Before I begin, I’ll give a little bit of background as to why I am asking this question. The “Kingdom of Maharlika” was recently in the news again when President Duterte suggested reviving Marcos’ proposed name change of the Philippines to Maharlika – originally defeated in 1978 as it was seen as imperial in nature by other ethnic groups. The controversy occurs when some adhere to the belief that there was once indeed a Kingdom of Maharlika, while others refute the claim based on lack of, or false, evidence. I was recently caught in a discussion about this – which included the one true pre-colonial God – and it was suggested that Jesuit and Western documentation on the subject should be thrown out when examining it. It was also suggested that because I am not Filipino, I couldn’t understand. I am always open to learning and I by no means think I am an authority on either subject, so I am posting what I have learned about this and hoping others can share some insight from both sides. What I am hoping to avoid is what invariably turns into insults and name-calling.

I will also acknowledge that belief in the Kingdom of Maharlika and a pre-colonial one true God do not need to go hand in hand, but it has been suggested several times to me that they do.

Please feel free to message me privately – through Facebook or email. The public forum is not always friendly and I want everyone to feel safe expressing their beliefs.

When defending the popular opinion, few dismiss the authority of documentation (Spanish or American). The Maharlikan side tends to dismiss the ‘authority’ of the educational community. People don’t argue back by claiming divine authority on this topic – a popular stand in the Philippines. They argue back by claiming to have the truer indigenous authority. It can make matters incredibly confusing.

So as suggested by Alex Espinosa (conversation above), I’ve conducted my own research, and have been logical about it.

The Word Maharlika

Documented evidence shows that Maharlika is a cognate of the Malay word Merdeka (“freedom”). Both are derived from Sanskrit maharddhika (महर्द्धिक) meaning “[a man of] great wealth/power/influence”. This was not the highest estate of the Tagalog class structure – the Maginoo were.

William Henry Scott was a historian of the Gran Cordillera Central and Prehispanic Philippines. In his book Barangay, Scott explains “The word maharlika is ultimately derived from Sanskrit maharddhika, a man of wealth, wisdom, or competence, which in precolonial Java meant members of religious orders exempt from tribute or taxation. In the sixteenth-century Philippines, they were apparently a kind of lower aristocracy who rendered military service to their lords. The maharlika accompanied their captain abroad, armed at their own expense, whenever he called and wherever he went, rowed his boat not as galley slaves but as comrades- at-arms, and received their share of the spoils afterwards.

Plasencia is the only sixteenth-century observer known to mention the maharlika, and he did not explain the origin of their status. They may well have been a sort of diluted maginoo blood, perhaps the descendants of mixed marriages between a ruling line and one out of power, or scions of a conquered line which struck this bargain to retain some of its privileges. At any event, they were subject to the same requirements of seasonal and extraordinary community labor as everybody else in the barangay. Technically, they were less free than the ordinary timawa since, if they wanted to transfer their allegiance once they were married, they had to host a public feast and pay their datu from 6 to 18 pesos in gold—“otherwise,” Father Plasencia (1589a, 25) added, “it could be an occasion for war.”

This maharlika profession was destined to disappear under colonial pacification, of course, just as the raids in which it was practiced disappeared. Indeed, the effects of the change were already evident in Plasencia’s day: the lord of Pila had commuted his maharlika’s services into feudal dues. The process is reflected in seventeenth-century lexicons. Blancas de San Jose (1614a, maharlika) defined maharlika as “freemen though with a certain subjugation in that they may not leave the barangay: they are the people called villeins [la gente villano]—meaning countryfolk living on some nobleman’s villa.” But San Buenaventura (1613, 389) illustrated with the example, “Sa ikapat ang kamaharlikaan ko [I’m one-quarter free].” At the end of the century, Domingo de los Santos gave “For one who was a slave to be freed,” and in 1738 Juan Francisco de San Antonio (1738, 159) cited as a common expression, “Minahadlika ako nang panginoon ko [My master freed me].”

