The child deity Santonilyo is considered the “god of graces” within the ancient Visayan pantheon. It has always fascinated me, not just because of it’s obvious similarities to the Christian image of Santo Niño, but because of its interconnection with recorded historical fact. It is through these recordings of history that we are able to piece together speculative glimpses of the societal past. In the case of Santonilyo, the evidence leads us on a fairly distinct pathway towards its origins, but leaves open the influence Catholicism had on pagan beliefs. In fact, it is more a study on how pagan beliefs influenced Catholicism in the Philippines.

Magellan’s gift of the Santo Niño

In April 1521, Ferdinand Magellan, in the service of Charles V of Spain, arrived in Cebu during his voyage to find a westward route to the Indies. He persuaded Rajah Humabon of Cebu and his chief consort Humamay, to pledge their allegiance to Spain. They were then baptized into the Catholic faith, taking the Christian names Carlos (after Charles V) and Juana (after Joanna of Castile, Charles’ mother).

According to Antonio Pigafetta, Italian chronicler to the Spanish expedition, Magellan handed Pigafetta the Santo Niño image to be given to the newly-christened Queen Juana right after the baptism.

“The captain on that occasion approved of the gift which I had made to the queen of the image of the Infant Jesus, and recommended her to put it in the place of her idols, because it was a remembrancer of the Son of God. She promised to do all this, and to keep it with, much care.” ~Pigafetta

Rediscovering the Sto. Niño

On April 27, 1565, (44 years after Magellan) Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in Cebu. He found the natives hostile and fearing retribution for Magellan’s death. The village was burned during the ensuing conflict. Spanish mariner Juan Camus found the image of the Santo Niño in a pine box amidst the ruins of a burnt house. The image, carved from wood and coated with paint, stood 30 centimeters tall and wore a loose velvet garment, a gilded neck chain, and a red woolen hood. A golden globus cruciger or orb was in the left hand, with the right hand slightly raised in benediction.

Camus presented the image to Legazpi and the Augustinian priests; the natives refused to associate it with the gift of Magellan, claiming it had existed there since ancient times.

The aforementioned fear was the likely motivating factor for this, but the Santo Niño may also have taken on mythical status by this time. Additionally, perhaps good fortune actually did coincide with Santonilyo being brought out for successful harvests, bringing rains, or catching bounty from the sea.

Legend of the Santonilyo Agipo (driftwood)

It is told, long before the coming of the Spaniards, a native went out to sea. He could not catch any fish the whole day long. Finally, he felt a weight in his net. He brought it in, only to discover that it was nothing but a piece of agipo (driftwood). Cursing, he threw it back into the sea. Soon after, he felt another tug in his line but, again when he brought it in, it was the same piece of wood. Over and over he would catch the agipo and then dump it back into the sea only to catch it again. Finally tired and angry, he decided to keep the driftwood in his boat. Like magic, all the fish in the sea flocked towards his boat and he returned to his village with a bountiful catch.

The natives of Cebu soon discovered that this piece of wood had other magical powers. They could use it as a scarecrow to keep the birds and animals away from drying grains. In times of drought they only had to immerse it in the sea and the rains would come. It was then that this agipo became an idol in their pantheon, a god of graces.

A possible explanation has been hypothesized that the image of the Sto. Niño may have been introduced through traders from China. The theory branches into speculation when it suggests that a Chinese artisan may have reproduced the images brought from Franciscans who visited during, and after the time of Marco Polo (late 13th Century/ Early 14th). Somehow this image made its way to Cebu. There is no disputing there were Chinese Traders, but existing documented evidence of the Santo Niño paints a much clearer picture.

The cooperative nature of the natives and the discovery of the Sto. Niño ultimately worked to the benefit of the village – especially in comparison to the other areas of the region who were forced to pay tribute to the newly established Spanish government.

