The story of the Philippine archipelago is a story of movement, which is intertwined with the story of other movements. Movement of people, movement of language, movement of stories, and movement of culture.

The purpose of this analysis is to explain not only the presence of multi-headed beings in Philippine mythologies and epics, but also the regional variations.

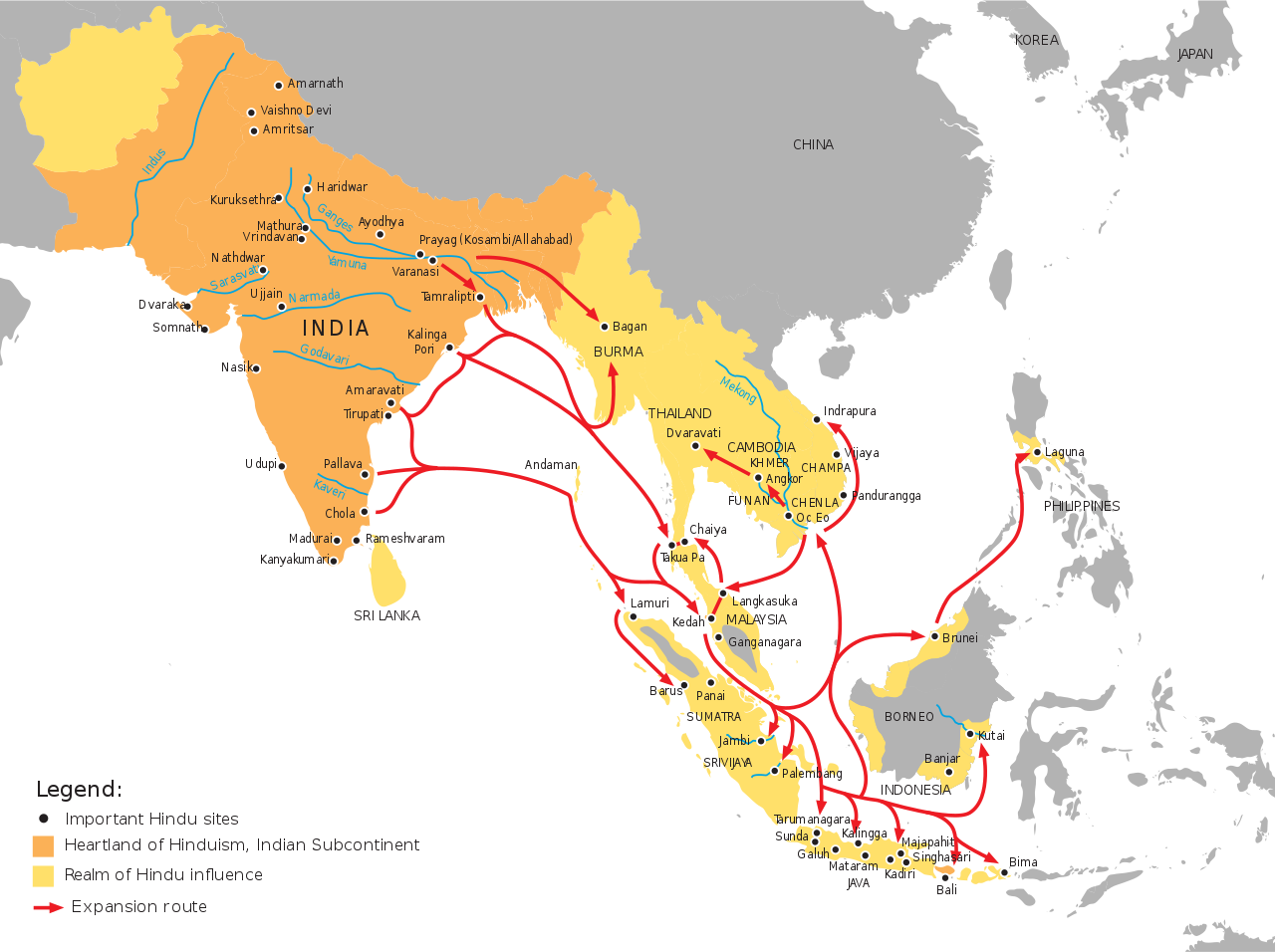

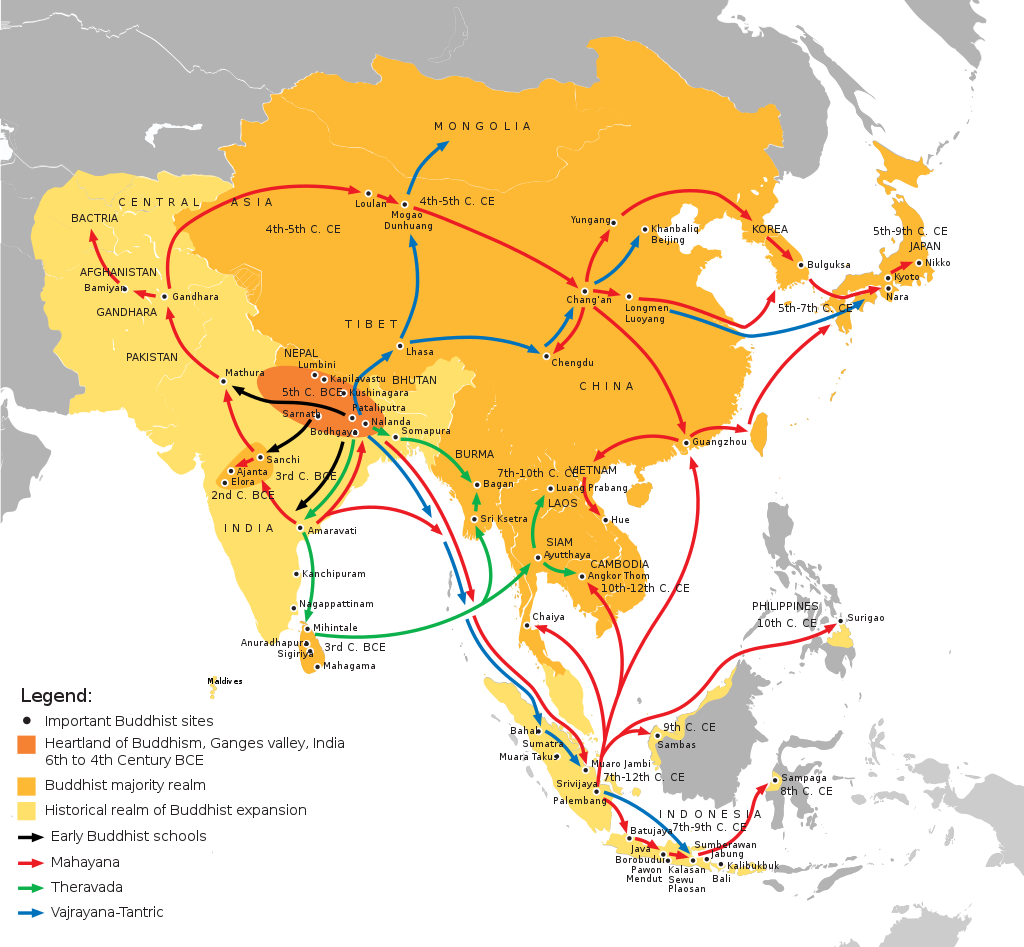

This is an article I’ve been putting off for a long time, and which took much longer to complete than I had anticipated. I enjoy devoting my time to learning more about the archipelago’s complex past, but the further back I need to go, the more I risk losing the attention of readers. It takes time and effort to comprehend trade routes, migration, culture, language, and the spread of Hinduism, then Mahāyāna Buddhism. As many folklorists have previously stated, the lack of existing documentation from the pre-colonial Philippine area necessitates comparative research with neighbouring nations to aid in the development of a deeper knowledge of the various cultural beliefs.

A simple explanation for comparative mythology is that if two or more myths are similar in some way, there are three possible explanations. One is that they form part of a common heritage; another is that a myth or mythological motif has spread from one religion, or region, to another (“diffusion”); a third is that parallel, independent development has produced similar results in two or more different places. Following the third line of reasoning, we might assume one of two possible explanations: either that similar ecological conditions produce similar myths or that the human mind contains archetypes that are expressed in similar symbols everywhere. There is also potential for a combination of these last two scenarios. These myths are generally incorporated into was is held sacred among the particular group telling them. It is important to understand that exploring shared motifs in storytelling do not diminish a people’s rich culture, religion, or what they hold sacred.

In the case of the multi-headed beings of Philippine myths and epics, it traces back a long way, and is just too fascinating for me not to present.

The Emergence and Establishment of the Hindu/ Buddhist Connection

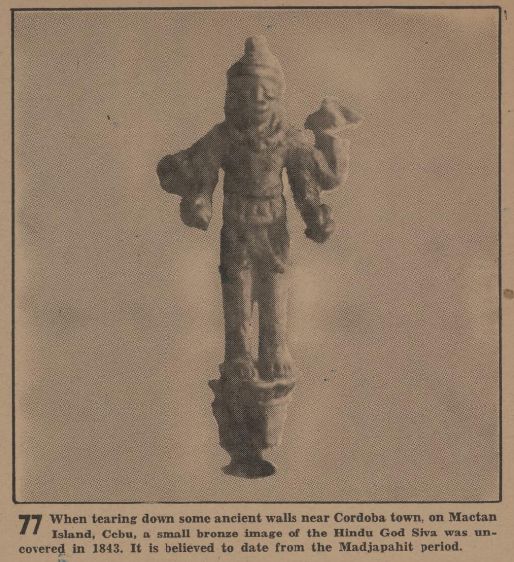

I need to start this article with a lot of preamble for those not familiar with the Hindu and Buddhist influences on the pre-colonial archipelago. As far as I could find, there is no mention in early Spanish accounts of Hindu or Buddhist influences, or reference to religions as being other than Islam and ‘heathenism.’ However, in the late nineteenth century, connections to Sanskrit and Hindu influences were being presented by Filipino writer, politician and labour activist Isabelo de los Reyes, as well as by Filipino physician, historian and politician (of Spanish and Portuguese descent) T. H. Pardo de Tavera who said the following regarding the Sanskrit influence, “The words which Tagálog borrowed, are those which signify intellectual acts, moral conceptions, emotions, superstitions, names of