For the northwest winds bring the feared salakap, the spirits of epidemic sickness, to earth.

The name Tagbanua derives from tiga banua, meaning “people of the village.” There is evidence of early influence from Hinduized Brunei. In more recent times, Muslim traders and aristocrats, chiefly Tausug from Sulu, dominated Palawan. Although Magellan’s expedition made a landfall on Palawan, and its chronicler Pigafetta recorded an impression of the natives, intense Spanish contact did not begin until the 1872 founding of the town of Puerta Princesa at the northern edge of Tagbanua territory. American contact with the Tagbanua only commenced with the 1904 founding of the Iwahig penal colony. Catholic and Protestant missionaries have had only limited success in converting the Tagbanua. They inhabit both the eastern and western coasts of the central portion of Palawan Island, which lies between Mindoro and Borneo.

THE SALAKEP

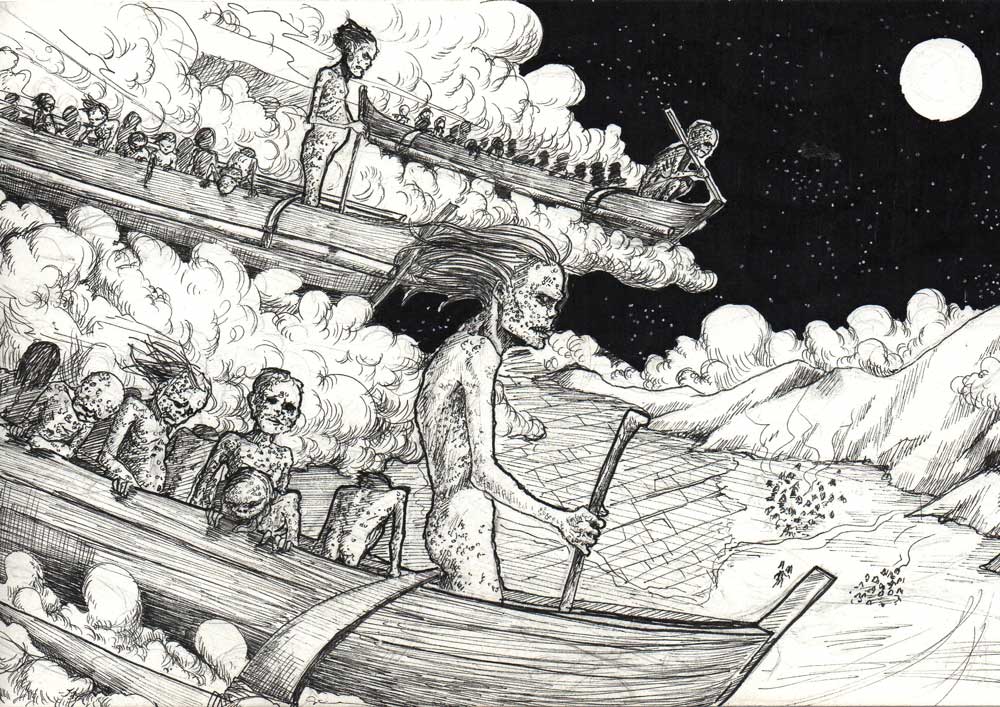

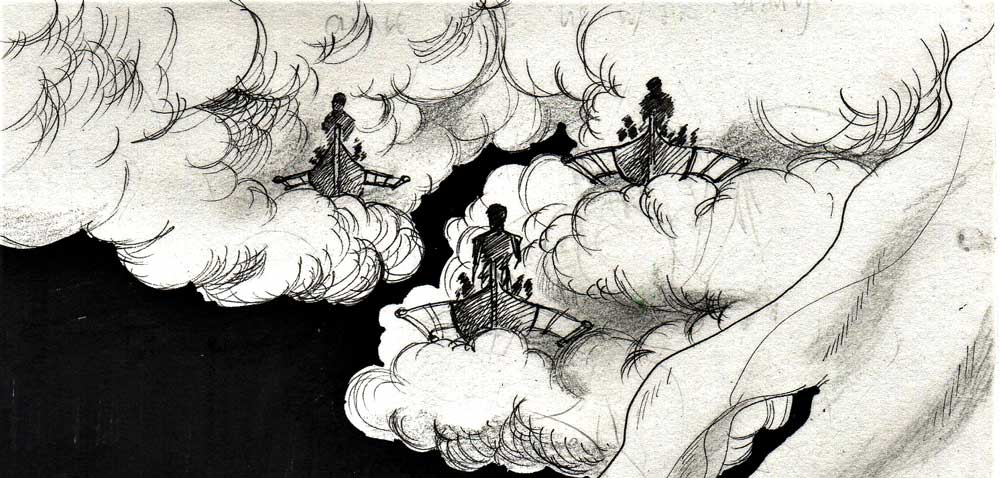

The salakap, in a huge outrigger (the adiyung), sail with northeast winds through the “high regions” and carry back to kiyabusan those who have died from panglubaw, smallpox, tai tai dysentery, tarangkaso (Sp.), “flu”, and so forth. It is said that the salakap plant a tree called daunu (not found on earth) during the time of the northeast winds. A person will become ill if he even scents the fragrance of the flowers of these trees carried with these winds. A number of deities are associated with the slakap plant, notably the tumungkuyan, tandayag, sumurutun, and the lumalayag. The tumungkuyan are said to be the leaders of the salakap. They “paint”, as has been seen, the trunks of the trees which support the sky with the blood of the epidemic-dead.

Sumurutun is the captain of the outrigger which transports the dead to kiyabusan. Numerous informants spoke of seeing this outrigger in their dreams filled with the spirits of their loved ones. Epidemics have been a terrible reality to the Taghanuwa. As late as November, 1943, after a long rainy season, an influence epidemic swept through Baraki. Limwan’s kin group and some unrelated persons fled to the Dalni branch of the Talakaygan River. Numerous rites were held but seventeen out of approximately fifty people in the group died.

The salakap are described as small, dark kinky-haired beings. Their bodies and faces are covered with pockmarks (pangkot). Doctrine concerning the salakap can be best illustrated by citing a myth:

SALAKEP MYTH: A long time ago the salakap lived with the Tagbanuwa and the two people were friendly. One day they all decided to go fishing at the seashore. It was agreed that they would go in two groups – the Tagbanuwa in one group and the salakap in the other. Now the trail to the seashore forked and it was planned that whichever group arrived at the fork in the trail first would leave some komuy (a rice preparation) wrapped in alimutyukan (Mallotus ricinoides Muell.-Arg.) leaves in the trail, in order to indicate the direction that the first group had taken.

The Tagbanuwa reached the fork in the trail first and they decided to play a trick on salakap. Instead of placing komuy in the leaves, they proceeded to the beach.

When the salakap arrived at the fork they saw the sign (patudu) had been left on the trail as agreed. They picked it up and said, “This smells good.” Then they opened the package and said that it was filled with human excrement instead of komuy. They were very hungry, however, and decided to eat it anyway. When the salakap finished, they said: “That was very good. If the waste matter of the Tagbanuwa is so tasty, their flesh must be even better. Let’s eat them all.”

Now the salakap proceeded to the beach and caught and ate all but two of the Tagbanuwa who were fishing, a man and a woman. Then they returned to the dwellings of the Tagbanuwa and devoured all of those who had remained behind. The salakap told the surviving man and woman that they were going to kiyabusan. The said that the two must promise to hold a runsay ceremony once a year – the second night of the full moon in December. If they did not do so, they would return and devour them.

The salakap sailed away in their outrigger and the people have held the runsay as promised, every year.

Two other myths were also recorded which describe the salakap and the origins of the rites which protect the Tagbanuwa against them. The variable nature of the doctrine is clearly shown. Nevertheless, each of these myths was vividly real to the person who related it.

SALAKEP MYTH: A long time ago one of the members of the family of a leading ginuu (hereditary leader) died. Now there were two young male slaves in this family and they were assigned to guard the deceased. The body was placed in a small house, the kumbu, not far from the dwelling of the family. They laid the body out on the bamboo floor of the small house. They were told that if they tried to leave they would be killed by the first person who saw them.

The two young slaves had no food or water. They had been left to starve to death. On the third day, when they were frightfully thirsty, the sagu (body fluid) of the corpse began to flow very fast through the flooring of the small house. One of the slaves said to the other: “I am going to taste this/” He did and found that it was very good. The other slave joined him and they drank the fluid.

