I had a very interesting discussion with a bright young man in the Center for Paranormal Studies Facebook Group. He asked, “ I am wondering why there is such as thing as lower Myth. I am sure U are familiar with the Hero’s Journey and I am not really sure if there is a lower myth in this case. Jung never mentioned a lower myth or anyone who follows their lead.”

To answer his question, , the theory of “lower mythology”, or the “demonological theory” represent myths as “a reflection of everyday phenomena”. The theory was advanced by German scholars F.L.W. Schwartz and W. Mannhardt. The academic work done on lower mythology started while mapping the mythic structures of early Indo-Germanic Tribes and was used with many Indo-European mythological studies. “Lower Mythology” was a classification created to help map extremely complex mythic structures. With the advances in understanding early belief structures, it is no longer a recognized classification when studying mythical beings in folklore around the world. This, for some reason, is not the case in the Philippines.

What constitutes a creature of lower mythology?

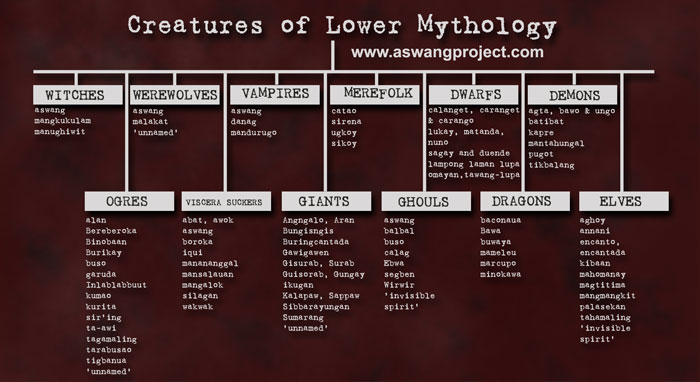

In short, creatures of lower mythology consist of beings that have no objective reality yet are regarded in folk traditions to actually exist. They are generally up to no good, and usually rank below spirits, angels, dieties, and ghosts. In many belief structures, these creatures take up residence in water, trees, rocks or hide in human form. For instance, early studies on Norse Mythology classified Dökkálfar (dark elves) as “lower” creatures because they are not a God or Giant. In the case of the Philippines, this classification was attributed to creatures such as the aswang, tikbalang, kapre, batibat etc.

The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology by Dr. Maximo Ramos

Dr. Maximo Ramos completed his Ph.D dissertation on the Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology under the guidance of Wayland D. Hand – the former President of The American Folklore Society and former Director of the Center for Comparative Folklore and Mythology at the University of California. Despite Ramos’ invaluable contribution to the preservation and documentation of these creatures, I need to point out his error in using the terms “higher” and “lower” mythology. Dr. Ramos used the terms to help separate the ghouls from the gods, and in the context of his dissertation, it was wonderfully effective. However, in the context of understanding Philippine Mythology, it is confusing – not to mention outdated (even at the time).

