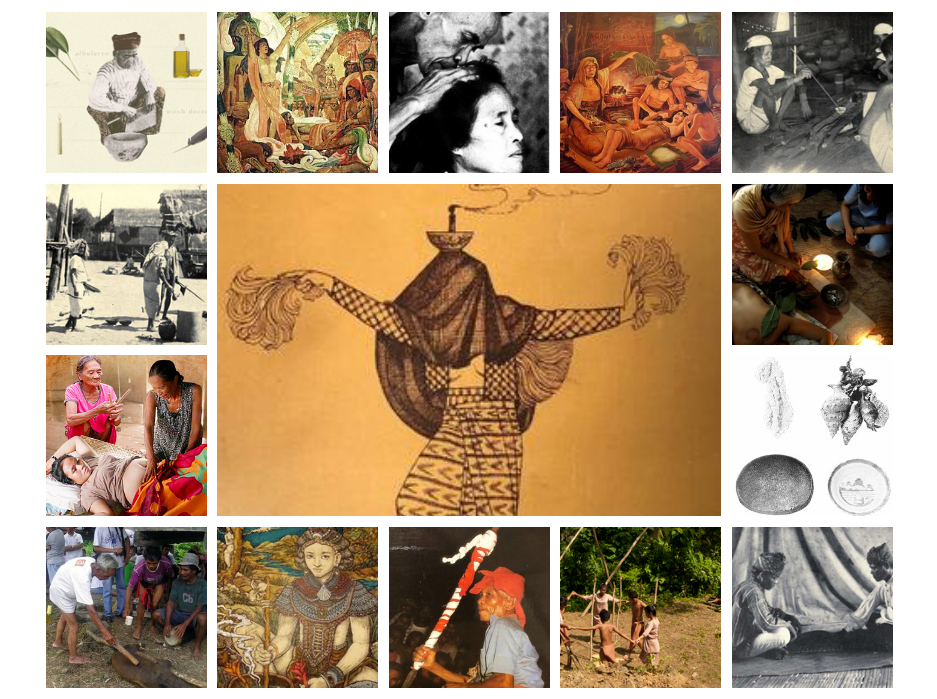

In recent years, the term babaylan has dominated the conversations regarding historical and modern indigenous religious narratives. There is good reason for this. From the closing decades of the 16th century up to the early 1900s, Panay Island in the Western Visayas had its historical timeline dotted with uprisings led by the babaylanes against the missionaries. Friars assigned in different parts of the island were poisoned or speared to death (see: Tapar Revolt). Fray Juan Fernandez in his annotations (Monografia de los Pueblos de la Isla de Panay, 1899) identified the interior towns like Lambunao and Tubungan in Iloilo and Antique province as the stronghold of babaylanes. This area of the Visayas also saw the babaylan evolve from a female position, to gender nonconformity, and ultimately becoming a predominantly male role. The available historical documentation has been used in comparison, and to contrast, modern social meanings, making the babaylan a powerful symbol and a fashionable term.

Enthusiasm towards presenting the bygone aspects of the babaylan practice are often applied to the entire Philippines with such vigor, that the surviving animist beliefs and folk healing among the various ethnolinguistic groups are pushed to the fringes of conversation. I decided to compile an introduction to the many names of Philippine shamans and healers – both historical and practicing. As far as I know, the only names on the list that could be considered a ‘defunct’ practice are that of the Katalonan, Asog, and Bayoc/ Bayoguin.

This is by no means a comprehensive list, and I plan to continue adding to it. It should be strongly noted that these beliefs can vary greatly, even among the same ethnolinguistic group. Further, these beliefs continue to evolve and may not be exactly the same as when the documentation was published.

Please feel free to send suggestions or corrections to me.

TAGALOGS:

Katalonan

The Spanish documented the Katalonon as the men and women shamans of the old religion. They were responsible for healing the sick, rendering prayers, offering ceremonies to idols, and making treatments and cures.

