When it comes to understanding Philippine Mythology, Folklore and Legends, the decolonization movement is a tricky one. It generally leans to one side – contempt for Western influence. There should be anger for all of the cultural traditions and identities that have been lost, but it should not overshadow what remains. This article is an attempt to have people consider blurring the divide some have created in Philippine beliefs (pre-colonial | post-colonial) and to understand how Filipinos synthesized religion. The Spanish period is well documented and can be used to understand the process in which earlier influences were incorporated into existing belief structures.

The decolonization movement and the recent interest in Philippine Myth & Folklore from Filipino-American youth embrace the image of the Spanish violently replacing existing belief systems through slaughter and fire. In many cases, the persuasive powers and tactics of the missionaries were so overwhelming that Filipinos had no choice but to toss their beliefs aside and embrace Catholicism. In 1595 just outside Manila, Fray Diego del Villar reported that many men and women were still seeking the guidance of the catalonan (priest or priestess in Tagalog pre-colonial religion). This caused a massive burning of all the idols in the village in front of the people residing there. The Spanish flogged and tortured the catalonans into submission.

Without a doubt, violent tactics were used but there was a much more dubious plot put into action that involved power and greed. For every Lapulapu, there is a Rajah Humabon. For every documented revolt against the Spanish, there are dozens of indifferent Filipino communities. One could argue that this was only through fear, but we also can’t ignore the lucrative deals made with the existing nobility and the parallels Philippine polytheistic beliefs shared with Christianity. Upon the Christianization in most parts of the Philippines, the Datus retained their right to govern their territory under the Spanish Empire. King Philip II of Spain, in a law signed June 11, 1594, commanded the Spanish colonial officials in the archipelago that these native royalties and nobilities be given the same respect, and privileges that they had enjoyed before their conversion. Their domains became self-ruled tributary barangays of the Spanish Empire. The Filipino royals and nobles formed part of the exclusive, and elite ruling class, called the Principalía (Noble Class) of the Philippines. The Principalía was the class that constituted a birthright aristocracy with claims to respect, obedience, and support from those of subordinate status.

With the recognition of the Spanish monarchs came the privilege of being addressed as Don or Doña – a mark of esteem and distinction in Europe reserved for a person of noble or royal status during the colonial period. Other honors and high regard were also accorded to the Christianized Datus by the Spanish Empire. For example, the Gobernadorcillos (elected leader of the Cabezas de Barangay or the Christianized Datus) and Filipino officials of justice received the greatest consideration from the Spanish Crown officials. The colonial officials were under obligation to show them the honor corresponding to their respective duties. They were allowed to sit in the houses of the Spanish Provincial Governors, and in any other places. They were not left to remain standing. It was not permitted for Spanish Parish Priests to treat these Filipino nobles with less consideration.

Once the Spanish colonial government had been established, the Spanish continued to recognize the descendants of pre-colonial datus as nobles, assigning them positions such as Cabeza de Barangay. This made implementing Spanish policy (and religion) much easier. It quickly became advantageous for these powerful families to keep order and maintain the status quo.

While the deities were replaced with God and other various patron saints, the folkloric creatures, spirits and superstitions persisted – to the extreme frustration of the Spanish. In a 1691 document it was mentioned, “The superstitions and omens of these Filipinos are so many, and so different are those which yet prevail in many of them, especially in the districts more remote from intercourse with the religious, that it would take a great space to mention them.”

There was simply no replacing these beliefs with anything from the Catholic faith. It creates an argument that early Filipino religion was not destroyed, as much as it was absorbed.

