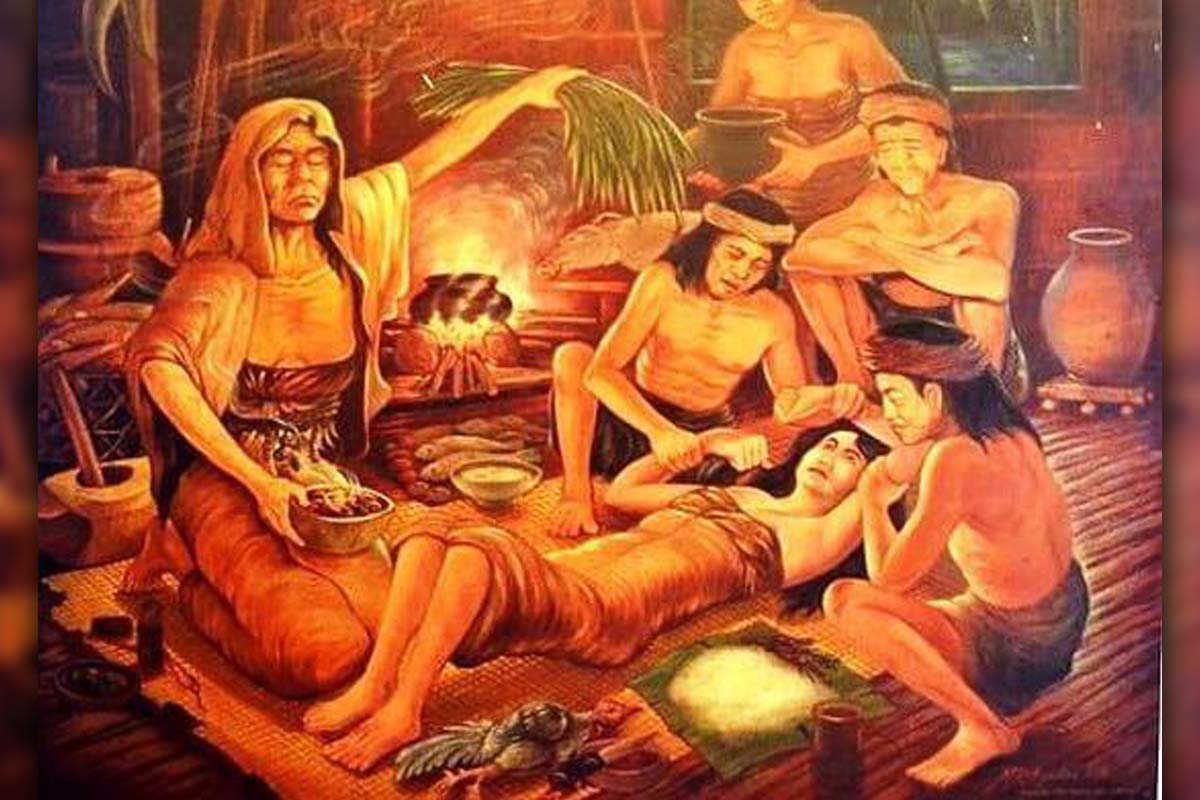

Babaylan were shamans of the various ethnic groups of the pre-colonial Philippine islands. These shamans specialized in communicating, appeasing, or harnessing the spirits of the dead and the spirits of nature. Much of what we know about the babaylan is from information gathered by chroniclers after the first Spanish-Filipino contact in 1521.

When trying to determine the gender of the babaylan, we often consider three occurrences which are all supported by historical fact. The first is that the role of babaylan was one that females took on. This is supported throughout the Blair and Robertson compilation of historical accounts. Particularly we can look at the documentation of these “women” by Captain Diego Artieda in 1569-70 and by Miguel de Loarca in 1582-83 where they were described as a “priestess” in the Visayas. The second notion is that this role was traditionally held by what we may consider today as “transgender females”. This is where the documentation becomes very interesting. Fray Domingo Perez, OP. noted in 1609-1616 in Zambales “The priest called the bayoc” who dresses like a woman, and The Boxer Codex (written in 1595) noted a similar occurrence in the Tagalog region, “They are so effeminate that one who did not know them would believe that they were women.” Still, it wasn’t until 1668 that Alcina noted this in the Visayas – “there were native Visayan priests called asogs who were also hermaphrodites.” The third occurrence that needs to be considered is how most of the folk healers and babaylan on Panay today are men. This can best be highlighted through the work of Alicia P. Magos and her recent fieldwork documenting the Sugidnon Epics as well as in her work on the Ma-aram traditions in a Kinaray-a Village. It was also mentioned in The Boxer Codex that the Tagalog shaman (catalonan) was male or female. We also can’t ignore that there is documentation by Diego de Bobadilla in 1638-1640 showing that there were in fact also male babaylans.

