Ages before the appearance of Spain in Southeast Asia, the (now known as) Filipinos had commercial, political, and cultural relations with India, China, Japan, Arabia, and Malaysia. Unfortunately, many facts about this early period of Philippine history are still unknown so that our comprehension of it is rather vague. Historical research in recent times, however, aided by archaeology, ethnology, and folklore,[1] has given us concrete, although fragmentary, facts which cast some light on the opaque dawn of Philippine history.

This article aims to give readers an introduction to the influences on the area now known as the Philippines to assist in understanding the building blocks of precolonial religions before the Spanish arrival.

Prehistory: The First Arrivals

The history of the Philippines is believed to have begun at least 709,000 years ago as suggested by the discovery of Pleistocene stone tools and butchered animal remains associated with hominin activity. Homo luzonensis, a species of archaic humans, was present on the island of Luzon at least 67,000 years ago. The earliest known modern human was from the Tabon Caves in Palawan dating about 47,000 years.

Negrito groups were the first inhabitants to settle in the prehistoric Philippines. The term Negrito (often considered a misnomer) refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations classified as Negrito include: the Andamanese peoples (including the Great Andamanese, the Onge and Jarawa and the Sentinelese) of the Andaman Islands, the Semang peoples (among them, the Batek people) of Peninsular Malaysia, the Maniq people of Southern Thailand. In the Philippines, they are the Ati of Panay Island, the Aeta of Luzon, the Batak of Palawan, the Agta of the Sierra Madres and the Mamanwa of Mindanao. They are among the first settlers of the archipelago.

Based on perceived physical similarities, Negritos were once considered a single population of closely related people. However genetic studies suggest that they consist of several separate groups, as well as displaying genetic heterogeneity. The Negritos form the indigenous population of Southeast Asia, but were largely assimilated into the later arriving Austronesian settlers. The remainders form minority groups in geographically isolated regions. Most were hunter–gatherer societies. Today they are found in various stages of deculturation, and most are involved in agriculture. “Negrito” populations were animistic. They believed that everything has a spirit, from rocks and trees to animals and humans to natural phenomena. Many ‘negrito’ beliefs structures evolved to include deities and creation myths.

