The early chroniclers reported that the ancient peoples of the Philippines were moved by the belief of a powerful being who was responsible for the creation of the skyworld and the earthworld and of everything in it, the moon, the stars, the trees, the animals, the springs, rivers, mountains, lakes, flowers and man himself. The name of this creator being varied with the tribes: Bathala Maykapal for the Tagalogs, Makapatag for the Bisayas, Manama for the negritoes of the eastern region of Luzon and Gugurang for the Bikols. The early Bikols regarded Gugurang to be a very good, all protecting and kindly being. He was the god of good who lived in the skyworld called Kamurawayan . On the other hand, an evil being also incessantly fought for the souls of these people. This being was the aswang, god of evil and feared by all. The aswang lived in a place called gagamban – a place of torment in the underworld.

Gugurang was the supreme god of good, benign benefactor of the village, defender of the home, who protected the tribe from the evil snares of the aswang. The general belief amongst the early Bikols was that Gugurang always listened to their supplications on matters which were for their good benefit as well as to their entreaties to protect them from their enemies. There were other kindred beings in the spirit world of the Bikols. Batala was a special being inferior in power to Gugurang whose mission was to provide peace to a village under its special care. Thus it was believed that the village that enjoyed peace and was successful in its wars was due to the influence of a Batala which Gugurang has assigned to it as its custodian. Another being inferior to Gugurang was the katambay. It had the specific mission to look after an individual as distinguished from the Batala whose mission was to care for the entire village. The hunter had a special protector called the okot. This being lived in the thick forests and whistled to indicate the place of the hunt. The fishermen, too, have their spirit protector called magindang who by its cries and signals on the water indicated the place where there is an abundant catch.

Like most of the early Filipinos, the ancient Bikols observed ritualism in diverse forms to communicate with the gods which influenced greatly their tribal and personal wellbeing. Their sense of awe and worship of the spirit world was one of obligation and commitment.

God of Good Rituals

There was a special ritual for Gugurang which was called atang. The place where the atang was usually offered was called gulanggulangan. It was made of bamboo and coconut leaves and considered the sacrificial temple of the ancient Bikols. The atang was the highest form and the most sublime sacrifice to Gugurang done as thanksgiving for a bountiful harvest and to implore for more abundant harvests. The atang consisted in offering the best of the fruits of the land which was called himoloan. The offerings were brought to the gulanggulangan and placed on an altar table made of bamboo called salangat. On it they would put many kinds of food. The native priestesses called baliana would intone the incantations followed by body shiverings and contortions. The womenfolk gathered around would then sing the soraki, reputedly a beautiful enchanting song dedicated to Gugurang. The rites over, the people consumed the food offerings in a wild dancing feast.

God of Evil Rituals

The rituals for the god of evil, the aswang, depended on the purpose for which they were invoked. The hidhid was a kind of exorcism resorted to whenever a public calamity like famine or pestilence afflicted the village. The baliana performed the hidhid ritual to exorcise the aswang believed to have brought the calamity and to force it to abandon the village in order to end the famine or the pestilence. The hidhid was also performed on a sick person believed to be under the evil spell of the aswang. The exorcism was performed by putting the leaves of the buiiga (areca nut) on the head of the sick. The baliana moved around the sick person dancing, shivering and contorting, uttering incantations against the aswang so the latter will go and abandon the sick person. If the sick was cured, they would say that the ritual was effective. However, if the sick died, it was believed that the aswang wanted to bring the sick person to the gagamban, there to suffer horrible torments. Another ritual for the aswang was the hogot. It was believed that when a datu in the village died, the aswang will seek the entrails of the deceased. To prevent this, a favorite slave of the datu was killed and his entrails were offered to the aswang as substitute.