I feel a lot of people approach this subject with an agenda to show that there were both male and female babaylan, that the role belonged historically to women, or that it historically belonged to transgender women. Commonly we will see the feminist movement highlighting incidents where the Spanish violently ripped the female babaylan or catalonan from power. We have LBGTQIA+ communities focusing on the above historical facts that support the notion transgender people performed this function. So which is the truth? Any reasonable researcher would likely surmise that it is all the truth. We can attribute much of this to the simple fact that each region of the Philippines underwent their own evolution, but there would need to be a conclusion to explain the discrepancies documented in a particular region. We need to explore “why” it is all the truth. In the case of Panay:

1569-90 – babaylan were documented as women

1582-83 – babaylan were documented as women

1688 – babaylan were documented as ‘transgender women’ (modern term)

17th – 19th century – revolts led by male babaylan

1980’s – babaylan are predominantly male

I’ve read several conclusions that state the ‘transgender female’ babaylan was so convincing that the Spanish chroniclers thought they were women. With the Boxer Codex backing this notion up, it has become a non-academically accepted theory with a troubling timeline when looking at Visayan history and the documentation that exists. Maria Milagros Geremia-Lachica presents a much more plausible explanation in her excellent 1996 paper “Panay’s Babaylan: The Male Takeover” presented in The Review of Women’s Studies.

Panay’s Babaylan: The Male Takeover

by Maria Milagros Geremia-Lachica

The Blair and Robertson compilation of historical accounts woven by the Spanish friars unfolds a rich tapestry of the early Filipino way of life and their form of worship. Spun in devil-dark threads were accounts of the native priestesses or babaylanes.

From the closing decades of the 16th century up to the early 1900s, Panay island in Central Philippines was disturbed by uprisings led by the babaylanes against the missionaries. Friars assigned in different parts of the island were poisoned or speared to death. Fray Juan Fernandez in his annotations identified the interior towns like Lambunao and Tubungan in Iloilo and Antique province as the stronghold of babaylanes.

Also known as dailan (from dait which means friendship/peace), the babaylan was mediator between the gods and the people and healer of the body and spirit. Mostly played by women, the babaylan’s role bordered on the political as well, being a close adviser of the datu in almost all matters concerning religion, medicine, natural phenomena, etc. (Alcina trans. Lietz, 1960:212).

According to Alfred McCoy, “babaylan” is from a classical Malay word “belian”, “balian” or “waylan” of Java, Bali, Borneo and Kalmahera which means “spirit medium”. The commonality between the southeast Asian and Panay babaylan is not only in the root word of the terms but also in their rituals and roles in society ( 1982: 144 ).

To be a babaylan is a gift to the person chosen by the spirit. This choice is manifested in dreams, visions, a lingering illness or strange events happening to the chosen one. The babaylan has the power to communicate to ancestral and environmental spirits and thus able to bargain or cajole the spirits for a person’s captured dungan. In Panay, the dungan is a traditional concept which loosely means a person’s soul or “double”. A person is considered healthy when his dungan is properly nurtured and strengthened. However, spirits may capture or play with a person’s dungan, causing the person to become sick (Magos:1990:6).

The Hiligaynon “babayi” for woman shows a close relation to the term “babaylan”. In Kinaray-a, an ancient language still being spoken in Antique and some interior towns of Iloilo, “bayi” and “bay/an” are the terms used. In Kinaray-a, “bayi” is also used to refer to one’s female grand elders. “Babaylan” then implies an age-old tradition embodied in the concepts basic to the culture and society of Panay.

Woman: The Babaylan

With the colonial rule came the Roman Catholic religion which resulted in the persecution of the native priestesses and their followers. According to Fray Diego Aduarte, the babaylanes were punished and their idols were confiscated and burned with the intention of wiping out their pagan practices. Nevertheless, vestiges of the native religion persisted and its followers troubled the ecclesiastical and civil authorities.