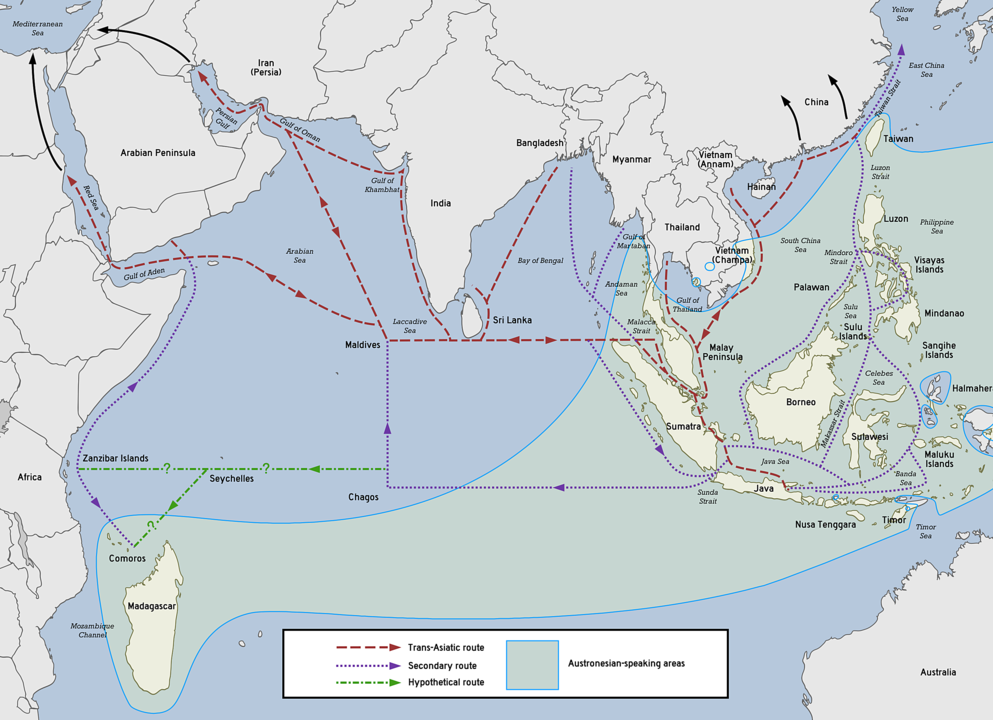

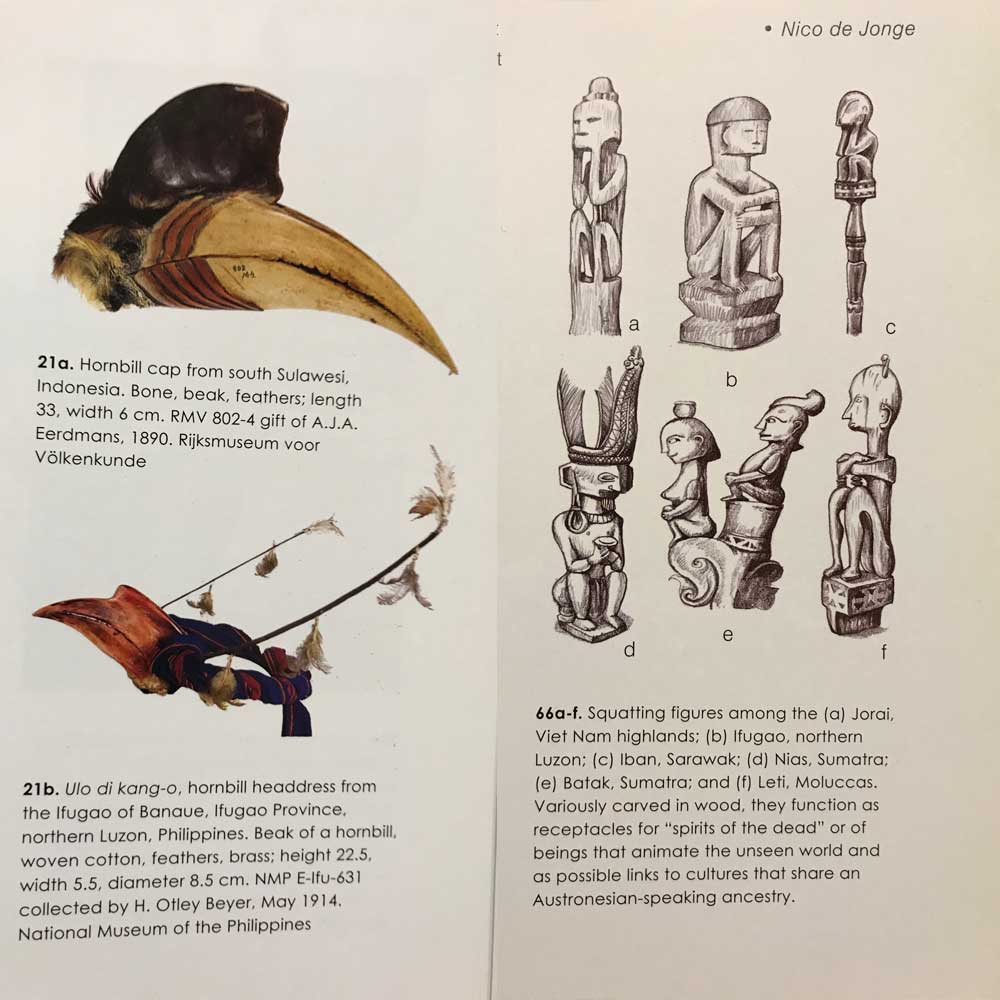

Ancient Austronesians were also animistic. The spirits in their belief structures are collectively known as anito, derived from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *qanitu and Proto-Austronesian *qaNiCu (“spirit of the dead”). Cognates exist in many other Austronesian cultures. Anito can generally be divided into two main categories: the ancestor spirits (ninunò), and deities and nature spirits (diwata). Generally, these indigenous folk religions are referred to as Anitism or the more modern and less Tagalog-centric Dayawism.[2]

The Austronesian expansion theory is under constant evolution and we have been learning that the movement of seafaring people during this period of time is infinitely more complex that the simplified “Out of Taiwan” model. However, there is no doubt that ancient Austronesians were the main cultural influence to the area now known as the Philippines. Part of their success was the ability to sustain settlements through agriculture and the domestication of animals. Agriculture and creating a surplus of food to be distributed had a massive impact on the social sphere. Since there was no need for all villagers to devote themselves full time to finding food as with hunter-gatherer societies, specialization within society was made possible. This would include warriors, leaders, builders, artisans, healers and shamans. Since a static society was reliant on their particular environment, religious beliefs began including a complex pantheon of spirits and deities that managed weather, health, crops, and the human affairs associated with a successful village. Stories of culture heroes were introduced in the mythology of the region and were used as benchmarks for the ethics and morals of the people. These were likely used to create laws and ritual. These rituals were an important function in aligning personal identities with social roles.

There is a profusion of different terms and particularities that arise from the fact that these indigenous religions mostly flourished in the pre-colonial period before the Philippines had become a single nation.[3] The various peoples of the Philippines spoke different languages and thus used different terms to describe their religious beliefs. While these beliefs should be treated as separate religions, scholars have noted that they follow a “common structural framework of ideas” which may be understood together.[4] The various religions of Oceania and the maritime Southeast Asia, also draw their roots from similar Austronesian beliefs as those in the Philippines.[5] This foundation is prevalent when comparing cultures that include tattooing, totemism, shamanism, and is seen in weaponry, art, textiles, ritual, myths and dress. A stronger understanding of this foundation may be gained from studying the various ethnic groups living in the northern part of the Philippines, known collectively by the exonym ‘Igorots’ but include the Bontoc, Ibaloi, Ifugao, Kalanguya/Ikalahan, Isneg, Itneg/Tingguian, Kalinga, and Kankanaey peoples.

While the foundational base of beliefs can be formed from an understanding of ‘Austronesian Animism,’ other religious influences contributed to the sculpting of very unique religious structures among each ethnolinguistic group throughout the archipelago. The folklore narratives associated with these religious beliefs constitute what is now Philippine mythologies, and is an important aspect of the study of Philippine cultures.

*NOTE: The terms “Filipino” and “Philippines” are used throughout this article with the knowledge of their history. They will be used in the precolonial setting for clarity of the modern regions we are speaking of.

Piecing Together Recorded History.

In chronicling pre-Spanish epochs, historians must grapple with the mighty problem of scarcity of written records. The Filipinos of the past wrote on biodegradable materials, such as tree bark, bamboo, boards, and leaves of plants, which could not withstand the ravages of time, or the effects of earthquakes, typhoons, and other natural cataclysms; hence, their ancient writings perished. The pioneer Spanish missionaries, inspired by their apostolic zeal to propagate Christianity, burned certain native manuscripts, thus contributing to the destruction of the old written records.[6]

Aside from the paucity of Philippine writings, there exist few archaeological relics in the country.[7] There are no colossal pyramids as in Egypt, no buried cities as in Babylonia, no temple ruins as in India, and no rocky inscriptions as in Central America. In the absence of such archaeological remains, historians are sorely handicapped in their task of reconstructing the Philippine past.

To get a glimpse of the hazy frontiers of Philippine history, we must turn first to the neighboring countries of Asia, whose old historical records mention certain relations with the Philippines.