Superstitious Beliefs

They have the superstitious belief of the existence of the bonggos, an evil spirit in league with the aswang which by its order moves around in the forests. The bonggos were black and ugly beings whose eyes radiated flames of fire. They also believed in the existence of the drago or Oriol , a fabulous snake, daughter of the aswang who appears and disappears at will. Her mission is to seduce men when she wills. Her beauty and influence were irresistible. A thousand fables were said about this snake-enchantress. Another evil spirit is the yasao whom the early Bikols regarded with fear and terror. The yasao was a horrible phantasma that appears during moonlight nights, in the shadows of the trees, terrorizing the people with fear. Sometimes this evil being transforms itself into the laqui a monster with feet and hair of a goat and an ugly human face.

Belief in Afterworld

The ancient Bikols believed in an after life. The good eventually will go to the side of Gugurang to receive the reward for their heroic deeds, their achievements and exploits in war in the skyworld called kamurawayan where peace and rest await them. The bad will go to the side of the aswang in the tormenting gagamban and there suffer the punishment for their evil deeds. This belief of the early Bikols in a kamurawayan and a gagamban in the next world was higher in form to the belief of many early Filipinos who considered the transition between life and the great beyond simply as a journey beyond the seas, represented in that famous archeological soul-boat of the Manunggul burial jar, where the eternal boatman, Maguayen, ferried a dead soul on the journey to the great beyond. Although the early Bikols believed in the soul-boat symbol in much the same way as did the primitive makers of the manunggul burial jar, there was a marked difference in their beliefs because the early Bikols believed that the journey was not to the unknown but to some fixed destination of a life of reward or punishment represented by the skyworld kamurawayan and the lower world gagambam.