Tallano Claim

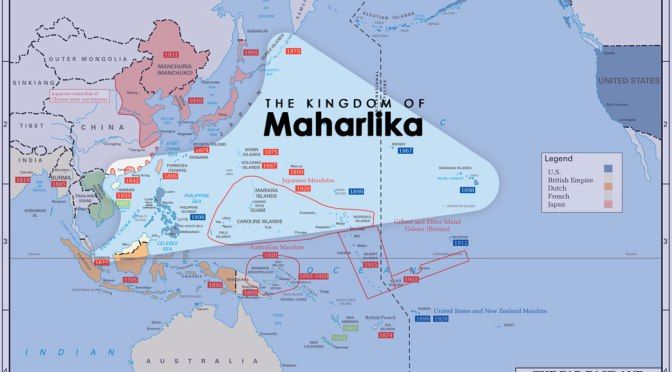

On the other side, Maharlikans claim only one royal family holds the title for the whole Philippines, Borneo, Guam, Marianas Island, Hawaii, Da Nang Vietnam, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Kuril Islands, etc.

The Land of Maharlika was composed of the Philippines, Borneo, Guam, Marianas Island, Spratley Islands and Hawaii, and was ruled by a certain King Luisong Tagean [later changed to Tallano for fear of Spanish execution].

Other territories that were said to be paying tributes to the Maharlikan Kingdom include:

- Da Nhang – Vietnam,

- Hong Kong,

- Taiwan,

- Kuril Islands

King Luisong ruled the entire kingdom from Luzon [named after him], the northern part of what is now known as The Republic of the Philippines, a registered corporate entity.

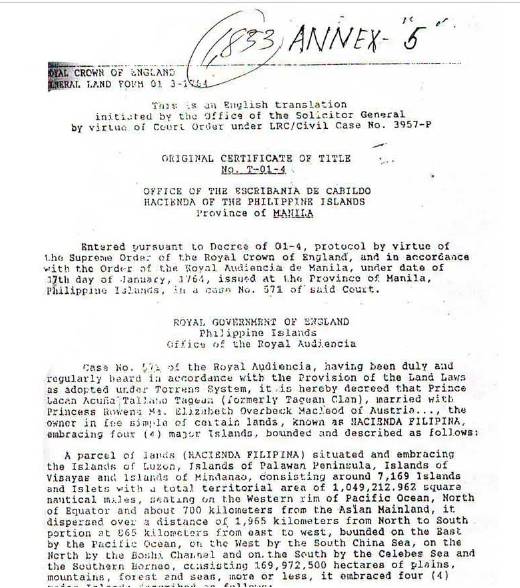

This claim was apparently supported by surveys made as early as the 9th century, purportedly acknowledged by British monarchy in the 14th century. Presented court documents, land title OCT No. T-01-4, indicate the Tagean [Tallano] Clan owns the whole Philippine archipelago, and ignored the other parts of the Maharlikan Kingdom, i.e. Sabah Borneo, Marianas Islands , Guam and Hawaii — an apparent early attempt of a major land grab by the British and other colonialists.

What To Believe?

On the one side, we have evidence that can be corroborated with the history of surrounding countries, migrations, and languages as far as the word usage in concerned. Much of these documents were written by Western chroniclers and I suppose one could claim that this conspiracy to de-power the Philippines goes back to the inception and use of the Sanskrit word, maharddhika (महर्द्धिक).