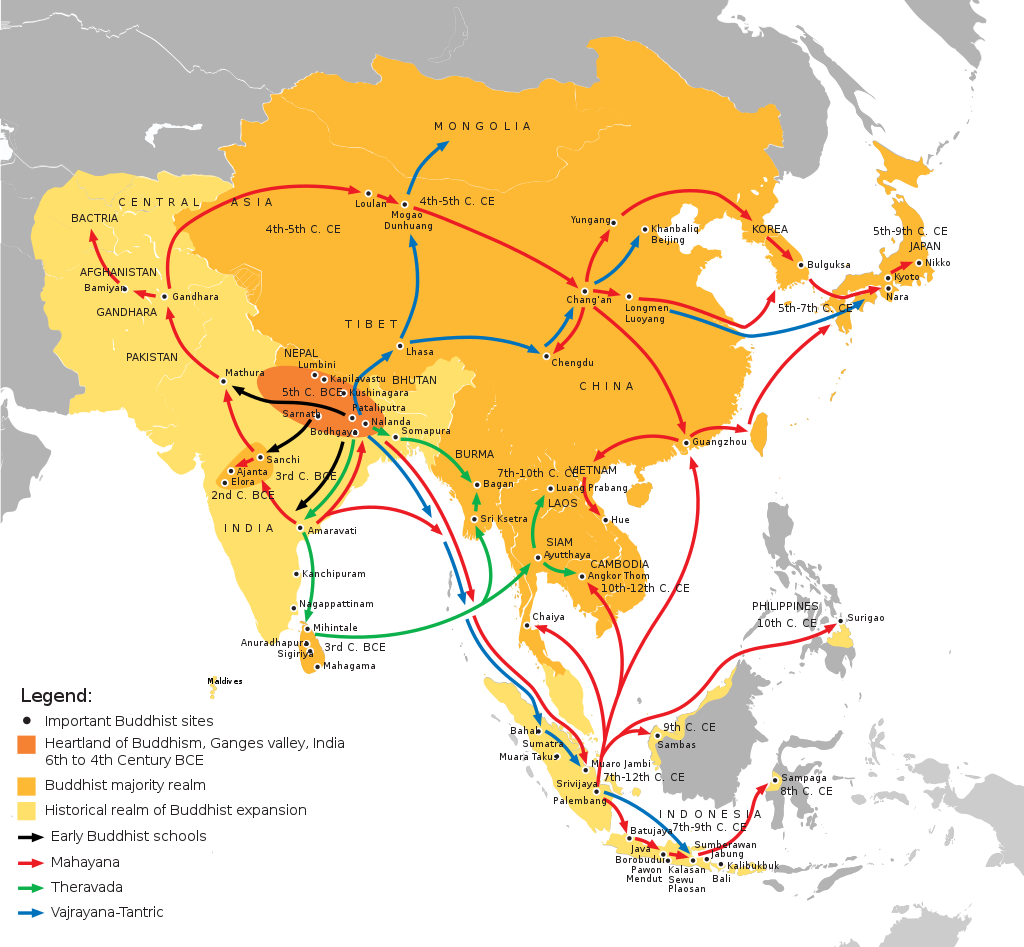

Early Relations with India.

Long before the Christian Era, India was an advanced civilization which was the product of the genius and might of its people. At that time when Europe, excepting Greece and Rome, was enveloped in barbarism, India was already dotted with powerful kingdoms and teeming cities, was embellished with temples and marble edifices, and had highly developed arts and sciences, including philosophy, literature, mathematics, Sanskrit writing, and several religions, notably Brahmanism and Buddhism.

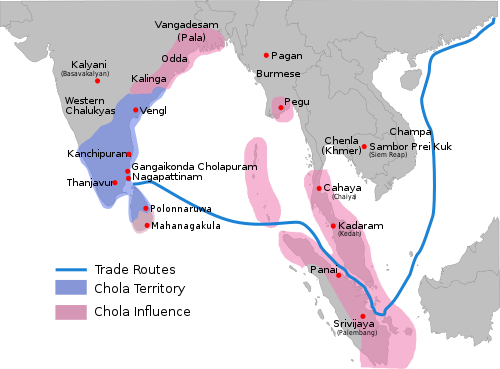

Towards the close of the 2nd century A. D., the Pallava dynasty arose in the eastern coast of India around the mouth of the Penner River.[8] This dynasty expanded by conquering the other kingdoms of southern India and Ceylon; and, as it skyrocketed to political hegemony, its maritime colonizers and conquerors went overseas and established colonies in the Malay Peninsula, Champa,[9] Cambodia, Java, Sumatra, and other islands in the Malaysia Peninsula. These colonies served not only as outposts of Pallava power, but also as centers of Asian commerce and seats of Hindu civilization.[10]

In the 8th century CE, the Pallava dynasty declined because of the rise of other rival kingdoms. In 740 CE the Pallavas suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Chalukya dynasty. Later, in the closing years of the 9th century, the warrior-king of the Cholas named Aditya formed a confederacy of three kingdoms – Chola, Chera, and Pandaya, and completed the destruction of the Pallava power. Over the ruins of the Pallava colonies in Southeastern Asia arose various independent states, notably Cambodia, Champa, Sri Vishaya, and Madjapahit. Through the Hinduized empires of Sri-Vishaya and Madjapahit, the civilizational influences of India streamed towards the Philippines and affected the ancient Filipino way of life.

The Sri-Vishaya Empire.

The empire of Sri-Vishaya[11] emerged from the ashes of Pallava’s maritime colonialism and dominated the area now known as Malaysia from the 8th century to 1377 CE[12] Founded by Hinduized Austronesians, it was basically Austronesian in might, Hindu in culture, and Buddhistic in religion. The empire was so named after its capital, Sri Vishaya, Sumatra. At the height of its power under the Shailendra dynasty, “it included Malaya, Ceylon, Borneo, Celebes, the Philippines, and part of Formosa, and probably exercised suzerainty over Cambodia and Champa (Annam).[13]

The two main centers of Sri-Vishayan influence in the Philippines were Sulu and the Visayas. Both places were colonized from Borneo, a tributary state of Sri-Vishaya. The colonists from Banjarmasin, Borneo, settled Sulu and their princess married the Sulu king. In the middle of the 13th century, according to the controversial Maragtas work, ten Bornean datus led by Datu Puti left Brunei and colonized Panay. It is believed that the Maragtas story is an original work by Pedro Alcantara Monteclaro, based on available written and oral sources.

