Most great folk tales in the Philippines include the storyteller mentioning the infamous tree known as the Balete (Ficus Indica), which is consistently associated with both magical and nightmarish entities. With its massive height, haunting appearance composed of large twisting roots that seem to be strangling its own trunk, it certainly casts a foreboding shadow to passersby. The Balete is an easy target for anyone to start their own horror tale.

Regardless of physical appearance, trees are quiet noticeably mentioned throughout our own mythology and lore. Some are associated with engkantos and other nature spirits while others plays a vital role in the shamanistic/animistic culture of our Babaylan. Perhaps more than just a source of physical materials such as wood, paper and even medicine, trees can also provide impalpable treasures that we must learn to conserve and protect.

Deeper than the roots below

We can trace the Balete tree origins to the family of fig plants known as Epiphyte. An epiphyte is a plant that initially grows harmlessly upon another plant (such as a tree) and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, and sometimes from debris accumulating around it. Eventually though, these plants may kill their host tree as they strangle its body with their roots that grow downward until they reach the peak of their maturity. In India and neighboring countries, it is known as Banyan or Banian and considered as a holy tree for Hindus since it is usually connected with deities such as Shiva and Krishna.

In the Philippines, Balete is notoriously labelled as the domicile of engkantos and other fearsome spirits like the Tikbalang and Kapre. Besides the one located on Balete Drive in Manila, there are three known Balete trees that can be found in our country and each of them are situated in different regions of the Philippines. In the province of Aurora in Luzon, there stands a 600 year old Balete tree known as the “Millenium Tree”. In the Visayas, a Balete tree is believed to be the oldest tree in the province of Negros Oriental, and in the Central Visayas, a mystifying 400 year old Balete in Siquijor produces a spring of clean water that some of the people are stiff baffled as to where its coming from.

Hair raising tales surround these trees which why most people don’t cut them down, but instead show respect whenever they pass by. At some point, sacrifices were also offered to these trees to appease the spirit who dwells in it and may induce harm to individuals who pass near. Besides it being the home of spirits, our ancestors also had other views on the Balete.

A shamanic calling is when people are called by the spirits to become shamans. As stated by Francisco Demetrio in his essay “The Engkanto Belief”, this phenomenon in the Philippines could be attributed to the disappearance of the Babaylan after the advent of Christianity. Those chosen would sometimes be found sitting at the top or underneath the Balete tree. This is highly reminiscent of Siddharta Gautama Buddha sitting in the Bodhi Tree, which is the prelude of Buddhism. Interestingly, both the Bodhi tree (Ficus Religiosa) and Balete come from the same species of Ficus or Figs. It was said that the spirits have already possessed the candidate shaman once they are found in this state – which will be the starting point of their life as the medium between humans and spirits.

Francisco Ignacio Alcina’s “History of Bisayan Islands” depicted these Babaylans as if the are under fits of madness. While wearing self-made ornaments and gold jewellery, they stay beside the Balete tree where the spirits that called them will initiate them with the gift of healing and clairvoyance, among others.

I found the calling, initiation and the return of the shaman shares the same pattern of hero myth that is explained by Jospeh Campbell in his book “The Hero With a Thousand Faces”. In this comparison, the Babaylan (Hero) is summoned to a certain journey or quest (the calling) where he will face inhuman challenges which will transform or ascend his inner self (initiation). After this he will be rewarded with boons (the power to heal or to to divine) which he will use for the benefit of the people (return).

A treasure inside the “heart” of a tree

More than the fruit it produces – which is filled with energy giving nutrients – the Banana may have a lot more to offer. According to some, the blossom of the banana contains mystical powers highly sought by valiant men. A “mutya”, as stated in Iloko and Tagalog tales from the records of Dr. Maximo Ramos, is a powerful stone the size of one’s big toe that can only be acquired when an east facing blossom of the Banana tree (Puso ng Saging) opens up at midnight. Should an individual manage to anticipate the fall of the mutya, he should catch the magical stone using his mouth.

The real struggle will commence once the guardian of the mutya ( usually the engkantos that inhabits the Banana tree) will try to seize the one who capture it until sunrise. A successful individual is said to acquire a strength that will never falter or an irresistible charm to women. However, if you let the stone come out of your mouth during the confrontation with the mutya guardian, you will be inflicted with insanity.

In other version of stories, the mutya can be found in the flower of the Kusul Plant (a kind of Ginger in Pampango) during moon rise. If one will embed the stone from the Kusul plant in his body, they will become invulnerable.

In “The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology”, Dr. Ramos also narrates a story coming from Zambales which mentions other plants also possess their own “mutya” which varies in power and abilities depending on the plant where they can be found. However, it is not stated which other plants possess this magic stone.

More than just leaves and branches

Some other notable and interesting plants house different engkantos and other worldly beings, including the Takang Demonio (Sterculia Foetida) – an unusual plant reeking with foul odors where the Tulung and Binangunan (creatures similar to the Tikbalang) from Mt.Pinatubo are said to reside.

The Mangmangkit of Iloko tales resides in forest trees and is the reason woodcutters would utter invocations or permission before they proceed with their logging activity. The chant below from Dr. Ramos’ book, is one of these.

