The Manobo are several people groups who inhabit the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. They speak one of the languages belonging to the Manobo language family. Their origins can be traced back to the early Austronesian peoples who came from the surrounding islands of Southeast Asia. Today, their common cultural language and Austronesian heritage help to keep them connected.

The Manobo cluster includes eight groups: the Cotabato Manobo, Agusan Manobo, Dibabawon Manobo, Matig Salug Manobo, Sarangani Manobo, Manobo of Western Bukidnon, Obo Manobo, and Tagabawa Manobo. The groups are often connected by name with either political divisions or landforms. The Bukidnons, for example, are located in a province of the same name. The Agusans, who live near the Agusan River Valley, are named according to their location.

The eight Manobo groups are all very similar, differing only in language and in some aspects of culture. The distinctions have resulted from their geographical separation.

The contents of this article have been taken from the 1931 memoir THE MANÓBOS OF MINDANÁO by John M. Garvan, and may not accurately reflect the beliefs of the modern people representing the Manobo language group. Beliefs among Manobo language groups can vary significantly from region to region. For instance, if one were to look at the religion and beliefs of the Obo Manobo people around Mt. Apo (see: A voice from Mt. Apo, Melchor Bayawan, Linguistic Society of the Philippines, 2005) it would be almost unrecognizable in comparison to the contents of this article. The bulk of the research in this study was conducted at the beginning of the 20th century and appears to have been gathered primarily in Upper Agusan and the Agusan Valley. In 1908, as Catholicism spread, Eastern Mindanao was part of a vast religious movement – the Tungud movement – so these historical studies are very helpful benchmarks in the evolution of early tradition. Since these are living beliefs, they have continued to evolve over the last one hundred years. Comparisons have been made with the modern practices of the Matigsalug-Manobo, particularly the practice of pang-o-tub tattooing.

When you read “I” or any other similar subjective or nominative pronoun in the following text, it is referring to John M. Garvan. The word “mutilation” has been replaced with “modification” and an outdated term has been changed to “a man who might identify as a woman.” Any additional comments from myself has been added in parenthesis as a (note).

_______________________________________________

BODY MODIFICATIONS

GENERAL REMARKS

The purpose of most body modifications among the Manóbos is ornamentation. The one exception is circumcision which will be discussed later.

Scarification is nowhere practiced in eastern Mindanáo except among the Mamánuas. In 1905 I came in contact with several Mamánuas of the upper Tágo River (within the jurisdiction of Tándag, Province of Surigáo) and noticed that they had cicatrices on the breast and arms. I concluded that the scars were due to the practice of scarification. Inquiries since that time made among both Manóbos and Bisáyas have confirmed these conclusions. Head deformation is not practiced in eastern Mindanáo.

No painting of the body is resorted to other than the blackening of the lips with soot. To effect this a pot is taken from the fireplace and the bottom of it is dexterously passed across the lips, leaving a black coating that, with the fluid from the chewing quid made up of tobacco, lime, and máu-mau frequently becomes permanent till moistened by drinking. It is a strange sight to see a handsome Manóbo belle, decked out with beads and bells, or a dapper Manóbo dandy, take the olla, and darken the lips.

No religious or magic significance is attributed to any of the following modifications, nor are any religious or other celebrations performed in connection with them.

MODIFICATION OF THE TEETH11

11Há-sa-to-únto.

