|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What is an aswang? This is a question that has continually resurfaced during my twenty years of studying the folklore and religious beliefs of the various ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines. It is a question that so intrigued me, I spent almost five years exclusively exploring the topic, culminating in my documentary The Aswang Phenomenon (2011). It is a question that has confronted many before me, and will hopefully continue to intrigue academic and creative minds into the future. For the Filipino, the answer may seem very simple and concise. They will likely answer the question based on the belief in their community with such certainty and vigor that there is little room for misinterpretation. Moving to the next barangay will elicit a different yet equally assertive answer. Travelling throughout the country leaves one with hundreds of interpretations. This has led to the common explanation that the aswang is an umbrella term for various shape-shifting evil creatures in Filipino folklore, such as vampires, ghouls, witches, viscera suckers, and transforming human-beast hybrids. It is correct in the notion that each community holds their own interpretation of the aswang, but discounts the unique history and evolution within the ethnolinguistic group that tell the tales.

This amorphous nature is what has made the aswang such an incredible tool for storytelling. With one word to describe so many attributes for a myriad of beings, it makes for the perfect villain. Nobody exploited this better than Peque Gallaga and Lore Reyes, whether they presented a self segmenting Manananggal or a clan of cannibals in the Shake Rattle & Roll movie franchise, a shape shifting witch in Aswang (1992), or a village of ghoul-like creatures in Sa Piling ng Aswang (1999). In recent years we’ve seen new aspects of the lore in The Aswang Chronicles by Erik Matti, showcasing a rabid pack of Tik-Tik and introducing many people to the obscure aswang folklore of the Kubot. Creatives from the capital city of Manila tend to make the aswang belong to a crime syndicate, or at least heavily involved in the seedy underworld. This is most popularly seen in the Budjette Tan and Kajo Baldisimo comic and Netflix series, Trese. It was precisely this creative freedom that first led me to become interested in the aswang – ultimately becoming my “aswang project.”

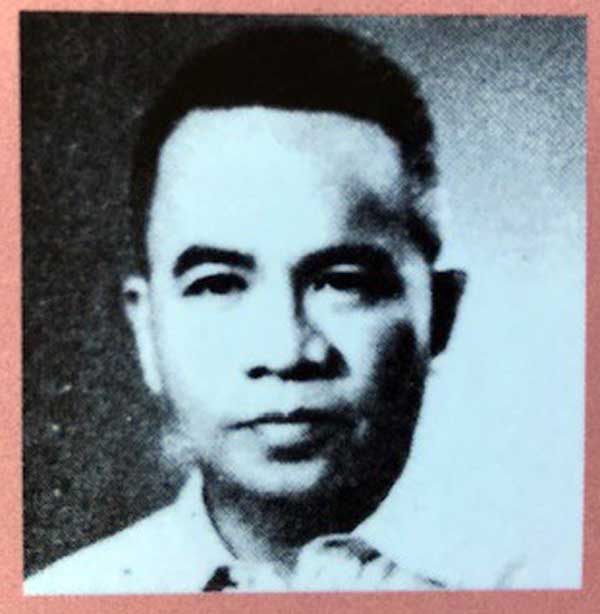

Dr. Maximo Ramos

In the 1960s, Dr. Maximo Ramos, affectionately referred to as the “Dean of Philippine Lower Mythology,” undertook the monumental task of creating taxonomical classification of folkloric beings throughout the Philippines. The culmination of this work was eventually published in a book called The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology. Within its pages, folkloric creatures are neatly placed into twelve categories; Demons, Dragons, Dwarves, Elves, Ghouls, Giants, Merfolk, Ogres, Vampires, Viscera Suckers, Were beasts, and Witches. What I found curious was that the aswang appeared in five of these categories; Ghouls, Vampires, Viscera Suckers, Were beasts, and Witches. These became the taxonomic classification for the aswang in Ramos’ later work The Aswang Complex in Philippine Folklore. These classifications have been the touchstone for movies, comics, and fiction. Without Maximo Ramos, many of these beliefs may have disappeared with time, so I must first commend his work before noting the problem it created when dealing with the aswang.

Ramos, like me, quickly discovered that to effectively answer the question of what an aswang is, one must first map the beliefs in folkloric spirits of the entire Philippines. It was this venture into unexplored territory that encouraged people to look at Philippine folklore and mythology as a serious subject and of cultural value. It was through the fieldwork of Ramos and his students that we are able to do comparative studies and trace the stories and influences brought to specific areas.