Bari – Bari

Di ka agunget, Pari

Ta Pumukan Kami

Iti pabakirda kami

(Bari-bari

Do not be angry my friend

For we must cut down some

Of what we have been told to.)

The Pugot, another giant engkanto is quite fond of large fruit bearing tress such Santol, Tamarind and Duhat as its own dwelling place.

An old tree found in Quiangan (Kiangan), Ifugao is considered as a “Tree of Life” wherein their own life is interconnected with the life of the tree itself. Another sacred tree called Patpatayan is among the station where the people of Sagada will offer a pig and pieces of meat shared by men who joined the so called “March of Indians” which is a part of the “Begnas di Yabyab”, a ritual made before the people will start planting to ensure that their harvest will be bountiful.

In a tale from the Tinguian, a tree that bears agate beads will talk in strange tongue when a branch is broken, as was discovered by a hunter inside a cave. Thinking that it was a way for his people to gain enormous wealth, they tried to look for the tree once more only to find that it was inhabited by an evil spirit who left strange carvings inside the cave where the tree was once found.

Connecting both spirits and man

Trees are evidently one of the most universal symbols or motifs in ancient religions and mythologies. From the “Tree of Life” accounts in Judaism down to the sacred Oak worshipped by Druids and other Pagan practitioners, man seems to have had a strong connection in the mystical aspect of trees – knowing that the lives of ancient people highly revolves around the forest which provides all their necessities. Moreover, due to the fact that trees reflect the same image of the life cycle (birth/germination, death/withering) its no wonder that man was so fascinated by them.

The Philippines and its neighboring countries from the south east share a common belief that trees house different kinds of spirits and entities that can be either malignant or benign. The Balete, or Banyan Tree in particular, is a central figure in Indian religion – which they consider as one of the holy trees where gods and spirits reside. Similarly in Thailand, good luck spirits called Nang Ta-Khian inhabit the Ta-Khian tree (Hopea Adorata) which is endemic to Thailand, Cambodia and Laos.

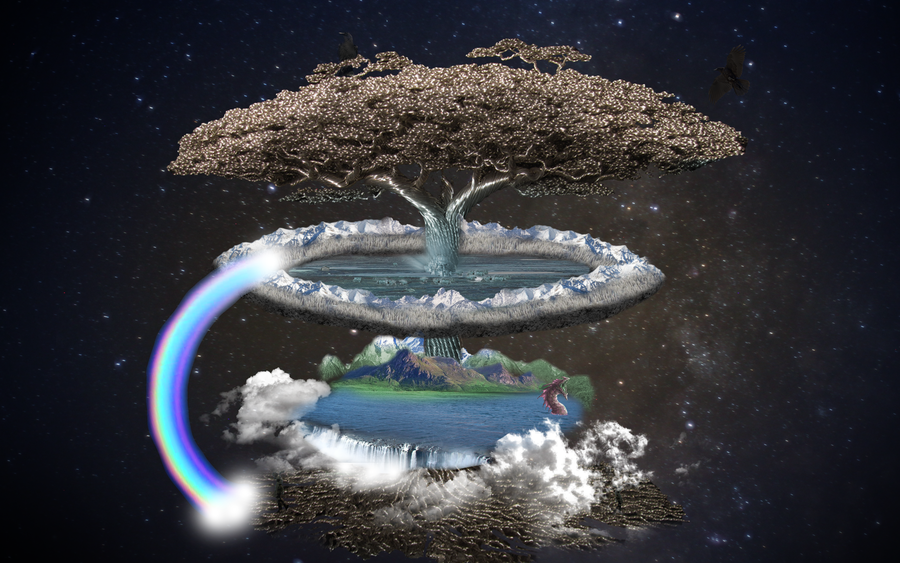

In addition to this, trees are considered to be the gateway that connects the three worlds (world of men, the upper or sky world and the under world) and allows each of the inhabitants of these world to interact with one another; making trees one of the oldest symbols of the Axis Mundi or the interconnection between heaven, hell and our world. This could explain why Babaylans have a strong attachment with trees like the Balete as they partake in the role of a mediator between the three worlds.

Reconnecting Our Roots

Many of the important beliefs and tales of the ancient past have been slowly fading in our memories, just as how trees are diminishing in our surrounding as the majority of people focus on the promises of industrial and technological advancement. It seems that we willingly disconnect ourselves in the natural world, abandoning it in exchange for artificial and material inclined progress that slowly kills not just our environment but ourselves as well. Once it was believed that the life of trees are intertwined with man’s mortality as if they share the same string of fate; when the trees have all died, man will perish too. Science has now proven this to be true.

Trees consist of a sacredness that was once known and intertwined with all the rivers, forests and even the animals – which are all part of our life both in the spiritual and material realm. We must relearn to give respect and care to them before the time comes that we find ourselves withering together with them. This is the right moment for us to reconnect our roots in order to relive the days that people, the trees, and nature itself are allies instead of enemies.

ALSO READ: ENGKANTO & ANITOS: Could Science Be Close To Proving They’re Real?

Currently collecting books (fiction and non-fiction) involving Philippine mythology and folklore. His favorite lower mythological creature is the Bakunawa because he too is curious what the moon or sun taste like.