In 1580-1590, when Muslims invaded Panay, babaylanes like Dupinagay (or Dupangay), Monica Gapon and Augustina Hiticon took advantage of the situation. They rallied the people to return to their native faith but their efforts failed. From the early 17th to the late 18th century, a series of babaylan uprisings occurred in various parts of Panay but Antique was supposed to be where they originated and the province was earlier identified as the “hotbed” of babaylan practices. It was reported that 180 “diabolical women” gathered in the closing part of the 18th century to preach the old faith and disturbed the town of Sibalom (Fernandez trans. Arias, 1965:343).

Historical accounts reveal that traditional babaylan leaders were predominantly women. Notable among the babaylanes in Panay during the second half of the 19th century was Estrella Bangotbanwa. Believed to possess supernatural powers, Estrella gained a sizable following as rite-officiator to ensure favorable weather for a bountiful harvest. She was considered as “Tagsagod kang Kalibutan” or “Caretaker of the World” (Vicente, Interview: 1995). Her most dramatic feat was when she performed a ritual to summon heavy rains which ended the three year drought in the towns of Miagao and San Joaquin, Iloilo (Magos, 1990:35). To this day, babaylanes still invoke Estrella’s name in their rituals.

A close look at the term “babaylan” indicates that it is identified with the female gender. “Babaylan” could be further interpreted as a corruption of two local terms: “babayi lang“-“woman only” which imply the gender-exclusive role of females as traditional rite-officiators and religious leaders. Hence, “babaylan” or a sisterhood of women with very special powers.

Asog: The Male Babaylan

In his report on the Bisayans in the Samar-Leyte area, Fray Alcina noted that priests and sacrificers were commonly women, but there were also some male babaylanes:

.. .if there were some man who might have been one, he was asog

… (Alcina trans Lietz, 1960:212)

Fray Fernandez also mentioned Tapara, an asog or male babaylan of Lambunao, Iloilo who dressed and acted like a female. Fray Alcina further explained the asog as:

.. .impotent men and deficient for the practice of matrimony, considered themselves more like women than men in their manner of living or going about, even in their occupations …

Though the term might sound alien to the younger generation, it is interesting to note that “asog” is still being used by older folks today to refer not to men but to sterile or barren women (Mulato, Interview 1996). In contemporary Hiligaynon, farmers use the term “asog” to refer only to female animals which are unproductive (Reforma, Interview: 1994). An out-of-print Visayan-English dictionary has a similar meaning. In Aklan province, the term refers to a female acting like a male or a “tomboy” (Geremia, Interview: 1996).

In today’s context, a more appropriate term for a male who dresses and acts like a female is “agi”, “bakla” or “gay“. Perhaps the friar chroniclers were mistaken but they were recorders of a folk perception. The folk may have chosen a supposedly female adjective to describe this kind of male babaylan because he was perceived to be more female in manner and appearance. From a folk perspective, the term “asog” then raises two points: the female gender as its basis and sterility. The asog may be female-like but not a true female where fertility is concerned. This implies that “babaylan” describes the biologically female who has a womb and therefore capable of producing an offspring. On the other hand, “asog” describes a biologically male babaylan who apes a female’s outward characteristics. If “asog” refers to the inability to reproduce or give birth, then it is also an apt term for describing the male babaylan who has no womb and therefore, can never bear children.

In his notes on the Sambals, Fray Domingo Perez mentioned about male priests called bayoc who dressed like females. The term bayoc is close to the Cebuano “bayot” which refers to a male homosexual. Did the “agi” or “bayoc” define a male gender which was more female-like? Did the “agi” or “bayot” perhaps evolve from this asog or bayoc gender phenomenon of the babaylan? The asog or bayoc concept further raises more tickling questions. What was the folk perception of male homosexuality? Was male homosexuality accepted and tolerated in early Filipino society because of its link to the babaylan role? Is it because of this cultural link in the past that Filipino male homosexuals today tend to have closer friendly ties with females?

According to Alcina, the asog was considered deficient in the performance of his role as a male and thus deficient for matrimony. This might have lowered his worth or value in a society which expects males to enter matrimony and beget children. But it was also this deficiency his being more female which qualified him into the babaylan sisterhood. As a babaylan, the asog raises his worth and gains honor in a society which might have been unwelcome for his kind.