In the 13th century, the imperial sway of Sri-Vishaya began to wane on account of the rising power of another Hindu state in Java, known as the Madjapahit Empire. The complete downfall of Sri-Vishaya, as a result of the assault of Madjapahit arms, occurred in 1377.

Featured in the exhibition ‘Gold of Ancestors: Pre-colonial Treasures of the Philippines’ (Permanent Display) Image courtesy of Neal Oshima and Ayala Museum

The Madjapahit Empire.

The Madjapahit Empire,[14] heir to Sri-Vishaya’s grandeur, was present in Southeast Asia for about two centuries. It was founded as a little kingdom in Java in the year 1293 by Raden Widjaya, celebrated Javanese conqueror, who expelled the Chinese forces sent by Kublai Khan to subjugate the island. Like Sri-Vishaya, it was Austronesian in might and Hindu in culture, but in religion it was Brahmanistic.

From its capital at Madjapahit, Java, the new empire extended its sovereignty over the former colonies of Sri-Vishaya and other territories, such as Formosa, Siam, Cambodia, Indo-China, Southern Emma and New Guinea.[15] The regions in the Philippines where its power was strongly felt were (1) the Manila Bay district in Luzon, (2) the Sulu Archipelago, and (3) the Lanao district in Mindanao.

One of the great rulers of Madjapahit was a woman named Suhita. This Javanese queen was a woman of remarkable sagacity and administrative ability. Their prime minister was Gadja Mahda, the famous Javanese statesman. Madjapahit reached the zenith of its power about the middle of the 14th century during the reign of Hayam Wuruk, the warrior-statesman. After his death in 1389, the signs of decay appeared. A bitter dispute arose with respect to succession to the throne, culminating in a bloody civil war. Another cause of its decadence was the naval expeditions of Cheng Ho, famous Chinese admiral, to Malaysia from 1405 to 1434, which encouraged many colonies to renounce their allegiance to the Madjapahit ruler and to seek the nominal suzerainty of China.

Madjapahit was overthrown in 1478[16] by the Islamic inhabitants under Sunan Bonang, famed son of the famous Sunan Ampel (born Raden Ahmad Rahmatullah) of Champa.[17] This marked the end of Hindu influence in Malaysia and the beginning Islamic supremacy. Over Madjapahit’s ruins arose the Islamic Empire of Malacca which, in turn, struggled during the attacks of the European powers in the 16th century.

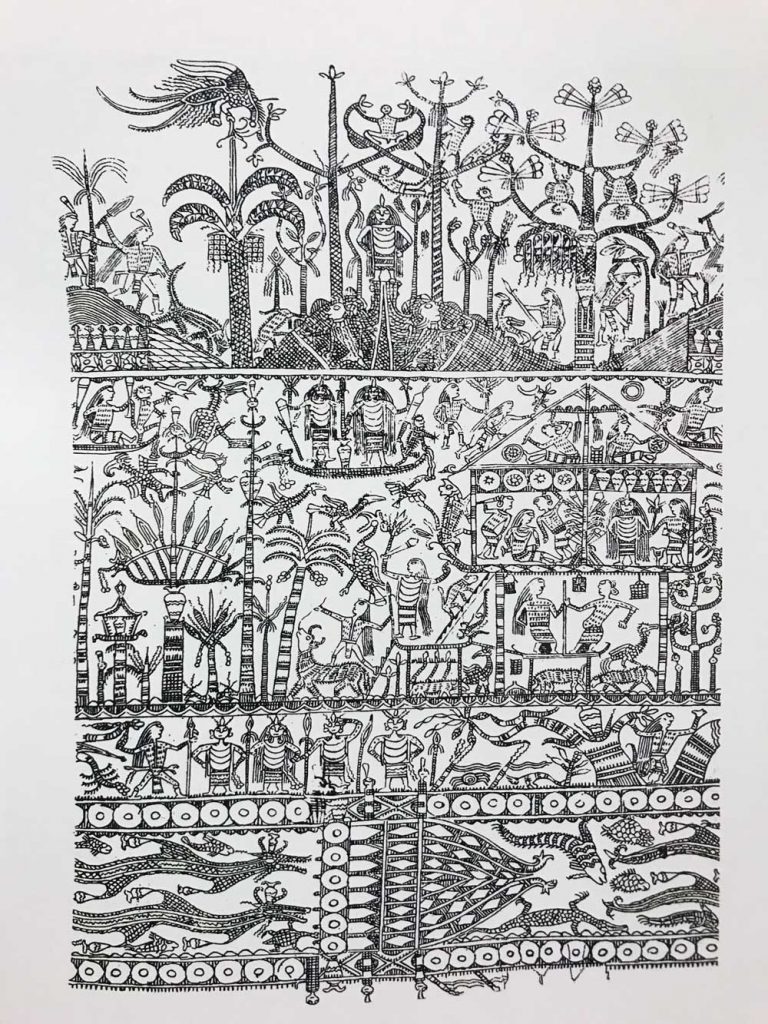

The influences of Hinduism and Buddhism is evident in early documentation of the cultures and religions among the Tagalogs, Visayans, Bicolanos and is still seen among the indigenous people of Mindanao ( Bagobo, Bukidnon, Mandaya, Manobo, T’Boli and others) and indigenous people of Palawan. Perhaps most prevalent in the religious structures influenced by this period are the concepts of diwatas and demons (the latter often referred to as buso or aswang). Also present are the remnants of myths, epics, and legends influenced by the great Indian epics, Mahabharata and Ramayana.

Image from OUTLINE OF PHILIPPINE MYTHOLOGY by F. Landa Jocano (1969)

Artist uncredited

Early Relations with China.

Sino-Philippine relations antedated the advent of the Europeans in Southeast Asia. This fact is supported by archaeological relics, such as the rare Sung and Yuan porcelain and fragments of ancient Chinese pottery[18] found in the Philippines, and by historical passages from the old Chinese documents and dynastic annals. According to Terrien de Lacouperie, the Chinese, as early as 200 CE,[19] had knowledge of the Philippines. He said also that the country was mentioned in the Chinese Annals of 628 and 636 CE It is related that at about 800 CE a band of Chinese explorers and adventurers visited the Philippines because of the lure of gold.

