MAGNINDAN / MAGINDANG was, in Bicolano Mythology, the protector of fisherfolk. The below myth involved this revered deity and is meant to explain the name of barangay Nahapunan in Bicol. Nahapunan is in the municipality of Bacacay, in the province of Albay.

Bicol Mythology generally gets a blanket application, but it is almost certain that there were regional variations as is found in Visayan, Tagalog, and other belief structures throughout Luzon. I find the myth below, regarding Magnindan (named as Magindang by Realubit in Bikols of the Philippines, 1983) particularly interesting because it gives insight and confirmation for the rituals of ancient Bicolanos in the region of Bacacay.

As other Bicol myths tell us, the moon was very important. One needs only to look at myths regarding Bakunawa, the moon deity Bulan, and the Haliya rituals to see this. We know there is a practice in Leyte and also in Samar that the one who starts harvesting must see to it that it is either on a day of “Cabog – os ” —full moon , “ Guimata ” —first quarter of the moon , or “Maghi – abot ” —moon rise at sunset . The myth below shows that Bicolanos also used the moon to gauge their yields of fish, “this was then during the guimata (period of time around the new moon phase). But when otong came (during the quarter phase), there was little fish to be had.” It was then, they determined that a ritual must be performed for the deity, Magnindan.

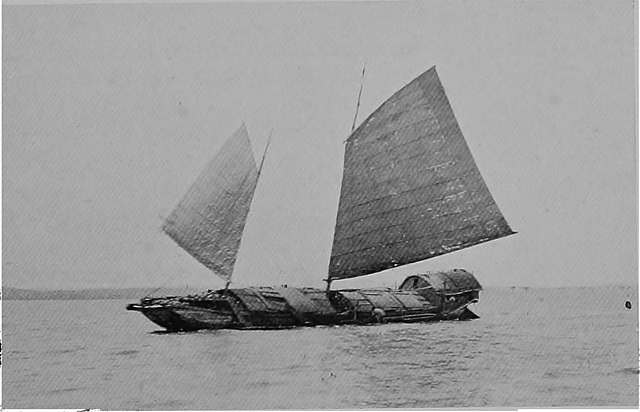

The below myth also provides amazing insight into the Magnindan ceremony itself. The villagers of Nahapunan (which remains an agricultural and seafood producer to this day) would ride into the sea on their casco (flat-bottomed square-ended barge), and throw stones and small shredded river fish into the ocean. While doing this, they would bang the sides of the boat to bring the deity’s attention to their offering. They could perform this at any time except for naniron siron (twilight) for that was when the deity rested.

NAHAPONAN, A Bicol Myth

MAGNINDAN was a beloved god of the Bicols, for did he not give them abundance of fish? He was the protector of the fishermen and it was to him that they prayed when there was little catch with either the nets or the lines. This was how their relation became closer and closer.

For years there was no cause of quarrel between Magnindan and the fishermen; and fish was plentiful. The people were prosperous.