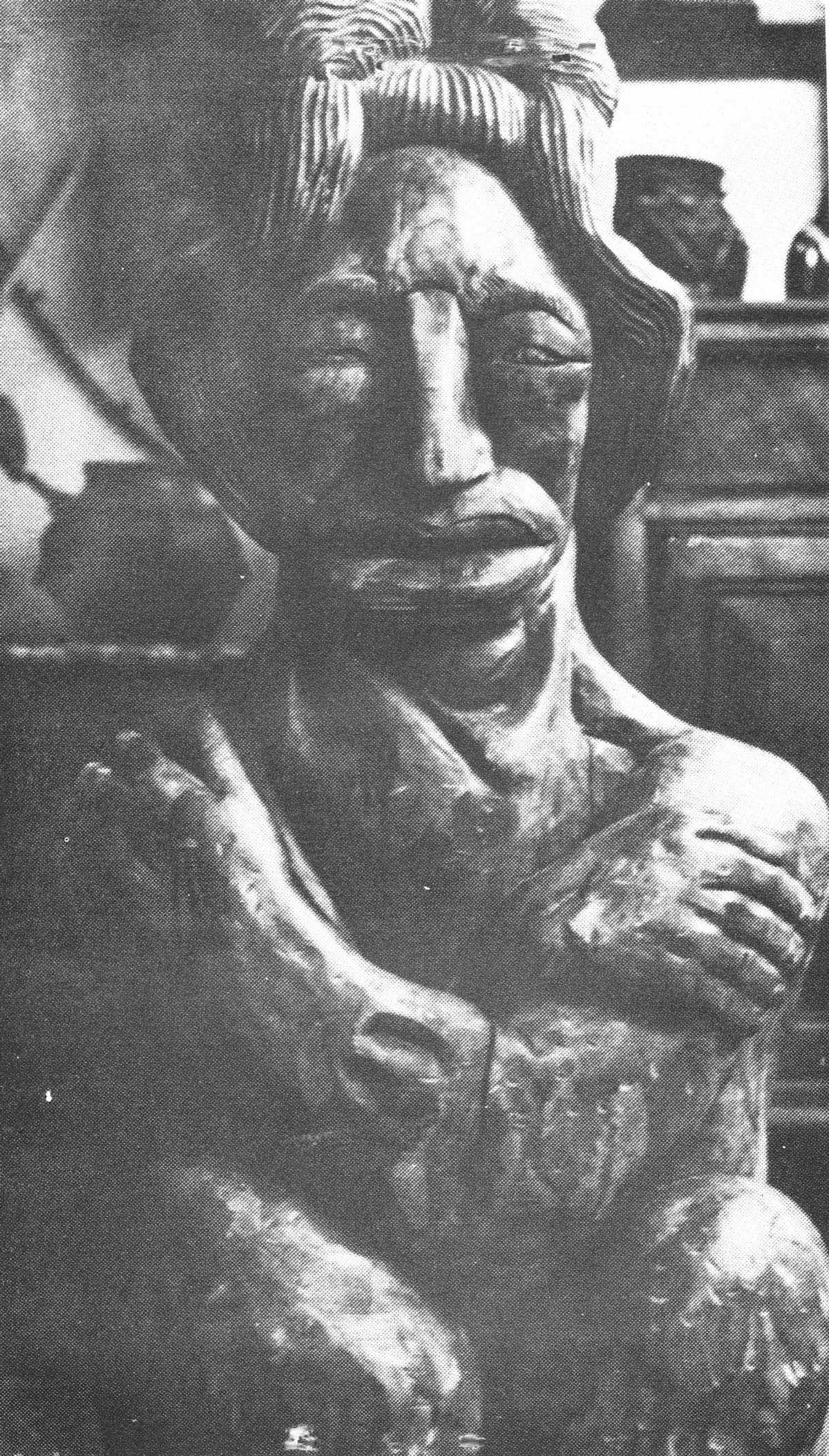

Archeological finds in Bicol grave diggings have revealed crudely carved images of stone or clay figurines of idols and deities. These are not common grave furniture. And yet, they have been found among the articles which were interred with the early Bikol dead, indicating adherence to the belief of a journey to the world which ends in the company of some deity. There are very few and scanty descriptions of these pagan idols or deities in Spanish chronicles. One was Pigafetta’s who described them as “having arms which were open, feet turned up under them and with a large face.” The early missionaries equated the devil with these pagan idols. Hence, hundreds of them were burned and destroyed before they could be described and recorded for posterity. Fray Marcelo de Rebadeniera wrote, “the natives would be asked to bring out their idols which they still believe and revere by offering perfumes and odorous scents. The natives would gather all their idols, in one case four hundred of them, and in the presence of the villagers they bum them.” It is a rare find if today some stone or clay figurine of a pagan idol is excavated approximating Pigafetta’ s description.

Cult Ministers

The ministers of the ancient Bikol religion were called asog. They wore necklaces and collars of precious stones. In his ministry, the asog used to dress as a woman and acted in the manner of a woman both in movement and in speech. Among the Suban-ons of Mindanao, a minority group separated from the Bikols by innumerable islands in a wide expanse of seas, it is noteworthy to find the term Asog in their ethno-epic as a god-deity who could resurrect the dead to life. To the ancient Bikols, however, Asog was a high priest. The ridiculousness of his appearance and his wit caused much merriment among the participants in the tribal rituals. It was the custom among the asogs to remain unmarried to prepare them better for their ministry.

There were also woman ministers called balianas. The balianas were the women of the tribe who were the most shrewd, libertine and seductive. The baliana, aside from officiating in the tribal rituals listened to the complaints of the members of the tribe and in their behalf invoked and entreated the anitos for guidance on the specific matter on hand.

