they had none. And they said that when one of their parents or children died the soul entered into one of these idols, and for this they reverenced them and begged of them life, health, and riches.

San Buenaventura’s Vocabulario de la lengua tagala (1613) has the following entry:

idolo. licha pc: cualquiera figura del, a este le ponen cadenas de oro, y otras cosas por adorno, destos tenian muchos y de muchos nombres algunos porne [?] aqui.

roughly: idolo. licha noun: any figure of the, to this one they put him/her chains of gold, and other things for adornment, from those they had many and of many names some put in here (in the document).

Ethnological description of the Filipinos Native races and their customs by Francisco Colin, S.J.; Madrid, 1663 says: In memory of their ancestors they kept certain very small and very badly made idols of stone, wood, gold, or ivory, called licha or laravan.

By 1738, the definition of likha began to change in the Spanish documentation. Juan Francisco de San Antonio, O.S.F. writes, “Besides these they had other idols, which the Visayans called Diuata, and the Tagálogs, Anito, each of which had its special object and purpose. For there was one anito for the mountains and open country; another for the sowed fields; others for the sea and rivers; another for the house of their dwelling. These anitos they invoked in their work, according to the functions of each one. Among these they also made anitos of their ancestors, and to these was due the first adoration of all. The memory of this anito is not even yet erased. They kept some small badly-made figures of all these, of gold, stone, ivory, or wood; and they called them Lic-hà or Laràuan, which means a “figure” or “image” among them.”

As mentioned previously, many people studying these idols from the past are content to refer to likha as a “created image”. This very loosely satisfies the definition in the Spanish documents as well as the modern use of the word.

‘Cause you know sometimes words have two meanings.

In the English language, a homophone is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A homophone may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, as in rose (flower) and rose (past tense of rise), or differently, as in rain, reign, and rein. These also exist in Tagalog, although many times the inflection differentiates the meaning, which would sometimes be lost in the Spanish documentation. Some examples would be puno (tree) and puno (full), or mahal (love) and mahal (expensive) etc.

There is a famous Chinese homophonous novelette that consists of 600 homophonic Chinese characters that are all of the same pronunciation (but some are at different inflections). So it should be no surprise that Sankrit also has homonyms.

Most modern language dictionaries from India have an entry similar to this: lēkha (लेख).—m (S) A writing; a thing written; an epistle, a bill, a document.

Purana and Itihasa (epic history) hold a different meaning for the word.

Source: archive.org: Puranic Encyclopedia

Lekha (लेख).—A deva-gaṇa (set of celestial beings) of Raivata Manvantara.

Source: Cologne Digital Sanskrit Dictionaries: The Purana Index

1a) Lekha (लेख).—Eight groups of Gods of the Cākṣuṣa epoch.

1b) A class of Pitṛs propitiated on every New Moon day. The Pitris (Sanskrit: पितृ, the fathers), are the spirits of the departed ancestors in Hindu culture.

In the Vedas, the sacred scriptures of ancient India, the “fathers” were considered to be immortal like the gods and to share in the sacrifice, though they received different offerings. The “way of the fathers,” which leads to rebirth (samsara) and is characterized by observance of the traditional duties of sacrifice, charity, and the practice of austerities, came to be distinguished from the “way of the gods,” which was a way of faith directed toward the goal of liberation (moksha) from rebirth.

We know that hindu epics, such as the Ramayana, have been interpreted into Philippine cultures as well as a myriad of loan words and cultural practices. These may have come from The Puranas, notably consisting of narratives of the history of the universe from creation to destruction, genealogies of kings, heroes, sages, and demigods, and descriptions of Hindu cosmology, philosophy, and geography. This is where Lekha (लेख) may have come from.

Conclusion

I propose that the term likha may have once represented a specific kind of idol. Perhaps the anito for which the idol was made was more prominent, older, or somehow in different standing and reverence – such as the Pitrs mentioned above. The term likha could have collectively represented a class of anito who had been designated as a minor deity in a local area – “the fathers”. It could also have been the term the Tagalogs used for idols that represented their celestial deities as suggested in the Puranas.

If we examine the above Spanish documentation with this understanding, the entries tend to make more sense. What remains of most interest to me, is that earlier Tagalogs always seemed to have two distinct terms to describe the idols representing their anitos. I present the following meanings (as admitted conjecture), while incorporating more of a puranic interpretation of likha.

Cavendish (1588)

anito (ancestor spirits) or licha (deities)

Chirino (1600)

Tao-tao (idol for ancestor anito) and Lichac (idol for deities)

Colin (1663)

Licha (idol for deities) or laravan (image of ancestor)

After almost 200 years of Spanish colonization, I believe that the term likha could have begun to lose its intended meaning in the puranic sense.

San Antonio (1738)

Lic-hà (idol for deities) or Laràuan (image of ancestor)

While I will certainly grant that it is within the realm of possibility that early chroniclers have continually misinterpreted the meaning of likha, I also know with certainty that the Spanish chroniclers did not put enough emphasis or understanding on the Hindu or sankrit influence in the Tagalog language or the Philippines as a whole. Again, I present this as a hypothesis and not as proven fact. This exercise is purely an attempt to make sense of the earlier documentation of likha.

As T H Pardo de Tavera so eloquently said in El Sanscrito en la langua Tagalag (1887) “It is impossible to believe that the Hindus, if they came only as merchants, however great their number, would have impressed themselves in such a way as to give to these islanders, the Philippines, the number and the kind of words, which they did give. These names of dignitaries, of caciques, of high functionaries of the court, of noble ladies, indicate that these high positions, with names of Sanskrit origin, were occupied at one time by men, who spoke that language. The words of similar origin, for objects of war, fortresses and battle songs, for designating objects of religious beliefs, for superstitions, emotions, feelings, industrial and farming activities, show us clearly that the warfare, religion, literature, industry and agriculture were at once time in the hands of the Hindus and that this race was effectively dominant in the Philippines.”

DNA studies are also beginning to show Pardo’s statement to be true.

As people try to rebuild the lost beliefs of the past, I think it is important to re-examine the existing information and if there is an opportunity to hypothesize a different (or deeper) meaning, it should be presented.

As always, I welcome comments and feedback over at THE ASWANG PROJECT Facebook and Instagram pages.

ALSO READ: INDIANIZED KINGDOMS | Understanding Philippine Mythology (Part 2 Of 3)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.