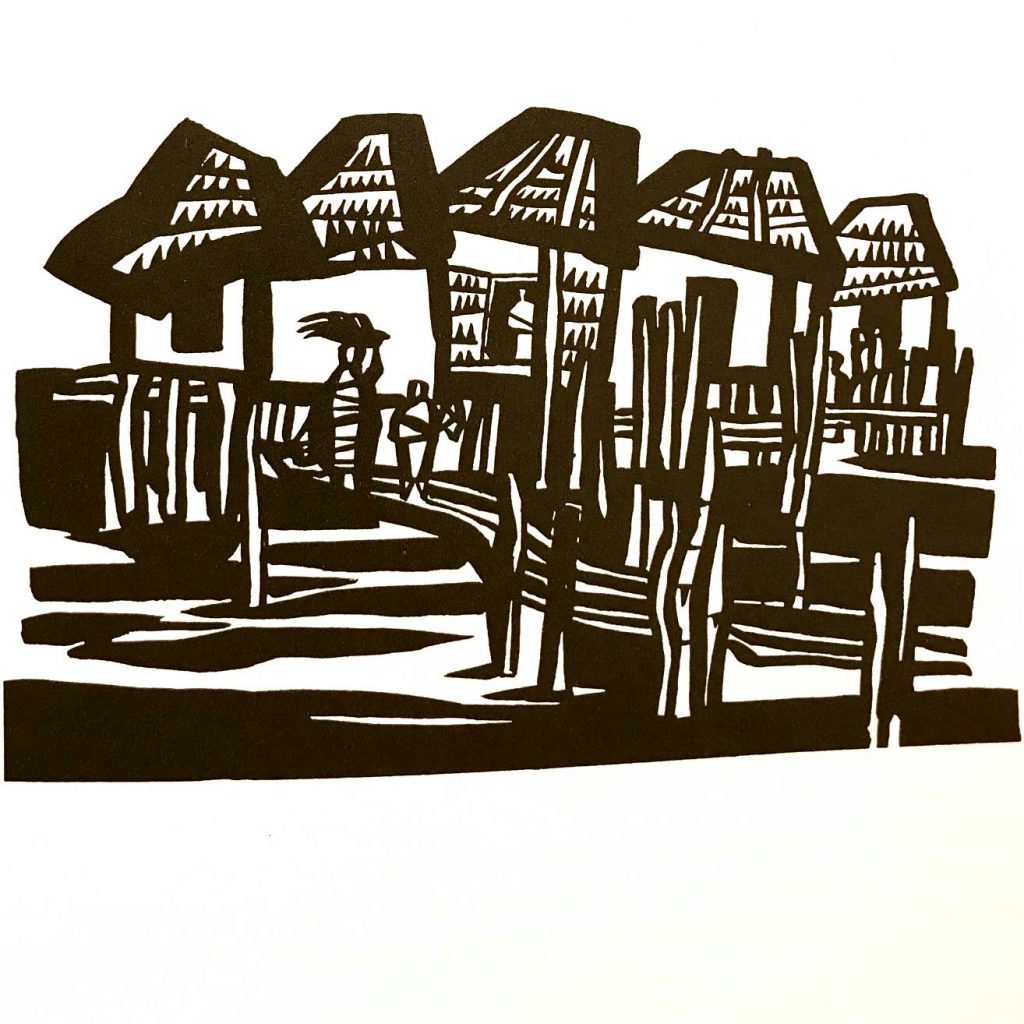

But one day into the peaceful fishing village or barrio of Bacacay came two men who were attracted by the reputed wealth of the inhabitants gained through fishing. The villagers, who could easily notice strangers among them as they were not used to them, became suspicious and asked them for their names.

The tall wily figure who apparently was the leader of the two answered: “I am Pasacat, a fisherman of Tabaco, attracted by your lucky shores. This is my helper, Maluya.” Maluya was a weak-willed youth according to his appearance but strong as well as agile in muscles.

The headman of the village conferred whether or not they would admit the two fishermen from a neighboring place.

A bright-headed old man said, “If we permit them to fish, and if Magnindan does not like them, he would in time let them know.” It was agreed that it was really a bright idea. So Pasacat and Maluya were permitted to fish in Bacacay waters.

But before leaving for the sea they were admonished not to displease the god of the fishes or else something bad might happen to them. The two did not answer. When they were ploughing the sea Pasacat asked: “What was that god they were talking about not displeasing?”

“Well, I do not know myself,” answered the younger one. “But I know that in the forest where I came from there is also a god called Ocot, the god of chase. Perhaps this god of fishes has also the power to increase or decrease the number of fishes, depending upon his will. It is very much better if we don’t offend him,” added Maluya.

“I don’t believe in it,” said the older man as if boasting. “Oh!” the other was horrified terribly. “Don’t think of that! I know several people in the forest whom I know turned to stone for disobeying the rules of the god.”

“I lead a charmed life, why should I be afraid?” said Pasacat.

“But I am afraid,” Maluya said.

“Why should you be? There is nothing alarming.” With that the discussion came to an end as they felt a nibble from one of their lines. In time they were assimilated into the barrio. The simple folks marveled at their unusual skill in their catch. Overnight they became rich. This was then during the guimata (period of time around the new moon phase). But when otong came (during the quarter phase), there was little fish to be had. Pasacat and Maluya wondered at this. They asked the villagers, and they learned that they must entreat Magnindan to give them more fish.

The villagers themselves put out to sea to make the necessary ceremony to call for more fish. They brought with them stones and shredded small fish that they had caught in the rivers. On reaching the designated spot for the ceremony, they pounded the sides of the casco on which they were riding and kept pounding throughout the whole sacrifice. The sound was made to call the attention of Magnindan. Then the other members of the party threw the shredded fish, and still the others threw the stones into the sea. After that they were happy, for fish came abundantly again.

This ceremony, however, had one limitation, that is, it could be performed at any time of the day except during twilight (naniron siron). For the people said that Magnindan was sleeping then and hated to be awakened by their prayers. This the people obeyed without any complaint and they learned to conform to that.

The two strangers used this sacrifice to advantage. They now commanded the local market and they had already raised the price of fish. This the people resented. And soon the presence of the two strangers became very obnoxious.

Time passed on. The guimata was coming again, and then the otong. And there was little fish. And the village did not cry for fish, for they were afraid that only the two strangers would catch all the fish. Pasacat and Maluya, however, set about to make an offering to the fish god. They started in the morning and continued it till noon and afternoon. They were mad with delight, for they had not more fish than desired, which they could sell to the villagers at profitable prices.

So with madness, they continued the sacrifice till twilight and kept imploring the god to give them more fish. Magnindan, on being awakened by the noise above him, was terribly angry, and summoned an attendant to see who it was that was making the noise. The helper went out, returned, and reported who it was.

“Is this my reward? I have given them more fish than the villagers. Ungrateful!” Magnindan swore to punish them. He ordered all the fishes of the sea to retire to their caverns. Pasacat swore seeing the fish was not forthcoming. This made the fish god all the more angry. Then he caused a storm.

Maluya cried, “Sir, the god is angry!”

“Weak heart! What god?” scorned Pasacat.

The storm grew and the waves swelled. The two fishermen decided to sail homeward. But when they tried to lift their anchor it would not move an inch from the bottom. All night and morning the next day they could not break away from there. The people on the shore were glad the two extortionists were being punished by a just god. Pasacat and Maluya became sick of it all.

Toward twilight they were still chained there. Then just as the sun set that day there was a huge flash of lightning (linti) followed by thunder (dalogdog). After this the air became calm and the moon rose. The villagers looked out to find out what had become of the two men. They saw them bending on their casco and looking down. They did not mind them then. But as days passed and the two did not leave the place they became curious. And they put out to sea to find out. To their great horror they discovered that the two men had been turned to black stones. And they were standing on coral beds where before there was none. The living men looked at each other knowingly.

To this day these figures, now unrecognizable as human forms, can still be seen near Bacacay Beach. The place is called nahaponan because it was there that the afternoon (hapon) ended them (twilight).

SOURCES: Eugenio, Damiana. Philippine Folk Literature: The Myths. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press. 2010

Realubit, M. L. F. Bikols of the Philippines. A.M.S. Press. 1983

Folklore Studies Vol. 15-17. The University of Michigan. 1956

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.