Since completing The Aswang Phenomenon documentary in 2011 and launching The Aswang Project blog last year, I have been met with overwhelmingly positive feedback. Young Filipinos all over the world have reached out to me in appreciation for giving them a place to learn about other aspects of their cultural identity. I should mention that, as an outsider, I have also learned an equal amount from their stories and input. It isn’t all positive, I’ve also received my share of hate mail calling the project “stupid” and a “waste of time”. There were two people who even threaten to start a campaign to shut it down. Luckily, I am not beholden to any government funding or investors and what I do with my time and money is my own business – and I choose to explore Philippine Folklore and Mythology.

The Spanish Demonization

The true Spanish contribution to folkloric creatures was teaching Filipinos that they were inferior and stupid for including them as part of their culture.

First, I need to say that the Spanish were responsible for destroying polytheism in the Philippines – often with brutal and forceful tactics. Their list of crimes against Filipino culture is endless, but inventing the creatures of Philippine mythology was not one of them. “The Spanish invented mythical creatures to keep us afrad” is the statement I am always given regarding the monsters of the Philippines. This sentiment seems to have appeared from nowhere and been backed up by nothing, yet has become indelible thinking. Yes, they classified the babaylan and catalonans as witches. Yes, they mis-classified ‘some’ of the Tagalog gods as witches (read more), but they did not invent the creatures.

Philippine history is beholden to oral stories by Filipinos and documentation by the Spanish. Without reading the volumes of historical letters written by the Spanish (which I have), presumptuous statements are easy to make. The Spanish documented much of their brutalization of the “natives.”. So this conspiracy theory that they secretly created a pantheon of mythical creatures to control the people is not based on anything but speculation. To the contrary, belief in these beings was constantly documented as a great frustration. The friars were completely powerless in eliminating this aspect of of the ancient belief structure.

If one spends the time to read these documents, they will see that the aswang, tikbalang, tiyanak, and other “black spirits” were among Filipino beliefs when the Spanish arrived, during colonization, and until today. As with most polytheistic mythology – including Norse, Japanese (kami-no-michi), and Greek – folkloric beings pre-date the gods and were included as part of the mythology. The Philippines is no exception to this steadfast pattern. Animism pre-dates ALL religion.

The true Spanish contribution to folkloric creatures was teaching Filipinos that they were inferior and stupid for including them as part of their culture. This is the Spanish legacy regarding these beings, and this thinking has endured. The fact that these folkloric creatures have survived all these years under such oppressive thinking is a testament to their cultural relevance. The damage caused by the Spanish is not just the demolishing of folkloric culture, but the ingrained and persistently negative thinking towards it.

The most devout Filipino Catholic will still put salt in their doorway to stop an engkanto from entering. This isn’t the will of the Spanish, but the remainder of what survived their colonization. These beliefs transcended 400 years of colonial occupation, why would you want to give that away?

Culture, as taught by Regal Films

Every movie needs a hero and a villain. I applaud Regal Films for bringing these folkloric creatures into the mainstream, but without an ingrained cultural bearing, they have been turned into the cold-blooded, indiscriminate murderers they are portrayed on screen as. Folkloric creatures can be benevolent, malevolent, or neutral, but almost always with purpose. Historically, they explained a natural occurrence – such as death, miscarriage, or illness. The creatures of Shake, Rattle & Roll are antagonists created and borrowed by artists to push a story forward. Instead of creating a Jason Voorhees or Freddy Krueger, Regal simply used the existing image of the Aswang.

Don’t get me wrong, I LOVE Regal horror films, but I find it tragic that there is nothing to culturally balance out the blood-thirsty images on screen. Instead, these murderous portrayals became the norm. Since Regal horror films were marketed to the largest societal class, the content they displayed was unfairly judged as something “beneath” other societal classes.

This is amplified, when Filipino families immigrate to other countries. There seems to be such a rush to assimilate that anything uniquely Filipino, aside from food, is abandoned within a generation.

United we argue, divided we argue

The Americans unintentionally finished what the Spanish began.

I don’t think there is any need for me to go into great length about the Americanization of Philippine culture. However, I will point out something very interesting that happened around the turn of the 20th century just after the Spanish American War. When education was made available to all Filipinos and the country was opened up to American scholars, we were given 30- 50 years of incredible anthropological studies on the people of the Philippines who were not successfully colonized (the “tribes”). Unsurprisingly (to me), the aswang, and other folkloric demons, spirits and beings are all there among the various beliefs. What comes as a complete surprise, is that none of these incredible studies are part of public education.

The Americans unintentionally finished what the Spanish began. There seems to have been a disconnect between the American academic community studying about the Philippines and the ones dictating educational policy. Since American culture (aside from native beliefs) contains no folkloric history, it was not included as part of the new public education structure in the Philippines. Instead, Americanization enforced the same abysmal treatment of indigenous culture in the Philippines, as was previously seen in the US. To this day, in the Philippines, exploration of cultural identity is something reserved for the upper class or those lucky enough to attend one of the prominent universities. Even then, it is only explored if one chooses to.

I’m not saying all public schools need to contain a course called “aswang”, but cultural beliefs and practices – even the ‘ugly’ ones – should be recognized by the government and included. Congress recently approved the final version of the Integrated History Act of 2016 which mandates the integration of Filipino-Muslim and indigenous people’s history, culture, and identity in the study of Philippine history in both basic and higher education. I remain hopeful that this will be enacted nation-wide and serve its intended purpose.