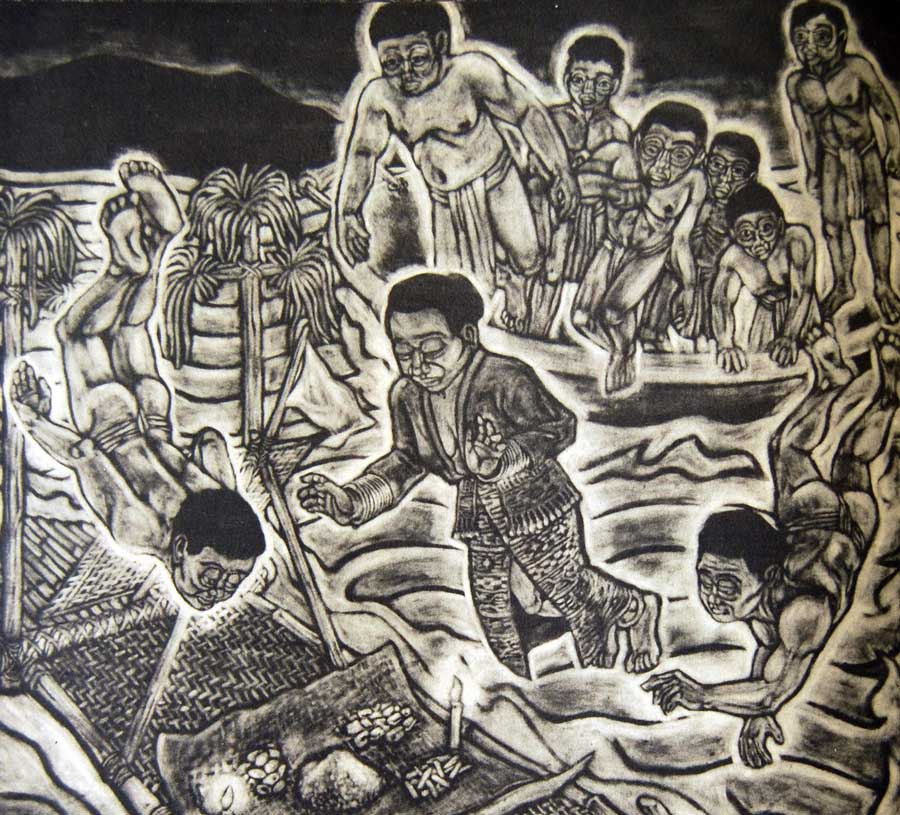

“They summoned a catalonan, which is the same as the vaylan among the Pintados, that is, a priest. He offered the sacrifice, requesting from the anito whatever the people desired him to ask, and heaping up great quantities of rice, meat, and fish. His invocations lasted until the demon entered his body, when the catalonan fell into a swoon, foaming at the mouth. The Indians sang, drank, and feasted until the catalonan came to himself, and told them the answer that the anito had given to him. If the sacrifice was on behalf of a sick person, they offered many golden chains and ornaments, saying that they were paying a ransom for the sick person’s health. This invocation of the anito continued as long as the sickness lasted.”[1]

Bayog or Bayoguin

Regarding sacrificing of animals, the Spanish noted, “All of this is administered by a priest dressed in female garb. They call him bayog or bayoguin; another woman for the same office they call catalonan.”

Although these Indians have no temples, they have priests and priestesses who are the principal persons of their ceremonies, rites and omens, and to whom all the important affairs are entrusted, paying them well for their labor. Ordinarily they dress as women, act like prudes and are so effeminate that one who does not know them would believe they are women. Almost all are important for the reproductive act, and thus they marry other males and sleep with them as man and wife and have carnal knowledge. These are called bayog or bayoguin.[2]

Bayoguin, signified a “cotquean,” a man whose nature inclined toward that of a woman.[3]

Albularyo and Mangluluop

The albularyo are general practitioners of folk medicine. They are not specialists in the sense of limiting their work to one aspect of healing, although their forte is the use of medicinal plants. Most of them also know how to diagnose, take the pulse, and perform the curing ritual if there is no specialist on hand to do it. For example, if an albularyo suspects that an illness is due to lamang-lupa (dwellers of the earth), he calls for the mangluluop to perform the ritual. This is not because he does not know how to do the ritual himself but because of the belief that the mangluluop has greater power than anybody else in controlling the disease as well as in influencing the environmental spirits to follow his bidding. The mangluluop is the ritual specialist, a diviner. As soon as he discovers the source that has caused the illness of the patient, he lets the albularyo take over the case.[4]

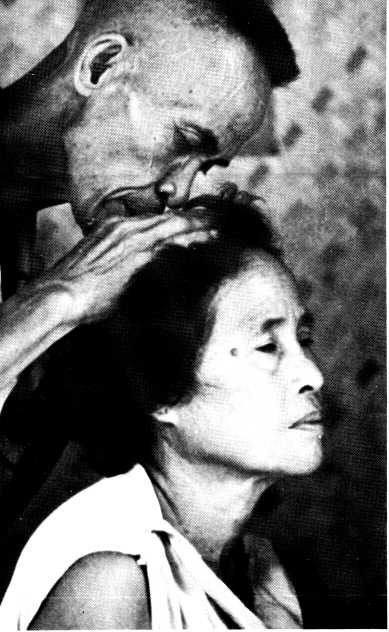

Manghihilot

The manghihilot are specialists in fractured or broken bones, sprains, and other sala (a generic term for all kinds of discomforts having to do with muscles and bones). Each manghihilot has his own system of locating a sala. There are those who use a special kind of mirror (salamin), smudged at the back with an orange-red color, known as dalandan.

The second group of manghihilot is made up of those who use fresh banana leaves, especially from a species known as saba. A frond, three inches wide, is secured and wilted over the fire. Next, this is drenched with oil. Medicinal prayers are whispered over it. Then it is placed on the breast of the patient. The same process is done at the back.[5]

Magpapaanak

Midwives are better known as hilot. Most of F. Landa Jocano’s informants, however, use the term magpapaanak in referring to midwives, in order to distinguish them from the masseurs who are also known as hilot or manghihilot. The term hilot is derived from the activity used in the healing process. The magpapaanak orhilot are men or women who are skilled in assisting mothers in the delivery of their babies.[6]