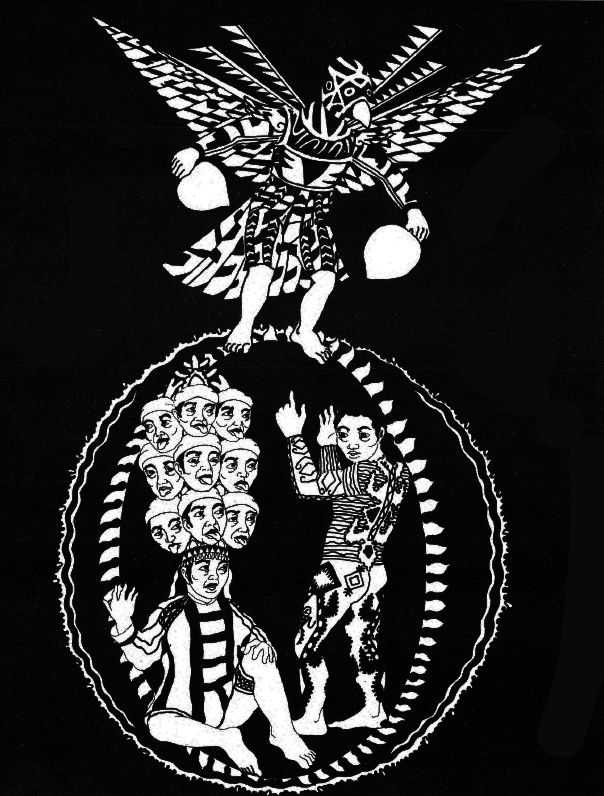

Folk Catholicism

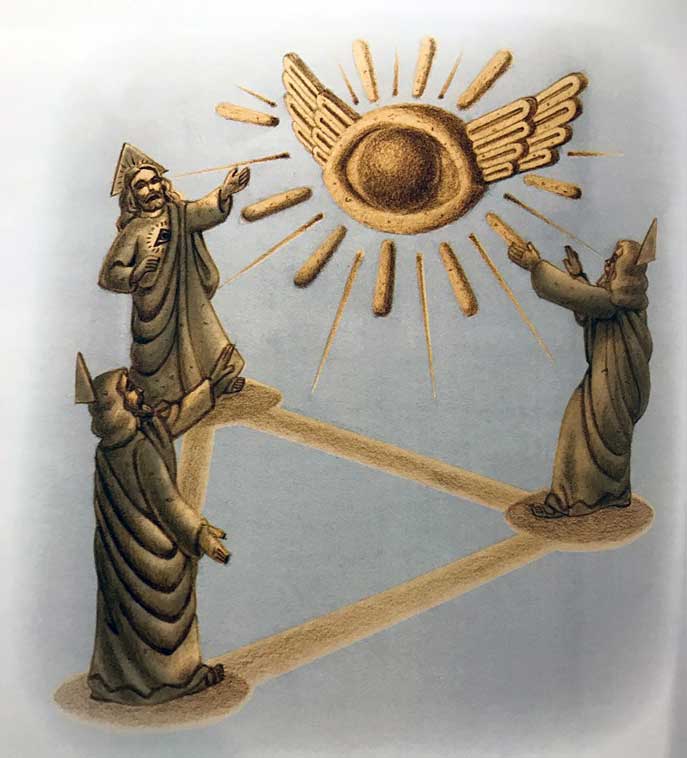

Records made by Spanish settlers and missionaries, and existing tribal religion, show that many indigenous Filipinos believed in a supreme sky god, or creator god. This god was invisible, his name was sacred and only spoken during rituals, and no known images of him were made. He was believed to be so far from humanity that contact was often made via ‘lower’ spirits, in the form of prayers and rituals. In some cases, there was also belief in a kind of ‘trinity’ of gods. Beneath the sky-god was his son, who was usually associated with the sun. There was also another god who was a kind of inherent spirit. Ideas from Hinduism entered Mindanao and Sulu, for trade took place between those two places and the Indian empires. Thus the Bukidnon creation myth has three divine persons. Dadanhayan ha Sugay has ten heads all drooling saliva; this looks like an extravagant version of the four heads of Brahma. Diwata na Magbabaya who looks like a human being (one head, two arms, two legs) may be a version of Siva who is so depicted. Agtayabun seems to be a composite of Siva and Vishnu. He has the Garuda’s hawk-like head and also the dancing motions of Siva, Lord of the Cosmic Dance. The parallels came from Hinduism and other Pacific religions, but early Filipinos were eventually convinced – by various means – that Catholicism was a superior belief structure.

In most parts of the world, animism blends in with formal religions. Among followers of the major religions lie many animistic beliefs and practices. Animistic beliefs actually dominate the world. Most Taiwanese believe in the Chinese folk religions. Most Hindus and Muslims in Central and Southeast Asia, and most Buddhists in China and Japan combine their religion with various animistic beliefs and practices. In many parts of the world, Christianity has not displaced the local folk religion but coexists beside it in an uneasy tension.