The first authentic date in early Sino Philippine relations was 982 CE, as found in an old Cantonese document.[20] In that year some Filipino traders visited Canton for purposes of trade. By the 10th century the trade between the Philippines and China was already well-established. The Chinese trade junks visited Ma-i (Mindoro), San-hsu (Central Visayas), Liu-sung (Luzon), Pa-lao-yu (Palawan), and Pu-li-lu (Polillo).

The Chinese writer Chao Ju-kua, in his work Chu-Fan-Chi written between 1209 and 1214, described the Chinese trade with the Philippines and praised the honesty of the Filipinos. Writing in 1349, his compatriot Wang Ta-yuan re-affirmed the fact that the Filipinos were honest in their dealings with the traders from Cathay.

The early Chinese trade junks brought to Philippine shores not only cargoes but also immigrants. According to a Chinese writer of modern times, Ta Cheng, the Chinese overseas migrations to Malaysia and the Philippines began in the 7th century CE and reached their peak after 1644 owing to the Manchu conquest of China.[21] The Chinese immigrants settled in Manila and other ports which were annually visited by trade junks from their homeland. Some of them brought their wives; many, however, did not bother to burden themselves with women from their own home country and readily married Filipino women. When Goiti captured Manila in 1570, he found some Chinese women among his prisoners; these were the wives of the Chinese settlers who had fled with Sulayman’s warriors.[22] In 1571 Legazpi found in Manila a Chinese colony of 150 men and women. “These Chinese,” related an anonymous chronicler of his expedition, “live among these natives [of Luzon-Z.] because they have fled from their own country, on account of certain events which took place there; all of them, both men and women, number about one hundred and fifty.”[23]

China’s Nominal Sway over the Philippines.

For a brief period under the Ming dynasty (1399-1644), China exercised some sort of nominal suzerainty over the Philippines. According to the Ming-shih (dynastic annals of the Mings), the Filipinos paid tribute to China.[24] The first tribute embassy from the Philippines reached the Chinese court in 1372. Emperor Hung-wu, in reciprocation, dispatched a Chinese official to the Philippines with gifts of silk and porcelain vases for the native chieftains. In 1417 Paduka Pahala, the king of East Sulu, died in China, and he was accorded a state funeral by Emperor Yung-lo. His tomb is preserved to this day outside of Peking. To maintain its power throughout Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, China sent officials and naval patrols to remind the native rulers of their allegiance to the Son of Heaven. In 1405 a Chinese governor named Ko-ch’a-lao was dispatched to Luzon by Emperor Yung-lo.[25] A mighty Chinese fleet, under the command of the famous admiral Cheng Ho, visited Lingayen, Manila, Mindoro, and Sulu in 1406-07, 1408-10, and 1417, as well as Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and other islands in Southeast Asia.[26] By the shores of Indanan, Sulu, today, there is a tomb which serves as an enduring monument of the Ming rule over the Philippines. This is the tomb of Poon Tao Kong (born 1403), a member of a Chinese mission to Malaysia.

The last Filipino tribute embassy came to China in the year 1421, according to the Ming-shih. After this time, the Chinese emperor withdrew China’s nominal sovereignty and left the Filipinos to their own political fate.[27] Notwithstanding this political separation, however, China and the Philippines continued their commercial and cultural relationship, which exists to the present day.

Possible Early Relations with Japan.

Philippine contact with Japan may have antedated the advent of Spain in Southeast Asia. Asian pundits are inclined to believe that Filipinos and some Japanese are racially related because settlers of southern Japan were of Austronesian origin.[28] It is claimed by ethnologists that the maritime Austronesians, in their prehistoric exodus over the Pacific world, reached as far as Formosa and southern Japan. Historical records also show that Japanese pirates (wako) kingdom-builders, and settlers had come to Luzon before and immediately after Spanish colonization. The early Spanish conquistadores encountered them at various places in the island. In 1572 Captain Juan de Salcedo, on his way to Ilocos, fought three piratical Japanese junks[29] off the coast of Pangasinan. And in 1582 Governor-General Ronquillo (1580-83) sent a strong Spanish expedition under the command of Juan Pablo Carrion to Cagayan where a Japanese kingdom had previously been founded by Tayfusa (Zaifusa). This expedition succeeded in driving away the Japanese after a bitter fight at the mouth of the Tajo (Cagayan) River.[30] Japanese traders, especially those from Nagasaki, frequently visited Philippine shores and bartered Japanese goods for Filipino gold, pearls, and native earthen jars.[31] Certain shipwrecked Japanese sailors and immigrants settled in the Philippines and intermarried with the Filipinos. According to Japanese records, the early Spaniards found Japanese settlements in Manila and in Agoo, La Union Province.[32]

Early Relations with the Arab World.

History suggests that Arab relations with Southeast and East Asia began as early as the time of King Solomon.[33] During that period the Sabaean people (known as Sheba in the Bible) in southern Arabia were the greatest carriers of maritime commerce in Asia Minor and India. The first century of the Christian Era saw their ships making periodic trading voyages through Southeast Asian seas to China; in the third century they established a trading colony at Canton; and in the ninth century their ships visited Kedah in the Malay Peninsula, Java, Sumatra, and the Moluccas. According to Raymundo Geler, using ancient Arabian sources, the early Sabaean people, in the course of their trading voyages to China, visited various places in the Philippines, notably Paragua (Palawan), Mindanao, Calamianes, Visayas, Mindoro, and Luzon.[34] It should be noted that these Arabs were non-Muslims and that they were traders, not religious proselytizers.

Introduction of Islam.

After Mohammed’s death (632 CE), the Sayyids from the Arabian Peninsula carried the torch of Islam to the islands of Southeast Asia. These Sayyids, claiming descent from Fatimah, Mohammed’s daughter, were men of courage and learning. By intermarriages with the native ruling families and by political machinations, they eventually gained control of the Malay states, and, once in power, they spread intensely the doctrines of Islam. By 1276, the new faith was rooted in Malacca. This city, founded in 1380 by refugees from Sri-Vishaya, became the citadel of Islamic influence and, subsequently, the capital of the Islamized Malaccan Empire, heir to the Hinduized Madjapahit Empire.