deities, of numerals of high number, of botany, of war and its results and consequences, and finally of titles and dignities, some animals, instruments of industry, and the names of money. I do not believe,and I base my opinion on the same words that I have brought together in this vocabulary, that the Hindus were here simply as merchants, but that they dominated different parts of the archipelago… and that the higher culture of these languages comes precisely from the influence of the Hindu race over the Filipino.”

Henry Otley Beyer found similar connections through the study of folk literature, beliefs, and archeological finds. The 9th century Laguna Copperplate found in 1989 furthered and solidified these theories.

In 1913, Laura Benedict Watson wrote on Bagobo beliefs, “The anthropomorphic and amorphic evil personalities, whose number is legion. The traditional concept of Buso among the Bagobo has essentially the same content as that of Asuang with Visayan peoples. Both Buso and Asuang suggest the Rakshasa of Indian myth.”

In 1930, an often forgotten book by Dhirenda Nath Roy entitled The Philippines and India was published. In it he states ” That Filipino ancestry and lineage imbibed some of the characteristics and customs of the people of India is no longer the subject of speculation”. An entire chapter in the book indicates the evidence of ingrained Hindu culture and civilization in Filipino ancestry.

Filipino folklorists Maximo Ramos, Damiana Eugenio, Francisco Demetrio S.J., Arsenio Manuel and F. Landa Jocano also presented confirmation of the Hindu/ Buddhist connections. American scholar William Henry Scott featured these connections in his magnum opus Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Buddhist influenced gold finds in Butuan, Surigao and elsewhere further established early connections. Mahāyāna Buddhism in SE Asia is rooted in Buddhist traditions that traveled from Northern India through Tibet and China and eventually made their way to Vietnam, Indonesia and other parts of southeast Asia.

Featured in the exhibition ‘Gold of Ancestors: Pre-colonial Treasures of the Philippines’ (Permanent Display)

Image courtesy of Neal Oshima and Ayala Museum

That’s probably the most names I’ve ever used to make a point, but I think you get the idea. The Hindu/ Buddhism influence on the archipelago has become well-established and may have begun as early as the 2nd and 3rd centuries BCE, but certainly through through the 9th -16th centuries BCE.

The Ramayana Epic and the demon King Ravana

The Hindu epic Ramayana may have had the greatest influence on Philippine folk literature. The Story of Rama, about a prince and his long hero’s journey, is one of the world’s great epics. It began in India (est. 400BCE) and spread among many countries throughout Asia. Its text is a major thread in the culture, religion, history, and literature of millions. As the story became embedded into the culture of Southeast Asian countries, each created its own version reflecting the culture’s specific values and beliefs. As a result, there are literally hundreds of versions of the story of Rama throughout Asia, especially Southeast Asia.