Magluluop

The magluluop are specialists in divining illness through a ritual, known as luop. Some magluluop may also be albularyo, but most of them are simply diviners of illness, particularly those caused by the environmental spirits. If the magluluop is merely a diviner, he does not treat any disease unless it is absolutely necessary, as in emergency cases; instead, he refers the illness he has diagnosed to the appropriate specialist who has the power to cure it.[7]

BIKOL

Balyanas

When calamities befell ancient Bikolanos such as locusts, epidemics, or typhoons and believing Aswang to be the author of all the miseries, they would endeavor to destroy its spell by performing a ritual called hidhid. This was also performed on sick people who were suspected to be suffering through the malice of Aswang. In the hidhid the balyana puts some buyo leaves and rice grains above the head of the sick. The balyana would go around the person several times, dancing and performing various contortions as well as mumbling secret phrases to exorcise the Aswang. If the sick person was cured they would say it was because of the efficiency of the balyana and if this ended in death they would conclude that the [sick was] taken by Aswang to gagamban to suffer horrible events.[8]

Asog

The people of Bicol would hold a thanksgiving ritual called atang that was “presided” by an “effeminate” priest called an asog. His female counterpart, called a baliana, assisted him and led the women in singing what was called the soraki, in honor of Gugurang (supreme deity).[9]

Parabulong

The paulaw ritual is carried out in order to supplicate the spirit world, particularly the engraft or the aghoy, who inhabits the place where a house is to be built, to protect the workers from harm and to accept the disturbance that may ensue on account of the construction work on the premises. The paulaw is administrated by a parabulong or faith healer who is accustomed to such activities being a friend or nemeses of the spirit world inhabitants. [10]

Parabawi

When a bad spirit enters the body of a person, this person gets sick. He suffers from high fever and assumes the personality of the spirit inside him. Hence, his voice, his words, and his knowledge about things may amaze the people around him. To bring this person back to his world, he needs a parabawi.[11]

Other names recorded for healers among the Bicolanos are paratatak (one who performs circumcision)

In Albay, the practitioner of santiguar is called a parasantiguar. Santiguar is a Spanish term meaning “to make the sign of the cross,” but its meaning in Latin America and the Philippines is “to heal.” According to an online informant (J. Lorico, Manila), the Parasantiguar is someone who uses fire or water to determine the cause of certain ailments. Usually these are the ones connected to supernatural reasons such as sickness due to an elemental, kulam, or barang. Most of the time they perform the ritual using melted wax poured on a basin of water or a plate oiled with lana and then exposed to fire. The Parasantiguar interprets the images formed through this process and assesses what the patient needs to do to be healed.

The Bicolano healers that come closest to the Ma-Aram Panay model of healing are those known as the paraanitos, anito (ancestors/spirits), and paradiwata, diwata (deities), healers.[12]

VISAYAS

Babaylan (Central and Western Visayas)

Also known as dailan (from dait which means friendship/peace), the babaylan was mediator between the gods and the people and healer of the body and spirit. Mostly played by women, the babaylan’s role bordered on the political as well, being a close adviser of the datu in almost all matters concerning religion, medicine, natural phenomena, etc.[13]

The term Babaylan is most used on Panay, Negros and other areas of the Central and Western Visayas. The Hiligaynon “babayi” for woman shows a close relation to the term “babaylan”. In Kinaray-a, an ancient language still being spoken in Antique and some interior towns of Iloilo, “bayi” and “bay/an” are the terms used. In Kinaray-a, “bayi” is also used to refer to one’s female grand elders. “Babaylan” then implies an age-old tradition embodied in the concepts basic to the culture and society of Panay.[14]

Ma-Aram (Panay)

The ma-aram practice of Panay among the Karay-a is a phenomenon referred to as binabaylan by the nonpractitioners as well as those less sympathetic to the practice. In Barrio Mariit, where this phenomenon exists, practitioners prefer to be called ma-aram (literally means “knowledge”) due to the pejorative connotation attached to the term binabaylan by non-binabaylan believers. While this practice is the same role as the historical babaylan, in modern times it is mostly a male practitioner.[15]

SOURCE: The Enduring Ma-aram, Alicia Magos, New Day Publishers, 1992

Asog (Leyte and Samar?)

“The Asog considered themselves more like women than like men in their manner of living, or going about, or even in their occupations. Some of them applied themselves to women’s tasks, like weaving and cultivating, etc. In dress, although they did not wear petticoats (these were not worn by women in ancient times either) they did wear some Lambon, as they are called here. This is a kind of long skirt down to the feet, so that they were recognized even by their dress. Unlike female shamans, they neither needed to be chosen nor did they undergo initiation rites. However, not all asog trained to become shamans.”[16]

Mananambal (Cebu)

In Cebu, located in the Visayas region of the Philippines, a traditional albularyo is called a mananambal and their work of healing is called panambal. Like the general albularyo, mananambals obtain their status through ancestry, apprenticeship/observational practice, or through an epiphany and are generally performed by the elders of the community, regardless of gender. Their practice, or panambal, has a combination of elements from Christianity and sorcery. The combinations are a reflection of the legacies left from the conversion to Catholicism of the islands from Spanish colonization, since the Indigenous of Cebu had direct contact with the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, and on-going Indigenous practices before colonization. The panambals cover natural and supernatural illnesses using a wide range of methods. Two common methods used are herbal medicine and orasyon, healing prayers deriving from a bible equivalency called the librito.