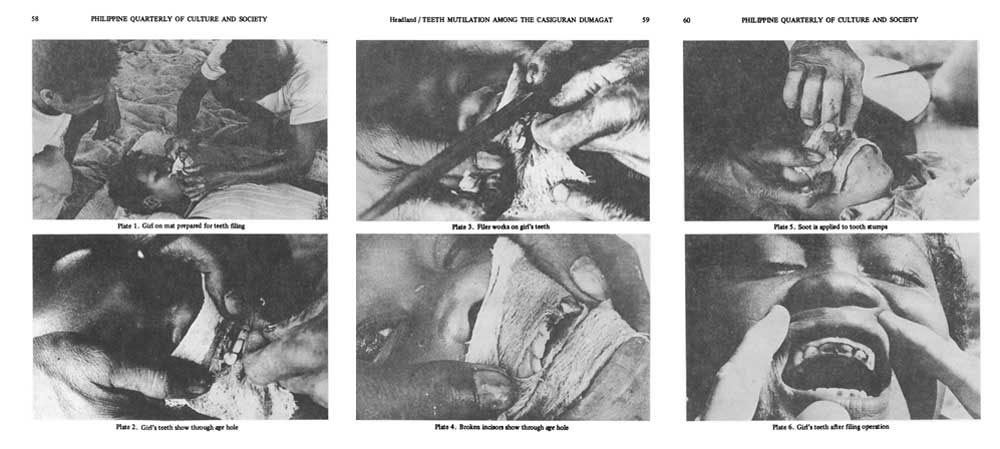

As the age of puberty approaches, both boys and girls have their teeth ground. The process is very simple but extremely painful, so much so that the operation can not be completed at one sitting. I think, however, that the painfulness of the process depends on the quality of the stone used, for the Mandáyas of the upper Karága River claim that there is a species of stone that does not cause much pain.

A piece of wood is inserted between the teeth to keep them apart. The operator, usually the father, then inserts a small flat piece of sandstone, such as is used for sharpening bolos, into the mouth and with a moderate motion grinds the upper and lower incisors to the gums. It is only the difficulty of reaching the molars that saves them, as the writer was informed. In all, 10 front teeth disappear, and a portion of 4 others. After filing, the teeth of the upper jaw appear convex and those of the lower, concave.

I estimate the minimum time necessary to grind the teeth to be from 3 to 6 hours, spread over a period varying from 3 to 10 days.

(note: the images below are from the article “TEETH MUTILATION AMONG THE CASIGURAN DUMAGAT”. The Dumagat people are an Aeta group on Luzon. It is hypothesized that they got this tradition from the Ilongot people)

The patient displays more or less evidence of pain, according to his powers of endurance but is continually exhorted to be patient so that his mouth will not look like a dog’s. This is the reason universally asserted for their objection to white, sharp teeth: “They look like a dog’s.”

After each grinding, the subject experiences sensitiveness in the gums and can not masticate hard food. When this sensitiveness is no longer felt, usually the following day, the grinding is resumed.

Blackening of the teeth is effected principally by the use of a plant called máu-mau (note: most likely most likely E. pinnatum) which, besides being used as a narcotic, has the property of giving the teeth a rather black appearance. After being chewed, it is rubbed across the teeth. The juice of the skin is expressed into a quid of tobacco mixed with lime and pot black, the whole forming the inseparable companion of the Manóbo man, woman, and even child. It is a compound about the size of a small marble and is carried, until it loses its strength and flavor, between the upper lip and the upper gum, but projecting forward between the lips.

It is to be noted here that the primary object in the use of this combination is not the discoloration of the teeth. The compound is used mainly for the stimulating effects it produces, the pot-black being added as an ingredient in order to blacken the lips and so improve the personal appearance of the user of it. The quid is frequently carried behind the ear when circumstances require the use of the mouth for other purposes.

Another means that helps to stain the teeth is the constant use of betel nut and betel leaf mixed with lime, and, in certain localities, with tobacco.

(note: below is a 10 minute video with members of the B’laan group in Mindanao showcasing and explaining what should be considered beautiful.)

MODIFICATION OF THE EAR LOBES

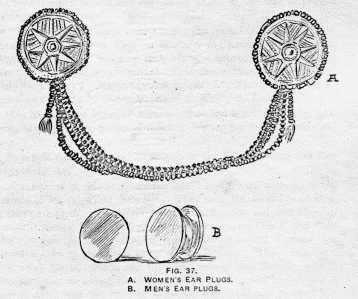

The practice of mutilating the ear lobes12 is universal and is not confined to either sex. It consists in piercing the ear lobes in one, two, or three places. This is done usually at an early age, with a needle. A thread of abaká fiber is then inserted and prevented from coining out by putting a tiny pellet of beeswax at each end. As soon as the wound heals, the perforation is enlarged in the case of a woman in the following manner: Small pieces of the rib of the rattan leaf are inserted at intervals of a couple of days until the hole is opened enough to receive larger pieces. When it has expanded sufficiently, a small spiral of grass, usually of pandanus13 is inserted. This, by its natural tendency to expand, increases the size of the aperture until a larger spiral can be inserted.

12Ti-dáng.

13Bá-ui (Bisáya, ba-ló-oi).