Ancestor Worship

The most common of the cults of the ancient Bikols was anito worship or magaanito devoted to the spirit of deceased elders. Dr. Pardo de Tavera traced the etymology of the word anito to the sanskrit hantu which meant “death”, thence to the Javanese antu which represented spirits in general, thereby expanding the connotation of the word in its Malay concept. In the Bicol spirit world, anito became an almost filial relation that transcended death between the living and the spirit of a beloved deceased elder. The anito was regarded as the messenger or agent of the living to the overlord Gugurang. As a beloved person who in his lifetime was distinguished for his valor or goodness done to the family or to the village, now that he has journeyed to the great beyond he must still look after those he had left behind. The early Bikols believed that different kinds of anito exist, each one having a specific care function. An anito that was privately revered by a tribal household was called tagna and usually engraved in an image called lagdong and placed in a special place in their habitation called moog. This anito stood as the guardian of the home and the members of the house hold. The anito which was considered the village benefactor was called parangpan and was enshrined in a conspicuous place in the village. Its function was to protest the village in general.

A magaanito rite took place when a maguinoo died. The natives performed a ceremony for the dead called pasaka, which consisted in preserving and keeping unburied for a long time the remains of the dead, until a big feast called abataya was celebrated to extol the qualities of the deceased during his lifetime. In order that the remains will not deteriorate, they embalmed the dead in their own way – by removing the entrails. This done, the body was placed between two halves of an agul tree the inside of which had been hollowed out. The tree-coffin was then sealed with the sap of the dangkalan tree. Strangely but true, no foul odor emitted from the tree-coffin which was left unburied for sometime.

The basbas was a rite for the dead which literally meant the washing of the dead. It was the common belief that those who have died are impure, especially those who have died because of sickness and that unless purified, they would suffer great torments inflicted by the aswang. The purification rites was performed by the balianas, who fashioned at the end of a short pole the aromatic leaves of the lukban. The pole was soaked in perfumed water and struck at the various parts of the body of the deceased accompanied by the ritual song called katumba. Once the purification rites were made it was believed that the anito of the deceased journeyed freely in the valleys and the luxuriant forests of their settlements. Should a misfortune befall the village, they called upon the most celebrated of their anitos, and implore him with reverential respect by way of sighs and shouts to cast away the malaise. In order to hasten the grant of their petitions they performed the dool which was to abstain from eating foods which they usually like to eat.

They have also the child ritual called the yocod which was to offer the young child or infant to the anitos of their deceased ancestors by tossing and passing the child from one hand to another rapidly around their dwelling place. It was believed that once the aswang heard the ritual it will allow the child to come under the protection of the anitos.