Mananambals treat major and minor ailments. These ailments include but are not limited to: headache, fever, cold, toothache, dengue fever, wounds, Infection, cancer, intellectual impairment, and other illnesses thought to be caused by supernatural creatures.[17]

Diwatero, Mamumuhat (Bohol)

On Bohol, the diwatero and mamumuhat are the ones who cure illness specifically caused by supernatural beings and buyag. They are a medium who acts as intercessor between humans and the spirits.[18]

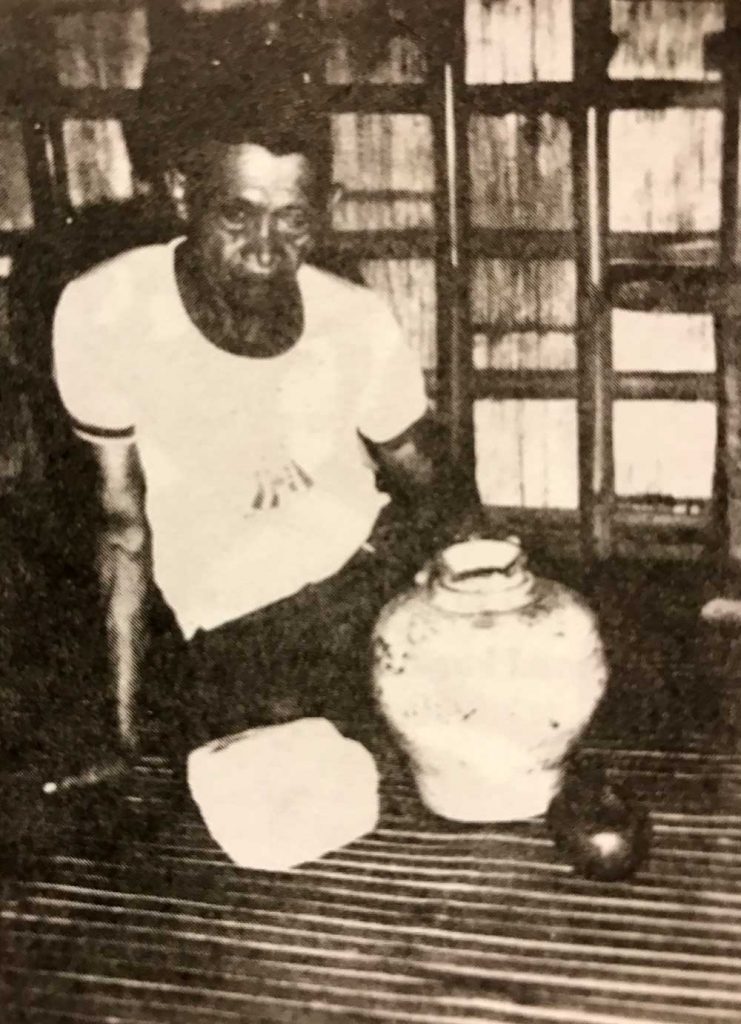

Tambalan (Leyte & Samar)

The tambalan (herb-doctor or medicine man) is, even in modern Philippine society, a respectable personality. In cities and towns with modern hospitals, the tambalan is still called by the upper-class Filipino in cases where modern medical practice seemingly fail. Among the lower-class people, particularly those found in barrios, the tambalan is more trusted than the district health inspector who regularly visits their places. The reasons for this attitude are manifold. In folk-belief, the tambalan is believed to have supernatural powers to contact and control the spirits. A sickness caused by spirits, which cannot be cured by modern medicine, can only be cured by the tambalan; therefore he has, in the mind of the ordinary people, an edge over the modern doctor. His personal approach, compared to the cool professional attitude which often characterizes that of the doctor or health inspector, in applying his remedies and the long rituals involved in their application have a quieting and favorable effect on the patient. The money question may be another reason for securing the services of the tambalan. Since it is believed that the healing power of the tambalan is a supernatural gift which might be lost if money is taken for his services, the medicine used by him is cheap and is often without charge. For a grave sickness, payment may be in kind, such as food and tuba which can be secured more easily than the cash that may be needed for an injection prescribed by a modern doctor. Thus for financial reason the poorer classes’ are compelled to avail themselves of his services, although to the well-to-do this cannot be true, because of their willingness to spend more money for a banquet that the tambalan may require than for the cost of the necessary medicine that may be prescribed by a modern doctor. [19]

Mang hihilot and Manug luy-a (Negros Occidental)

The Mang hihilot and Manug luy-a are considered traditional healers. People usually come to these healers if they experiencing illness. The Magnug luy-a had the power or ability to bestowed supernatural being which given by the Holy Spirit. Manugluy -a is very familiar with the rituals, and modalities of diagnose and healing, prayers, whisper (bulong) and orasyon, and the use of herbal medicinal plants. They are familiar with the different spirits causing illness, which are the dwarfs and nunos. (Research by JOY VINGNO, Ph.D. and MARISA G. VELARDE)

The Visayas, as well as other areas of the Philippines also have albularyo. The name was adapted during Spanish times from herbolaria (herbalist), and has likely replaced the names of traditional practitioners throughout the archipelago.

