The Northern Kankana-ey ethnolinguistic group consists of the inhabitants of the municipalities of Sagada and Besao, including those who migrated to other places. Found in the western portion of Mountain Province, these municipalities are bounded on the east by the municipality of Bontoc; on the west by the municipalities of Cervantes and Quirino, Ilocos Sur; on the north by the province of Abra; and on the south by the municipalities of Tadian and Bauko. They are accessible from Baguio through the Halsema Highway or Mountain Trail and from Bontoc through the Bontoc-Sagada road.

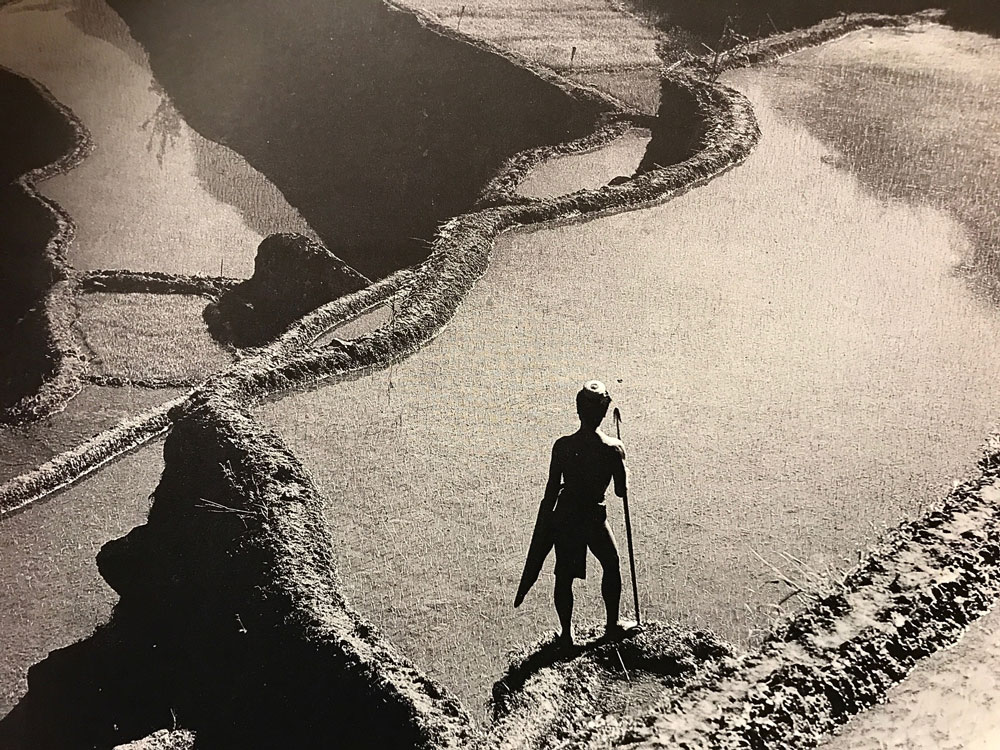

PHOTO: Eduardo Masferré

DNA studies in 2016 show that the Kankana-ey could potentially represent an unadmixed remnant population close to the source that may have given rise to the Austronesian expansion. This could make them among the original ancestors of the Lapita people and modern Polynesians. They might even reflect a better genetic match to the original Austronesian mariners than the aboriginal Taiwanese, the latter being influenced by more recent migrations to Taiwan.

Please note that the following information has been taken from historical studies and may not represent the modern beliefs or the Kankana-ey people or the beliefs of those in Christianized areas.

Religious Beliefs and Rituals of the Northern Kankana-ey

The religion of the Northern Kankana-eys is the worship of ancestors and nature spirits with whom they need to be on excellent terms and which they are careful not to offend. These spirits are the souls of the dead (anitos), and nature spirits. The ancestor spirits are believed to live in the village, especially in rocks and caves, while the nature spirits are believed to dwell in mountains, rocks, trees, or rivers. Moreover, nature spirits are more frequently malevolent, causing sickness or even death to those who disturb their abode. Ancestor spirits are generally good . spirits who are invoked for good health, peace and prosperity. The latter are likewise regarded to have human needs like food and clothing. When they are “cold or hungry,” they make their demands known by making a member of the family become sick. Hence, in all family gatherings requiring the butchering of animals, ancestor spirits are always invited to partake of the food “so that they shall not cause malice to the family.”

