You’ve heard the stories of how the CIA used the aswang lore as part of their psywar operations against the Hukbalahap Rebellion in the Philippines. Well, it has been suggested that this wasn’t the first time such a strategy had been implemented – not by the Americans, but by Filipino strategists. The tale that keeps appearing in relation to these stories is that of Teniente Gimo from Dueñas, Iloilo and his attached aswang urban legend. Several times on The Aswang Project facebook page, people have mentioned that Gimo used the aswang stigma to frighten either Americans or the Japanese from entering Dueñas. In this article I will attempt to decipher the fiction from the fact.

Teniente Gimo: The Urban Legend

Stories regarding Teniente Gimo were not popularized until the 1960’s. One such story was famously documented by Dr. Maximo D. Ramos in his 1971 study, The Aswang Complex in Philippine Folklore.

AN ASWANG PARTY: This story was related to me by my mother. It is said that in the town of Dueñas, Iloilo, there was a barrio lieutenant by the name of Gimo. Tenyente Gimo had a daughter who was a teacher. This tenyente was known in the town as an aswang but the people didn’t have any evidence to prove it. One day his daughter arrived and she had with her a friend who was also a teacher. When evening came, the guest teacher was not allowed to go home to her own town. She was told to sleep in the house of Tenyente Gimo beside his daughter. When midnight came, the lady friend of the tenyente’s daughter woke up because of a noise downstairs. She went down slowly and she saw a very big kettle with boiling water, and there were the relatives, perhaps, of Tenyente Gimo. She heard that she would be killed that night. It was told where she slept, what clothes she had on, and the jewellery she wore. What the lady immediately did was to go upstairs and change everything she wore with those of the daughter of Tenyente Gimo and then ran away. What the tenyente had slain he recognized as his daughter. The young lady who ran away went to the police and reported what happened. They arrested the tenyente when they found that what the lady teacher reported was true. Next morning the tenyente was paraded through the whole town and they announced to the people that he was an aswang.

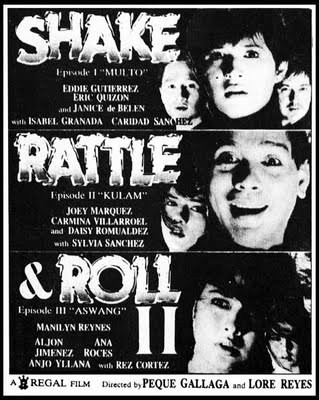

The Dueñas/ aswang premise was mainstreamed in the “Aswang” segment of Shake Rattle & Roll II (1990) – A barkada spend an outing in an eerily quiet town (Dueñas) of a faraway province (Iloilo) whose inhabitants are all vampire. Ana Roces plays the host as she tricks her best friend Portia (Manilyn Reynes) because on their fiesta, townfolks must eat a virgin for their celebration to be completed. Will Portia escape before she gets consumed by the townfolk? This was inspired by the urban legend of Tiniente Gimo in Dueñas, Iloilo.

Was Teniente Gimo a real person?

Various sources have suggested two names as being the ‘real’ Teniente Gimo. The first is Guillermo Guillerán Gavira, who is believed to have lived in the region during the turn of the 20th century and subsequent transition from Spanish to American control. The second is land owner Guillermo Labang, who lived in the region during the Commonwealth era of the Philippines (1935 to 1946).

Guillermo Guillerán Gavira: It has been said that Gavira was a voluntario during the Spanish regime and later a soldier with the forces who resisted the American occupation. It is believed that he opposed the teaching of English and would use his daughter to lure American teachers, who would then be murdered and eaten.

Historical Evidence: What I find particularly curious about this story is that, like the tale documented by Maximo Ramos, teachers are the victim. What’s more, Dr. Ramos states that the story was collected in Turburan, Cebu. On April 27th, 1905 a story was reported in several US publications where four American school teachers were murdered just north of Cebu. I can’t help but wonder if this story was changed to include supernatural elements to explain the human brutality and the locale changed to deflect blame. The majority of Maximo Ramos’ stories were collected during the 1950’s while he completed his dissertation paper, The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology. I would be curious to see if anyone knows of an earlier documentation.

