THE BOAT-COFFIN BURIAL COMPLEX IN THE PHILIPPINES AND ITS RELATION TO SIMILAR PRACTICES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

Author: Rosa C. P. Tenazas

Source: Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, Vol. 1, No. 1 (MARCH 1973), pp. 19-25 Published by: University of San Carlos Publications

A preliminary report on boat-coffin burial in the Philippines was read by the author in the divisional meeting on prehistory and archaeology of the 11th Pacific Science Congress held in Tokyo in 1966. Since then more data have been collected . The present paper is not intended to be comprehensive. However, a detailed report will be presented aft er a full analysis of associated skeletal material which exhibit artificial cranial deformation has been made.

The phenomenon known as “boat-coffin burial” is a mode of disposal of the dead in hollowed-out pieces of logs generally in the shape of a boat. This was a widespread practice throughout Southeast Asia from prehistoric times and, in the Philippines at least, is known to exist in certain areas to the present. The practice of boat-coffin burial in the Philippines was briefly noted in earlier explorations by foreign scholars. However, the first mention of boat-coffin burial as such appears in Robert B. Fox’s (1963) preliminary report of excavations in western Palawan. The earliest known archaeological explorations were conducted by Feodor Jagor and Alfred Marche in the late 19th century. Subsequent discoveries were made in the 1920’s by American colonial officials followed by more systematic surveys such as the University of Michigan expedition headed by Carl Guthe and the explorations of H. Otley Beyer, the pioneer anthropologist/ archaeologist of the Philippines (see Marche 1970; Guthe 1929 and Beyer 1947).

Previous to the present study the distribution of boat-coffin burial in the Philippines had not been seriously considered. Neither has interest been sufficient enough to relate it to similar practices already reported elsewhere in Southeast Asia and Oceania (Doerr 1935; Vroklage 1936). In the mid 60’s, simultaneous researches were carried out by the National Museum and the University of San Carlos in Cebu City on boat-coffin burial per se. The National Museum team explored the island group of Romblon province while the University of San Carlos team concentrated its researches on the islands of Cebu, Bohol, and neighboring islets. The researches themselves were a follow-up of surveys already reported by Beyer (1947). Primarily on the basis of these researches and the summarized report by Beyer of earlier surveys (1947), at least fifty sites have been located. Forty of these are concentrated in central Philippines with the island of Bohol, so far, yielding the highest number of sites. The other islands in which boat-coffin burial is, at present, known to the author are: Mindanao, Luzon, Palawan, Negros, Panay, Marinduque, and Masbate. Type sites are caves and rock shelters, generally accessible from the sea. Although early Spanish ethnography reports on large boats involving multiple burial, this type of burial has yet to be discovered. For instance, on burial customs among the Bisayans in central Philippines, a late 16th century account states:

“In some places they kill slaves and bury them with their masters in order to serve them in the after life; this practice is carried out to the extent that many load a ship with more than sixty slaves, fill it up with food and drink, place the dead on board , and the entire vessel including the live slaves are buried in the earth(Quirino and Garcia 1958: 415-516).”

Again, in the island of Bohol, it is said of a chief that he “had him self buried in a kind of boat, which the natives call barangay, surrounded by seventy slaves with arms, ammunition, and food – just as he was wont to go out upon his raids and robberies when in life (Blair and Robertson 40: 80-81).” In the Rejang River area of Sarawak, Borneo, where the idea of a soul boat exists, certain structures for the repository of the dead are built. One type consists of a pillar or pillars into which niches are carved for the bodies of slaves and followers. In a hollow at the top is the jar which contains the bones of the chief (Roth 1968: 146- 15O).