For two more days until the sagu stopped flowing, the two young slaves lived on this fluid. On the sixth day they entered the house and fed on the flesh of the corpse. By the end of the seventh day, they had consumed all of the flesh.

At this time they talked and decided that they were no longer human but rather salakap, for they had eaten human flesh and moreover, craved for more. They agreed that they would go to kiyabusan, one to the east and the other to the west, and that every year they would return to earth to see each other and feed on the Tagbanuwa.

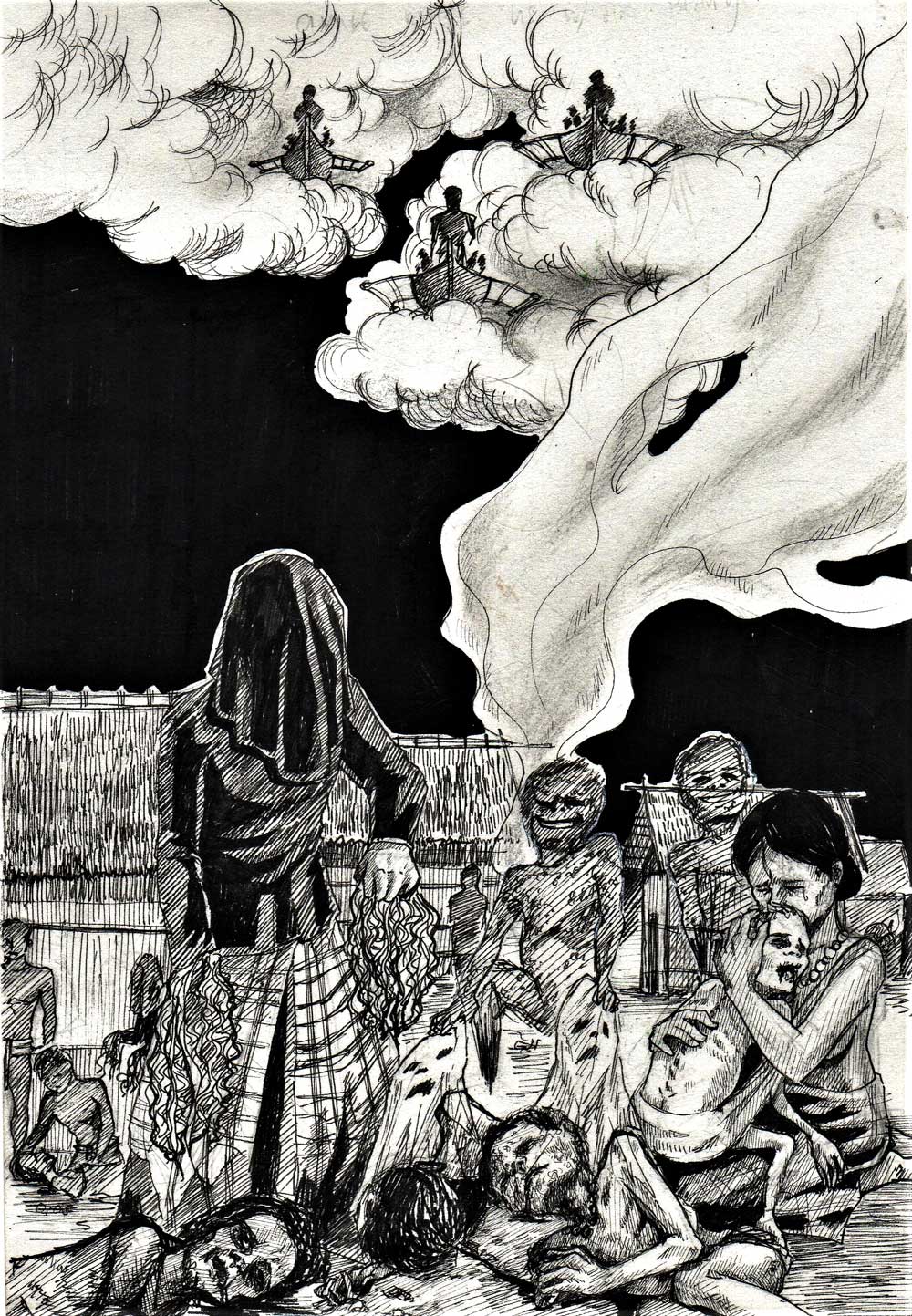

Not long afterwards a man had a dream. He was told in his dream by these two salakap that, if he prepared sweet dishes of rice, pepper, one egg, ginger, and some cleaned “new” rice, they would not eat many people. Still later other Tagbanuwa began to help this man in the preparation of the gifts for the salakap and in this way the runsay was began.