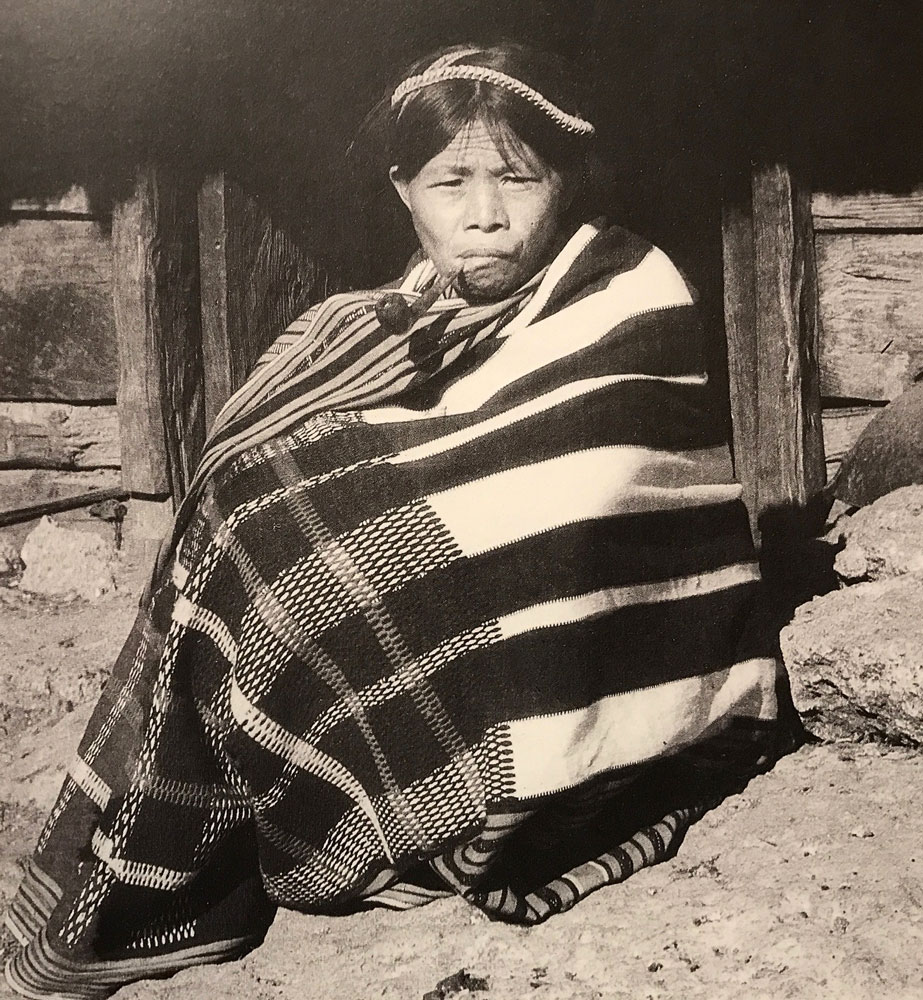

PHOTO: Eduardo Masferré

There also exists a special kind of spirits called pinten, the spirits of men who died a terrible death (e’.g., killed in warfare or accident). They are usually called upon to help for success in headhunting activities or revenge. Even living things like a growing stalk of rice, a rat or a snake are believed to have souls or spirits (ab-abi-ik). A person and his ab-abi-ik are conceived at the same time but when a person dies, the soul continues to live and becomes an anito that dwells in rocks or caves (”Bayang’s Demang Notes” in Philippine Sociological Review 1974:51). The people also believe in a superior deity that they call Kabunian and his son Lumawig, who came down to earth and taught people to live in peace and prosperity.

A feast and sacrifices of food and wine are used to gain the favor of the spirits (except for Lumawig who is not given to any sacrifices) who are called to cure an illness, to give a bountiful harvest, to counteract bad omens, etc. Salted pork and chicken are the most common sacrifices although dogs and carabaos may also be used. Carabaos are sacrificed only for wedding feasts while dogs are offered in ceremonies connected with headhunting. Unlike the Ibaloys who have ordained priests that officiate in ceremonies, the Northern Kankana-eys have none. Any experienced old man recites the prayers usually from memory, and it is he who also inspects the bile sac or liver and interprets it (mamidis).