Cambodia – Reamker

Java, Indonesia – Ramayana Jawa

Malaysia – Hikayat Seri Rama

Myanmar (Burma) – Yama Zatdaw (Yamayana)

Thailand – Ramakien

Mindanao, Philippines – Darangen, Singkil

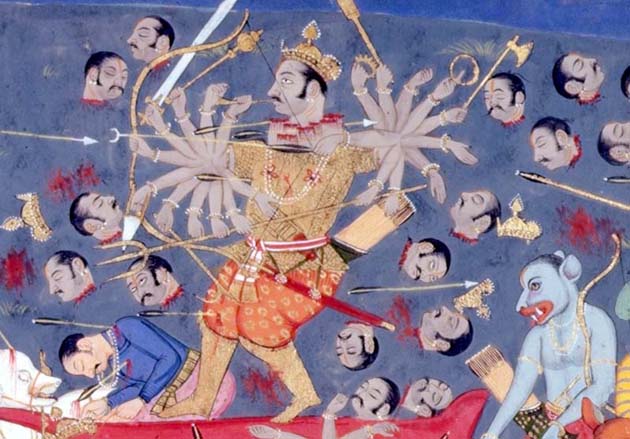

The demon King Ravana, who abducted Rama’s wife Sita and took her to his kingdom, is one of the main adversaries in the epic. In Ramayana, Ravana is the antagonist and comes from lineage that ruled over the Rākṣasa, but he also had many qualities that made him a learned scholar. His minions, the Rākṣasa (male) or Rākṣasī (female) in Hindu mythology are a type of demon. Rākṣasa have the power to change their shape at will and appear as animals, monsters, or in the case of the female demons, as beautiful women. Sound familiar? The Hindu concepts of demons are responsible for evolving animist beliefs regarding the aswang, while the Spanish are responsible for introducing the concept of the devil.

Author / Creator: Sahib Din (Illustrator)

Above is the image of the demon King Ravana, who has ten heads, being decapitated by a shower of golden arrows. In the bottom right corner, is one of Ravana’s demon warriors (Rākṣasa).

This is the final battle between Rama and Ravana. Rama has pursued Ravana in his chariot and fires golden arrows, which turn into serpents as they reach Ravana. The arrows cut off Ravana’s many heads but they immediately grew back again. This goes on for days and nights, and Ravana shoots hundreds of arrows as the two fight to the death.

Matali, Rama’s charioteer watches the struggle and suggests that “To kill Ravana you must use the dreaded arrow of Brahma, given to you by Agastya, which never misses its target”. So Rama shot the divine arrow, which had the power of the gods in it, which pierced Ravana in the heart and killed him.

Multi-Headed Beings in Philippine Myth and Epics

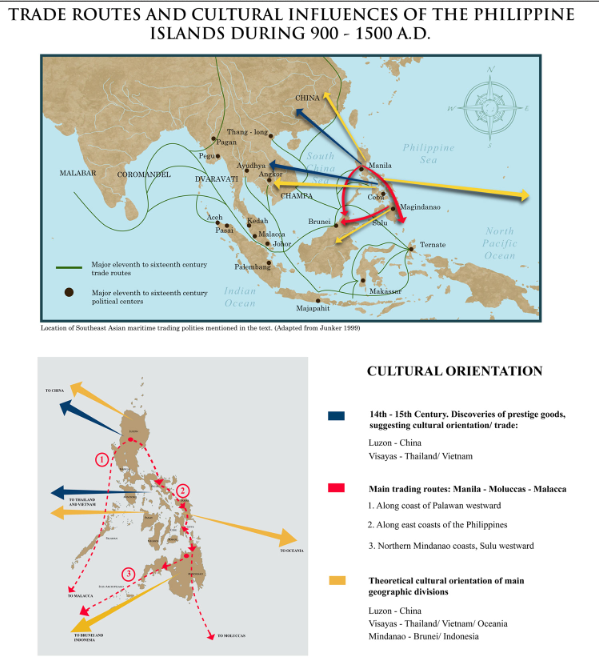

Like the Ramayana, Philippine folk epics are long heroic narratives in verse which recount the adventures of tribal heroes and in the process express the customs, beliefs, and ideals of the people who sing them. Aside from the spread of Hinduism and Buddhism mentioned earlier, the stories were likely also transmitted through migrations within the archipelago and the inter-island trade connections to major and minor trade routes. While the map below is hypothetical, it does tend to explain the differences in cultural influence within major island groups around the archipelago. It also helps hypothesize the similarities and differences between multi-headed beings.

NOTE: I will be providing a brief synopsis of the Philippine myth or epic, with a link to read the full stories.

MINDANAO Multi-headed Characters

1. Maharadia Lawana (Maranao): Our protagonists, Radia Mangandiri and Radia Mangawarna, complete many tasks for the betterment of the kingdom in the Maranao epic, Maharadia Lawana, which is based on the Ramayana. Radia Mangandiri’s wife, Potre Malaila Ganding, is stolen by Maharadia Lawana of the seven heads (although an original text states he was of eight heads, which became seven with no explanation). Like Rama, they must embark on a journey to rescue Potre Malaila Ganding. (click here to read the story)

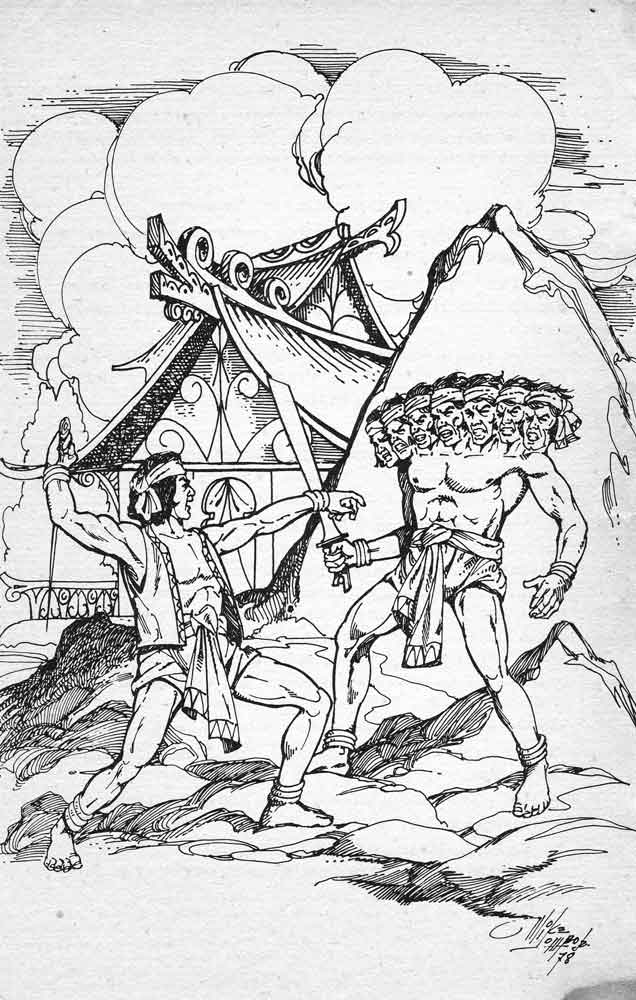

Illustration by Mike Lombo Jr. (Tales from our Malay Past)

2. The Origin of the World (Maranao): In this myth, the soul of every person is found in tightly-covered jars kept in one section of heaven. This particular section of heaven is closely guarded by a monster with a thousand eyes named Walo. Walo in addition to his thousand eyes, has also eight hairy heads. The Darangan epic (considered one of the Ramayana epics of S.E Asia) speaks of Bantugan’s brother Mabaning, husband of Lawanen, entering this section and retrieving the soul of Bantugan.