The following myth was told by Rinson of Kabigaan and like all of the myths which he related, it is highly personalized:

SALAKEP MYTH: When the salakap came and everyone was falling ill from smallpox, my grandfather (Banda) ran into the forest. During his first night in the forest he had a dream. A being came to him and asked, “Why you’re running away? What are you doing in this place?” My grandfather answered: “I am not running away. I am looking for food.” The person in his dream replied: “You are running away, I know. If you don’t want to get sick, return to your home. Meet me tomorrow morning at the mouth of the Singanang River, at the place called Ibata. We will make a blood brother pact.”

The next morning, as he was instructed in his dream, my grandfather met the “man.” It was a deity named Fuku (“Smallpox”). He was a huge man. His buttocks left an impression in the earth where he sat that measured seven hand spreads. They performed the blood brother ceremony.

The deity told my grandfather that, if he did not want to become sick and if he did not want his relatives to become sick, he must perform the bayis ceremony every year and call him. The diwata (deity) told my grandfather exactly how to perform the bayis.

IG: @famskaartyhan

FB: @famskaartyhan

These myths illustrate the often subtle relationships between beliefs and everyday modes of expression. The concept of death is expressed in a number of ways. There are those who simply “die,” patay of natural causes in the sense that we use the term “die.” These dead go to basad, the underworld. Some people are killed by violence and “poison.” They are bangkay and inhabit the “high regions.” The deaths, on the contrary, of the babalayan and the “priests” or “priestesses” are due to the “will” of the highest ranking deity. Unique rites and mortuary practices, such as secondary jar-burial, were associated in the past with the deaths of important religious functionaries. Finally, the Tagbanuwa can be “eaten,” kumaan, and the term is used by them with this literal meaning. They are eaten by the salakap and, as will be seen, by a number of evil spirits who inhabit the immediate environment. The expression “being eaten” might also be correlated with the consequences of the corpse-exposure and secondary jar-burials. This idiom is vividly stated, at any rate, in many of the Tagbanuwa’s myths.

The Tagbanuwa do think they are entirely at the mercy of the salakap, for the lumalayag or “sailors”, as well as a deity called tandayag, also live in kiyabusan. Tandayag, it is said, was sent by the highest ranking deity to live with the salakap in order to prevent them from sailing except during the northeast winds. He has no control over them during this period, as there is an agreement between the highest ranking deity and the salakap that they can sail with the northeast winds.

There is unquestionably a relationship, as expressed in Tagbanuwa myth and belief, between the intensity of sickness and the period of the year in which the northeast winds blow. This is the period roughly beginning in November and continuing into January. It follows the months of heaviest rains during which the Tagbanuwa are cold and wet. It is the season when the Tagbanuwa have regrouped in their permanent villages and when there is intensified social interaction at rituals and drinkfests. The recent instances of epidemics have all occurred, in fact, during the northeast monsoons.

The lumalayag are spoken of as “warriors” who challenge and fight the salakap. One informant remarked: “They cannot be stopped by the salakap. They are like prophylactics. The role of the “sailors” is dramatically expressed during the diwata ceremonies. Helpers of the babalyan pop repeatedly the timbak timbak to simulate a fireweapon. These are bamboo tubes in which plugs made from the pith of the banana stalk are inserted and then struck with a mallet. They make quite a bang. At the same time the babalyan increases the tempo of her dance wearing a kris (Moro fighting weapon) in her waist sash and carrying a miniature spear and shield in her hand. These actions mirror the attack by the “sailors” upon the lustful deities of epidemic sickness.

SOURCE:

FOX, ROBERT B. Religion and Society Among the Tagbanuas of Palawan Island, Philippines. Monograph No. 9, National Museum: Manila, 1982.

ALSO READ: Tagbanua (Tagbanuwa) Cosmology: Multi-Layered Universe, Deities, Diwatas and Creation Myths

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.