PHOTO: Karla Rimban and Billy Chavez/Alyx Ayn Arumpac/CM, GMA News

The opening is considered of sufficient size and beauty when it is about 2.5 centimeters in diameter. In addition to this large aperture, which is located on the lower part of the lobulus, there may be two other small perforations about 1.5 centimeters further up. These latter serve both in men and women for the attachment of small buttons, while the former is confined exclusively to women and serves for the insertion of ornamental ear disks.

DEPILATION

A beardless face is considered a thing of beauty, so that a systematic and constant eradication of the face hair is carried on by the Manóbo from the first moment that hair begins to appear upon his face. For this purpose he often has a pair of tweezers,14 ordinarily made out of beaten brass wire, with which he systematically plucks out such straggling hairs as he may find upon his upper lip and on the chin, as well as the axillary hair. The pubic hair is not always eradicated. A small knife15 is frequently employed as a razor, not only on the chin and upper lip but also for shaving the eyebrows. The removal of the last mentioned is a universal practice, for hair on the eyebrows is considered very ungraceful. Hence both sexes shave the eyebrows, leaving only a pencil line, or, in some districts, not even a trace of hair.

14Pan-úm-pa’.

15Called ba-di’ or kám-pit.

The hair on other parts of the body is not abundant and it is not customary to remove it.

TATTOOING16

After making an infinity of inquiries, I learned that tattooing is merely for the purpose of ornamentation. By a few I was given to understand that under the Spanish regime, when killing and capturing was rife, the tattooing was for the purpose of the identification of a captive. It was customary to change the name of a captive, and as he was sold and resold, the only way to identify him was by his tattoo marks.

Be that as it may, the practice seems to have at present no further significance than that of ornamentation. No therapeutic nor magical nor ceremonial effects are associated with it. Neither is it symbolic of prowess, nor distinctive of family, place, nor person, for two persons from different localities and groups may have the same designs.

(note: In a 2012 article on the practice on Pang o tub among the Matigsalug-Manobos, it was stated the tradition has existed for thousands of years. Tattoos serve as an identifying mark of the tribe. “Kapag may tato ka, ibig sabihin totoong katutubo ka,” said tribe leader Datu Antayan Baguio. Before tattooing, the leaders say a little prayer to Manama, the God of the Matigsalug-Manobos. The Manobo tattoos’ significance and purpose also go beyond the physical world. They believe that one’s tattoo serves as a guiding light in the afterlife. “Kapag namatay ka, madilim ang lahat. ‘Yung tattoo, parang ilaw na magdadala sa iyo sa lugar kung nasaan ang mga ninuno,” describes Datu Baguio.)

No particular age is required for the inception of the process, but from my observation, corroborated by general testimony, I believe it is performed usually from the age of puberty onwards.

The operator is nearly always a woman, or a man who might identify as a woman,17 who has acquired a certain amount of skill in embroidering. These professionals are not numerous, due, possibly, to the natural aversion felt by women for the sight of blood, as also to the fact that no remuneration is made for their services, though this last reason alone would not explain the paucity. (note: Among the modern Matigsalug-Manobo, cis men also perform tattooing)

17One meets occasionally among the peoples of eastern Mindanáo certain individuals who are known by a special name and who are reputed to be incapable of sexual intercourse. The individuals whom I saw were most feminine in their ways, preferring to keep the company of women and to indulge in womanly work rather than to associate with men.