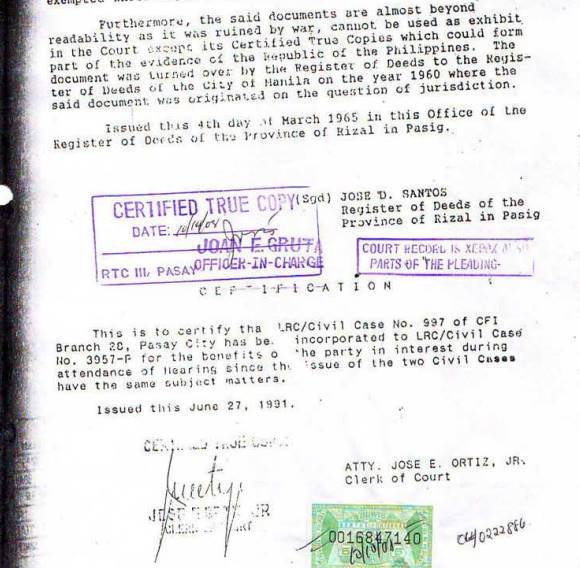

On the other side, the land title claim No. T-01-4 was issued under the authority of Royal Audencia in Manila while Manila was under control of the East India Company. It is allegedly signed by Dawsonne Drake, then governor of Manila and witnessed by His Highness, George III, King of England – this according to a translation presented during several court hearings over the years related to the Tallano estate.

In 2002 the Supreme Court of the Philippines nullified a number of bogus land titles including those from the Tallano and Acop groups. As recently as June 2017, a National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) probe requested by the DAR regarding a case in the Compostella Valley involving the Tallano group found it had no rightful claim. “Based on the investigation conducted by the NBI, the land titles of Tallanos’ group are fakes as verified by the Register of Deeds. We also found out that their leader, Tallano, is included in the list of professional squatters and a member of a squatting syndicate,” said local DAR Sheriff Adelaido Caminade. Back in 2009 the Philippine Court of Appeals invalidated a number of documents produce be those connected with the Tallano claim. As argued by Maharlikans, this could all be part of the landgrabbing conspiracy by current corporate and family powers in the Philippines, so let’s focus on the document itself.

A point that can be argued either way was well stated by blogger Bob Couttie, “Can I trust lawyers to establish the authenticity of a document in the absence of a forensic document examiner’s report and an analysis by a historian. I have a reason for not doing so: Until the mid-1990s or so, one outright fraud, the Code of Kalatiaw, produced by a known fraudster called Jose E Marco, and a document misrepresented as the early evidence of pre-hispanic treaties were required studies in Philippine law schools.

For decades not a single law student or professor had noticed, for instance, that a fort mentioned in the Code of Kalantiaw post-dated the supposed provenance of the code. Not one had noticed that the Maragtas was not based on ancient documents – the original publication says that those documents were not readable.

That being the case, I do not regard the dismissal of the OCT/Protocol 01-4 as in any way evidential without a report from a forensic document examiner and a historian familiar with the period. Since the document has not been made available for such examination it is unwise to draw any conclusion from a mere legal case.“

OCT 01-4

A lot of the Tallano claim depends upon the OCT 01-4 documents allegedly signed by Dawsonne Drake in 1764, witnessed by George III, issued under the authority of the (Spanish) Royal Audencia in Manila. This “barely readable” document has never been presented in court, to historians, or to forensic analysts. For some reason, the Tallano’s have never even presented an image of it. All we have is a “certified true copies” of the original documents. The document itself has never been presented in any court and, for some reason, no-one has sought to have it validated by a forensic document examiner or a historian familiar with the period despite the enormous sums of money and territory involved. The cynic in me wonders how documents so damaged by war can be perfectly translated, yet not photographed. But, I will leave this up to the Maharlikans to explain.

Despite assurances of the authenticity of the translation, we will look at only the first page of the document. As a study of history (albeit documented by Westerners), I feel obligated to point out some inconsistencies in which I would love clarification.

Hacienda Filipina

Let us begin with the reference to Hacienda Filipina. Despite more than 300 years of Spanish government and reports from monks and friars, no reference to Hacienda Filipina associated with a King Luisong or a Kingdom of Maharlika appear anywhere in the Ultramar archives in Villadolid or in any Spanish era documents in the Philippines.The reference comes suddenly in one document, OCT -01-4. There are references to Hacienda Filipinas, the fiscal and financial affairs of the Spanish colony, but as of this moment, there is nothing to suggest that the nation Hacienda Filipina ever existed and no original validated documents to show that it did.