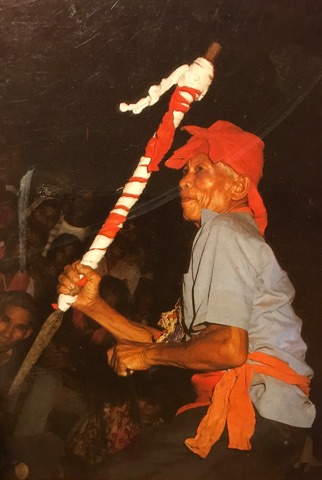

Researcher Alfred McCoy did not mention the asog but he took note of two babaylan leaders who were reputed to be homosexuals. Ponciano Elofre, who was also known as “Buhawi” (God of the Four Winds) led one of the earliest of major revolts in 1887-1890 in Negros Island. In 1897, Gregorio Lampinio of Lambuanao, Iloilo joined the pulahan group of Hermenegildo Maraingan who attacked some towns in Capiz. Lampinio was a homosexual and one of Maraingan’s influential secondary leaders.

Unlike the Japanese who had no distinct label for their male shaman, (Hori, 1983: 181) the “asog” might qualify as Panay’s distinguishing term for the male babaylan. With the “asog” concept, the babaylan “babayi lang” ended its being an exclusive sisterhood. The entry of the male gender through the asog phenomenon and his eventual acceptance as babaylan perhaps served as a transition for the eventual male babaylan “takeover”.

Where Were the Women?

A review of babaylan-led revolts against the colonizers reveals a succession of male leaders from Gregorio “Dios” in 1888 to Papa Isio in 1901 (McCoy: 1982). On the other hand, female leaders were unheard of except for Estrella Bangotbanwa who was remembered for her supernatural powers as rite-officiator than for leading an armed revolt. What happened to women, the original babaylanes?

It was perhaps the stiff rivalry between the male-led Catholic religion and the native faith which “ousted” the female babaylanes. The natives had to look for a religious leader parallel to the priest and the female babaylan was not the answer. She may have had a strong following as a leader but she was not male like the friar. This might explain a sort of a folk compromise in the asog who was biologically male like the priest but possessing female qualities of the original babaylan. Hence the asog’s acceptance as the babaylan until the natives saw the urgent need for a warrior leader. It was a period of persecution for the babaylanes who refused to give up their traditional faith and the natives were beginning to rebel against the heaviness of the colonial yoke. Aside from the crisis of war, there were epidemics and natural calamities which threatened the very lives of the natives. With his gift of healing, supernatural powers and the capability to lead and wage war, the male babaylan non-asog warrior eventually emerged and took over. Thus all revolts of babaylanes against the colonizers were led by the males.

Today, the babaylan tradition is still being kept alive with males in the lead. The male babaylanes today are not called asog anymore but they still wear the robe or a skirt-like garment when they perform their rituals. Like the asog in the past, is the male babaylan dressed like a female to acknowledge the woman-exclusive, original babaylan? What is in the woman? Is it because she has womb? Is it because she bleeds?

Because of the Womb

According to Victor Turner, blood is a multi-vocal symbol (cited by Helman, 1986: 19) and also the most potent symbol of life (Kupfermann, 1979:53). A woman who menstruates signals her readiness to bring forth and nurture new life, an important yet mysterious power of women. Because of her womb, woman is life-giver-nurturer and her bleedings signify her power upon which the fundamental concept of existence and continuity of a tribe or community depends. However, a woman’s bleedings also imply an ambivalence. If she possesses that life-giving potential, she also carries that threat to society’s existence. As Valerio Valeri points out:

… these bleedings are the internal becoming the external, the normally hidden and therefore mysterious generative power of women

made visible …

The womb which is her very strength becomes a liability since its vulnerability is exposed each time she menstruates. Bleeding women reveal their helplessness to control their own generative power. This helplessness is also shared by men whose very existence is dependent on women’s womb-power. In central Panay, the local term for menstruation is “paramulanun” or “monthlies” from “bulan” to mean the moon or month. That the local term for menstruation is associated with the moon further supports Valeri’s hypothesis that:

… the phenomena of female fertility, just like motions of the celestial bodies, is viewed as uncontrollable. That the connection with the lunar cycle reveals another feature of the life-giving power in women’s wombs: that it is inextricably connected with death

(1990:262).