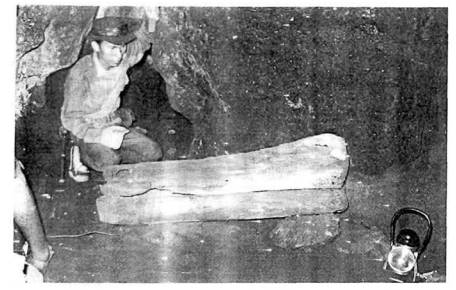

Typologically, there are two kinds of burials: primary and secondary burial. In the first type the burial was made in wooden boat-coffin, if not an actual boat, and laid in a cave or rock shelter. Early ethnographic reports are not confined to descriptions of multiple burial. Instances of individual burials in boat-coffin are also mentioned. One account states that when a chief died among the Tagalog “he was placed beneath a little house or porch … and afterward laid on a boat which served as coffin or bier (Blair and Robertson 7: 194)” A more graphic description from Cagayan, northern Luzon, is given by Quirino and Garcia (1958: 396):

“They bury them in a hole two fathoms deep, four fathoms long, and a fathom and a half wide, where a baroto (boat) sawn in half (is buried): the lower half, whole, and the upper (cut) in two pieces like doors; and a wooden piece through the same opening, two mats are placed on top and there they put small bits of areca nut, lime, betel nut. They put two small blankets on each side of the deceased. Two tiny plates on each side. Small jars of oil and other fragrant oils. Two trays, one at the head and the other at the foot. Covering everything with earth, and later they build a shelter over the sepulcher.”

In secondary burial the skeletal remains, sometimes only the skull, were reburied either in miniature wooden boat-coffins or in jars. In one of the Batungan caves in Masbate, Warren Smith discovered along with a number of deformed skulls, a skull box carved with crocodile-head handles (Beyer 1947: 264-265). In 1881, Alfred Marche discovered an undisturbed secondary boat-coffin/jar burial cave site in Marinduque. Inside he found piles of miniature wooden boat-coffins, averaging 90 cm in length and, behind these, stoneware jars of probable 12th – 13th century Chinese export types also containing burials. His discoveries extended to the fact that multiple secondary burial as well as skull deformation was practiced (Marche 1970: 178-181). In the practice of secondary burial in boat-coffins we see an overlapping of the widespread belief that the final journey of the soul cannot be effected until all the flesh has been removed from the bones.

The traditional boat-coffin later came to be replaced by a simple wooden coffin, cist grave, or jar. In Celebes, for instance, stone cist-graves are known as kalamba, meaning boat, while ordinary coffins carry the name bangka, another term they use for boat. In central Nias and in Sumba, boat terms for wooden coffins and stone urns are owo and kabang, respectively, which terms also apply to wooden coffins in Kamera, stone urns in Lamboja and cist graves in Wajewa in the Lesser Sundas (cf. Vroklage 1936: 727 ff.). In the north, in one of the islands of the Ryükyüs, people have their coffins made in advance which they refer to as their boats (Kokubu and Kaneko 1962:92).