Nature Cult and Rituals

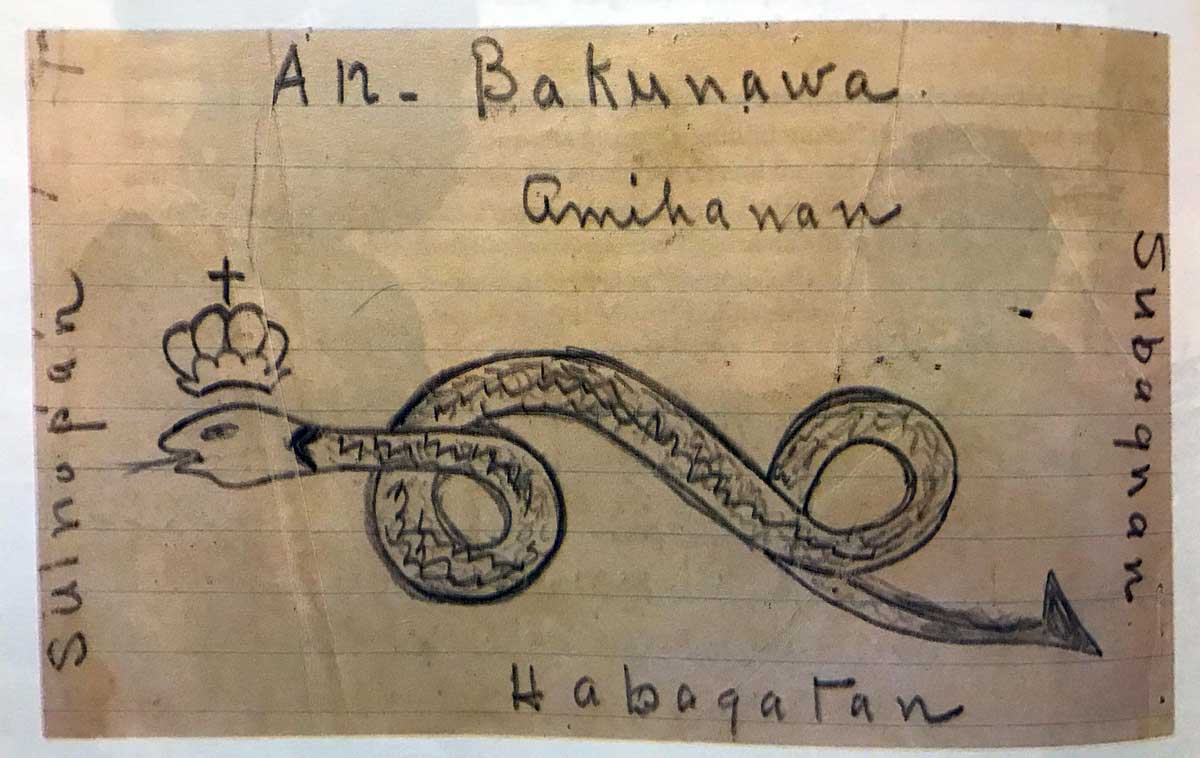

The ancient Bikols were also nature worshippers. They stood in awe and prostrated themselves in worship before the ineffable god of nature. The halia was a feast dedicated to the full moon to prevent the bakonawa, a horrible sky serpent from devouring the moon and leaving them in perpetual darkness. The feast was performed with the wild beating of the gimbals and the balalongs. The womenfolk of the tribe assembled in two files and commenced singing incantations in praise of the attributes of light of the moon they would also praise the moon in making the night as bright as day but enchantingly cooler than daylight. The early Bikols also had great reverence for the rainbow which they called hablong-dawani. They believed that it was the exquisite tapestry of a very famous weaver called Dawani who was the mother of all weavers in ancient time. It was believed that, men who braved death, those killed by arrows and crocodiles ascended directly to heaven by the rainbow.

The pre-hispanic Bikols were moved by these creator being belief and they manifested this sentiment in their cults and rituals. This metaphysical gift of primitive faith in the Bikols’ pagan soul was not destroyed nor obliterated by conquest and subjugation. many of the ancient Bikols’ belief and customs, some Bikol Christian festivals and practices today still bear a vague image of the beliefs

and customs of 400 years ago.

The Tinagba harvest festival celebrated annually in the City of Iriga on the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes which consists in offering the first best produce of the land and any product from the people’s toil is another Christian practice that is reminiscent of the atang sacrificial ritual to Gugurang. The deep devotion of the Bicolanos to the souls in purgatory is another Christian flowering of the early Bikols’ ancestor worship. The hablong-dawani, expression of ancient time is now even incorporated in a “dalit” to the Virgin of Peniafrancia which figuratively says:

“An gabos nagsasabi

ika an hablon-dawani

na an damat o’ an peste

saimong pinadadai.”

“All are saying

You are the rainbow

Sickness or pestilence

Is yours to dispel.”

The present day interest in the unconscious or the subconscious; in the occult and the hidden processes of the mind; in faith healers or arbularyo; in enkangtos, duwendes or taong lipod; in spirit exorcism or its Bikol equivalent of pag-bawi, santiguar and apag are not really new. These practices and beliefs have been with Bicolanos, as they have been with many Philippine ethnic language groups since time immemorial.

Source: Bikol Maharlika, Jose Calleja Reyes, Goodwill Trading Inc, 1992

ALSO READ:

Ancient Bicolano Pantheon Of Deities And Creatures | Philippine Mythology

HALIYA: Bicolano Goddess Of The Moon? Fact & Fiction

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.