3. Excerpt from The Creation of the Universe (Bukidnon, Mindanao)

In the beginning, there was no heaven or earth. But there was a banting, a circular space of absolute brightness, surrounded by a rainbow. In it lived three beings; their place of abode was called Bulbulusan Balugtu. One of them had ten heads and one body. He went by the names:

Dadanhayan ha Sugay – The Lord, from whom permission was asked

Takinan Manawbanaw – Chief who owns the drooling saliva

Gumagang-aw – Ten headed

(click here to read the myth)

The ten headed being was considered the “bad” one out of the three, but was eventually responsible for creating the guardian spirits of the earth. I wonder if there is more to this creation myth where the ten heads have more significance.

As per Hindu mythology, the ten heads of Ravana (the antagonist in the Ramayana epic) represent his 10 qualities which are Kama (lust), Krodha (anger), Moha (delusion), Lobha (greed), Mada (pride), Maatsyasya (envy), Manas (mind), Buddhi (intellect), Chitta (will) and Ahamkara ( the ego).

4. Indarapatra and Sulayman (Magindanao): In this epic there are four beasts that have been wreaking havoc on the land. They have caused famine, disease, and forced the people to leave their homes. The fourth of these was also a dreadful bird with seven heads. It lived on Mount Guraya. Our heroes Indarapatra and Sulayman, like Rama and his brother and constant companion Lakshmana, task themselves with freeing the land. (click here to read the story)

LUZON

Gawigawen (Tinguian): There are two tales from the Tinguian ethnic group of Abra. In the first story, Aponitolau visits with the six headed giant, Gawīgawen, in order to get oranges for his pregnant wife Aponibolinayen. In spite of all the warnings during the early part of his journey, Aponitolau continued. Upon coming to the ocean he used magical power, so that when he stepped on his head-ax it sailed away, carrying him far across the sea to the other side. Gawīgawen will give Aponitolau the oranges if he is able to eat an entire caribou. Unbeknown to Gawigawen, Aponitolau enlists the help of insects to complete the task. He is given the oranges and able to get them to his wife, but could not return to her. Instead, other forces held him in the spirit house of Gawīgawen. When Aponitolau’s son, Kanag, is grown and strong, he sets off on his own journey to retrieve his father. He eventually decapitates all the heads of Gawīgawen. (click to read this story)

Gīambólan (Tinguian): In another Tinguian tale the giant has ten heads and is called Gīambólan. Aponītolau dons his best garments, takes his headaxe and spear, and goes to fight. When he reaches the spring which belongs to the ten-headed giant Gīambólan, he kills all the girls, who are there getting water, and takes their heads. The giant in vain tries to injure him. The spear and headaxe of Aponītolau kill the giant and all the people of his town and cut off their heads. Heads are sent in order to hero’s town—giants’ heads first, then men’s, and finally women’s. On return journey Aponītolau is followed by enemies. He commands his flint and steel to become a high bank which prevents his foes from following. Upon his arrival home a great celebration is held; people dance, and skulls are placed around the town. (click to read this story)

NOTE: I’m going refer back to the map of cultural influence and trade routes here. While the map is hypothetical, it’s interesting to note that the multi-headed giant in the Philippine myths and epics noted above have mostly human heads. The trade route appears to travel through Northern Mindanao, along the eastern area of the archipelago and finally through parts of Luzon. There is less Sanskrit/ Hindu/ Buddhist influences in the Cordillera region, so the Tinguian tales mentioned above are important. They seem to be clearly influenced by other epics stemming from the Ramayana, but also include very regional aspects. Fay Cooper Cole writes,“These last two groups (Tinguian and Ilocano) evidently left their ancient home as a unit, at a time prior to the Hindu domination of Java and Sumatra, but probably not until the influence of that civilization had begun to make itself felt. Traces of Indian culture are still to be found in the language, folklore, religion, and economic life of this people, while the native script which the Spanish found in use among the Ilocano seems, without doubt, to owe its origin to that source.”

Again, the exact historical movement of the people is unknown, but the influences can still be seen.

When we look at the Western Visayas, the multi-headed beings tend to change appearance.

WESTERN VISAYAN Multi-headed Characters

1. Negros Occidental: Many legends are told about the origin of the Isles of Seven Sins {Islas de los Siete Pecados) which are located some miles from the mouth of the Bataiano River. These seven islets are grouped together along the Strait of Guimaras. They are of various sizes and are visible from any inter-island vessel plying between Iloilo and Banago or Pulupandan, Negros Occidental. One of the legends is about a monster who had seven heads which were cut off by a hero who wanted to free a beautiful lady from the monster. The heads, each representing a cardinal sin, became the islets.

2. Negros Occidental: Long long ago there lived on the summit of Mount Kanlaon a dragon with a body a mile long and a block thick from which extended seven frightful heads gleaming with green eyes. The people of Negros were in mortal terror of this dragon, that breathed smoke by day and belched fire by night. They found that the only way of appeasing him was to sacrifice a virgin to him every New Year, a sacrifice that became a rite of their religion. It was a young hero who who could speak to animals and “seemed to be a youth from India” that eventually slayed the dragon and freed the land. (click here to read the story)

3. Hinilawod (Sulod, Panay): In the main text of the“Hinilawod” epic of Central Panay, Humadapnon is one of the 3 demigod heroes. He is the offspring of Datu Paubari and Alunsina, the goddess of the South Heavens. Coming from the gods, Humadapnon and his siblings, Labaw Donggon and Dumalapdap posses special powers and all receive assistance from the gods in time of trouble.

Humdapnon was visited by his spirit friends Taghoy and Duwindi in his dream and told him of lovely maiden who lived in a village by the mouth of the Halawod River. The demigod left his dominion to look for the maiden named Nagmalitong Yawa. He brought with him a boatful of crew.

