In addition to folk stories of mythological creatures, enchanted objects, and natural deities, the Philippines is also home to various traditions of epic poetry. Similar to other epics from around the world, like the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, Greek Iliad, and Sanskrit Mahabharata, the epic poems of the Philippines tell rich, multi-generational stories of man’s struggle against their supernatural and natural surroundings, often involving gods and monsters. Even more importantly than telling exciting tales of adventure and adversity, these stories give us a broader cultural understanding of the society from which these stories emerged, but also give insight into the contemporary world as well.

Among the epics documented in the Philippines are Biag ni Lam-ang (Iloko), Hudhud (Ifugao), Maharadia Lawana (Maranao), and the sugidanon (Panay Bukidnon). This last epic is the one I’d like to focus on in this article. First documented in the 1950s by anthropologist Felipe Landa Jocano, the sugidanon (from Kinaray-a sugid, to tell) tells a story in ten chapters of powerful noblemen, demi-goddesses, and mythical creatures. It is still recited and taught to this day, in chanting sessions that can last for hours at a time, but for those of us who can’t visit a chanter in Iloilo and Capiz Provinces, our only introduction (like mine) can come through printed versions of the epic.

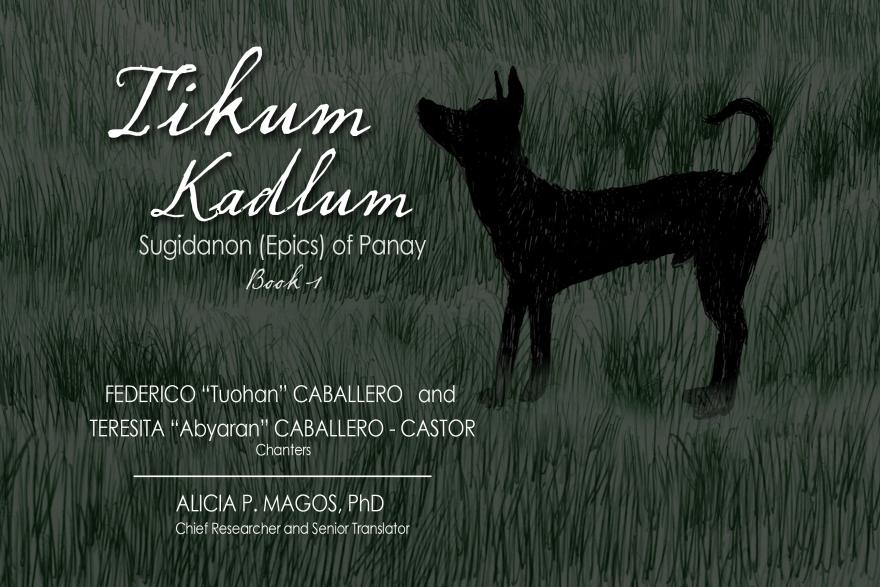

The first of these were Jocano’s Epic of Labaw Donggon and later Hinilawod: Adventures of Humadapnon, transcribed and analyzed from field recordings conducted while he was a student at Central Philippine University. While he never saw the publication of the complete epic, he laid the groundwork for future researchers to follow his work and discover more of the story. One of those is Dr. Alicia P. Magos, whose further research proved the existence of ten distinct parts of the sugidanon epic, which have since been recorded, transcribed and are currently in publication with the University of the Philippines Press in quadrilingual editions (Binukidnon, Kinaray-a, Tagalog, and English).

As with other epic poems, researchers have much to learn about both the past and the present from a careful study of the stories and the particular cultural emphasis (aspects of culture and behavior a story focuses on) they contain. In the case of the sugidanon, Dr. Magos and others were puzzled by the fact that the Panay Bukidnon tribe lives in the central mountains of Panay, while their epic tells of sailors, sirens, river mouths, and enchanted boats. From this, they were able to determine that the tribe had moved inland sometime in the past but still retained knowledge of their maritime history.

One startling feature of the sugidanon is that it was primarily chanted by women known as binukot, who were beautiful women usually from high-status families, secluded from childhood and trained in domestic arts like panubuk [embroidery] and memorization of the epic. This was done for a number of reasons: young girls would not be expected to work outside the home; wealthy families could afford to sacrifice their daughter’s labor; and her status as a chanter would mean she would merit a higher bride-price [bugay] when married to a man of similarly high status. The binukot was a highly regarded figure in her community, but socio-economic circumstances have changed significantly since the time of the epic’s composition, such that the only remaining binukot are now elderly. Current Panay Bukidnon tribal members learn the sugidanon in the classroom at one of various indigenous schools called Balay Turun-an [house of learning] and through hearing the epic recited during weddings or simply as a bedtime story.

The Magos-transcribed sugidanon as chanted by members of the Caballero family has become the new standard narrative for the epic for a few reasons. First, it is the only known complete recording of the entire epic instead of only the two episodes recorded by Jocano. Second, the participation of the Caballero family and their descendants in the continuing analysis and publication process gives this version greater credibility going forward. For these reasons, the following overview of the epic will center on the Magos transcription.

Of the ten volumes, most center on the characters Labaw Donggon, Humadapnon, and Dumalapdap, whose families intersect and intermarry as the tale progresses. Full descriptions of the chapters can be found here, or you can simply purchase them yourself and follow the story that way.

- Tikum Kadlum

- Amburukay

- Derikaryong Pada

- Balanakon

- Kalampay

- Pahagunong

- Sinagnayan

- Humadapnon

- Nagbuhis

- Alayaw

As the publication of the epic continues, the same questions that face Philippine folklore and mythology in general need to be answered in relation to the sugidanon. What can we learn about present populations from epics like this one, even though they’re separated from these traditions by several centuries and three colonial occupations? How can indigenous myth survive in competition with Western cultural exports? Is it enough to simply preserve the stories when the people who created them are currently in danger of forced migration and starvation?

These concerns and more are what drive anthropologists like myself and other interested parties to not only study these epics, but also increase awareness of them to the general public. By joining this with collaboration from the descendant communities of those who composed the stories, we can move towards a future that gives indigenous epics like the sugidanon the prominence they deserve in contemporary Filipino society but also in world literature as a whole.

Tikum Kadlum: Sugidanon (Epics) of Panay (Book 1)

David Gowey has a BA in Anthropology from Northern Arizona University and has been researching the Panay Bukidnon sugidanon since 2010. He speaks Tagalog, Hiligaynon, and Kinaray-a, and figures that as long as he keeps studying the Visayas, he should probably also learn Cebuano and Waray while he’s at it.