Other names for healers in the Visayas, including Samar, Leyte, Cebu, Bohol, and among the Bisaya speakers in Northern Mindanao are: baylan (also balyan, balian, baliana, vaylan), katooran (also catooran), makinaadmanon, anitera (or anitero), mananambal (healer), himagan (healer), siruhano (herbalist), manghuhula or manghihila (diviner), mananabang (midwife).

CORDILLERAS

Mambunong, Mansip-ok, Mankutom (IBALOY and KANKANA-EY )

This office is usually held by wise old men experienced in the life and ways of their people. The mambunong (lit., the maker of prayers) presides in all the feasts requiring the recitation of bunong or prayers. Any one can become a mambunong as long as he learned the correct procedures sufficiently well to approach the deities and spirits, for them to grant his intercessions or to effect a cure and good fortune. One learns the procedures and prayers associated with each ceremony through constant listening and observing, or through direct instruction of a mambunong. These priests are generally classified into two classes. One class, composed for most part of women, performs rituals reserved for special ceremonies; and the other, composed of older and experienced mambunong, performs familiar rituals. The latter are called manbahi and they usually preside in special feasts afforded only by the baknang.

The person who identifies the causes of illness is called mansip-ok who determines the reason for the sickness by using a pendulum-like instrument (a string and stone) that he holds close to his forehead while mentioning the probable causes of the sickness. When upon mention of a probable cause the string swings faster and farther away, this is an indication that the mentioned cause is the reason for the person’s illness.[20]

The mankutom (wise man), on the other hand, interprets the meaning of events. For example, when a kitchen utensil breaks during a marriage ceremony the mankutom may interpret this as a premonition for the breaking up of the couple. Certain ceremonies are then performed to remove its ill effect.[21]

Munagao and Mumbini (IFUGAO)

There are a great number of priests with varying proficiencies. As a rule, the priests are males, but there are a few women who may also lead in such rites as the illness rites (mumungao). Women priests are called mungao while male priests are called mumbini.

Oftentimes, a person becomes a priest through inheritance from their father priest, or through a near relative who teaches the rites during the instruction period, as well as during consecration of the new priest.[22]

In more modern times, an Ifugao Mumbaki is a kind of religious specialist who can perform various healing rituals as well as engage in spiritual practices. Originally, Mumbaki may have been a type of healer who treated illnesses caused by witchcraft. This is why they are occasionally called witch doctors. Nowadays, such shamans practice alternative medicine such as chiropractic, homeopathy, and also faith healing. They also engage in prayers to ensure abundant harvests.

Dorarakit (ISNEG)

The Isneg shaman or dorarakit (sometimes called anitowan, on account of her connection with the anito or spirits) is always a woman. The functions of a dorardkit are numerous and varied. She determines, chooses, collects and distributes the tanib or amulets, which play such an important role in the life of an Isneg, although not all of these come under the jurisdiction of a single shaman. She is the universally accepted physician and surgeon in all kinds of sickness

There are a few medicine men among the Isneg, but they never perform the maxanito and are not regarded as dorarakit. These medicine men are mostly herb doctors, although some of them occasionally extract the cause of sickness from a sick person’s body, in the same way as a shaman does. A few of these men are even credited with the power of fighting spirits, in proof of which they exhibit tresses of a spirit’s hair, walk upon the water, etc.

The position of shaman is not hereditary among the Isneg. To be considered a dorarakit, it is sufficient for a woman to have been consecrated by another shaman, but such a consecration is absolutely required. The choice of candidates depends entirety on the will or whim of the consecrating shaman, who is free to choose her own daughter or that of another woman, whether with or without the knowledge of the mother.[23]

Alopogan (TINGGUIAN)

The superior beings talk with mortals through the aid of the alopogan, known individually and collectively as alopogan (“she who covers her face”). These are generally women past middle life, though men are not barred from the profession, who, when chosen, are made aware of the fact by having trembling fits when they are not cold, by warnings in dreams, or by being informed by other alopogan that they are desired by the spirits. A woman may live the greater part of her life without any idea of becoming a alopogan , and then because of such a notification will undertake to qualify. She goes to one already versed, and from her learns the details of the various ceremonies, the gifts suitable for each spirit, and the chants or dīams which must be used at certain times.[24]

Mangalisig, Manganito, Mandadawak (KALINGA)

The priesthood is almost entirely in the hands of women. Entry into it is always in answer to a “call”, and is in a sense, compulsory: the woman begins to sleep badly, has many dreams, grows thin, lacks appetite, believes that her soul has married an anitu and that she can extricate herself from the condition only by becoming a priestess (mangaalisig). Or she may become conscious of the call from getting a stomach upset after she has eaten foods that are taboo to priestesses: eel, dog, certain fish, meat of the cow (but not carabao). She is said to be taught the rituals by the gods themselves, not by the older priestesses.

Men are much more rarely priests, but there are a few, and some of them have great renown. Priests formerly concerned themselves mainly with head-hunting rites, but, now that there is little or no use for these, there is little use for priests, except the few exceptional ones who undertake to cure sickness.[25]

The medium, healer or priestess also goes by the names manganito or mandadawak.