Humadapnon and his men safely traversed a blood-coloured sea with the help of his spirit friends. They landed on an island that was inhabited by beautiful women and headed by the sorceress, Ginmayunan. For seven years, Humadapnon and his crew were imprisoned in the island until Nagmalitong Yawa helped them escape by transforming into a man. Humadapnon and Nagmalitong Yawa were married soon after in Halawod.

During the wedding feast, Humadapnon’s brother, Dumalapdap fell in love with Huyung Adlaw and asked his brother to help him talk to the parents of the maiden. Humadapnon left his new wife and accompanied his brother to the Upperworld where Huyung Adlaw lived.

It took the brothers seven years to come back from their journey to the Upperworld. They arrived just in time for the ceremony that will have Nagmalitong Yawa married to Buyung Sumagulung, an island fortress ruler, in a ceremony. The brothers were enraged and killed all the guests and the groom. Humadapnon also stabbed his wife because the treachery only to feel remorse later on. He asked his spirit friends and found out that his wife only agreed to marry Buyung Sumagulung because her mother, Matan-ayon, convinced her that Humadapnon is not coming back.

Upon learning of this, Humadapnon asked his sister, Labing Anyag, to use her powers to bring Nagmalitong Yawa back to life. Seeing how remorseful he is, Labing Anyag agreed. However, Nagmalitong Yawa was so ashamed of agreeing to marry Buyung Sumagulung that she ran away to the underworld and sought the protection of her uncle Panlinugun, who is lord of the earthquake.

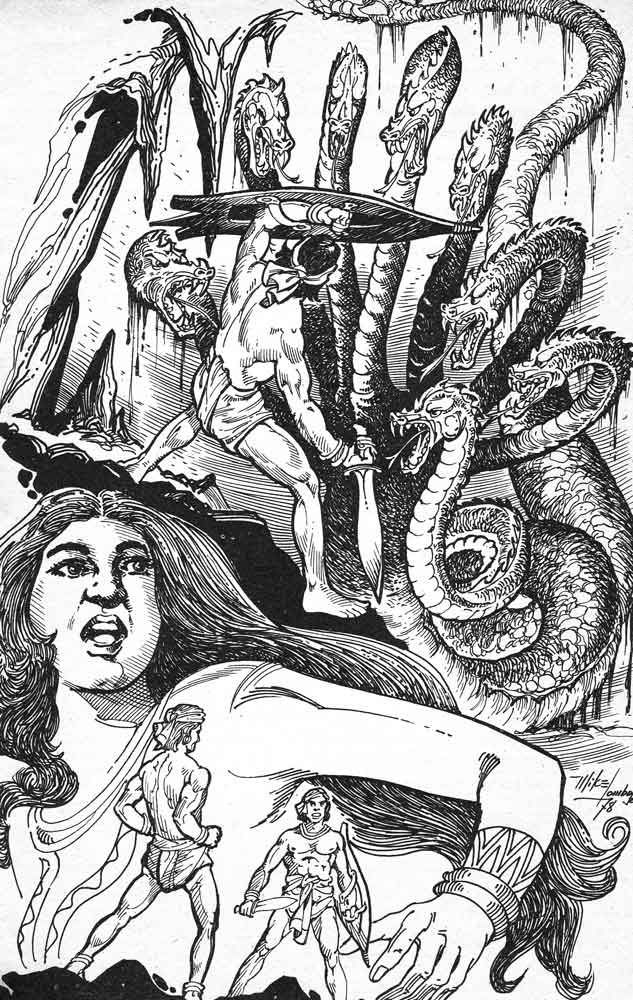

Humadapnon had to kill an eight-headed serpent named Sikay Pedalogdog in his pursuit of Nagmalitong Yawa. Then he had to duel with a young man who spirited his wife away. The duel ended when Alunsina intervened and revealed that the young man is also her son, Amarotha. This son died during childbirth and was brought back from the dead to keep Alunsina company. Alunsina decided that both Humadapnon and Amarotha deserved a piece of Nagmalitong Yawa so she cut the girl in half and gave a piece each to her sons. Each half turned into a whole live person. Humadapnon brought his wife back to Panay. (click here to read a full synopsis of this segment)

Illustration by Mike Lombo Jr. (Tales from our Malay Past)

In variant excerpts of the Hinilawod recorded by Jocano, Labaw Donggon and his two brothers, sons of Datu Paubari and goddess Alunsina of Halawod encounter two multi-headed beings. After travelling night and day in their magic sailboats, the brothers reached a region of Eternal Darkness where they fought and vanquished a three-headed monster named Tabuknun.” Later in the tale, they travelled for several moons until they reached a place called Tarambuan-ka-banwa where they met Balanakon, a two headed monster which guarded the Kalbangan (narrow ridge) leading to the place where Lubay-Lubyok Hanginun lived. (click to read this story)

Image from OUTLINE OF PHILIPPINE MYTHOLOGY by F. Landa Jocano (1969)

Artist uncredited

NOTES: You’ll notice that the multi-headed beings in the Visayas have become a snake,”dragon” or a serpent, and is not always the main antagonist. The “Hinilawod” or Sugidanon is very unique to Panay and reflects the history, values, and environment of the island, but are also very reminiscent of other epics, including the Ramayana. The differences may be attributed to additional exposure to the Mahabharata epic and/or other Buddhist scripture. I’m also reminded of Bakunawa’s progression, which was influenced by the Hindu deities Kala/ Rahu. The enormous Minokawa bird from Mindanao beliefs, the serpents of the Visayas, Bicol, and the Laho of Luzon were all impacted by the same myth. Although the precise movement of people or trade is unknown, we do know that there are cultural linkages between Mindanao and Panay, as evidenced by the Binanog dance. The Binanog dance of the Panay-Bukidnon ethnic community is inspired by the “banog,” a term for hawk. The dance imitates the movement of a hawk. On Mindanao these are known as the Amaemaetatok/ Binanog Agusan Manobo Bird Dances.

If you’ve ever studied Roman or Greek mythology (stick with me), you might be thinking that some of this sounds eerily similar to Hercules’ second labour to slay the Lernean Hydra, the serpent with nine heads. One of the Hydra’s nine heads was immortal and thus indestructible, making it a difficult target. Hercules’ penance for murdering his wife Megara and their children included this labour.

Something else you may notice is that Humadapnon in the Sugidanon, has a similar experience to Odysseus, after the latter returned home from the Trojan War. As a result of the prolonged absence, his wife remarried under the mistaken belief that he had died. This passage does not appear in the Ramayana.