In 1380, according to the tarsilas (Moro chronicles), the Arab missionary-scholar Sheikh Karim-ul Makhdum, fresh from his proselyting triumphs in Malacca, landed at Sulu and there laid the foundation of Islam in the Philippines.[35] Ten years later, in 1390, Rajah Baguinda, prince of Minangkabau Sumatra, came with his forces to Sulu. He easily overcame native opposition because his warriors used firearms, which were believed to be the first firearms used in the Philippines. In 1450 Abu Bakr, Islamic leader from Palembang, Sumatra, recached Sulu and married Dayang-dayang Paramisuli, the daughter of Rajah Baguinda. After Baguinda’s death, he founded the sultanate of Jolo, with himself as sultan. He “remodeled the government after the pattern of an Arabian sultanate, giving himself all the powers of a caliph.”[36] He gave the people a new code of laws which reconciled the local customs with Qur’anic law. He died in 1480 after a prosperous reign of 30 years.

The Islamic conquest of Mindanao was attributed to Shariff Muhammed Kabungsuwan,[37] Muslim leader of Johore in Maritime Southeast Asia. In 1475, he landed in Cotabato and gained influence through force and other interactions with its native people. He married a native princess named Putri Tunina, and became the first Islamic sultan of Maguindanao.

From Sulu and Mindanao, Islam was borne across the Visayas to the northern islands of the Philippine Archipelago and was introduced in Mindoro, Batangas, and the Manila Bay region. Islamization was a slow process characterised with the steady conversion of the citizenry of Tondo and Manila which created Muslim domains. In 1571 Manila was an Islamic polity under Rajah Sulayman, a Muslim Tagalog king. Across the Pasig River was Tondo, another Islamic polity under Lakan-Dula. While Spanish records suggest that the Manila area was Muslim (Moro), the inhabitants still likely practiced a form of Anitism syncretized with Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam.[38] The Islamic foothold in Manila may have been overstated by the Spanish in their zeal to record a religious victory.

Spain’s Arrival Interrupts Islamic Expansion.

From the shores of Manila Bay, Islam likely would have likely gained a stronger foothold around Manila and expanded farther north, but clashes with the arriving Spanish forces halted this progress. The bloody clash between King Sulayman and the Spaniards in 1570-71 was not only a political struggle between the Spanish and Filipino warriors for mastery of the land, but also a religious war or miniature crusade; it was likely seen by the Spanish as a fight between the Cross and the Crescent for supremacy. The triumph of the Spaniards over Sulayman’s warriors meant, to the Spanish, the victory of Christianity over Islam.

It was thought that the arrival of Spain stopped the northward advance of Islam.[39] Following its reverses in Luzon, Islam retreated to Sulu and Mindanao where it has remained to the present day. It has successfully defied more than three centuries of Catholic Spain’s efforts and more than four decades of Protestant America’s attempts to dislodge it from the hearts and minds of its worshippers.

Pre-Islamic religious beliefs and rituals became part of Muslim ceremonies in much of SE Asia. They were mostly tolerated until a global Islamic revivalism swept the world in the late sixties and early seventies. Today, Muslims in the Philippines are mostly located in Mindanao. There are thirteen Muslim tribes: the Iranun, Magindanaon, Maranao, Tao-Sug, Sama, Yakan, JamaMapun, Ka’agan, Kalibugan, Sangil, Molbog, Palawani and Badjao. Collectively, they are also known as the Bangsamoro people. Indian influences are still seen in the epics, dance, music and myths in many of the Bangasamoro cultures.

Illustration by Mike Lombo Jr. (Tales from our Malay Past)

Early Relations with Other Asian Countries.

Prior to the coming of the Spaniards, the Philippines had commercial relations with Siam, the Moluccas, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Java, Sumatra,[40] and the other islands of Malaysia. In 1521 Magellan found a Siamese trader in Cebu.[41] Later, in 1565, Legazpi captured near Bohol a native pilot who was “a most experienced man who had much knowledge, not only of matters concerning these Filipinas Islands, but those of Maluco (Moluccas), Borneo, Malaca, Java, India, and China where he had much experience in navigation and trade.”[42] An interesting Spanish document of 1586, further verifying the ancient commercial relations of the Filipinos with their Asian neighbors, stated: “They [Filipinos – Z.] are keen traders and have traded with China for many years, and before the advent of the Spaniards, they sailed to Maluco, Malaca, Hazin (probably Achen in Sumatra), Parani, Burnei, and other kingdoms.”[43]

A very short summary of the above can be seen in the video below.

For further reading, please see the other articles we have published on the topic or visit the highlighted text to read other articles expanding on the topics.

SOURCES and NOTES:

[1] In the reconstruction of a nation’s ancient history, the historian is forced, by dearth of historical sources, to utilize the findings of archaeology, ethnology, and other auxiliary sciences. All human sciences, in truth, are interrelated; they complement, implement, and supplement one another. For an illuminating discussion of this interdependence of the sciences, see Max Nordau, The Interpretation of History (London, 1910, English translation by M. A. Hamilton); Harry B. Barnes, The New History and the Social Studies (!New York, 1925); and C. V. Langlois and C. Seignobos, Introduction to the Study of History (New York, 1932.)

[2] Demetrio, Francisco R.; Cordero-Fernando, Gilda; Nakpil-Zialcita, Roberto B.; Feleo, Fernando (1991). The Soul Book: Introduction to Philippine Pagan Religion. GCF Books, Quezon City.

[3] Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

[4] Sitoy, T. Valentino, Jr. (1985). A history of Christianity in the Philippines Volume 1: The Initial Encounter. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers.

[5] Osborne, Milton (2004). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History (Ninth ed.). Australia: Allen & Unwin.