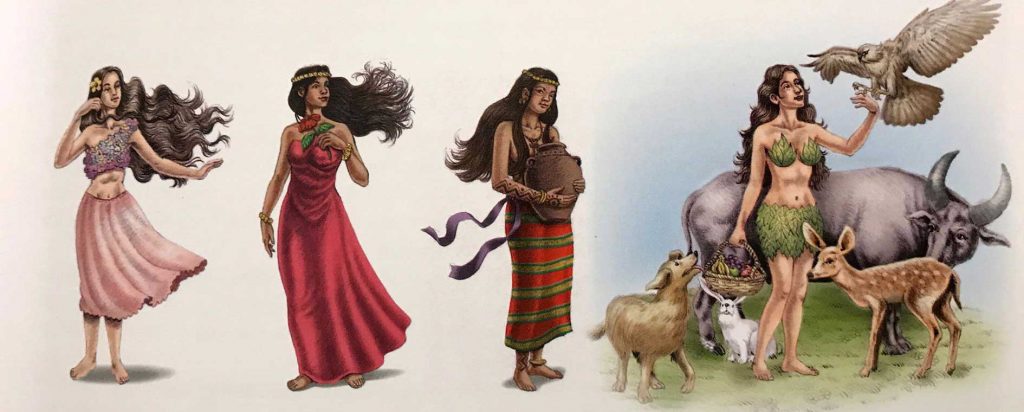

Since there are over 7000 islands in the Philippines there was a great diversity of animistic belief and practice, just as there are many ethnic groups and languages. The successive waves of immigrants that introduced Hinduism and Islam created a process of cultural adaptation and synthesis that is still evolving. As an example, Diwata (derived from Sanskrit devata देवता) replaced whatever names for deities and spirits were in place before Hinduism was introduced. Asuras (Sanskrit: असुर) introduced the concepts of asuangs. This synthesis continued when Spain introduced Christianity to the Philippines.

Filipinos stand out for their devotional fervor. Filipino Catholic practice is unusually material and physical, even among Catholic cultures, built especially on devotions to Mary, the suffering Christ, and the Santo Niño (Holy Child), and on powerful celebratory and penitential rituals practiced and experienced in a wide variety of Filipino vernacular forms. Feasts like the Black Nazarene, which draws millions to the streets of Manila in January, the Simbang Gabi novena that precedes Christmas, and the month-long Flores de Mayo offering to Mary illustrate distinctively Filipino forms of devotion.

Locals have special customs for almost every Sacrament and stage of life:

- Parents seeking Baptism of a child go in and out of the church before the child so that the young one grows up to be intelligent. The child is pinched so it cries during Baptism. Local people believe that if the mother does not dance before the image of Santo Niño (Holy Child), her child will get sick.

- Brides who try on their wedding dresses before the ceremony can expect bad luck. At the wedding feast a married couple comb their hair, stir water with the comb and then drink it.

- The members of a dead person´s family must pass under the coffin to stop the “chain of death” in the family. The body must always be taken out of the door feet first.

- Traditional cures are mixed up with religious Latin phrases. The Sacrament of the Sick is looked upon as a ritual which will deliver one from the sickness-giving evil spirit rather than as reconciliation or closeness to God.

- Anting-anting are not a Catholic practice, yet are tolerated being sold right outside the Quiapo Church in Manila.

Many Myths and Legends in the Philippines have a Catholic, or to be more exact, a Judaeo-Christian coloring, and sound very much like accounts in Genesis. But this is the point where we must not let our own particular modern, western and Christian sensibilities distract us from seeing them in their full reality.

The belief of the precolonial Filipinos in monotheism is manifested by another modern myth narrative in which the Bathala/ Infinito Dios was the one and only God. But the myth also had to take into account the arrival of the Santisima Trinidad (God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit) without antagonizing the natives’ monotheistic beliefs. Presumably the precolonial natives could not endanger Bathala’s monotheistic reign, and they could not just ignore the invading presence of the newcomer Santisima Trinidad.

In the Ifugao story of the first man and woman, it is impossible not to see the similarities to that of Adam & Eve. It is possible, of course, that this is a biblical story which was brought in by some wandering Christians several generations past; but the story evolved into something uniquely native. As the American anthropologist, H. Otley Beyer pointed out regarding the flood myths of the Philippines, “I see no good reason why the story should not also be [seen as] a native development in spite of its similarity to the Hebrew myth.”