The periodicity of the menses is likened to the moon’s waxing and waning which signifies birth and death. Like her bleedings, woman becomes a paradoxical symbol of life and death.

Women may have the womb and they alone possess the power to bring forth new life but along with this is always a threat of the loss of this power. As such, the absence of female babaylanes in revolts was perhaps not so much in protection of women as life-givers but also more to hide the tribe’s vulnerability. In her public role as babaylan, woman’s womb and her role as life-giver-nurturer of the tribe or society was also made public. As a babaylan, the tribe or society was constantly confronted with the possible loss of her generative power. Because of thei public role, the loss of women’s generative power may also mean the weakening and eventual death of a tribe or society. Thus she has to cease becoming a public figure and the powerful woman-exclusive “babayi lang” or “woman only” is given another reading to connote weakness which displaces her in the lead role. However, she remains a potent force in the background, always ready for the moment when she is needed once again as a life-giver.

– END OF PAPER by Maria Milagros Geremia-Lachica –

In Conclusion

While the above theory is just that – a theory, it does effectively explain the evolution from female to male babaylan over the course of Spanish rule on Panay Island. More importantly, for me, it creates a plausible timeline and supports the intentions of other theories previously presented. It highlights the historical importance that all gender identities played in this evolution – female, male, gay, trans. It is the acceptance and value placed on all of these gender identities that managed to keep tradition alive through the most culturally disruptive portion of the archipelago’s history. We could potentially apply similar theories to areas of Islamic influence, but it would seem to fall apart when examining the male dominated priesthood in the Ifugao areas. It’s a fascinating topic and I hope others will expand on this research and share their theories and ideas on The Aswang Project Facebook page.

SOURCES CITED

Aduarte, Diego. The Philippine Island, 1493-I898. Vol. 30. Emma Blair and John Alexander Robertson, eds. Cleveland, Ohio: The A.H. Clark Publishing Company, 1903-1909. pp, 285-298.

Aleina, Francisco Ignacio. Historia de Los Islas y Indios de Bisayas, 1668 (History of the Island and Indios of the Bisayas), Part I, book 4, Trans. Paul Lietz University of Chicago, 1960.

Fernandez, Juan. “Historical Annotations on the Island of Panay”. Trans. Edgardo S. Arias. Jaro, Iloilo City: Central Philippine University, 1965.

Helman, Cecil. Cultural Health and Illness. England, John Wright and Sons Ltd., 1986.

Hori, Ichiro. Folk Religion in Japan: Continuity and Charge. Joseph M.

Kitagawa and Alan L. Miller, eds. Chicago University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Kaufmann, J. M.H.M. Visayan-English Dictionary. Iloilo: La Editorial Press, 1935.

Kupfermann, Jeanette. The MsTaken Body. New York: Granada Publication Ltd., 1981.

Magos, Alicia P. The Enduring Ma-aram Tradition. Quezon City: New Day Publisher, 1992.

McCoy, Alfred. “Baylan Animist Religion and Philippine Peasant Ideology”. Philippines Quarterly of Culture and Society. Vol. 10, 1982.

Perez, Domingo. The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898. Vol. 47. Emma Blair and

John Alexander Robertson, eds. Cleveland, Ohio. The A.H. Clark Publishing Company, 1903-1909. pp. 298-307.

Valeri, Valerio. “Reflections on Menstrual and Parturitional Taboos in Huaulu Seram” in Power and Difference. Jane M. Atkinson and Shelley Errington, eds. U.S.A.: Stanford University Press, 1990).

INTERVIEWS

Geremia, Lolita, 65 yrs. old ret. school nurse, Sibalom, Antique, Feb. 1996.

Mulato, Santiago, 80 yrs. old, Hiligaynon lexicographer, Iloilo City April 1996.

Reforma, Rolando, 40 yrs. old, cattle buyer, Molo, Iloilo City, Sept. 1994.

Vicente, Lucibar, 84 yrs. old, farmer, Sibalom, Antique, June 1994.

ALSO READ: Were Babaylans “Chopped Up and Fed to the Crocodiles” by the Spanish?

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.