[6] For the sake of historic truth, it must be noted that the early Spanish chroniclers admitted that the Spanish missionaries burned Filipino idols and records to accelerate the spread of the Gospel. The famed Jesuit historian, Fr. Pedro Chirino, recounted the burning of a Filipino book of poetry called Golo by a missionary. (Relacion de las Islas Filipinas. Rome, 1604, p. 47.) But it is certainly, unfair and untrue to blame the missionaries wholly for the loss of the written records (as many writers rashly do), for the missionaries could not possibly have destroyed all the records in more than 7 ,000 islands of the archipelago.

[7] “The Philippine Islands,” thus stated Dr. Najeeb M. Saleeby, noted authority on Malayan affairs, “are exceedingly poor in archaeological remains.” (Origin of the Malayan Filipinos. Manila 1912, p. 5.)

[8] Malayan Filipinos. Manila 1912, p. 5.) “This state the kingdom of Pallava,” wrote Prof. G. Nye Steiger, “first gave evidence of its real power about the year 225, when its armies invaded the territory of the Andhra kingdom and inflicted upon the Andhras a defeat which coupled with simultaneous developments in the nor h, caused the downfall of that once powerful empire. After this a auspicious beginning the Pallavas steadily, expanded their power at the expense of their neighbors on the south, and King Simhavishnu in the closing years of the sixth century claimed to have conquered the rulers of Pandaya. Chola, Chera, and Ceylon.” (A History of the Far East. Boston , .1936, pp· 148- 149.) An excellent source on the history of the Pallava Kingdom 1s G. Jouveau- Dubreiul. The Pallavas (Pondicherry, 1917).

[9] According to tradition, Champa was founded by Cambu Svayambuva, who was said to have come from Arya Deca (ancient name for India).

[10] Vide R. C. Majumdar, Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East (Lahore, 1927); P. Bose, The Indian Colony of Champa (Adyar, 1926) ; P. Bose, The Hindu Colony of Cambodia (Madras, 1927) ; and Jawaharlal Nehru, The Discovery of India (New York. 1946), pp. 195-196.

[11] For good accounts of this empire, see G. Ferrand, “L’Empire Sumatranais de Crivijaya,” Journal. :Asiatique, 1922; R. 0. Winstedt, A History of Malaya (Singapore, 1935), pp. 22-26; H. Otley Beyer, “The Philippines Before Magellan,” Asia, October, 1921; Steiger, A History of the Far East, pp. 194-199; E. S. de de Klerck, History of the Netherlands Indies (Rotterdam, 1938 ) , Vol. I, pp. 126- 139; and .Tawaharlal Nehru, Glimpses of World History (New York, 1942), pp. 101-103, 133-137.

[12] “The earliest accounts of srivijaya,” said Dr. F . M. Schnitger, Dutch archaeologist and Conservator of the Museum at Palembang, Sumatra, “date from the end of the seventh century.- It seems to have attained its greatest glory during the eighth to the eleventh centuries: during the thirteenth century ii declined and in 1377 was conquered by the .Javanese.” (Vide ” Unearthing Sumatra’s Ancient Culture.” Asia, March, 1938. )

[13] Nebru, The Discovery of India, p. 199.

[14] For good accounts of this empire, see Windstedt, op. cit., pp. 26-36; Beyer. “The Philippines Before Magellan ,” loc. cit., October . 1921; Steiger, op. cit., p p . 330-333; Aristide Marre. Madjapahit et Tehampa (Louvain, 1895) pp. 1-10; and Nehru. Glimpses of World History, pp. 263-268.

[15] For some forty years,” wrote Professor Steiger, “after t he .’destruction of Kediri (1293), the power of Madjapahit was confined to the island of Java. About 1331, however, the .Javanese kingdom began to extend its authority over some parts of the Malay world. By 136,1 Madjapahit had subjugated its neighbors on the east as far as the western portion. of New Guinea, was in control of Borneo and the greater part of the Philippines on the northeast. and ruled over all Sumatra except the ancient. capital of Sri-Vishaya. Jn 1377 the city of Sri-Vishaya was

finally conquered, and about the same time Madjapahit succeeded in establishing its power over t he southern part of the Malay Peninsula.” (A History of the Far East, p. 331.)” Cf. Marre .. 011. cit. , pp. 3-8.

[16] Marre . Madjapahit et Tchampa, p . 10.

[17] The last descendants of Madjapahit’s uling family fled to the island of Bali and lived there in retirement. Today this island is famous for its beautiful women and its picturesque Buddhistic temples. A strict law, said to be originally enforced by the fugitive royalty of the fallen Madjapahit empire, still exists -· prohibiting any Mohammedan from settling foot on the island.

[18] F ay Cooper Cole , Chinese Pottery in the Philippines. Chicago, 1912. Yield Museum of Natural History Publications No. 162.

[19] Formosa . .Notes on MSSSS., Races and Languages ( London, 1887), pp. 44

[20] Henry St. Denis. E thnoqraphie, Vol. II. p. 502. Cited by Austin Craig, A Thousand Years of Philippine History Before the Coming of the Spaniards (Manila, 1914), p . 6. That the ancient Filipinos used sail to China is evidenced by Spanish sources. Writing from Pa ay, .July 25, 1570, :Miguel Lopez de Legazpi reported to King Philip II: ” These Moros [Luzon Filipinos- Z.] have much more trade because they make voyages for that purpose, going among the people on the Chinese mainland, and to the Japanese.” (Blair and Robertson, The Philippine lslands , Vol. III. p . 110.)

[21] Vide “Chinese Migrations.” Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor. Washington D.C.. 1923. No. 340 p . 4.

[22] See. Relation of the Voyage to Luzon, May 8, 1570,” Blair and Robertson. The Philippine Islands , Vol. III. p. 102. On the way to Manila. Goiti captured two Chinese junks off the coast of Mindoro; he treat ed the Chinese prisoners well and set them free, and again at Manila Bay he found four Chinese junks. (Blair and Robertson, op. cit., Vol. III, pp. 7Fi-77, 95.)

[23] Vide “Relation of the Conquest of the Island of Luzon, April 20, 1572, .. Blair and Robertson, op cit., Vol. III. pp. 167-168.

