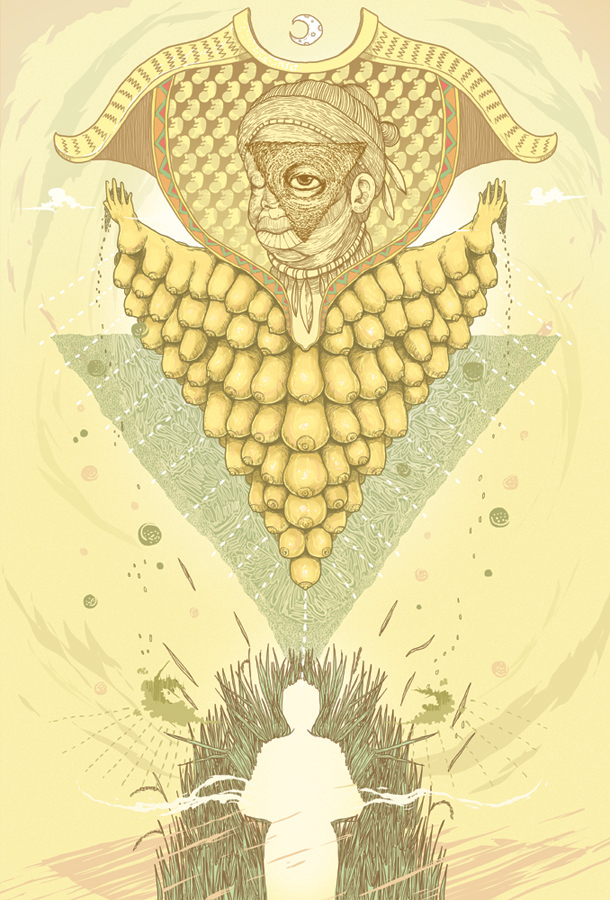

There is a special place in the Bagobo underworld for children who died at their mothers’ breasts. They are nourished by the goddess Mebuyan whose entire body is delicious with milk glands. When they no longer need nursing and can shift for themselves, they go trooping to another district underground to join people who died later in life of disease or any form of sickness.

Lumabat and Mebu’yan

The “Ulit:” Adventures of Mythical Bagobo at the Dawn of Tradition

Long ago Lumabat [1] and his sister (tube’ [2]) had a quarrel because Lumabat had said, “You shall go with me up into heaven.” And his sister had replied, “No, I don’t like to do that.”

Then they began to fight each other. Soon the woman sat down on the big rice mortar, [3]and said to Lumabat, “Now I am going down below the earth, down to Gimokudan. [4] Down there I shall begin to shake the lemon-tree. Whenever I shake it, somebody up on the earth will die. If the fruit shaken down be ripe, then an old person will die on the earth; but if the fruit fall green, the one to die will be young.”

Then she took a bowl filled with pounded rice, and poured the rice into the mortar for a sign that the people should die and go down to Gimokudan. Presently the mortar began to turn round and round while the woman was sitting upon it. All the while, as the mortar was revolving, it was slowly sinking into the earth. But just as it began to settle in the ground, the woman dropped handfuls of the pounded rice upon the earth, with the words: “See! I let fall this rice. This makes many people die, dropping down just like grains of rice. Thus hundreds of people go down; but none go up into heaven.”

Straightway the mortar kept on turning round, and kept on going lower down, until it disappeared in the earth, with Lumabat’s sister still sitting on it. After this, she came to be known as Mebu’yan. Before she went down below the earth, she was known only as Tube’ ka Lumabat (“sister of Lumabat”).

Mebu’yan is now chief of a town called Banua Mebu’yan (“Mebu’yan’s town”), where she takes care of all dead babies, and gives them milk from her breasts. Mebu’yan is ugly to look at, for her whole body is covered with nipples. All nursing children who still want the milk, go directly, when they die, to Banua Mebu’yan, instead of to Gimokudan, and remain there with Mebu’yan until they stop taking milk from her breast. Then they go to their own families in Gimokudan, where they can get rice, and “live” very well.

All the spirits stop at Mebu’yan’s town, on their way to Gimokudan. There the spirits wash all their joints in the black river that runs through Banua Mebu’yan, and they wash the tops of their heads too. This bathing (pamalugu [5]) is for the purpose of making the spirits feel at home, so that they will not run away and go back to their own bodies. If the spirit could return to its body, the body would get up and be alive again.

[1] The first of mortals to reach heaven, and become a god (cf. the “Story of Lumabat and Wari”). In the tales that I have thus far collected, Lumabat does not figure as a culture-hero.

[2] The word indicating the relationship between brother and sister, each of whom is tube’ to the other, whether elder or younger.

[3] The mortar in which rice is pounded is a large, deep wooden bowl that stands in the house. With its standard, it is three feet or more in height.

[4] The place below the earth where the dead go (gimokud, “spirit;” -an, plural ending); that is, [the place of] many spirits.

[5] The same word is used of the ceremonial washing at the festival of G’inum. Ordinary bathing is padigus.

notes* A Bagobo mother does not wean her child, but suckles it as long as it wants to come to her, even when it grows old enough to run about. There comes a day when the child, intent on play, forgets to run to the mother’s breast for food. In such case, she does not call her child, but by and by gives it a little rice, and thus the change is gently accomplished.

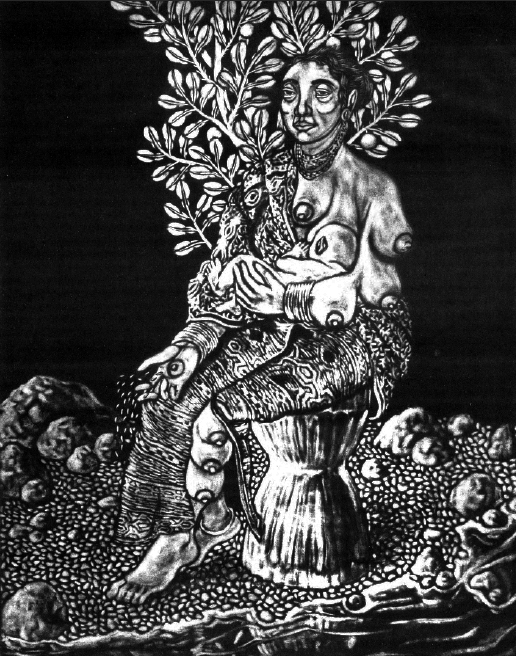

Mebuyan’s position in the spirit world suggests the worship of the “Great Mothers” in northern India. From these generally benevolent village godlings we pass on to a very obscure form of local worship, that of the Great Mothers. It prevails both in Aryan and Semetic lands, and there can be very little doubt that it is founded on some of the very earliest beliefs of the human race. No great religion is without its deified woman, the Virgin, Mâyâ, Râdhâ, Fâtimah, and it has been suggested that the cultus has come down from a time before the present organization of the family came into existence, and when descent through the mother was the only recognized form.

SOURCES: THE SOUL BOOK, Demetrio, Coredero-Fernando, Zialcita, GCF Books 1990

Lubbock, “Origin of Civilization,” 146; Starke, “Primitive Family,” 17 sqq.; Letourneau, “Sociology,” 384

A STUDY OF BAGOBO CEREMONIAL, MAGIC AND MYTH Laura Watson Benedict, New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. XXV, pp. 1—308. Published 15 May, 1916

ALSO READ: Psychopomps (Death Guides) of the Philippines

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.