Likewise, the Ilocano legend of “Lam-ang”, while apparently pre-Hispanic in its framework, makes reference to various introduced features such as tobacco, Christian names like Juan, Marcos, Pasyo and Ines, and a church wedding with a nuptial mass followed by feasting where the Fandango is danced.

What’s interesting to me, is that Hindu, Chinese and even Islamic elements are readily accepted into our understanding of indigenous beliefs, while many try to strip away Catholic influences. It may have to do with the Philippine education system essentially ignoring Philippine pre-history, but is also due to the decolonization movement. This, of course, is the goal of decolonizing, but it is also taking away the ability to learn through documentation how Filipinos evolved and incorporated foreign influence.

As E. Arsenio Manuel said, “Where History ends, Anthropology begins.” Nowhere is this more true than in the Philippines. If text books introduced to young students more than a few paragraphs outlining the theories surrounding the 4000 years of migrations and the inhabitants of the archipelago who even pre-date that, I believe there could be a better understanding to build a stronger cultural identity. There would also be a more solid footing to understand the importance of folk beliefs absorbed into Catholicism and to assist in illustrating the pre-colonial identity, rather than inadvertently rejecting aspects of it.

An Exercise Using Religious Legends

Legends form one of the important genres of folklore. They constitute, together with myths and folktales, the great group of folk narratives in prose. A good working definition of legend is that given by Stith Thompson. Equivalent to the German term Sage, this form of tale purports to be:

“an account of an extraordinary happening believed to have actually occurred.

It may recount a legend of something which happened in ancient times at a particular place—a legend which has attached itself to that locality, but which will probably also be toid with equal conviction of many other places … It may tell of an encounter with marvelous creatures which the folk still believe in— fairies, ghosts, water spirits, the devil, and the like. … It will be observed that they [legends) are nearly always simple in structure, usually containing but a single narrative motif.”

The attraction which legends have for the folk lay in the fact that what a legend narrates is considered as true by the narrator and the listener. Thus, the legend gives not only a formal artistic report of truth; it is, for the narrating folk, nothing less than a report of some real occurrence.

Forming a large and important group of Philippine legends are those that narrate the miraculous manifestations of God and His saints.

THE EXERCISE:

Using the descriptions below, replace any reference to Catholic figures with “diwata”, “anito” or “deity”. Change “patron” or “lady of” with “deity or anito of”. Similarly, imagine the images being described as an “anito” statue or likeness. This is largely what is speculated to have happened. In fact, it is still happening today. Many Manobo tribes use Catholic saints in their rituals, but change the names back to the indigenous deity (some of whom the name is only known to them) when any government or religious representative is visiting. This is a tradition that apparently dates back to the earliest Jesuit missionaries.

Some of the legends were undoubtedly created after the introduction of Catholicism, but through comparative analysis, others resemble existing myths that were not.

THE LEGENDS:

Around the Holy Infant (Santo Nino), a large body of legends has grown, especially about the Sto. Nino of Cebu. There are two Sto. Ninos: the image originally given to the wife of Humabon by Magellan and another, a black one, which a poor fisherman caught in three successive casts of his net, which is the subject of numerous legends. According to legend, it was just a piece of scorched firewood at first, but one morning it took the form of the Holy Infant. Many miracles are attributed to the Sto. Nino of Cebu, among them, delivering a ship during a storm; protecting men in battle; and rendering a devotee invisible so that he may not be sent to a disastrous battle. Being a child, the Sto. Nino can also be naughty, playing pranks on people. He would buy fish early in the morning from a peddler, telling him to come for the payment later; he would go out walking and come home with robes wet and amor seco sticking at the hem; he even volunteered to enlist in the army in 1942!

Similar miracles have been reported from other provinces where the devotion to Him is alive. From Bohol comes a legend saying that the Sto. Nino kept a poor old woman provided with food. The Sto. Nino of Leyte and Negros Occidental protected the townspeople from More pirates. One legend from Oriental Mindoro says that the Sto. Nino became the patron saint of Calapan after His image was found among kalap trees and miraculously manifested His desire to stay in that town.

The Crucified Jesus has also worked miracles which have been recorded in legends. The legend of the Holy Cross in Bauan, Batangas, is perhaps the best known of them. It tells how a crudely made cross standing in a rice field yielded water for the benefit of a maltreated wife who had been sent to fetch water from a distant source, on a cold and dark night, by a cruel husband. Another heartwarming story tells how the Crucified Christ detached his right hand from the Cross to give a loaf of bread to a hungry child who, in his innocence, had asked “the bearded man” (Bungot) on the cross for something to eat. This incident started a friendship between the child and Jesus, who took the child on a visit to heaven and to hell, and which in turn led to the conversion from sin of the people in the community.