[24] Berthold Laufer, 7’he Relations of the Chinese to the Philippine Islands. Washington, D. C., 1907. The Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 50, Part 3, No. 1734

[25] H . Otley Beyer, Historical Introduction,” E. Arsenio Manuel, Chinese Elements in the Tagalog Language. Manila, 1948, p . x iv.

[26] Ibid., p . xiv

[27] Speaking of the Chinese evacuation of the Philippines, the English historian Salmon wrote: “These islands were . . . formerly under the Emperor of China’s government, who deserted them, it seems on account of their being too remote from the rest of his dominion … . ” (Modern History. London, 1744. Vol. I, p·93. ) For other sources on China’s nominal rule over the Philippines, see Fr. Juan Gonzalez de Mendoza. The History of the Great and Mighty Kingdom of China ( London. Hakluyt Society. MDCCCLIII); Fr. Colin, Labor evangelica . (Pastells edition, Barcelona , 1900. Vol. I) ; Rafael Comenge, Los Chinos (Manila , 1894), pp. 53-54; and Laufer, op. cit., pp. 260 et seq.

[28] Vide Inazo Nitobe, Japan (London, 1931). p. 55 and Lectures on Japan ( Tokyo, Jn36) , pp. 2-6. Cf. James A. LeRoy, Philippine Life in Town and Country (New York and London , 1905), p . 21.

[29] Fr. Gaspar de San Agustin, Conquistas de las Islas Philipinas (Madrid, 169B ), pp. 260-261

[30] “Fr . Juan de la Concepcion, Historia General de Philipinas (Sampaloc, 1788- 1792) . Vol. II, pp. 32-33; Fr. San Agustin , op. cit., pp. 383-385; and Fr . Juan Ferrando, Historia de los PP. Dominicos en las Islas Filipinas y en sus misiones en China, Japon , Tung-kin y Formosa (Madrid, 1870) , Vol. I , pp. 196- 197

[31] These earthen jars were known in Japan as ” Luzon ware.” They were highly prized by t he Japanese people as receptacles for the leaves of tea. Vide Antonio de Morga, “ Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas. Mexico, 1609,” Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, Vol. XVI, p. 101.

[32] This town was called Puerto de Japon (Port of Japan) by t he early Spaniards because they found Japanese settlers and traders there. (Jitaro Kihara “Japan-Philippine Relations’ Calica. op. cit. , p .25) .

[33] G. R. Tibbetts, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 29, No. 3 (175) (August, 1956), pp., 182-208 (27 pages), Published By: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society

[34] Islas Filipinas (Madrid. 1869 ) , pp . 3-11. This work is extremely rare and the claim is made that only one copy exists today in Madrid . A typewritten copy is available through various sources online.

[35] For the study of the introduction of Islam to the Philippines, see Najeeb. M. Saleeby, Studies in Moro History, Law and Religion (Manila , 1905) and The History of Sulu (Manila, 1908 ) . Cf. Charles Livingston, “Authentic History of Sulu” , Philippine Review (Manila , April , 1916).

[36] Saleeby, The History of Sulu . p. 162.

[37] °Sharif Kabungsuwan’ wrote Dr. Saleeby, “was the son of Sharif Ali Zaimul Abidin, a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed, who emigrated from Hadramut, southern Arabia, to Juhur, Malay Peninsula.” (Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion, p. ’33.)

[38] Newson, Linda A. (2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press.

[39] “‘Had the Spaniards’ coming been delayed longer,” wrote De Morga in 1609, ”that religion Islam – Z..] would have spread throughout the islands, and even through others, and it would have been difficult to extirpate it. The mercy of God checked it in time ; for, because of its being in an early stage, it was up rooted from the islands . . . . ” (Blair and Robertson, op. Cit., Vol. XVI, pp. 134- 135 . ) Cf. Fr. Joaquin Martinez de Zuniiga. Estadismo de las Islas Filipina.“‘ (Madrid, 1893, Retana edition). Vol. II, p. 222 and Jose Montero y Vidal, Historia General de Filipina (Madrid, 1887), Vol. I, pp. 59-60. In the identical opinion of Fr. Jaime Rebullosa, Dominican historian: ,.The Mohammedans have made themselves masters of the northern part of Sumatra within these two hundred years, making use, first of commerce, then of marriage, and lastly of arms. Passing on, they have occupied the greater part of the ports of that immense Indian Archipelago; after being masters of the City of Sunda, java, they possess the greater part of the Islands of Banda and Maluco; they govern in Borneo, in Gilolo, and they had penetrated as far as Luzon, the noblest island in the Philippines, and built three towns there…and if they had not ben opposed by the Portuguese in India and Maluco, and later by the Spanish in the Philippines, and if with the Gospel their way were not checked they would doubtless now possess infinite kingdoms in the Levant” (Historia ecclesiastica, Barcelona, 1608; cited by Fr. E. Bazaco, The Church in the Philippines, March, 1937, pp. 407-409.)

[40] The early Filipino relations with Sumatra, it should be noted. were not only commercial but also cultural and political. During the heyday of the Sri-Vishaya Empire, the Hindu culture streamed to the Philippines through Sumatra. Even after the collapse of both Sri-Vishaya and Madjapahit, the Filipinos figured sporadically in the political annals of Sumatra. According to William Marsden, English historian of Sumatra, in 1539 the warriors of Luzon participated in the dynastic wars of Sumatra, and under the command of Angee Siri Timor (Rajah of Batta), they overthrew the tyrannical Alzadin, Sultan of Achin.” (History of Sumatra, London 1783. p. 346.)

[41] Pigafetta, “First Voyage Around the World,” Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, Vol. XXXIII, pp. 137-138.

[42] Blair and Robertson, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 116.

[43] Vide “Relation of the Philippine Islands. 1586,” Blair and Robertson, op. cit.,. Vol. XXIV. p. 377.

Additional Source: 1949 study “THE DAWN OF PHILIPPINE HISTORY” by Gregorio F. Zaide

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.