I wanted to write an article on this particular deity because there seems to exist the idea that Sitan could only come from the Christian concept of Satan. While there is some truth to this, it came in a much more roundabout way. In this article I will present why I believe the name sitan, associated to the ’embodiment of evil’, existed in Tagalog beliefs before the arrival of Catholicism.

SITAN: Deity of Kasanaan?

In Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano wrote, “The ancient Tagalogs also believed in the final judgment of men—that is, the punishing of the evil and the rewarding of the good. The souls of good men were said to be taken to a village of rest called Maca, which resembled the Christian Paradise, where they enjoyed eternal peace and happiness. However, those who deserved punishment were brought to Kasanaan, the village of grief and affliction where they were tortured forever. These souls were kept there by the chief deity named Sitan.”

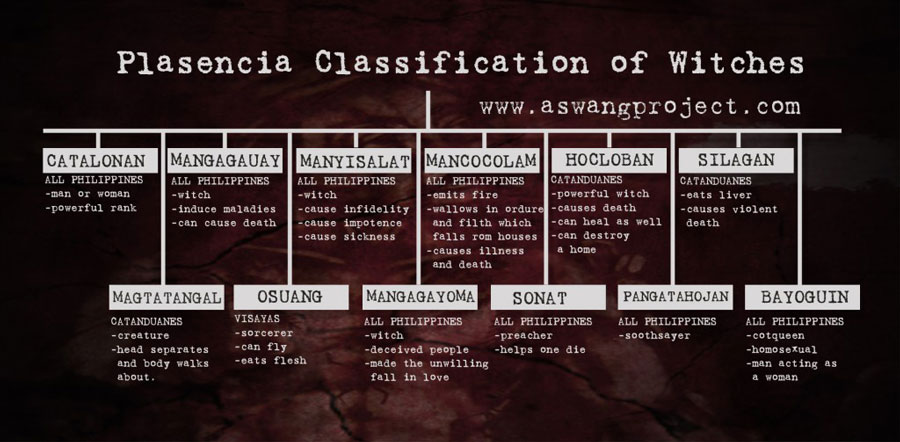

Modern presentations on Tagalog beliefs present that Sitan was assisted by many mortal agents. The most wicked among them was Mangagauay. She was the one responsible for the occurrence of disease. She was said to possess a necklace of skulls, and her girdle was made up of several severed human hands and feet. Sometimes, she would change herself into a human being and roam about the countryside as a healer. She could induce maladies with her charms.

If she wished to kill someone, she did so by her magic wand. She could also prolong death, even for a number of months, by simply binding to the waist of her patient a live serpent which was believed to be her real self or at least her substance.

The second agent of Sitan was called Manisilat. She was sometimes known as the goddess of broken homes. She was said to be restless and mad whenever there was a happy home within sight. And when she was determined to destroy every such happy home, she would disguise as a woman healer or an old beggar, enter the dwelling of her unsuspecting victims, and then proceed with her diabolical aims. With the aid of her charms and magic powers, she would turn the husband and wife against each other. She was most happy when the couple quarreled and she would dance in glee when one of them would leave the conjugal home.

The third agent of Sitan was known as Mankukulam, whose duty was to emit fire at night, especially when the night was dark and the weather was not good. Like his fellow agents, he often assumed human form and went around the villages pretending to be a priest-doctor. Then he would wallow in the filth beneath the house of his victim and emit fire. If the fire was extinguished immediately, the victim would die.

The fourth such agent was called Hukloban. She had the power to change herself into any form she desired. In fact, some people said that she had greater power than Mangagauay. She could kill anyone by simply raising her hand. However, if she wanted to heal those whom she had made ill by her charms, she could do so without any difficulty. It was also said of her that she could destroy a house by merely saying that she would do so.

By: Lahi.PH

The above is Jocano’s re-interpretation of classifications (the distinctions made among the priests of the devil) in Fray Juan de Plasencia’s document of 1589, Customs of the Tagalogs. Unfortunately, Jocano only notes the striking resemblance of the Biblical name Satan, ruler of the underworld, with Sitan of the ancient Tagalogs. This somewhat reinforces that Tagalog folk-Catholicism used the concept of Satan to create their own deity of the underworld.

Plasencia’s document contains a section titled “Relation of the Worship of the Tagalogs, Their Gods, and Their Burials and Superstitions”. This is where we find the entry on Sitan. It’s important to point out that Pasencia’s documentation notes sitan as a class of demons, not a deity.

“These infidels said that they knew that there was another life of rest which they called maca, just as if we should say “paradise,” or, in other words, “villageof rest.” They say that those who go to this place are the just, and the valiant, and those who lived without doing harm, or who possessed other moral virtues. They said also that in the other life and mortality, there was a place of punishment, grief, and affliction, called casanaan, which was “a place of anguish;” they also maintained that no one would go to heaven, where there dwelt only Bathala, “the maker of all things,” who governed from above. There were also other pagans who confessed more clearly to a hell, which they called, as I have said, casanaan; they said that all the wicked went to that place, and there dwelt the demons, whom they called sitan.”