You can stop your heart palpitations and put the keyboard down, I’m not going to tell you that the Sugidanon is based on Homer’s Odyssey or Hercules. Instead, I am firm in my belief that there are shared themes and stories from the Earth’s early peoples that have been told for so long that there are innate universal themes, motifs, and characters in epic folk literature, regardless of who was the first to write them down. In narratology and comparative mythology, the hero’s journey, or the monomyth, is the common template of stories that involve a hero. You may see the connection to Hercules and Odysseus because that was what you were taught in school or what was accessible. I personally see much more commonality with Chinese, Japanese, and other SE Asian folk beliefs and mythologies.

Throughout Asia, mythologized snakes and snakelike beings have various roles, including the calendar system, poetry, and literature. The functions of the multi-headed serpents in the Visayas seems to fit with some functions of the naga in Hindu and Buddhist scripture. Hindu scriptures mention nagas, who are a class of demigods or semi divine beings who live in the subterranean world, known as Patala. They protect the treasures hidden in the earth and have the ability to assume human form. By nature they are good, but they can become destructive and vengeful if disrespected or not treated well. In Buddhism, nagas are often represented as door guardians.

Comparative Multi-Headed Serpent Beings in Epics/ Mythology

1. Let’s address the Hydra in the room. The oldest surviving multi-headed serpent narrative appears in Hesiod’s Theogony, while the oldest images of the monster are found on a pair of bronze fibulae dating to c. 700 BC. In both these sources, the main motifs of the Hydra myth are already present: a multi-headed serpent that is slain by Heracles and Iolaus. The Hydra had many parallels in ancient religions. In particular, Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian mythology celebrated the deeds of the war and hunting god Ninurta, whom the Angim credited with slaying 11 monsters on an expedition to the mountains, including a seven-headed serpent. More on this later.

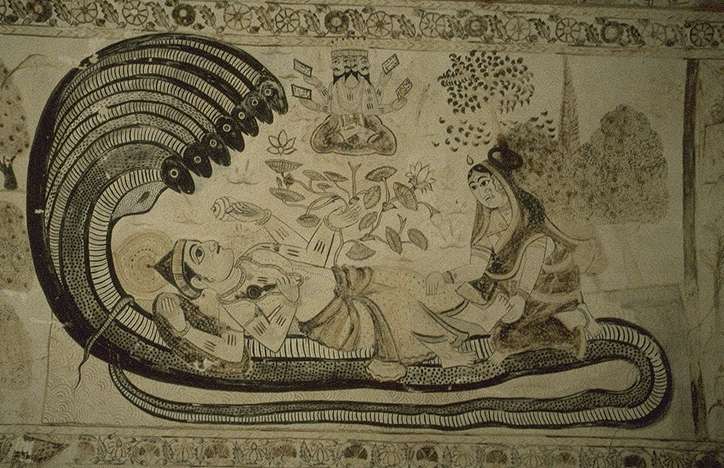

2. As per another great Indian epic, the Mahabharata, the five headed serpent Shesha was born to sage Kashyap and his wife Kadru. Kadru gave birth to a thousand snakes, of which Shesha was the eldest.. This large snake is the Nagaraja or the King of the Naga (snake) race and one of the primal beings of creation itself. Adishesha holds an important position in Hindu mythology, philosophy, art, culture and literature. In Buddhism, he is considered to be Vasuki.

In the Puranas, Shesha or Sheshanaga is believed to hold all the planets of the Universe on his vast hoods. An ardent devotee of Lord Vishnu, he constantly sings the glories of his Lord from all his mouths. He is sometimes referred to as Ananta Shesha, which means the Endless or the Infinite One. It is said that when Adishesha uncoils, time begins to move forward and creation starts to take place. When he comes back to his coiled position, time stands still and the Universe ceases to exist. When he shifts the Earth, this is the cause of earthquakes.

Shesha images are present throughout Southeast Asia.

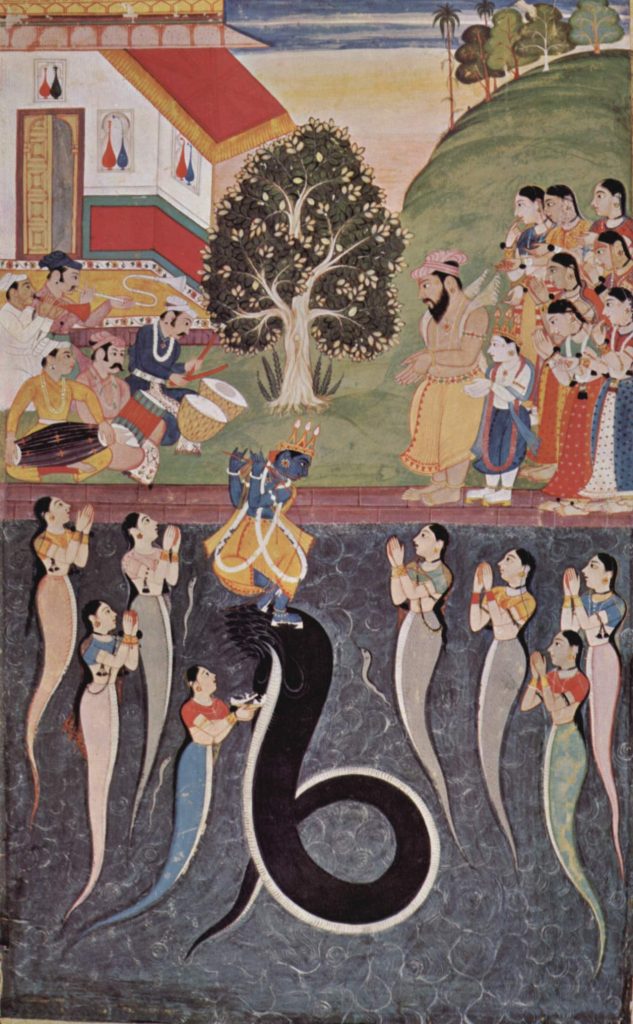

3. In Buddhist stories, Kāliya was a five-headed sea serpent king, who poisoned water and land, until the god Krishna defeated him in battle. After Krishna spared his life, Kaliya then began to worship Krishna. The story of Krishna and Kāliya is told in the sixteenth chapter of the Tenth Canto of the Bhagavata Purana.The date of composition is probably between the eighth and the tenth century CE, but may be as early as the 6th century CE.

