Mexico and the Philippines have ties that date back 400 years. It was said that this started when Spanish Governor General Miguel Lopez de Legazpi left the port of Natividad, Mexico to claim the Philippines as a Spanish colony. Because of the long distance from Spain, the Spanish Government represented by the Viceroy of New Spain (The capital of which was located in Mexico) was given the task of governing the Philippines. This governance ended when Mexico achieved independence form Spanish rule and covers a span of 257 years (1564-1821).

The contact flourished with the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade, which in turn gave a large cultural, religious, economic and ultimately human exchange from the coasts of Mexico to the Philippines. The remains of this contact are embedded in words, food and in some myths found in the Philippines.

Guanchiangos

Mexicans residing in the Philippines were called “Guanchiangos” derived partly from the Nahuatl-language word for “tree” (quauitl) and the suffix -an, which means “place”. A Guanchiango would therefore be someone who resides in the forest or jungle, this recalls the homeland of the Guanchiangos, the forested Mexico of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. These Mexicans were mostly troops that saw service in Cuba and the Philippines.

In certain stories collected by Dean Fansler in ‘Filipino Popular Tales’ the term “Guanchiango” would refer to a Mexican or a wandering beggar. It is possible that the Guanchiangos could have been remnants of the Mexican revolt against Spain, escaping to the Philippines through the ports of Veracruz and Acapulco.

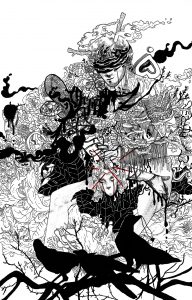

The Devil and the Guanchiango (Kapampangan)

There is an old Kapampangan folktale that deals with the Guanchiango.

There was once an old widow who had a lovely daughter named Piriang. The daughter was prideful as she said that she would rather marry the Devil than a poor man. The Devil heard of this and disguised himself as a handsome suitor, winning over the affections of Piriang and her mother. The suitor asked Piriang to remove the crucifix around her neck before the wedding, and sensing something wrong the girl told her mother. The mother went to the village church where the priest confirmed that the suitor was the Devil. The priest instructed the mother to show an image of the Holy Virgin to the suitor and when she did the Devil turned his back. The woman then tied her cintas (a kind of holy belt worn by women) around the Devil’s neck while Piriang struck him with a pagui (dried stingray) tail. The women forced the devil into a jar.

The next day a travelling Guanchiango passed near the house and the women asked him to bury the jar 21 feet beneath the earth. The Devil spoke to the Guanchiango from the jar though, convincing the Guanchiango to release him by telling the man that he would possess the princess of a nearby kingdom and then releasing her so that it would seem that the Guanchiango was the one that cured her. The Devil did not keep his part of the bargain, and in desperation the Guanchiango asked that all the bells of the nearby churches to be rung, which pushed the Devil away from the possessed princess. The Guanchiango eventually married the princess.

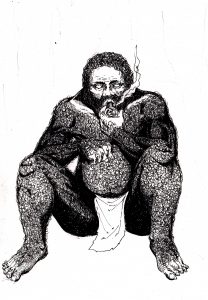

Death over the Devil (The Mexican version)

This story has obvious parallels to a story found in Mexico in a novelette, Macario written by Bruno Traven.

In the Mexican tale, a woodcutter makes a deal with Death itself, not the devil. The woodcutter, Macario, finds Death starving in a forest. Death is offered a morsel by the mortal, and in return gives the woodcutter the power to heal. Macario’s fame brings him to the palace where the viceroy’s son is dying. Death refuses to leave his position at the foot of the bed.

The Indian Origin

Both stories are derived from the same myth, one found in the Panchatantra. In the story, a Brahman befriends a demon who possesses a princess. The demon leaves the princess and enters the body of the maharani and refuses to leave. The Brahman is informed that his wife is returning by which time the demon (exorcised by the Brahman) disappears.

The story can be seen to have entered Spain through India during the Middle ages, probably by the Arabs as the definitive Spanish version is found in Andalucia, which was under Moorish rule for centuries. From there the story entered Mexico through the conquistadors, most of which came from Seville, which was the port of commerce with Mexico.

Comparing the Myths

While the two stories have obvious differences, it can be seen as a reflection of the culture in each area. The Kapampangan version, with its Catholic sensibilities and layer of local myth (with the pagui tail), contrasts to the Mexican obsession with Death that has characterized the culture since early times.

Myths change depending on the time, space and culture of the people that tell it. The Brahman in the Hindu version was transformed into the Guanchiango of the Kapampangan tale, who was the woodcutter in the jungles of Mexico.

Fansler and the Oaxacan Connection

It was Dean Fansler who first found the similarities between Oaxacan (Southern Mexican) and Philippine folktales. This connection is important because Oaxaca is in the middle of the Guanchiango area close to Acapulco, the main galleon trade port.

Many Philippine folktales have Oaxacan counterparts (The Philippine Folktales can be found in Fansler’s Philippine Popular Tales).

In the story The Rich and the Poor, two friends, Mahirap and Mayaman argue on how to make a poor woodcutter rich. The gifts of Mayaman are lost by the woodcutter but the few centavos given by Mahirap help him recover all he lost. In the Oaxacan version of the story a rich compadre loans money to a friend, who subsequently loses it. In contrast to the Philippine version there is a moral “El que nazca pobre, siempre sera pobre” (He who is born poor, will remain poor). The fatalism in the Mexican version is an example of the cultural difference between the two nations, the Philippine version of the story would have a higher chance of a happy ending.

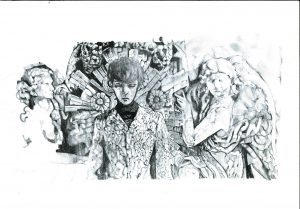

Kapres in Mexico?

The Kapre is a mythical creature well known in Philippine lore. It is described as a gigantic, black man living in trees or abandoned houses. The term kapre comes from Arabic and means one who does not believe in the tenants of Islam. The word is traceable to India where the words bhut (pugut) and kafari (kapre) mean the ghosts of murdered dark skinned people.

Fansler recorded the legend of Pugut Negru which is a Spanish romance involving Moors (Muslims). There is a parallel creature in Oaxaca called H’ik’al, literally meaning ‘the black man’, it is described as having curly hair and characteristics similar to black slaves in the area. The origin of the H’ik’al can be connected with the Mayan bat god Tlacatzinacantli, but there are also stories that say it was inspired by the presence of black slaves and workmen in the area.

In this case the parallelism of the myths can be attributed to similar conditions in both Oaxaca and Pampanga (the presence of black slaves and workmen).

Mexico and the Philippines

The myths compared here are just a few examples of the similarities found in the stories of the two countries. The similarities can be attributed to the wide-scale cultural contact that happened during the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade. Other stories include the similarities between La Llorona and La Loba Negra, the legend of the volcanoes Popocatepetl and Ixtaccihuatl compared to the legend of Mt. Mayon and many others.

Source: Filipino Heritage The Making of a Nation Volume 5. Myths Shared With Mexico by John W. Burton. Pg 1276-1283.

ALSO READ: FOREIGN INFLUENCE | Understanding Philippine Mythology (Part 3of 3)

Speculative fiction writer. Philippine folklore and heritage researcher.

Author of The Spirits of the Philippine Archipelago.

Currently in the middle of fixing up an encyclopedia of Philippine Mythical creatures.