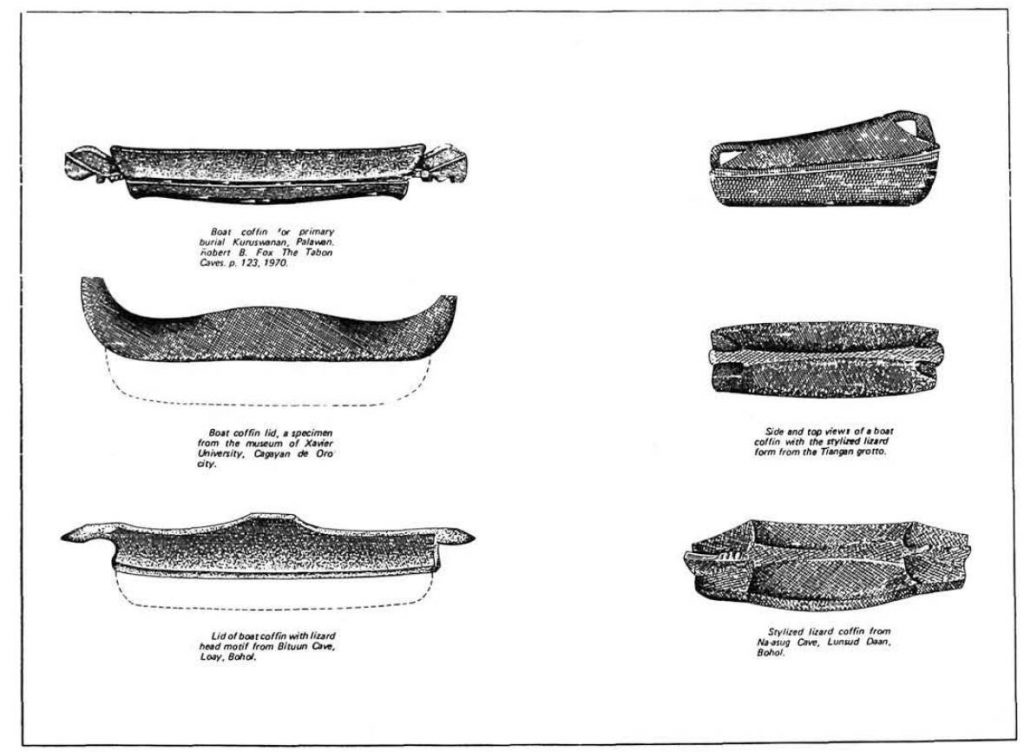

Generally, the boat-coffin in the Philippines is made of two parts (split-log fashion) carved out of certain species of hard wood. The lower portion is semi-circular in cross-section, sometimes provided with perforated side projections for lashing the parts together. The lids or covers are carved like a saddle roof with ends curving upwards. Lizard heads decorate the projecting ends of lids seen in several Bohol and Cebu sites while the crocodile motif is favored in the Romblon sites. From two separate sites in Bantayan Island off northern Cebu and in a cave in Lamanok Point in Anda, Bohol, were collected small boat-coffins which are almost identical in the carving of their entire covers into stylized representations of a lizard. The average length of boat-coffins for primary burial is two and a quarter meters while boat-coffins for secondary burial measure only about ninety centimeters.

Photo by : Jordan Clark

In Niah Cave in Sarawak, Borneo, a “ships of-the-dead” chamber was discovered by the Harrissons (1958: 586 ff.). Scattered on the floor were what, at first, were mistaken for ordinary Dayak perahus or river boats. The carving on each was a “sabre-toothed dragon or tooth-bared crocodile.” Against the wall were paintings in red haematite of representations of boats. In a tiny coral islet off the above mentioned Lamanok Point site in Anda, Bohol, a rock shelter site was discovered by the author which yielded, perhaps, the first prehistoric rock painting in the Philippines. This is not to be compared to spectacular paintings which have been discovered in this part of the world. The paintings discovered in Bohol consisted of simple impressions of hands dipped in a mixture of red haematite. Natural concavities on the exposed limestone floor still bear encrustations of the red mixtures.

Up to the turn of the present century boat coffin burial was known to be in practice among the Bagobo of Mindanao. Benedict (1916: 186-187) reports that

It was formerly the custom when the datu died to carve the head and lid of his coffin into the shape of a crocodile’s head … In ordinary burials, a conventional pattern of lozenges and zigzags made from strips of red or white cotton cloth is tacked on the black cloth that covers the sides and lid of the box, thus producing a highly schematic representation that is called buaya, or crocodile.

It should be mentioned that the crocodile motif was also used among the Bagobo to ward off evil spirits. In the Kinabatangan River area, North Borneo, boat-coffins with buffalo and lizard or crocodile designs were discovered by C. V. Creagh (Roth 1968: ccxi) who gave the following explanation:

Coffins ornamented with protruding heads of buffaloes or cows contained male skeletons, while figures of snakes, lizards, and crocodiles appeared to be used for the decoration of those of the women and children.

