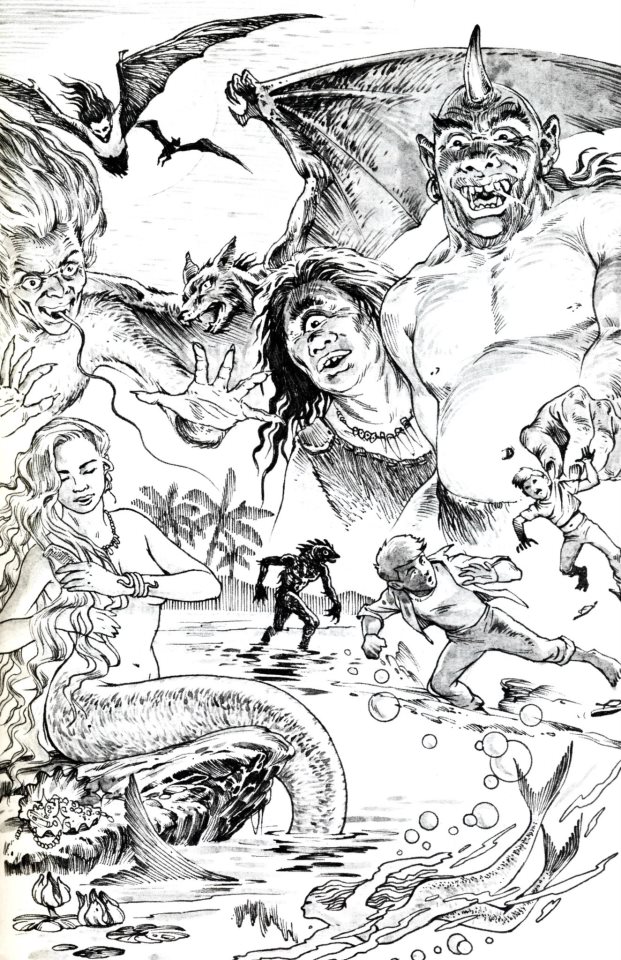

We may all be familiar with the term “tabi tabi po”, which is used when someone is entering a locale where Philippine folkloric spirits may be living. It is a way of saying “excuse me” or “pardon me” for fear the beings may inflict upon you some illness, fever, rash or other malady if they are not acknowledged or given respect. Tabi tabi po has also be translated as “move to the side, sir”. This term is pretty much the only one we usually hear about. As someone who travels all over the Philippines, I thought I’d ask if there are any other terms I might need to know. After all, it is believed you may possibly offend a spirit if you spit on the ground, urinate on the ground, walk near a dirt mound, pass under (or near) a balete tree, bathe or cross through (or near) water,step on a rock, or move through tall grass.

The term being used as one of deference was first recorded by Pigafetta in his account of Magellan’s voyage (1524), although it is likely much older. “Abong was an honor a datu might pay one of his timawa vassals by presenting his own cup after he had taken a few sips himself. Sumsum was any food taken with the wine (that is, pulotan), like the plate o f pork Rajah Kolambu shared with Pigafetta who reported, “We took a cup with every mouthful.” And had Pigafetta been a Visayan, he would have murmured politely with each piece, “Tabi-tabi dinyo [By your leave, sir].”

Fray Alonso de Méntrida also documented this practice in 1637: And everybody addressed seniors or respected persons with polite tabi expressions like “Tabi sa iyo umagi ako [With your permission, I will pass]”.

Today, this polite respect is more associated with the invisible. “Tabi, tabi po baka kayo mabunggd” (Excuse me, please, lest I bump you) is the polite way to pass. Now shortened to “tabi tabi po”.

So let’s say you are in LEYTE and are passing by the suspected dwelling place of an AGTA, the supernatural man of dark complexion and extraordinary size inhabiting trees, cliffs, or empty houses. Tabi tabi po may be alright since the appropriate saying to pass by is “Tabi apoy”. Unless of course the situation would require you to use the longer “Tabi-tabi, purya buyag”.

However, when travelling through the ILOCOS REGION you might want to avoid the MANGMANGKIT, an invisible tree spirit. They are particularly known for being upset when their tree-home is felled without permission. Or perhaps you wanted to take precautions while sleeping near a wooden post in case the BATIBAT decided to haunt your dreams. Someone from Manila might use “tabi tabi po”, although the correct saying would be “kayu kayu”. You may also use “bari bari” if you’re asking the spirit of a dead person to spare you from notice. It it is also normal to matter-of-factly announce to no-one, “magmagná, apo!”

I posed a question on THE ASWANG PROJECT Facebook Page to find out some other terms that are used around the country. Here are the answers:

CEBU: “Paagi-a” or “paagi a’ mi”

PAMPANGA: “Bari bari apu” or “makilabas ke pu”

BICOL: “tabi apo”

ILIGAN: we use “tabi apo, makiagi lang” or just “tabi apo”.

DAVAO DEL SUR: “tabi tabi tabi”

DIPOLOG CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE: “Tabi-a po, tabi-a po!”

ORMOC, LEYTE: “tabi tawn” or “buyag tawn”

BANTON, ROMBLON: “Tabi Tabi, Marayan Anay” (Tabi Tabi Padaan Muna)

CATARMAN, SAMAR: “Tabi baba”

NEGROS: “Tabi tabi malabay or tabi, tabi buyag”

ALBAY: “Tabi apo”

Facebook user Jb Greek had some detailed advice for those visiting BULAN, SORSOGON. “In my home barangay, we say, “makiagi tabi” which means “excuse me/us, may I/we pass by please” when we are passing by a place which believed to be a dwelling place for engkatados. We say “tabi, pwera ila”which means “please spare us from enchantment” when we see, smell, hear or feel something supernatural to avoid from being enchanted, we say, “tabi, tabi, buta kami, kamo diri” which means “excuse me/us, excuse me/us, I am/we are blind but you are not” or simply “excuse me/us, I/we don’t see you” . When we do something naman which we think would disturb engkatados’ dwelling place like throwing something in the dark or peeing anywhere. We also say, “tabi, pwera gabos” which means “excuse me/us, spare me/us from all (bad things)”. Or, generally, we just simply say, “TABI, TABI!”

While I was visiting the Batak Tribe on Palawan, there was a very serious illness making its way through the village. It had already taken the life of a baby and a elder. The people believed that a ‘diwata’ in the river had infected the children who were playing there at 12 noon some days before, as they were the first infected. The village is located on a bend of the river and spans several hundred meters along its bank. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that some waterborne bacteria was introduced up stream, or was present in a calmer section. Still, while the villagers relied on modern medicine to heal themselves, the river was eerily empty during the peak diwata hours of 12-3pm. To get to and from the village, it is required to cross this winding river 10 times. Upon each crossing, my very well educated guide would say “tabi, tabi, tabi.”

It seems that “tabi” is a common element, but is the following term of respect equally important, or do these folkloric beings understand the intent? I’ve noticed that some places say “tabi, tabi, tabi”, using the term three times. I also received a comment saying “Tabi-tabi po, lolo po 3X or Bari-bari-bari 3X”. Is the amount of times it is said also important? I’ve been lucky enough to visit a few countries around the world, and many different provinces throughout the Philippines. Learning common courtesies in the local language goes a long way with the people. I have no reason to think that folkloric spirits would be any different.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES:

Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society, William Henry Scott, Ateneo Press (1994)

THE SOUL BOOK, Demetrio, Coredero-Fernando, Zialcita, GCF Books 1990

The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology, Maximo D. Ramos, Phoenix Publishing 1990

ALSO READ: BIANGONAN | Welcome To Your New Nightmare, Batak Folklore

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.