-1.jpg)

The largest group of saints’ legends narrate the miracles performed by the Blessed Virgin in her various manifestations. There are numerous miraculous images of the Virgin Mary throughout the archipelago and many legends have been told about each of them. Some of the better known miracles are given below. The Virgin of Antipolo disappeared from her altar two times and each time she was recovered from the branches of a tipulo tree, from which the name “Antipolo” was derived. Her presence during the fighting against the Dutch brought victory to the Spaniards.

Our Lady of the Rosary of “La Naval” miraculously kept a sinful shipwrecked devotee alive for thirteen days in his mangled and rotting condition in order to give him a chance to confess his sins and receive absolution before he died.

The Nuestra Senora de Salambao allowed her image to be caught in the net by fishermen from Malabon but miraculously manifested her desire to be enshrined, not in Malabon, but in Obando, where she works miracles jointly with the two other patron saints of that town Santa Clara and San Pascual Baylon.

Our Blessed Lady of Caysasay of Taal, Batangas, performed perhaps the most dramatic miracle of all when she recalled to life a Chinese devotee, Hay Bing, who had been beheaded in compliance with a cruel decree. Noteworthy is the fact that this is the only legend, to my knowledge, in which a saint resuscitates a dead person.

The Virgin of Biglang Awa (“Prompt Help” or “Instant Mercy”), true to her name, quickly responded to the prayers for help of her people during a Moro raid. She appeared on the gate of the town carrying a reed with which she killed many of the enemy and unnerved the rest, who ran away.

A legend contains the folk version of the origin of the image of the Virgin of Penafrancia: she was found by a woman swinging in a hammock which was tied to the stalk of two pina plants in a pineapple plantation; hence, her name there is Virgin of Pina Francia. It is interesting to compare this version with the historical account.

Our Lady of the Rosary of Manaoag, Pangasinan, called by her people “the patroness of the sick, protectress of the helpless, and benefactress of the needy,” has performed many miracles for them: extermination of disastrous locusts, sending rain during the drought of 1706, protecting the church from fire, etc.. That she continues to perform miracles for modern-day believers is shown in the help she extended to two couples wishing for a child.

Our Lady of the Visitation of Piat, Cagayan province, has also endeared herself to the people of Piat by granting them numerous favors; e.g., sending rain during the terrible drought of 1624, the miraculous cure of an army officer whom doctors had pronounced hopeless, protection from shipwreck during a stormy voyage, etc.

About Our Lady of Dinagat (Surigao), an interesting legend is told. A rich and devout matron of Surigao lent a necklace to an unknown young girl, to use in a dance on the occasion of the feast of the Immaculate Conception. She later saw the necklace on the neck of the Blessed Virgin on the altar.

Our Lady of the Pillar of Zamboanga awakened a Spanish sentry to warn him of the coming of the Moro marauders. She also protected the people from tidal waves and floods resulting from earthquakes. She was reportedly seen, “a beautiful lady in white,” standing on the beach and motioning to the waves to be calm.

Another group of saints’ legends narrate the miracles performed by patron saints other than Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is perhaps indicative of the closeness which Filipino folk feel towards their patron saints that in some of these legends the saints are portrayed as participating actively in the everyday affairs of the folk. San Isidro, for instance, can joke and play with a little boy, asking him to collect cicadas for him and promising to pay for them. The little boy was found by his mother under the carroza of San Isidro waiting for “that boy” (San Isidro) to pay what he owes him.

San Bartolome is shown as participating in the customary bathing of religious images (nagsasalibanda) during the town fiesta in Lumban, Laguna, and inviting people to look him up in Nagcarlan (where he is patron saint). One man who did so found him on the altar at Nagcarlan.

San Diego, during his wanderings in Batangas, asks for a drink of water at the home of a crippled girl and cures her in the process.

Most amusing to me is the legend in which the patron saint herself, Sta. Ines, orders some nipa and bamboos delivered in front of her chapel, which had collapsed but had not been repaired by the people.

One thing that stands out in all these saints’ legends is the strong faith of the folk in God and his saints. They firmly believe that “saints will aid if men will call, for the blue sky bends over all,” as Coleridge once said.

