by F. Landa Jocano

The value of myths and legends to students of Filipino society and culture cannot be overemphasized. These narratives are basic to our social tradition; they constitute part of our social heritage. Yet the study of Filipino mythology has not apparently attracted the attention of many educators and students. Only few, so far, have shown interest in it. Undoubtedly, this aspect of our literature is the most neglected field of study. Many colleges and universities do not carry a course on it in their curriculum; instead, they have Greek and Roman mythologies as major offerings. While it is true that liberal education must be internationally oriented, it must not be so detached from the local culture as to lose its meaning and perspective. A balance has to be maintained or students become dislocated in the end. After all they are the ones who will eventually come to grip with and make adjustments to the realities of the community where they will live.

Whether or not this poor treatment which our own mythology receives is due to the neglect on the part of our educators is hard to judge. Perhaps because we often hear these stories, we rarely pause to consider them important in understanding the nature of Filipino culture and society. Also these oral narratives have become so familiar to us that we often regard them as products of vain imaginings intended to amuse or to frighten a child. If ever we study myths, we view them in terms of what they look like on paper and not in terms-of what they actually serve in life.

Many of us fail to realize that myths fulfill one of the most important functions in society-serving as a means by which people can logically present fundamental concepts of life and systematically express the sentiments which they attach to those concepts. Let us examine briefly how myths supply Filipino institutions (i.e. , family and kindred groups, social; political, and religious) with a retrospective pattern of moral values that makes possible the understanding of the continuity of certain customs and traditions.

Anyone who reads old accounts about the Philippines during the arrival of the Spaniards will certainly note that our forefathers believed in many divinities. These deities inhabited the surrounding world of our ancestors and maintained continued social and ritual interactions with them. Aside from these relationships, these supernatural beings were believed to have control over all phenomena basic to man’s survival-e.g. weather, diseases, success of crops, and so forth-such that every phase of the daily activity had to follow the wishes of these controlling powers. The farmer, the hunter, or the wayfarer venturing into the fields, hills, and forests should first seek the permission of the spirits living in the vicinity or else he would meet with misfortunes on his way.

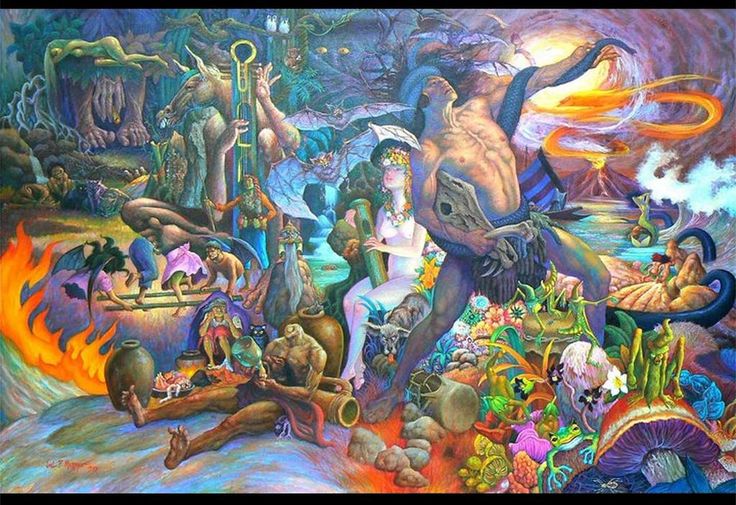

Philippine lower Mythology, showing creatures of the night and deities of the underworld.

In like manner a traveler trodding a new path should first ask the permission of the environmental divinities so that he would arrive safely at his destination. For good harvest hunting fishing building a house, or for any other matter, appropriate sacrifices should be offered to the “soul spirits” of the departed relatives who were considered intercessors with the higher divinities. The offerings should be made during the performance of these proper ceremonies. These diverse ways of establishing relations with the spirit world clearly illustrate how the myths of our ancient fathers, as well as our own today, have favored the growth of traditional beliefs and practices. These also point out to the fact that myths cannot be separated from any social institution as long as human beings are a part of group life.

The nature of human society is such that it requires continuous motivation of human behavior in a culturally constituted behavioral environment, in which traditional meanings of values play a vital role in the organization of needs and goals and in the redirection of immediate experiences. Thus we always find myths and legends identified with the convictions of the group. It is through the elaboration of these folk narratives that ethical and religious views of life assume definite form and character among the people. In like manner, it is from these stories that interpretations of natural phenomena germinate and give rise, unconsciously under the tender care of those who conceived them, to the luxuriant foliage of arts and letters.

Viewed from this perspective, Myths and legends have a far-more-reaching significance than we suppose these have by merely studying the printed text. Perhaps this maybe explicitly stated in terms of how myths play a vital role in the social life of ancient and contemporary Filipinos. It must be realized that myths touch the deepest of human emotions-man’s fears, sentiments, passions, and hopes, as these affect his social activity . They were the first hand tools which man used (and are still using) to justify and validate the social order of his society and to explain his environment, long before any systematic knowledge of natural phenomena became known to him. Their influence has contributed directly to the creation of that great unseen world of ideas and ideals. It was through these narratives that our forefathers defined their world, expressed their feelings, explained their success, and made their judgments. In other words, myths form the fabric of meaning in terms of which our ancestors interpreted their experiences and guided their actions; the source of their realization of how everything they learned had precedents in the past.

Moreover, many of the deified personalities in Filipino mythology were spirits of the departed members of the community. By tracing descent from these divinities, the individual was drawn closer to other members of the group to whom he considered himself related because of common ancestors. In this way, myths of origin endowed our forefathers with a retrospective pattern of historical truth – a living faith which reinforced group solidarity, maintained social order, and made interpersonal relationships easier. The constant repetition of the adventures of culture heroes, moreover, established in the minds of our ancient fathers an effect similar to that which we feel in the study of our contemporary historical heroes. It created in their minds a soil fertile for implanting nobler sentiments necessary to bolster the morale of society and to regulate individual conduct in conformity with the social order of group life. The empirical evidence for this historical assertion lies in the persistence and continuity of Filipino myths and legends among numerous contemporary lowland and mountain groups. The stories recorded by Miguel Lopez de Loarca (1583) and Jose Maria Pavon (1838-39), to cite only two documents, are still currently narrated by the old folk in Western Bisayas.

Thus studied, myths inevitably lead us to a fuller reconstruction of the social context of our prehistoric lifeways and to a better understanding of the details of the historical tradition that form the base of our contemporary culture and society. For one thing, as an eminent anthropologist puts it in wider context, “myths are ways in which the institutions and expectations of the society are emphasized and made dramatic and persuasive in narrative form. Myths show that what a people has to enjoy or endure is right and true – true to the sentiments the people hold.” It is clear then that one cannot hope to understand the Filipinos, as a people, if their tales, myths, legends, and songs, which are part of the matrix of their tradition are disregarded; these native lore give them a sense of being Filipinos.

SOURCE: Outline of Philippine Mythology by F Landa Jocano, Centro Escolar University Research and Development Center, 1969

ALSO READ: Why Isn’t PHILIPPINE MYTHOLOGY Taught in Filipino Grade School?

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.