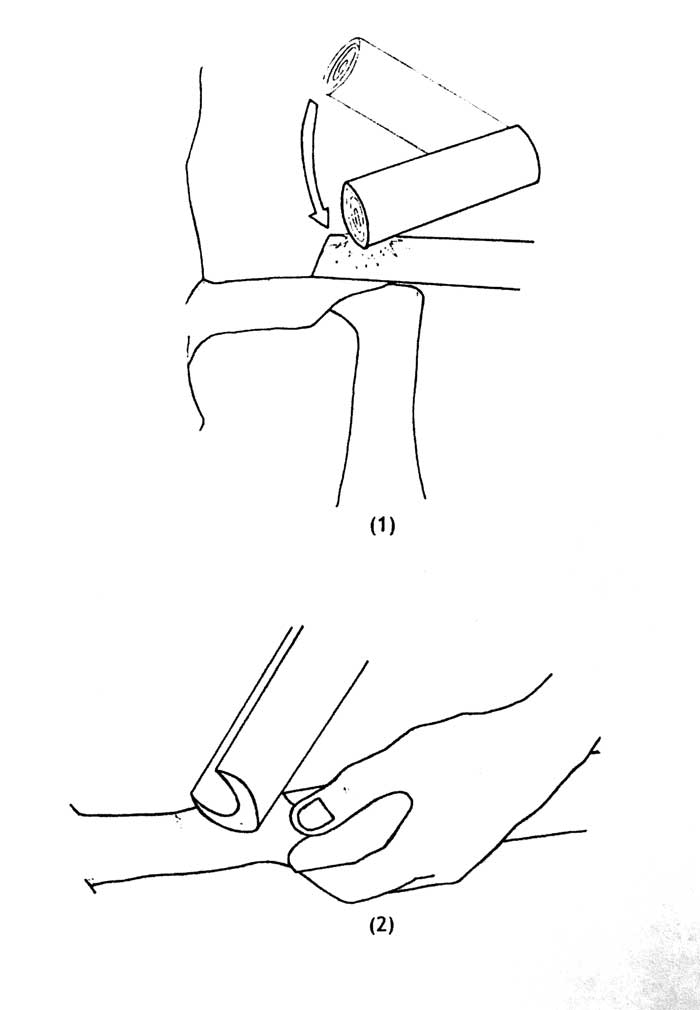

The process is very simple. A pigment is prepared by holding a plate or an olla, over a burning torch18 made of resin until enough soot has collected. Then without any previous drawing, the operator punctures, to a depth of approximately 2 millimeters, the part of the body that is to be tattooed. The blood that flows from these punctures is wiped off, usually with a bunch of leaves, and a portion of the soot from the resin is rubbed vigorously into the wounds with the hand of the operator.

18Saí-yung (Canarium villosum).

The process occupies a variable length of time, depending on the skill of the operator and on the endurance and patience of the subject. It is painful, but no such manifestations of pain are made as in teeth grinding. The portion tattooed is sensitive for about 24 hours, but no other evil consequences, such as festering, etc., follow as far as my observations go.

Without the aid of diagrams or pictures it is difficult to describe in an intelligible and comprehensive manner the numerous designs that are used in tattooing. Each locality may have its own distinct fashion, differing from the fashion prevalent in another region. And as the designs seem to be the result of individual whim and fancy it would be an almost endless task to describe all of them in detail. Suffice it to say in general that they follow in both nomenclature and in general appearance the figures embroidered on jackets, with the important addition of figures of a crocodile, and of stars and leaves, as is indicated by the names.19

19Bin-u-á-ja, (from bu-wá-ja, crocodile), gin-í-bang (from gí-bang, iguana) and bin-úyo (from bú-jo’, the betel leaf).

The figures are neither intricate nor grotesque, but simple and plain, displaying a certain amount of artistic merit for so primitive and so remote a people. On close inspection they show up in good clear lines, but at a distance they appear as nothing but dim blue spots or blotches. For durability they can not be surpassed. No means are known whereby to eradicate them. I compared tattoo marks on old men with those on young men and I could not discern any difference in the brightness nor in the preservation of the design.

In men the portions of the body tattooed are the whole chest, the upper arms, the forearms, and the fingers. Women on the other hand, in addition to tattooings on those parts, receive an elaborate design on the calves, and sometimes on the whole leg.

CIRCUMCISION20

20Tú-li’.

Unlike the four modifications already described, circumcision is not for ornamental purposes. According to the Manóbo’s way of thinking it serves a more utilitarian purpose, for it is supposed to be essential to the procreation of children. How such a belief first originated I have been unable to learn, but nevertheless the belief is universal, strong, and abiding. To be called uncircumcised is one of the greatest reproaches that can be thrown at a Manóbo, and it is said that he would stand no chance for marriage unless the operation had been performed; the womenfolk would laugh and jeer at him. So it may be said that the custom is obligatory.

The operation is performed a year or two before puberty. No ceremonies or feasts are held in connection with it. The father, or a male relative of the child, takes the small knife (ba-dí) and placing it lengthwise over the lower part of the prepuce, makes a slit by hitting the back of the knife with a piece of wood or any convenient object at hand. It thus appears that it is not circumcision in the full meaning of the word but rather an incision. This operation is confined to males and is the only sexual modification practiced.

SOURCE: The Manóbos of Mindanáo, John M. Garvan, Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, Volume XXIII, First Memoir (1931)

Pang-o-tub: The tattooing tradition of the Manobo, Published August 28, 2012, Photos by Karla Rimban and Billy Chavez/Alyx Ayn Arumpac/CM, GMA News

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.