One other category of religious legends may be identified, in addition to the miracle stories attributed to particular saints. These are the legends about the punishment of great sin. One group of these explain the origin of particular lakes, in which extreme worldliness, selfishness, pride and snobbishness are punished by causing a whole town or homelot to sink and become a lake (see origin of Sampaloc Lake and Paoay Lake in Myths). For the same sins, all the inhabitants of a town, except a good and pious couple were afflicted with smallpox, according to a Negros Occidental legend. In a legend explaining the origin of the burnt rice grains to be seen on the beach of Puerto Galera, the punishment for extreme selfishness and covetousness was for all the rice of the owner to be burned and strewn on the beach.

Conclusion:

The old religion continues to thrive today though in various forms, for instance, in what is commonly called “superstition.” When people make sense of the world around, they may turn to the dominant beliefs of their milieu, be these secular or religious. Or they may turn to other beliefs which may be fragments of an earlier religion. Such fragments are derided as “superstitions,” although one can argue that any interpretation, religious or secular, that does not square with reality, is also a superstition. The old belief in numerous, vulnerable spirits surfaces when rural Christian Filipinos warn their children about wandering about at dusk or throwing water carelessly; they might bump or wet a passing spirit. Sleeping close to a wooden post is considered dangerous, for nature spirits may continue to dwell within. Food offerings are still being made to ancestral spirits in many places throughout the Philippines.

Sometimes it takes a foreign fad to stir up dormant belief. Much-travelled Filipinos, who regard themselves as the acme of sophistication, have discovered that quartz stones can heal affliction. They have picked up the belief from trips to the West Coast where shops specialize in the occult. But, there is a native basis for this belief. People in the provinces value quartz stones as powerful objects, being “splinters of the sun.”

Some organized cults among Christian Filipinos continue the old religion. The most eminent example are those of Mount Banahaw in Quezon. The many churches on the fabled mountain have Christian names and celebrate elaborate versions of the Catholic mass. But their theology centers around a pilgrimage from the base of the mountain to the crater of the peak. Along the way are stations, called pwesto, where Hail Marys are recited. The pwesto are really natural formations: boulders, waterfalls, pools of water, caves. It is believed that, after death, the soul journeys up the mountain following the pilgrimage path. It is better therefore to make the pilgrimage now, as a rehearsal, than after death when the soul might lose its way. Significantly enough, the crater is the final destination. For Filipino ancestors, craters and caves were entrances to the underworld.

PHOTO CREDIT: Dennis Santos Villegas

As a outsider looking in, understanding the ways Filipinos synthesized different religions could help with a self-definition as a people. You may not agree with those ways, but should carefully examine them, for they are alive in the minds and hearts of the majority, indeed even in those who glory in being educated and modern. In a world where pluralism has become the norm, one should never view beliefs with an exclusionary light.

While the old idols disappeared, the seers and healers of the old religion survived. Convened to the new faiths, they continued to practice the ancient ways in secret. They were vilified for being “in commerce with the devil,” but villagers sought them out because of their tested powers. And indeed they earned a tremendous amount of knowledge in their heads. They knew a wide variety of plants and animals and their healing purposes. They knew the myths, epics and tales which summed up the experience of their ancestors and provided a guide for everyday life. They presided over rituals that comforted their fellow members at crucial junctures in life. Such lore was, and still is, transmitted orally. And to fully understand it, we need to look at the synthesis of Christianity.

SOURCES:

Myth and Symbols Philippines by Fr. F.R Demetrio S.J (Revised Edition)

You Shall Be As Gods: Anting-Anting and the Filipino Quest For Mystical Power, Dennis Santos Villegas, Vibal Foundation, Inc. 2017

Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society, William Henry Scott, Ateneo Press (1994)

THE SOUL BOOK, Demetrio, Coredero-Fernando, Zialcita, GCF Books 1990

Philippine Folk Literature: The Myths, Damina Eugenio UP Press (2001)

Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends, Damina Eugenio, UP Press (2001)

Animism in Malaysia and other religions by Raenne Man

filipino catholicism has traits of prechristian folk religion – ucanews.com

Motif-index of folk-literature : a classification of narrative elements…Stith Thompson, Indiana University Press, 1955-1958

ALSO READ: The Hidden Myth Behind the Symbolism of the Anting-Anting

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.