King (of) Luisong

Prince Aceh of Tondo was the man the Spanish thought ruled the whole of Luzon, until they got to Manila. Aceh is better known as Rajah Matanda, who ruled Manila along with Rajah Suleyman. Lakadula held Tondo. These three held control over the area around Manila. When Legaspi arrived in Manila he discovered Aceh was just one of several datus ruling the island. He is the only King of Luzon referred to in any Spanish documents and ruled an area around Manila. There are no also no validated pre-hispanic Chinese records to indicate such.

Royal Crown of England

The British monarch was, at that time, the king of England, Scotland and Wales. The term ‘Royal Crown of England’ is, therefore, an anachronism not in use for several centuries before the dating of the document. Although unlikely, it could be argued that Dawsonne Drake simply made a mistake or deliberately falsified the document. Drake joined the British East India Company where he held the position as the clerk. At that time, he also became the governor of White Town, Madras. Because of his faithful service and good connection, he was promoted again and again until he became a member of the Madras Council. On 2 November 1762, he assumed gubernatorial office as the first British governor after the Battle of Manila (1762). Upon his return to Madras in April 1766, he was tried by the Madras Council on criminal charges including extortion from the Chinese community and “abusing his authority to extort money from anyone who came into his power.” He was found guilty and dismissed from the Council at Fort St. George, India on 2 December 1767.

Torrens System

The document provided by Tallano claims the case was “duly and regularly heard in accordance with the Provisions of the Land Laws as adopted under Torrens System,”. The Torrens title system operates on the principle of “title by registration” (granting the high indefeasibility of a registered ownership) rather than “registration of title”. The system does away with the need for proving a chain of title (i.e. tracing title through a series of documents). The design and introduction of the Torrens system is generally attributed to Sir Robert Richard Torrens, who was born 40 years after the OCT – 01-4 document was created. The Torrens System is believed to have been adopted in 1858.

Princess Rowena Maria Elizabeth Overbeck McLeod

This name can’t be traced in any Austrian, English, Spanish, or Philippine documentation, save one – OCT -01-4. Perhaps coincidentally, the Overbeck name would later become involved in a land dispute in the same region. On 22 January 1878, the Sultanate of Sulu and a British commercial syndicate made up of Alfred Dent and Baron von Overbeck signed an agreement, which, depending on the translation used, stipulated that North Borneo was either ceded or leased to the British syndicate in return for a payment of 5,000 Malayan dollars per year.

What To Believe?

There are many other historical inaccuracies in the document – we have only looked at the first page. It would seem to leave Mahalikans in the position of believing that the entirety of Philippine, Spanish, English, and Austrian history was changed to invalidate the OCT 01-4 document. This would include the Canadian born American historian James Alexander Robertson, who translated this particular part of the 55 volumes comprising the Blair and Robertson The Philippine Islands 1493-1898. It is difficult for me to wrap my head around that, but I am leaving my mind open to rational explanations. Perhaps someone out there has a photograph of any of the original documents claimed in the “certified true copies” of the translations? If there are people who will argue whether the Earth is flat or round, I have no doubt this will be equally debated.

One True God

Again, the belief in The Kingdom of Maharlika does not necessarily go hand in hand with a pre-colonial monotheistic belief structure in the Philippines, but I wanted to address both due to previous, and my most recent, interactions on the subjects.

For the side of documentation I’ll again, I’ll defer one side to William Henry Scott who published in his work “Barangay”:

“One of the first questions Spanish explorers always asked Filipinos was what their religion was. When Magellan asked Rajah Kolambu whether they were Muslims or pagans, what they believed in, he was told that they “did not worship anything but raised their face and clasped hands to heaven, and called their god Abba” (Pigafetta 1524b, 126). This was an understandable confusion. Magellan’s interpreter was a Malay-speaking Sumatran and aba was a Malay-Arabic word for father, while in Visayan Aba! was a common expression of wonder or admiration—like “Hail! ” in the Ave Maria. Five years later, Sebastian de Puerto reported from the Surigao coast that the natives sacrificed to a god called Amito—that is, anito, the ordinary Visayan term for sacrifice or religious offering.