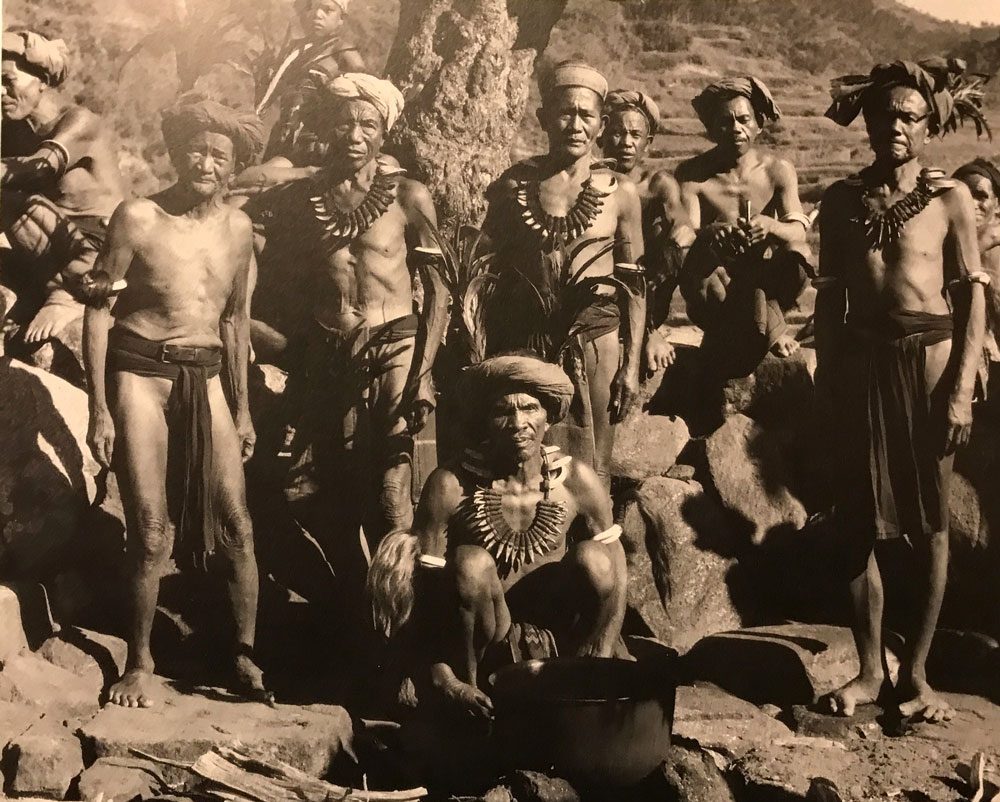

PHOTO: Eduardo Masferré

Supernatural Beliefs and Omens of the Northern Kankana-ey.

These play a major role in the religious life of the Northern Kankana-eys. For example, whenever a person travels to another place, he must first kill a chicken and inspect its liver (pidis). He continues on the journey if the pidis is favorable; otherwise, he delays the trip or butchers another chicken before he proceeds. And when he is on the way and a bird of any kind flies across the trail ahead of him, he must not continue for he might not be able to accomplish his mission or he might get into trouble. But if the trip is of outmost importance to him that he needs to go without delay, he stops right at the place where the bird crossed and stays there for about half an hour or he must retrace his’ steps and make a new start. A rat ·or a snake crossing his path is also considered a bad sign. If a man has started building a house, he is altogether prohibited to go on a journey until the house is completed (Robertson 1914:484, 486, 509). Also, the appearance of a rainbow or the occurrence of an earthquake during the performance of rituals is a bad omen. The ritual has to be performed all over again on a scheduled day when any of these two bad signs is observed.

PHOTO: Eduardo Masferré

The people are always careful to heed these omens otherwise misfortune shall befall them. Sometimes, they resort to the performance of special rituals to counteract bad signs.

Dap-ay or Abong.

The dap-ay is a political, religious and social institution as in the Bontoc ethnolinguistic group. It serves as the center of all religious rites, a gathering place to meet and settle disputes, hold meetings, and a place for men and boys to sleep at night. It is also a place where young boys are given lessons on discipline and where customs, traditions and taboos are also taught. In the days of active raiding and headhunting, the dap-ay also served as a unit for guarding and protection.

PHOTO: Eduardo Masferré

The dap-ay is composed of families (average of 25 households) with the male members representing their respective families in political and ceremonial matters. Each dap-ay has a certain degree of autonomy but it cooperates closely with the other dap-ays for the welfare of the whole village.

Source: Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera, Cordillera Schools Group, Inc., New Day Publishers, 2003

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.