“All the various kinds of infernal ministers were, therefore, as has been stated: catolonan; sonat (who was a sort of bishop who ordained priestesses and received their reverence, for they knelt before him as before one who could pardon sins, and expected salvation through him); mangagauay, manyisalat, mancocolam, hocloban, silagan, magtatangal, osuan, mangagayoma, pangatahoan.”

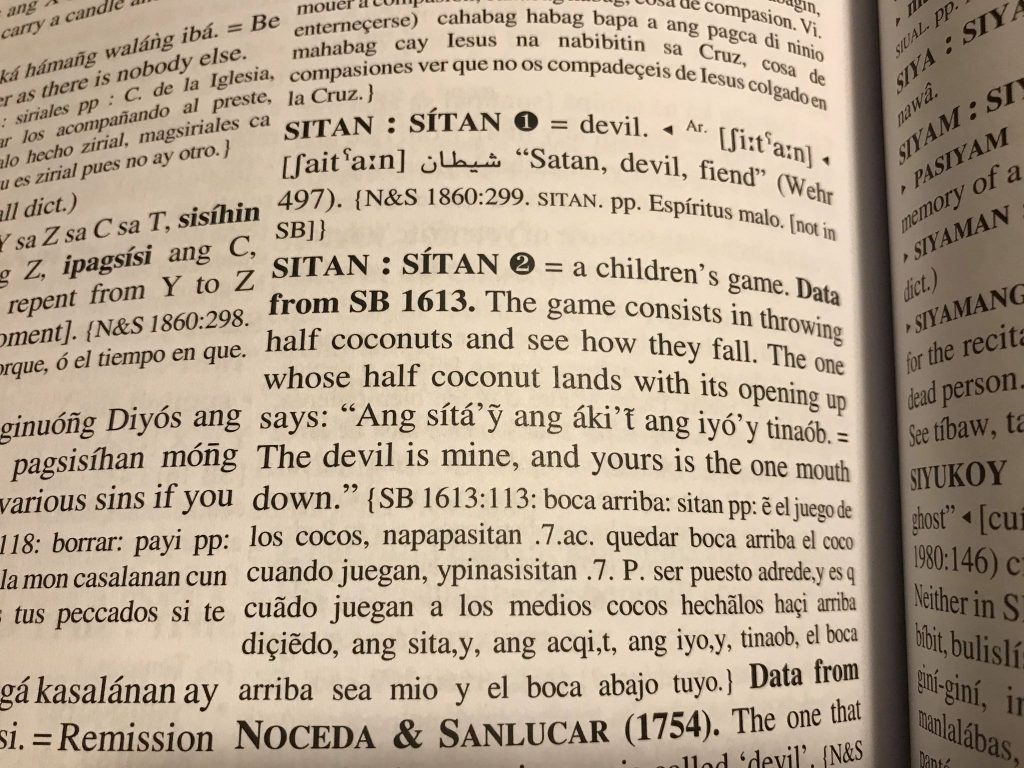

In Fray San Buenaventura’s 1613 Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala, Sitan is mentioned as a children’s game, yet still clearly associated to the ‘devil’.

By Jean-Paul G Potet

Etymology of Sitan

The original Hebrew term sâtan is a generic noun meaning “accuser” or “adversary”, which is used throughout the Hebrew Bible to refer to ordinary human adversaries, as well as a specific supernatural entity. The word is derived from a verb meaning primarily “to obstruct, oppose”. When it is used without the definite article (simply satan), the word can refer to any accuser, but when it is used with the definite article (ha-satan), it usually refers specifically to the heavenly accuser: the satan.

The word Šayṭān (Arabic: شَيْطَان) originates from the Hebrew (Śāṭān). However Arabic etymology relates the word to the root š-ṭ-n (“distant, astray”) taking a theological connotation designating a creature distant from divine mercy. In pre-Islamic Arabia this term was used to designate an evil spirit. With the emergence of Islam the meaning of shayatin moved closer to the Christian concept of devils. The term shayatin appears in a similar way in the Book of Enoch; denoting the hosts of the devil. Taken from Islamic sources, “shaitan” may either be translated as “demon” or as “devil”. Among Muslim authors, the term can also apply to evil supernatural entities in general as to evil jinn, fallen angels or Tawaghit. In a broader sense, the term is used to designate everything from an ontological perspective, that is a manifestation of evil.

The books Sahih al-Bukhari and Jami` at-Tirmidhi state that the shayatin can not harm the believers during the month of Ramadan, since they are chained in Jahannam – an afterlife place of punishment for evildoers.