Father Chirino (1604, 53), on the other hand, stated that of the multitude of Filipino gods, “they make one the principal and superior of all, whom the Tagalogs called Bathala Mei-Capal, which means the creator god or maker, and the Bisayans, Laon, which denotes antiquity.” The Tagalog Bathala was well known in Chirino’s day, but he was the first to mention a Visayan equivalent, and his statement was repeated verbatim by Jesuits of the next generation such as Diego de Bobdilla and Francisco Colin. But not by Father Alcina: rather, he devoted one whole chapter to the thesis that Malaon was simply one of many names which Visayans applied to the True Godhead of which they had some hazy knowledge. Thus he equated Malaon—whom the Samarenos thought was a female—with the Ancient of Days, Makapatag (to level or seize) with the Old Testament God of Vengeance, and Makaobus (to finish) with the Alpha and Omega, attributing these coincidences to some long-forgotten contact with Jews in China or India.

Raom (Laon) appears as a Bohol idol in the Jesuit annual letter of 1609, but none of Chirino’s contemporaries mentioned a creator god by this or any other name, least of all when recording origin myths. Neither did the early dictionaries. Laon was not said of persons but of things: it meant aged or dried out like root crops or grain left from last year’ s harvest, or a barren domestic animal. But Manlaon appears as the name of a mountain peak. Thus Laon may well have been the goddess of Mount Canlaon in Negros— Loarca’s Lalahon—but it is unlikely that the Visayans had a supreme deity by that name.”

On the other side, some believe the Philippines has known godliness since time immemorial. Although their history is full of depreciation by other nations, the enigma of the Philippines as a towering figure of Christianity in the orient was not affected. In Pedro M. Paterno’s opinion (1887), and further to Father Alcina’s opinion mentioned above, the Philippines got its Christian principle from the men who were in contact with St. Thomas in his missionary work in the East. Followers of this theory believe that the Christian principle was ahead of Philippine Christianization. Christianity in Asia has its roots in the very inception of Christianity, which originated from the life and teachings of Jesus in 1st century Roman Palestine. Christianity then spread through the missionary work of his apostles, first in the Levant and taking roots in the major cities such as Jerusalem and Antioch. According to tradition, further eastward expansion occurred via the preaching of Thomas the Apostle, who established Christianity in the Parthian Empire (Iran) and India. The very First Ecumenical Council was held in the city of Nicaea in Asia Minor (325). The first Caucasus nations to adopt Christianity as a state religion were Armenia in 301 and Georgia in 327. By the 4th century, Christianity became the dominant religion in all Asian provinces of the Eastern Roman Empire. Believers hold firm that the creator deities in the Philippine Pantheons should be referred to as the native interpretations of the one true God.

In other words, Paganism therefore referred to all religion which adored a false god. Paganism did not refer to Judaism nor Mohammedanism as these religions believed in their “true” God. Treading in this vein of reasoning, the Philippine ancestral religion was not pagan because it adored what it believed to be a real God, they called Bathala or Maycapal (or any other name). It is believed the current polytheistic pantheons are due to negative authors.

What To Believe?

I can’t operate The Aswang Project site and say I don’t lean towards the Philippines having had multiple polytheistic belief structures at the time of colonization. But I also won’t tell others how they should view the creator deities that exist within those structures. To believe there was a pre-colonial one true God would essentially be in contradiction of everything we know about the evolution of religion, migration and trade in SE Asia. It’s not to say these things are impossible, but it might take more than Paterno’s opinion for me to abandon fair, modern, and objective interpretations of documented history. What should you believe? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ That’s not my place to say, nor the purpose of this site. Again, I’d like to invite anyone to share opinions or knowledge on this topic. Please be respectful so we can help each other learn.

SOURCES:

Blair and Robertson’s “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898”

Tallano documents

pre-Spanish Philippines, Juana Jimenez Pelmoka PhD, 1996

Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society ,William Henry Scott,1995, Ateneo de Manila University Press

Interrogating Tallano – Is the Philippines the richest country in the world? Part 1-11

ALSO READ: Books and References on Philippine Mythology and Folklore

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.