Mabaki (IKALHANS)

Among the Ikalhans, the mabaki takes care of all the ritual proceedings. It is he who invokes invitations to the ancestors and spirits (ampahit) to join the celebration and bring blessings.[26]

Insup-ok (BONTOK)

Every individual or household has the power and knowledge to intercede with the anito, although often times, the seer or medium (insup-ok) is called to heal afflictions caused by malevolent spirits. In every ceremony the spirits are invited to take part in the animal sacrifices through the kapya, a prayer composed extemporaneously by the presiding insup-ok.[27]

PALAWAN

Babaylan (TAGBANUA)

The Tagbanuwa babalyan have numerous duties and influence upon the everyday social activities of the people. They select ritually favourable clearings, placate environmental deities, interpret dreams, provide charms for hunting and fishing, and treat all types of serious illness. During the familial ‘bilang’ ceremonies any adult can invoke the spirits of the dead. But the many deities which appear during the ‘pagdiwata’ rituals can only be called by the babalyan. They guide the interaction of the living with the deities as well as with the dead.

The majority are women, but the higher religious functionaries are men in political and juridical roles. The position of babalyan is not inherited. There is, nevertheless, a marked tendency towards direct lineal succession.[28]

Babalian (BATAK, Tanabag)

In traditional Batak society shamanism is the prerogative of male specialists known as babalian. Shamans contact spirits during trance, predict future events and are said to possess the gift of clairvoyance. They administer therapeutic remedies and supervise collective subsistence practices, as well as ceremonies to re-establish the cosmological balance.

In this respect, their role as managers of natural resources is of great relevance. Certain wilds trees, such as the providers of pollen for the bees, the providers of resins and medicine, etc. as well as different animal species are believed to be under the control of mystical entities (panya’en). Such entities are also regarded by Batak as taw (persons), in the sense that they are said to possess a human consciousness and, thus, the ability to establish meaningful interaction with everyday people.[29]

Bäljan (Lowland PALAWAN People)

A male ritual specialist, bäljan, conducts rituals, but many other people both male and female, perform ritual dances with or without trance. Everywhere amongst lowland Palawan people, gong beating is synonymous of ritual calling of the deities, diwata, or “Powerful Ones,” kawasa. During cleansing rituals, the bäljan is responsible for what is happening, and he should be able to fight and drive away the galap or tandajag (giant serpent) before it swallows the whole country or makes it disappear in a hole or a lake where it would sink with all its denizens.[30]

MINDANAO

Maibalian (BAGOBO)

The mabalian are people—generally women past middle life—who, through sufficient knowledge of the spirits and their desires, are able to converse with them, and to make ceremonies and offerings which will attract their attention, secure their good will, or appease their wrath. They may have a crude knowledge of medicine plants, and, in some cases, act as exorcists.

The ceremonies which art performed at the critical periods of life are conducted by the mabalian, and they also direct the offerings associated with planting and harvesting. They are generally the ones who erect the little shrines seen along the trails or in the forests, and it is they who put offerings in the “spirit boxes” in the houses. [31]

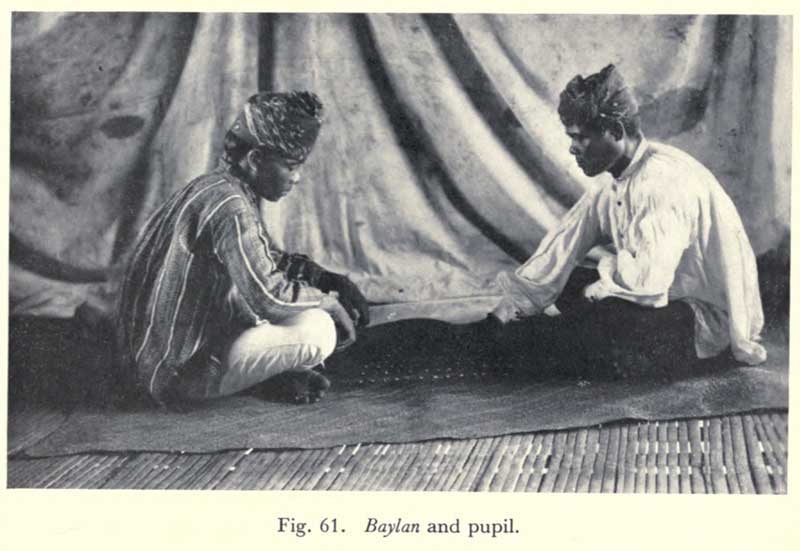

Baylan (BUKIDNON)

Most traffic with the spirit world is through or with the aid of the baylans —a group of men or women who claim the ability to discover the cause of sickness. They also know how to conduct ceremonies acceptable to the spirits. It is said that the first baylan was taught by Molin-olin, the spirit of his afterbirth brother, who for this reason is considered a patron and guide. Two other spirits, Ongli and Domalondon, also appear to the baylan and usually assist in determining the cause of the trouble. The baylans do not form a priesthood, although they are a definite group. Should one of them be visiting in a village where a ceremony is in progress he or she assists as a matter of course.[32]