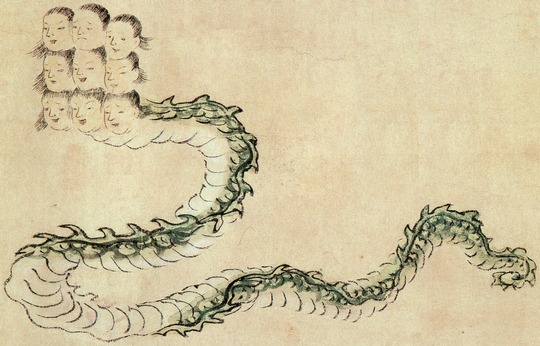

4. Xiangliu is a venomous nine-headed snake monster that brings floods and destruction in Chinese mythology. Xiangliu may be depicted with his body coiled on itself. The nine heads are arranged differently in different representations. Modern depictions resemble the hydra with each head on a separate neck.Older wood-cuts show the heads clustered on a single neck, either side-by-side or in a stack three high, facing three directions.

According to the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhaijing, third century BCE to second century CE), Xiangliu (Xiangyao) was a minister of the snake-like water deity Gonggong. Xiangliu devastated the ecology everywhere he went. He was so gluttonous that all nine heads would feed at the same meal. Everywhere he rested or breathed upon (or that his tongue touched, depending on the telling) became boggy with poisonously bitter water, devoid of human and animal life. When Gonggong received orders to punish people with floods, Xiangliu was proud to contribute to their troubles.Eventually, Xiangliu was killed, in some versions of the story by Yu the Great, whose other labors included ending the Great Flood of China, in others by Nüwa after he was defeated by Zhurong. The Shanhaijing says his blood stank to the point it was impossible to grow grain in the land it soaked and the area flooded, making it uninhabitable. Eventually Yu had to restrain the waters in a pond, over which the Sky Lords built their pavilions.

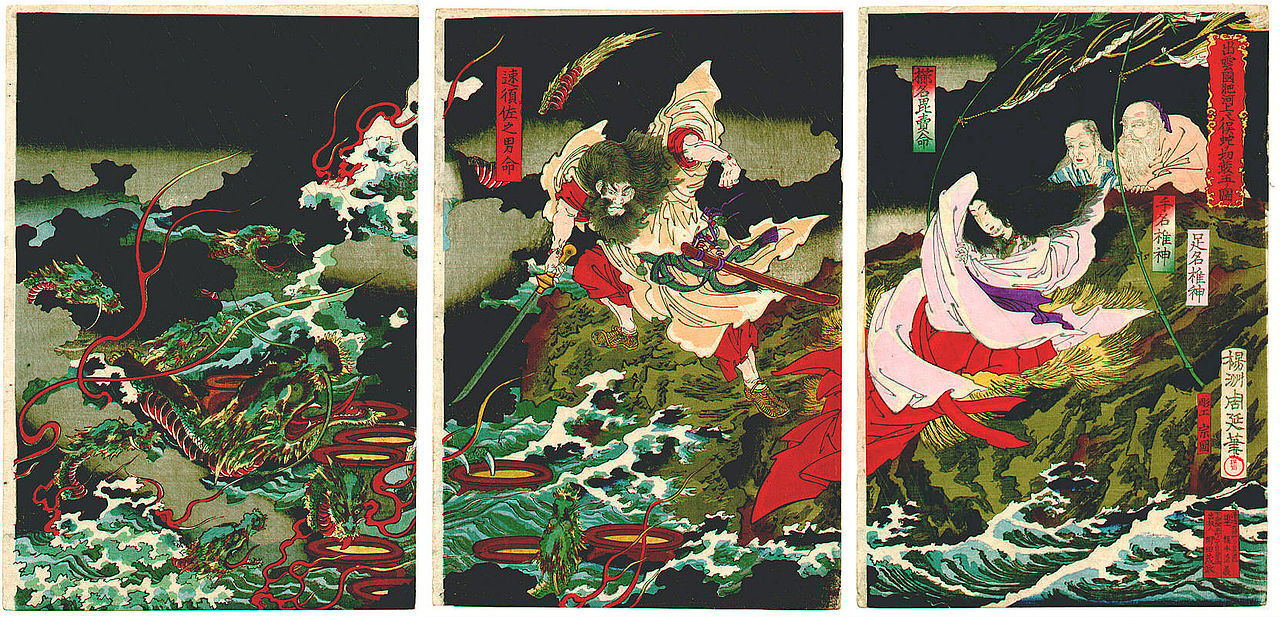

5. Yamata no Orochi is a legendary eight-headed and eight-tailed Japanese dragon/serpent. Yamata no Orochi legends are originally recorded in two ancient texts about Japanese mythology and history. The 680 CE Kojiki transcribes this dragon name as 八岐遠呂智 and the 720 CE Nihon Shoki writes it as 八岐大蛇. In both versions of the Orochi myth, the Shinto storm god Susanoo is expelled from Heaven for tricking his sister Amaterasu, the sun goddess. After expulsion from Heaven, Susanoo encounters two “Earthly Deities” (國神, kunitsukami) near the head of the Hi River (簸川), now called the Hii River (斐伊川), in Izumo Province. They are weeping because they were forced to give the Orochi one of their daughters every year for seven years,* and now they must sacrifice their eighth, Kushi-inada-hime (櫛名田比売, “comb/wondrous rice-field princess”), who Susanoo transforms into a kushi (櫛, “comb”) for safekeeping. Susanoo eventually slays the dragon with a “ten-grasp-saber.”

*NOTE: This feels very reminiscent of the original Bisaya tale of Bakunawa and the Seven Moons. Instead of the children of earthly deities, Bakunawa has been devouring what used to be 7 moons in the sky. In the Bakunawa tale, however, it is the people that must rescue the last moon.

CONCLUSION

The Ramayana became embedded into the culture of Southeast Asian countries and each created its own version reflecting the culture’s specific values and beliefs. These adaptations also reflected environment and incorporated folk religion. We can make direct comparisons to the multi-headed demon King Ravana from the Ramayana in some of the tales throughout the Philippine archipelago. I did try to trace back the origin of Ravana, which led to possible origins in Southwest Asia, but it became too hypothetical for presentation.

There seems to be a separate branch of evolved multi-headed serpent stories present in the Western Visayas. These share motifs with the variations also present in China and Japan, which may stem from the Buddhist story of Kāliya and Krishna.

Loving history as much as I do, I can’t gloss past the cultural links between India and the Greco-Roman world. As soon as the Greeks invaded Northwestern South Asia to form the Indo-Greek kingdom, a fusion of Hellenistic and Buddhist elements started to appear, encouraged by the benevolence of the Greek kings towards Buddhism. This artistic trend then developed for several centuries and seemed to flourish further during the Kushan Empire from the 1st century CE.