There is no doubt that superstition and stories of the aswang were plentiful on Panay Island at this time. The tale of Senorita Concilacion de Ruiz of Dumangas was famously spread in an 1899 US publications under the title “Witch Women of the Philippines”. As explained to me by Peque Gallaga (while comparing the aswang stigmas in Dueñas and Dumangas), “If one is New York, the other is Chicago.” I point this out because it is important to remember that, while the aswang superstitions were widely spread on Panay Island, it was something that was relatively foreign and misunderstood by the Americans (more on this later).

Guillermo Labang: Labang was a wealthy land owner in Dueñas and eventually became the victim of growing jealousy among the poverty stricken townsfolk. They apparently spread rumors that a child was found dead on his land, innards strewn across the fields, and that it was Gavira himself – in aswang form – who had done the killing. According to rumor, these accusations did enough damage to Labang’s reputation that he had no choice but to share portions of his crops to dispel the stories and restore his reputation.

Historical Evidence: The only real evidence regarding this theory is that Guillermo Labang was really a land owner in Dueñas. Further, at the time, tenant farmers held grievances often rooted to debt caused by the sharecropping system, as well as by the dramatic increase in population, which added economic pressure to the tenant farmers’ families. As a result, an agrarian reform program was initiated by the Commonwealth. However, success of the program was hampered by ongoing clashes between tenants and landowners.

An example of these clashes includes one initiated by Benigno Ramos through his Sakdalista movement, which advocated tax reductions, land reforms, the breakup of the large estates or haciendas, and the severing of American ties. The uprising, which occurred in Central Luzon in May, 1935, claimed about a hundred lives. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that Labang took steps to decrease the economic pressure on tenants to avoid a similar clash. As to the aswang rumor, who knows?

Aswang: Crippling Superstition, or Brilliant Tactic?

As I mentioned above, the aswang folklore most certainly had a grip on the island of Panay and other parts of the Philippines long before the Spanish-American War and subsequent Philippine-American War. In fact, the aswang superstition has been documented as far back as 1589 where it appeared in Juan De Plasencia’s “Classification of Witches“. When the Americans arrived, there was a fascination with these superstitions that not only fascinated the soldiers, but also the general public back in the United States. So much was this fascination that a story recounted by a returning soldier was picked up at the national level. In it he recounts:

“When the American troops were making an advance one dark night on the town of Santa Barbara, in the island of Panay, a mob of half wild women and children broke into their lines all crying at the top of their voices, “Aswang! Aswang!” It seems that a large bat had made its appearance in their hiding place and so terrified them that they preferred to throw themselves on the mercy of their enemies than remain longer in its proximity.” ~PHILIPPINE SUPERSTITIONS as told by Charles Henry Wissner, a Returned Soldier, May 18, 1904

I can only speculate theories when I examine the above statement, but a few things are worth pointing out. In order to take the account at face value, we would need to believe that Filipinos scatter in terror at the mere sight of a bat – which they most certainly saw frequently. The story mentions women and children – which leads to a fairly legitimate assumption that the men were off fighting, or remaining hidden – possibly confirmed by the American referring to himself as the “enemy”. What seems a more obvious scenario to me is that the villagers were creating a distraction while the fighting men escaped. This tactic would play on the American’s lack of local knowledge regarding superstitions and their messiah complex of rescuing the woman and children, and Filipinos in general, from their own ignorance.

In Conclusion:

In my humble opinion, I believe the stories of Teniente Gimo are not tied to a particular person, but instead to the actual murders of American teachers in Cebu during 1905. Oral folk stories are adaptive by nature, and I think that similar tales exist regarding these heinous murders, but it was that of Teniente Gimo which became immortalized by Dr. Maximo Ramos and popularized by the Shake, Rattle & Roll series. The aswang superstition existed on Panay long before the Americans arrived, but evidence suggests it is possible that the documented cries of “Aswang! Aswang!” were a warning system and distraction implemented by the brave villagers resisting American rule. I think it is also possible that, in the travels of this story, it became confused with that of the American CIA psyops, and falsely attributed to Teniente Gimo in an attempt to dispel the negative stigma and create a hero. Filipinos love local heroes, but often forget that their country’s successes are built on the backs of the collective. Collectives like the brave women and children who potentially ran into the arms of the enemy so their menfolk could escape.

ALSO READ: The truth about the ASWANG in Capiz

PSYWAR in the Philippines | ASWANG of the CIA

Additional Sources:

Guillermo Guillerán Gavira research conducted by Guillermo Gómez Rivera

Guillermo Labang research conducted by Nereo Cajilig Luján

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.