Ballyan (MANDAYA)

There is in each community one or more persons, generally women, who are known as ballyan. These priestesses, or mediums, are versed in all the ceremonies and dances which the ancestors have found effectual in overcoming evil influences, and in retaining the favor of the spirits. They, better than all others, understand the omens, and often through them the higher beings make known their desires. So far as could be learned the ballyan is not at any time possessed, but when in a trance sees and converses with the most powerful spirits as well as with the shades of the departed.[33]

Bailan (MANOBO, Agusan)

The bailán is a man or woman who has become an object of special predilection to one or more of those supernatural friendly beings known among the Manóbos as diuáta. This will explain why the word diuatahán is frequently used, especially by the mountain people, instead of bailán. John Garvan was frequently told by priests that this special predilection of the deities for them is due to the fact that they happened to be born at the same time as their divine protectors. This belief, however, is not general.[34]

Onituwan (MANOBO, Mt. Apo)

For the Manobo people, the unseen world of spirits is as real, if not more so, than the seen or physical world. There are many spirits with Monama the Creator and onitu ‘spirits’, each of whom has been given authority to watch over an area of creation. Spirit mediums onituwon allow a spirit to possess them which then becomes their familiar spirit. Then there are a host of spirits, good and bad, residing in the rocks, hills, trees, caves, rivers, and all of nature.

These spirits would make friends with people whom they liked because they were good to them. A person who has a familiar spirit is called an onituwon ‘spirit medium’. The spirit tells what he needs through the person he enters. That per son then be comes like a prophet. There are many spirits who watch over this world.

If some one is sick, those they accuse are the evil spirits, because it is said they were inflicted by an evil spirit. There fore they gather medicinal plants in the wild for the one touched by an evil spirit. These beliefs concerning evil spirits are still prevalent today. And the beliefs are not gone be cause the Manobo people believe that they were also included at the creation of the world.[35]

Pantak, Pamonolong, Pendarpaan (MARANAW)

Maranaw society traditionally believes “illnesses are directly or indirectly caused by spirits that inhabit the world.” Magical-curative services are administered by a pantak (sorcerer) who injures a person’s enemy; gagamoten (magical poisoner) charms a loved one with kata-o sa kababago-i, equivalent to gayuma or lumay; pamonolong cures corporal sickness and poisoning of an individual through a tawar or a prayer or magical spell, and, pendarpaan (spirit medium) cures any type of sickness except those determined by fate. Diagnosis of the cause of illness is done first before traditional healers conduct treatment.

With respect to pre- and post-natal services, all birth needs of expectant women are attended to by pandai a babai or panggawai (midwife) who in turn assists the pandai a mama (male childbirth consultant) The pandai a babai regulates Maranaw women’s menstrual flow and cycle. It is usually attended by a pangingilot (another term for midwife) who uses hilot (massage).[36]

Kalamat (SAMA-BAJAU groups)

Traditional Sama-Bajau communities may have shamans (dukun) traditionally known as the kalamat. The kalamat are known in Muslim Sama-Bajau as the wali jinn (literally “custodian of jinn”) and may adhere to taboos concerning the treatment of the sea and other cultural aspects. The kalamat presides over Sama-Bajau community events along with mediums known as igal jinn.The kalamat and the igal jinn are said to be “spirit-bearers” and are believed to be hosts of familiar spirits. It is not, however, regarded as a spirit possession.

Religion can vary among the Sama-Bajau subgroups; from strict adherence to Sunni Islam, forms of folk Islam, to animistic beliefs in spirits and ancestor (umboh) worship.[37]

BATANES and BABUYAN ISLANDS

Machanyitu (IVATAN)

Folk herbal medicine has been developed together with the practice of machanyitu or calling for the assistance of the anyitus. His powers are generally regarded as beneficent to good people and threatening to the bad. He can catch thieves and discover the cause of illness and bring their cure by communicating with the invisibles. Healers also go by the names mamkāw , masulib du dasal or malatin , manulib , and mamālak . In so far as they deal with illnesses believed to be caused by invisibles. They are regarded as privileged humans who are not only of the visible world, but also in possession of powers belonging to, or on the level of, the Anyitu. Thus, it is sometimes said of them, “anyitu u vit na” (half of him is anyitu).[38]

MINDORO

Pandaniwan (HANUNOO-MANGYAN)

The pandaniwan is the caretaker/guardian of a good spirit familiar called daniw. The Mangyan say that the malevolent spirits (labāng) are humans’ enemies because they eat their flesh and blood so that their “life principle” becomes one of the malevolent spirits. The benevolent dāniw ancestors (‘āpu dāniw) help to protect the humans against the labāng’s ill intentions. The role of the ritual specialist consists in maintaining the socio-cosmic relations that constitute the system which is based on the ‘āpu relation.[39]

Among the Mangyan groups, the terms balyán, balyán–an, and taong nagmamarayaw are also reportedly used. They also have other names for herbalists and hilots. There are variations in the folk beliefs among the different Mangyan groups ( Alangan , Iraya , Tadyawan , Buhid , Hanunoo).