To complicate things, you have people who choose to fully embrace and blanketly apply any positive telling of Filipino culture from historical documents – herbal remedies, gender identity, trade, warrior classes, etc. At the same time, they completely reject anything negative from those same documents – slavery, misogyny, and creatures. On top of this, there is a growing collective that is completely rejecting all documentation by the Spanish and Westerners – even going as far as rejecting the term”Filipino”. There is tremendous value in oral folklore, but it is adaptive by nature. Historical accuracy lies somewhere in-between these stances – if you approach all of them all with an equal view. As it is, the bickering that goes on between these groups leaves an even more complex path to navigate.

Learning by Example

The Yōkai are a class of supernatural monsters, spirits and demons in Japanese folklore. They have been featured in movies, TV shows, animated series and manga – from all out horror to children’s stories. Unlike the Philippines though, they are culturally recognized as part of history by Japanese folklorists, historians, and the government. Yōkai usually have a spiritual supernatural power. There are a large number of yōkai who were originally ordinary human beings, transformed into something horrific and grotesque during an extremely emotional state. Women suffering from intense jealousy, for example, were thought to transform into the female oni – which has traits of demons and ogres, a wide mouth filled with fangs, and depicted as evil. Many indigenous Japanese animals are thought to have magical qualities. Most of these are henge, which are shapeshifters (o-bake, bake-mono) that often appear in human form.

Any of this sounding familiar? These folkloric creatures have existed and been documented in Japan since the first century – all without the help of the Spanish. The same can be said for folkloric beings in China, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

In addition to the essential educational subjects, Japanese children are taught lessons that develop several themes put forth by the National Council for the Social Studies curriculum standards, including Culture, Individual Development and Identity. This isn’t to say Japan should be used as an educational guideline for the Philippines, but its approach to preservation of historical cultural beliefs and identity should. Because there are multitudes of educational materials surrounding Japanese mythology, it no longer has a stronghold over the people. It has been accepted and celebrated as part of the cultural past. This is what I would hope to see in the Philippines, because anyone who takes the journey into The Creatures of Philippine Mythology will find that it is a unique and intensely Filipino experience.

Filipinos have beautiful family values, wonderful food, unparalleled hospitality, and a wicked sense of humour, but (to this outsider) it sometimes feels like a nation without an ingrained cultural identity. Before you argue me on this point, ask yourself what makes you culturally proud to be Filipino. Then ask someone else and see if you get a similar answer. Until this is corrected I believe the Philippines will continue to see value placed on the individual achievements of others instead of collective achievements as a country. We will continue to see celebrity culture glorified and one’s personal worth placed on whether a boxer, singer, or beauty queen wins their contest.

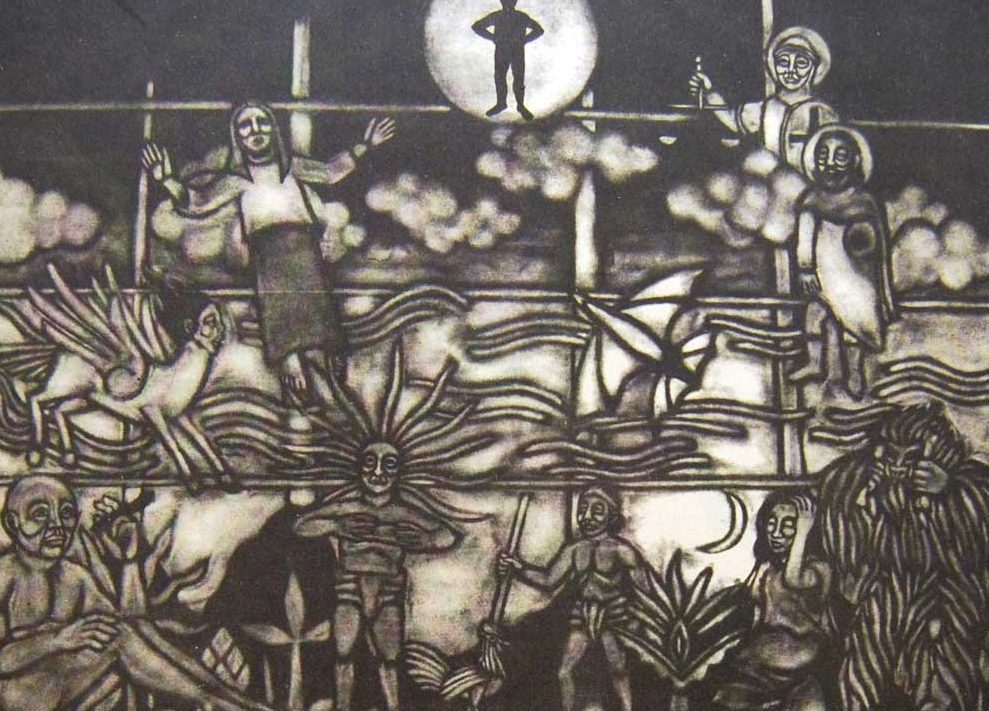

The simple act of bringing folkloric beings into the classroom sends the message that the Filipino identity is connected to the past – a folkloric past that existed before Magellan and survived until today. These mythical beings and the cultural practices they employ are actually one of the very few things that did survive colonialism. Although each region does not share the exact same traditions, they share an ancient identity with folkloric creatures that only vary slightly around the archipelago. And that just adds up to good social studies.

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.