The multi-headed dragon/serpent stories presented above tend to share common traits. The stories existing in the Philippines could have been adapted from the Buddhist telling as it was brought along the silk road and sea routes with the spread of Mahāyāna Buddhism, eventually making it to the archipelago. I’m not going to propose, as others have, that the second labour of Hercules vs. the Hydra inspired that of Krishna and Kāliya. It would, however, be weird if I ignored the Hydra and the historical connections between Greece/ Rome – India – East Asia without explanation. Still, the best one can find in connecting these stories is that they share motifs and established trade routes. As far as the Greek Hydra directly influencing Hindu and Buddhist stories, that’s a hypothetical proposition. The Greeks documented it first, but the multi-headed mythical being could have been established throughout the surrounding regions for thousands of years.

Still, the potential for shared culture was considerable. For those unfamiliar with how extensive the silk road trade route was, here is a rough map. (130 BCE- 1453 CE)

Spices from the East Indies, glass beads from Rome (which have been discovered in Southeast Asia), silk, ginger, and lacquerware from China, furs from animals of the Caucasian steppe and slaves from many locations all travelled along the Silk Road.

Some effects were cultural. For example, during the rule of the Tang dynasty (618 to 907 CE) of China, sculptures of camels from the caravans that frequently traded in China were placed in graves.

Where the influence of Hellenism (culture of ancient Greece) on Asia is concerned, I would lean more on the side of the Japanese scholar Okakura Kakuzō (1863 – 1913) who said that by the time Greek influence reached the east it would have been greatly diluted. Although he can not provide proof, he said that influence from Hellenism may potentially be seen in some Japanese art around the 8th century CE. In other words, if Greek influence made it to Eastern Asia, it would have been essentially unrecognizable.

While I love to study the origin, evolution and influences of myth and folklore, I never lose sight that stories are unique to their region and should be cherished as such. These stories represent a pathway to the culture, religion, history, and literature of the archipelago. Philippine epics are magnificent and significant works. The presence of a multi-headed character in the literature of so many ethnic groups illustrates not only a shared literary heritage spanning two millennia, but also the unique diversity of the cultures. The shared motifs illustrate how expansive trade routes were, and assist us in understanding the environments that formed the sacred or unique aspects in the various myths and epics.

I wonder if my opening statement has a different meaning at the end of this article?

The story of the Philippine archipelago is a story of movement, which is intertwined with the story of other movements. Movement of people, movement of language, movement of stories, and movement of culture.

Recommended Reading

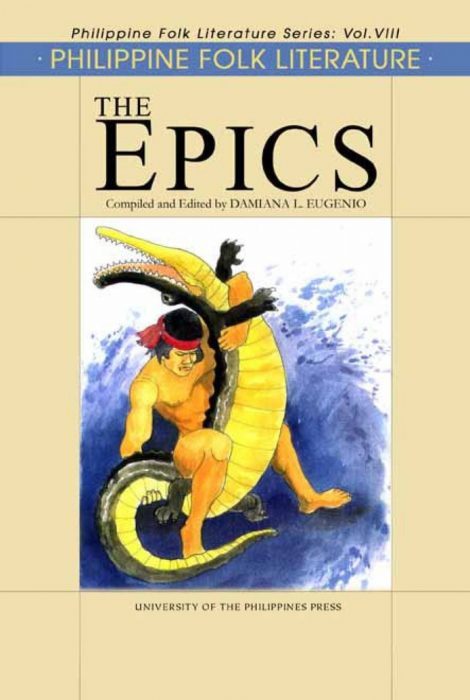

Philippine Folk Literature Series: The Epics, Vol: VIII

by Compiled and Edited by Damiana L. Eugenio

Philippine Folk Literature: The Epics presents twenty-three folk epics collected from some fourteen ethnolinguistic groups in the country. This is the eighth volume being added to the original seven-volume Philippine Folk Literature Series.

This volume thus gives the reader an opportunity to get acquainted with these folk epic heroes and the values and ideals they stand for.

AVAILABLE IN THE US at Arkipelago Books

AVAILABLE IN THE PHILIPPINES through UP Press

SOURCES:

La Religión Antigua de los filipinos, Isabelo de los Reyes ,(1909)

El Sanscrito en la Lengua Tagalog T. H. Pardo de Tavera, (Paris:’ Im- primerie de la Faculte de Medicine, 1887)

Philippine saga : a pictorial history of the Archipelago since time began / H. Otley Beyer, Jaime C. de Veyra, Capitol Publishing House, (1952)

Bagobo Myths, Benedict, Laura Watson, Publisher The Journal of American Folklore (1913)

The Philippines and India, Dhirendra Nath Roy, P.I. [Oriental printing], (1930)

The Ramayanas of Southeast Asia, University of Washington, https://jsis.washington.edu/seac/resources/educators/ramayanas-of-southeast-asia/

Tales from our Malay Past, Mela Ma. Roque, Filipinas Foundation Inc, (1979)

Philippine Folk Literature: The Myths, Damiana Eugenio, UP Press, (2001)

The Soul Book, Demetrio/ Fernando/ Lialcita, GCF Books (1991)

Traditions of the Tinguian: A Study in Philippine Folk-Lore, Fay-Cooper Cole, Assistant Curator of Malayan Ethnology, 1915

Philippine Folk Tales, Mabel Cook Cole, A.C. McClurg & Co. (1916)

Analysis Of Ramayana And Odysseus, https://www.ukessays.com/essays/english-literature/analysis-of-ramayana-and-odysseus-english-literature-essay.php

Mahayana Buddhism, Jonathan A. Silk, Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mahayana

Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion, Najeeb M. Saleeby, Manila Bureau of Public Printing (1905)

Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Ogden, Daniel, Oxford University Press, (2013)

ANTHOLOGY OF WORLD SCRIPTURES, Robert Van Voorst, fifth edition, Thomson Wadsworth, (2007)

Bhagavata Purana, Canto Ten, Chapter 16 The account of Krishna and Kaliya, as told in the Bhagavata Purana.(Full Sanskrit text online, with translation and commentary.)Handbook of Chinese Mythology, Yang Lihui & al., Oxford University Press, (2005)

The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters. Chamberlain, Basil H. Tuttle reprint. 1981 [1919]

Yamata-no-orochi, Encyclopedia of Shinto, http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=176

Mythology of Greece and Japan: Archetypal Similarities, George A. Sioris, Sterling Publishers, (1987)

Alexander the Great: East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan, Tanabe (Katsumi.) , NHK Promotions, (2003)

“Maritime Buddhism”. Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018).Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford University Press

pre-Spanish Philippines, Juana J. Pelmoka, Ph.D. (1996)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.