The Maximo Ramos Taxonomical Classifications of the Aswang

According to Maximo Ramos, the aswang concept is most usefully understood as a congeries of beliefs about five types of mythical beings identifiable with certain creatures of the European tradition: (1) the blood-sucking vampire, (2) the self-segmenting viscera sucker, (3) the man-eating weredog, (4) the vindictive or evil-eye witch, and (5) the carrion-eating ghoul. Thus when Philippine folk speak of the aswang, they generally refer to the physical traits, habitat, or activities of these five types of mythical beings, and sometimes also of other mythical entities like the demon, dwarf, and elf. What follows is a brief description of each aspect of the aswang, a term chiefly used by the Tagalogs, Bikol, and Visayan groups in the country.

(Blood sucker Aspect: Bicol, Cebu, Visayas, Ilokano) By Philippine folk traditions, the vampire is a bloodsucking creature disguised as a beautiful maiden. It marries an unsuspecting youth and thus can sip a little of his blood each night till he dies of anemia, whereupon the monster gets itself another husband. To suck blood the vampire uses the tip of its tongue, pointed like the proboscis of a mosquito, to pierce the jugular vein.

Instagram: @kolokomiks

Web: https://www.artstation.com/koloart

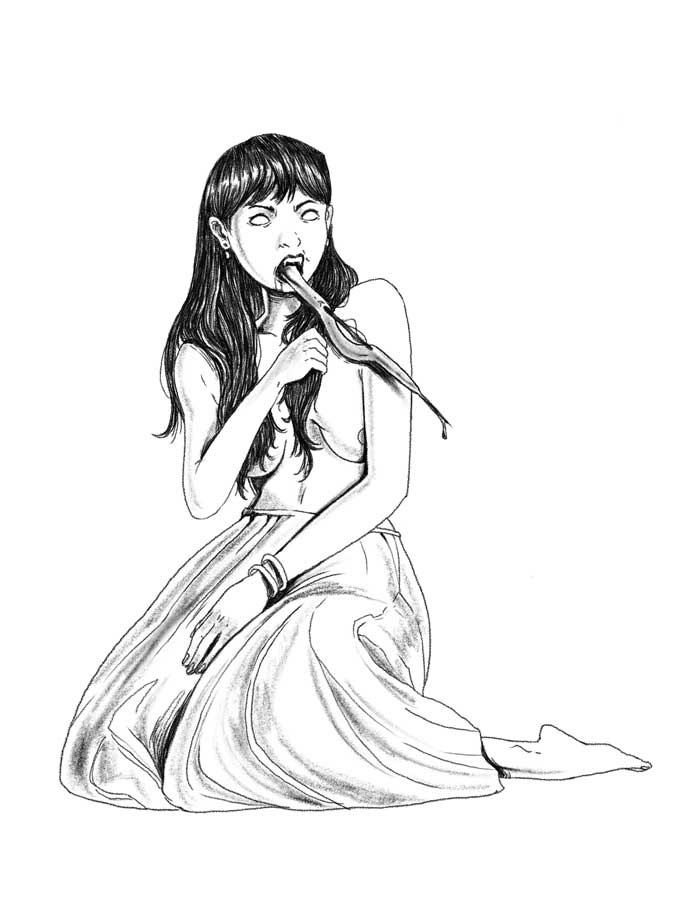

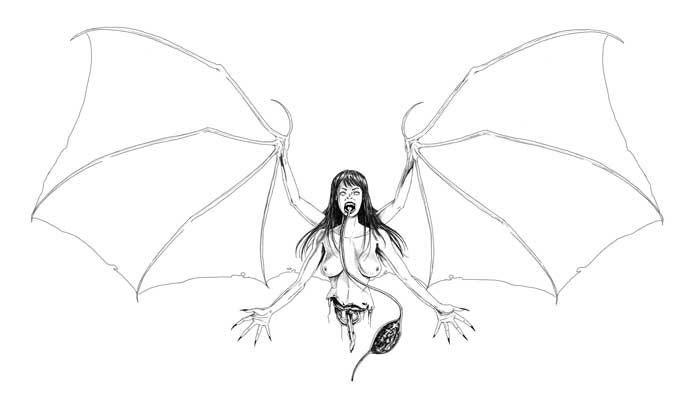

(Viscera Sucker Aspect: Bicol, Luzon, Western Visayas) The viscera sucker is a mythical being said to suck out the internal organs (naguneg in Iloko, laman luob in Tagalog, kasudlan in West Visayan) or to feed on the voided phlegm of the sick. This creature rarely occurs in European folklore but is widespread in Malaysia. It is reported to look like an attractive woman by day, buxom, long-haired, and light complexioned. Its tongue is extended, narrow, and tubular like a drinking straw — but not pointed like the vampire’s— and it is capable of being distended to a great length. At night the monster discards its lower body from the waist down and flies or floats or glides out.