Route to the Philippines:

Islam in Malaysia was introduced by traders arriving from Arabia, China and the Indian subcontinent. Islam introduced djinn & shaytan (jin & syaitan in Malay, meaning genies and demons) from Arabian legend into Malay folklore and folk beliefs. In many Malay belief structures, setan/sitan are used for incantations and are among the most feared spirits. I must admit that I was very struck by the similarity of human agents being used to induce maladies on behalf of Sitan in pre-Christian Tagalog beliefs. It also can’t be ignored how similar beliefs and superstitions are in Malaysia. Many areas shared an animist/ Austronesian base and were influenced by Hinduism and Islam. Hikayat Abdullah was a major literary work by Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, a Malacca-born Munshi of Singapore. It was completed in 1845 and first published in 1849, making it one of the first Malay literary texts to be published commercially. In it, Abdullah notes:

Their number I am unable to say. Their full nature I cannot explain. But I will mention them briefly: devils (hantu shaitan), familiar spirits (penanggalan), vampires, birthspirits (pelesit), jinns, ghost-crickets, were-tigers, mummies (hantu bungkus), spirit birds, ogres and giants, the rice planting old lady (nenek kebayan), apparitions, jumping fiends, ghosts of the murdered, birds of ill omen, elementals, disease bringing ghosts, scavenging ghosts, afrit, imps…There are so many occult arts the details of which I cannot remember, such as magic formulae to bring courage and subdue enemies, love philters, invulnerability, divination, sorcery, rendering a person invisible, for blunting the weapons of one’s enemy, or for casting spells upon them…Then I drew a picture of a woman, only her head and entrails trailing behind…I said, “Sir, listen to the story of the birth spirit.”

In the modern Malay Syaitan translates to “devil” or the concept of Satan (embodiment of evil).

Islam arrived in the southern islands of the Philippines, from the historic interaction of Mindanao and Sulu regions with other Indonesian islands, Malay islands and Borneo. The first Muslims to arrive were traders followed by missionaries in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. They facilitated the formation of Sultanates and conquests in Mindanao and Sulu. The Muslim conquest reached as far as the Kingdom of Tondo which was supplanted by Brunei’s vassal-state the Kingdom of Maynila. Muslim Sultanates had begun expanding in central Philippines in the 16th century, when the Spanish fleet led by Ferdinand Magellan arrived of Philippines. The Spanish conquest during the 16th century led to Catholic Christianity becoming the dominant religion in most of Philippines, and Islam a minority religion.

Conclusion

In my opinion, the concept of the devil and demons in Tagalog Mythology shares more in common with the syncretized Hindu and Islamic beliefs in Malaysia than it does with Christianity brought by the Spanish. The documentation by Plasencia and his Catholic mindset may have led the concepts down a path of Eurocentricity, but if you open yourself to comparative studies with surrounding countries, it paints a different picture. The Spanish certainly left their mark on religion throughout the Philippines, but there are also so many remnants of older beliefs in which they were absolutely powerless to dispel. The concepts of demons, the devil, and the ‘underworld’ existed before the Spanish arrived. This understanding goes a long way in grasping how a ‘new’ religion was able to supplant itself so quickly in the Tagalog regions. In the case of Sitan, I believe the notion was firmly in place at the time of Spanish arrival, so replacing the idea with Satan (a concept with a shared etymological origin) was likely quick work. I think it is also important to say that there may not have ever been a Tagalog deity named Sitan, but instead a class of demons that embodied evil and punishment, called sitan. With such a strong Islamic influence in the Tagalog region, the sitan may have been more like the Arabic zabaniyah – the forces of hell, who torment the sinners, also called the Angels of punishment or Guardians of Hell.

While the above is only a presented idea, I feel comfortable moving it into a likely theory after reading Ferdinand Blumentritt’s similar conclusion in the 1895 Diccionario Mitológico de Filipinas:

Saitan. The Tiruray people in the island of Mindanao used this to refer to a kind of malevolent spirit that inflicted illnesses upon people. It is highly likely that the term has Muslim origins. (compare: Sitan.)

Sitan. The designation used by the ancient Tagalog people to refer to a class of malevolent spirits. As the name would imply, these malevolent spirits are the demons of the Muslim religion.

SOURCES:

Blair & Robertson, op. cit., Vol. VII, pp. 185-196.

F. Landa Jocano (1969) OUTLINE OF PHILIPPINE MYTHOLOGY, Centro Escolar University

R Michael Feener; Terenjit Sevea (2009). Islamic Connections: Muslim Societies in South and Southeast Asia

Linda A. Newson (2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press

Nicholas Tarling (1998). Nations and States in Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press

Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press

Kirk Endicott (2015), MALAYSIA’S ORIGINAL PEOPLE: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF THE ORANG ASLI, NUS Press Pte Ltd

Tobias Nünlist (2015). Dämonenglaube im Islam. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG

Ferdinand Blumentritt (1895), Diccionario Mitológico de Filipinas

Abdullah (Munshi) (1849), Hikayat Abdullah

Jean-Paul G Potet (2017), Ancient Beliefs & Customs of the Tagalogs, Lulu

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.