MARINDUQUE

In Marinduque, Magtatawak are known as snake bite healers. They use various combinations of 150 plant species to create their healing combination of “tawak.” Collection of the plants and the making of concoctions are done during Holy week, starting Holy Monday. Preparation is accompanied by cultural traditions, like “usal and bulong” (incantations) which has been passed down over generations.[40]

SOURCES:

[1] Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas. Miguel de Loarca; (Arevalo, June, 1582)

[2] Boxer Codex, Transcribed and Edited by Isaac Donoso, Translated and Annotated by Ma. Luisa Garcia, Vibal Foundation, (2016)

[3] Customs of the Tagalogs (two relations). Juan de Plasencia, O.S.F.; Manila, (1589)

[4] Folk Medicine in a Philippine Municipality, F. Landa Jocano, PUNLAD Research House Inc., (2001)

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Bikol Maharlika, Jose Calleja Reyes, Goodwill Trading Inc, (1992)

[9] SHORT GLIMPSE ON THE ORIGIN, RELIGION, BELIEFS AND SUPERSTITIONS OF THE ANCIENT NATIVES OF BICOL by Fray Jose Castaño (1895)

[10] Bikol Beliefs and Folkways, Eden K. Nasayao, PhD, Hablong Dawani Publishing House, (2010)

[11] Ibid

[12] Power and Intimacy in the Christian Philippines, Fenella Cannell, Meyer Fortes, Edmund Leach, Cambridge University Press, (1999)

[13] The Muñoz text of Alcina’s History of the Bisayan Islands (1668), Lietz, Paul S., Philippine Studies Program, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Chicago

[14] The Enduring Ma-Aram Tradition, Alicia P. Magos., New Day, (1992)

[15] Ibid

[16] The Muñoz text of Alcina’s History of the Bisayan Islands (1668): Part I, book 3

[17] “An Exploration of the Ethno-Medicinal Practices among Traditional Healers in Southwest Cebu, Philippines” Fierro, Ramon S Del; Nolasco, Fiscalina A, ARPN Journal of Science and Technology. 3 (12): 7 (2013).

[18] Traditional Healers and Ritual Therapy in Bohol, Erlinda M. Burton, Research Institute for Mindanao Culture, Xavier University (1990)

[19] Arens, R. (1957). The Tambalan and his medical practices in Leyte and Samar Islands, Philippines. The Philippine journal of science, 86, 121-130.

[20] Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera, Cordillera Schools Group Inc., New Day Publishers, (2005)

[21] A People’s History of Benguet, Bagamaspad and Pawid, Baguio Printing and Publishing Company, (1985)

[22] Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera, Cordillera Schools Group Inc., New Day Publishers, (2005)

[23] Religion and Magic among the Isneg: Part II: The Shaman, Vanoverbergh, Morice, Anthropos, 48.(1953)

[24] The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe, Fay-Cooper Cole (1922)

[25] THE KALINGAS: Their Institutions and Customs Laws, Roy Franklin Barton, The University of Chicago Press, (1949)

[26] Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera, Cordillera Schools Group Inc., New Day Publishers, (2005)

[27] Ibid

[28] Tagbanuwa Religion and Society, Robert Fox, monograph 9, National Museum, (1982)

[29] “KABATAKAN” The Ancestral Territory of the Tanabag Batak on Palawan Island, Philippines, Dario Novellino, PhD, Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD), University of Kent – UK, and the Batak Community of Tanabag, (2008)

[30] Cleansing the Earth: The “Pänggaris” Ceremony in Palawan, Charles J-H Macdonald, Philippine Studies, Vol. 45, No. 3 (1997)

[31] The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao, Fay-Cooper Cole, FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY PUBLICATION 170, ANTHROPOLOGICAL SERIES VOL. XII, No. 2.(1913)

[32] The Bukidnon of Mindanao, Cole, Fay-Cooper, Martin, Paul S., Ross, Lillian A., Chicago Natural History Museum Press, (1956)

[33] The Wild Tribes of the Davao District, Fay-Cooper Cole, (1913)

[34] THE MANÓBOS OF MINDANÁO, John M. Garvan, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES, (1931)

[35] A Voice From Mt. Apo, Those Whom We Cannot See, Tano Bayawan, Linguistic Society of the Philippines (2005)

[36] The Traditional Maranaw Governance System: Descriptives, Issues and Imperatives for Philippine Public Administration, LIBERTY IBANEZ NOLASCO, Philippine Journal of Public Administration, Vol. XL VIII, Nos. l & 2 (January-April 2004)

[37] Dancing With the Ghosts of the Sea: Experiencing the Pagkanduli Ritual Of The Sama Dilaut (Bajau Laut) In Sikulan, Tawi-Tawi, Southern Philippines, Hanafi Hussin & MCM Santamaria, Jati, Vol. 13, (December 2008)

[38] Taming the Wind; Ethno-cultural History on the Ivatan of the Batanes Isles, Florentino H. Hornedo (2000)

[39] “To be in Relation; Ancestors” or the Polysemy of the Minangyan (Hanunoo)Term ‘āpu, Elisabeth Luquin INALCO (Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales, Paris) (2006)

[40] The Cultural Practices behind “Tawak,” a Traditional Cure for Snakebite in Marinduque. Lenni Grace L. Sapungan

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.