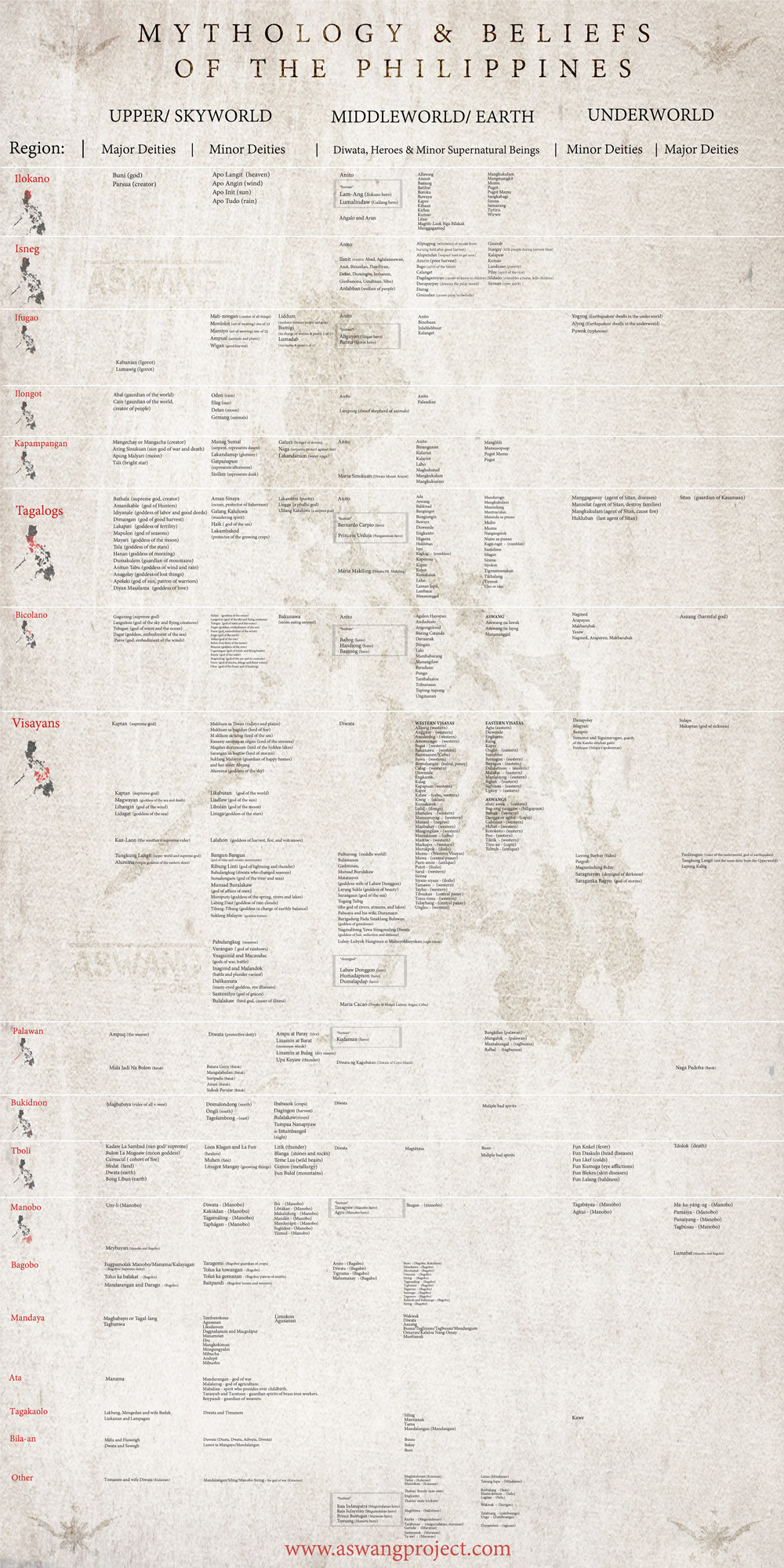

Dr. Ramos’ assignment of “lower mythology” in contrast to “higher mythology” unintentionally created an inferior classification. The research for the creatures of Philippine Mythology should be done within the framework of the Deities, because they are part of the same beliefs. In fact, I would argue that if you trace migrations to the Philippines and the early animist beliefs that were brought, they are older than the gods. Belief in gods and supreme beings came after belief in forest spirits and ancestral worship. Even the ancient Greeks believed in Pan, the half-man, half-goat nature spirit, before the Olympians came into the picture.

“Fractioning religion into two tiers – an overarching literary tradition associated with an elite versus local traditions associated with the folk – may mislead us in understanding religion among villagers and other non-elite populations.” -Benson Saler (Professor Emeritus of Anthropology)

Further compounding the confusion is the ridiculous notion that the Spanish invented these beings to keep native Filipinos afraid. The Spanish successfully destroyed the belief in gods, but they did not destroy the deeply inherent belief in folkloric spirits, and they certainly did not invent them. To the contrary, the Spanish found it a point of great frustration that the “natives” retained belief in their “superstitions” regardless of the efforts made by the friars.

The superstitions and omens of these Filipinos are so many, and so different are those which yet prevail in many of them, especially in the districts more remote from intercourse with the religious, that it would take a great space to mention them.

Spanish Document of 1691

The Spanish were, however, successful in changing the thinking about these beings. Before their arrival, it was generally understood that these ghouls and malevolent spirits were just doing what they were supposed to be doing. There was a great fear of them, but they were not considered “evil”. The Spanish concept of the devil swayed that thinking in the more populated regions. The Spanish also popularized the ideas of the western “witch”. Some may consider this “demonization” as a smoking gun, but I’ll remind you that surrounding countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Japan have equally grotesque and malevolent folk beings – all without the help of Spanish Friars. Still, the subconscious separation of lower mythological creatures from the deities persists in the Philippines

As stated above, creatures of lower mythology consist of beings that have no objective reality yet are regarded in folk traditions to actually exist. As each “lower” tier of mythology was discovered in the Philippines, it was viewed by the academe of the 20th century as a degradation of the original belief. They incorrectly equated “lower mythology” with “lower culture”. These animist beliefs and mythologies are imperfectly understood, but they predate monotheism and polytheism. As an outsider studying these things, I am thankful that the oral traditions of ancient Filipinos have kept them around. Any loss of cultural tradition should be seen as nothing less than tragic.

One would be hard pressed to find people who still believe in the ancient gods of the Philippines, but the creatures of Philippine lower mythology still hold a firm grasp. Both are integral to understanding early Philippine society. Unfortunately, the negative context of lower mythology and catechistic interpretations has made the subject almost taboo. This mentality has stunted studies in Philippine lower mythology since the mid 70’s. Filipinos seem to be stuck in this constant recycling of previous studies, and remain terrified to give these creatures the cultural importance they deserve. As this gap in time widens, the window into the ancestral past of the Philippines closes.

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.