Instagram: @kolokomiks

Web: https://www.artstation.com/koloart

(Were-Beast Aspects: Bicol, Cebu, Western Visayas, Luzon) The weredog is a mythical being said to be a man or woman— chiefly the former—by day, but at night to turn into a ferocious beast, principally a dog, known as aso in many Philippine languages. A werewolf is identified with the fiercest animal in a region, so that Europe has werewolves, China werefoxes, and India weretigers. Since there are no wolves in the Philippines, the term weredog is more appropriate; although the term werebeast may, in some cases, be even more applicable.

A weredog is said to reside in a village and turn into a ferocious dog, boar, or large cat at about midnight.

Instagram: @kolokomiks

Web: https://www.artstation.com/koloart

(Witch Aspects: Bicol, Cebu, Eastern Visayas) Another member of the cluster of mythical concepts encompassed by the term aswang is the witch, believed by the folk to be a man or woman—mostly the latter— who is extremely vindictive or who causes sickness without meaning to do so. By magically intruding various objects—shells, bone, unhusked rice, fish, and insects of various species—through the victim’s bodily orifices or by herself entering the victim’s body, the Philippine witch punishes those by whom she has been put out. Or by an innocent look or remark, she also makes an equally innocent victim ill. Unlike the European witches, however, the Philippine witch has no appetite for human flesh. She is shy and lives in abandoned houses at the outskirts of towns and villages. She will not look people straight in the eye because the image in the pupils of her eyes is said to be upside down and the pupils are thin and elongated like a cat’s or lizard’s in bright sunshine.

Instagram: @kolokomiks

Web: https://www.artstation.com/koloart

(Ghoul Aspect: Many areas in the Philippines) The Philippine ghoul is said to steal human corpses and devour them. For this purpose, its nails are horned, curved, and sharp and its teeth pointed. Its smell and breath are fetid, and though generally invisible, the creature is said to look like a human being when it shows itself. Some ghouls live in human communities. At night they congregate in large trees near a cemetery and then descend atid exhume the newly buried corpses. They devour their plunder, making audible noises as they do so. A ghoul is said to be able to hear, over great distances, the groans of the dying. Its greed is aroused when it catches the scent of death, and then it snatches the mourners as well as the dead.

(source: The Aswang Complex in Philippine Folklore, Maximo Ramos, 1990, Phoenix Publishing)

Instagram: @kolokomiks

Web: https://www.artstation.com/koloart

While the taxonomical classifications of Ramos assist in understanding most of the folkloric beliefs throughout the Philippines, it causes confusion when the same name is given to differing spirits from various ethnolinguistic groups. Such is the case with the aswang. It accentuates a general problem with umbrella terms used in Philippine folklore; the unique beliefs and terms among smaller ethnolinguistic groups with disappearing languages get absorbed, lost, or quite frankly hijacked by the Tagalog-centric culture that pervades popular media. Without influential and resilient oral lore and the diligent work of early Filipino folklorists, all Philippine mythological and folkloric beings may have been relegated to the Spanish terms and cognates often used to describe them in early chronicles; Bruja, Duwende, Engkanto, Higante, Sirena, Espíiritu, Demonio, and Kapre. The temptation to simplify the beliefs throughout the archipelago by using umbrella terms happened once again when the Americans arrived, and is used by Filipinos themselves when communicating in English or ‘Filipino’ as a lingua franca. There are an estimated 187 spoken languages in the Philippines, most of which have their own terms for similar folkloric spirits and creatures, so the temptation to simplify is understandable. What is fascinating about the aswang is that this umbrella term was well established by the time of Spanish arrival, as were the unique beliefs about it among the various groups. Classifying all aswang beliefs taxonomically, even with regional denotation, has given permission for creatives to mishmash elements from various ethnolinguistic groups. While still uniquely Filipino and immensely entertaining, this combining has blurred the ability to understand the evolution of the aswang and the ability to track its roots.

In future articles on The Aswang Project and in a Guide to Philippine Mythologies I am completing, I plan to build on what I learned while making The Aswang Phenomenon and in the twelve years since the documentary was released. I will share an exploration of the aswang as forms of folkloric and traditional cultural expression that continue to evolve today, and examine the earliest historical references to the aswang and the later folklorists who shaped modern understandings.

Read about more Philippine Folkloric Beasts: A Compendium of Creatures from Philippine Folklore & Mythology

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.