Miguel de Loarca wrote, “On the other side of the above-mentioned native communities, at about two arquebus-shots from the Spanish town of Santisimo Nombre de Jesus (thus called because an image of the child Jesus, of the time of Magallanes, had been found there, and was held in great reverence by the Indians), is a village of the natives belonging to the royal crown, with about eight hundred Indians. The commander Miguel Lopez de Legazpi exempted this community from paying tribute; for they had always taken sides with the Spaniards, and had helped them to conquer some of the other islands.”

~Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas; [Arevalo, June 1582)

Santonilyo, God of Graces

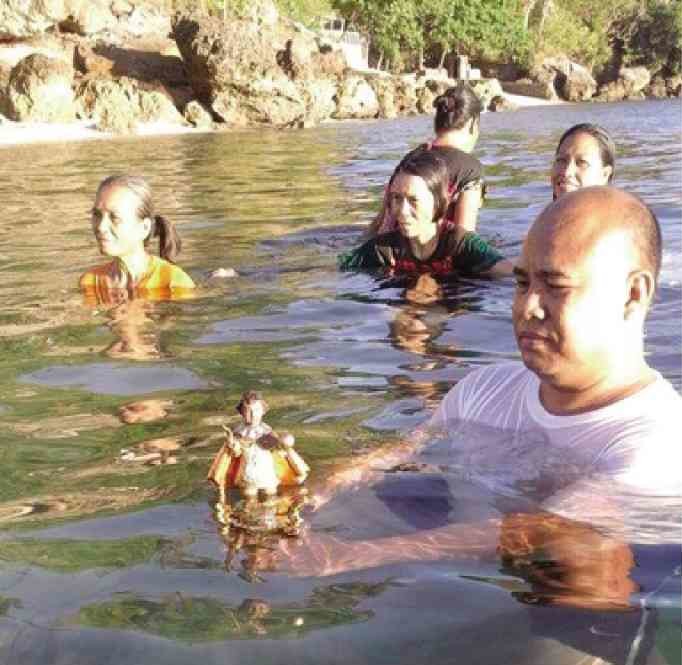

Soon after Magellan’s demise, it is believed the practice of bathing the image of the Sto. Niño in the sea during droughts began. It was told that the natives had only to immerse the icon in the sea and the rains would come. At that time, the ancient Cebuanos would use the original image of the child Jesus that was given by Magellan as a baptismal gift. Fray Gaspar de San Agustin wrote about it in his book “Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565-1615)”.

The practice of immersing the sacred image is also mentioned in the Sto. Niño’s Gozos, or prayer hymn, published in an 1888 novena.

“Cun ulan ang pangayoon ug Imong pagadugayon, dad-on Ca sa baybayon ug sa dagat pasalomon, ug dayon nila macuha ang ulan nga guitinguha,”

(If they seek rain and You delay it, You will be brought to the shore, and bathed in the sea. And they then obtain the rain they desire.)

The Santonilyo Legacy

The pagan legacy of Santonilyo is on full display in Cebu. Santo Niño was popularly considered the official patron of Cebu – much like Santonilyo was the idol and deity of graces before the mass conversions to Catholicism. So strong is this notion, the Church in the Philippines needed to suppress it and clarify that it is not the representation of a saint that intercedes to God but rather of God himself (specifically, Jesus Christ).

Regardless, the vendors outside of Cebu’s Basilica del Santo Niño will readily tell you that the Sto. Niño is a patron and will bring good fortune.

It remains a fairly indelible fact that Santonilyo was spawned from the image of Sto. Niño, but I would argue that the popularity of the Sto. Niño in Cebu owes itself to Santonilyo.

H. Otley Beyer once said of the Philippine flood myths, “I see no good reason why the story should not also be [seen as] a native development in spite of its similarity to the Hebrew myth.”

Similarly, I see no good reason why the appropriation of Sto. Niño into Santonilyo should be seen as anything other than a Native development, and a welcomed member of the Visayan pantheon of deities.

ALSO READ: Ancient Visayan Deities in Philippine Mythology

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.