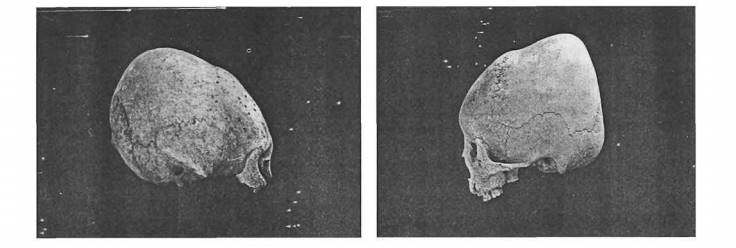

Due to the extremely disturbed condition of the sites investigated by this author, it has not been possible to make analysis along the same lines. Of the known boat-coffin sites, at least seventeen have established association of artificial cranial deformation. Skull deformation, however, does not appear to belong exclusively to groups which practiced boat burial. From a privately dug 13th-14th century site in Liloan, Cebu, the author in company with Leonisa L. Ramas and Margaret Sullivan, was able to collect five deformed skulls. Apparently the practice was also widespread among groups which practiced simple inhumation burial; two deformed skulls were previously collected by Ramas from a similar site in the island of Mactan off Cebu City. All the deformed skulls hitherto collected by this author were from definite boat-coffin burial sites in Cebu and Bohol. Additional information on site locations of artificial skull deformation can be obtained from Scott (1968:36). lt should be pointed out that the nature of the geography of the Philippines has not been favorable to cultural uniformity either in prehistoric times or the present (indeed this is also true of lndonesia and mainland Southeast Asia). Regional isolation resulted in a mosaic of sub cultures each developing distinctively with occasional overlapping of one or the other associated trait so that in a given cultural phase, say, the late lron Age, contemporaneous groups with different burial traditions (e.g. jar burial, boat burial, simple inhumation burial and, perhaps, even cremation burial) practiced cranial deformation as well.

In the Philippine type of deformation the anomaly is invariably situated in the frontal bone. It is fortunate that we are provided a partial explanation of the practice through analogy. The Melanaus of Sarawak, Borneo, have kept the traditional concept of a soul boat in connection with burial and, in addition, are also known to practice cranial deformation. The following is a graphic description by Aikman (Harrisson 1959: 85-86):

Among the female Melanaus a concave forehead was considered a sign of beauty and steps were taken to insure that the girls should conform to this ideal of Melanau beauty. While still in infancy the bones of the skull are subjected to pressure by means of an ingenious instrument known as jah or api. This instrument consists of a piece of hardwood about 2 ft long having holes bored through each end. First a cloth covered weight is placed on the baby’s forehead and on top of this weight is the hardwood jah. This is fixed to the infant’s head by a cord extending through the holes at each end of the piece of wood and passing behind the head. The cords … are tightened by means of screws.

Quoting from reports Roth (1968: 79-80) gives similar descriptions of the practice among the Melanaus:

It is considered a sign of beauty to have a flat forehead, and although chiefly practiced on female children, boys are occasionally treated in the same manner..

.. I have often watched the tender solicitude of the mother who has eased and tightened the instrument twenty times in an hour, as the child showed signs of suffering … Before the child is twelve months old the desired effect is generally produced, and is not altogether displeasing.

In another report it is said that

the tadal (same as the jah) … is only placed on the child ‘s head during the time that it is asleep … Its use is first commenced when the infant is fifteen days old, and is continued until the third or fourth month. In the early stages only very slight pressure is applied, but gradually it becomes more and more severe. Only female children have heads flattened in this way.

In archaeological context the only parallel of skull deformation known to this author is a single specimen from an urn burial in Anjar, west Java (Heekeren 1956: 200). Preliminary analysis of the deformed skulls collected by this author shows these to be of the female sex. The conclusion was based upon morphological observations following some of the criteria for distinguishing sex in skeletal material. Specialists are in agreement that of all the parts of the skeleton the pelvic bone yields the most reliable sexing information. When this is absent a degree of reliability can be obtained from skulls by noting certain features such as: the round and sharply defined margins of female orbits as compared to the relatively low and indistinct borders of these in the male; comparative thickness of the male vault; pronounced supra orbital torus of male skulls as compared to moderate traces of these in the female; relatively slender and gracile zygomatic arches in female skulls; more developed mastoid processes in the male and, finally, the general refinement of the female skull as compared to the male in terms of muscle attachments. Deformation unfortunately restricts the number of useful metrical recordings that can be obtained from the skull, cranial indices being of least value. Brothwell (1965) may be referred to for more information.

Photo by: Jordan Clark

There are at least three interpretations for the ritual use of the boat in Southeast Asia: as a means by which spirits of diseases are exorcised; as the shaman’s vehicle in his search for the patient’s soul; and its use in connection with the death ritual (Eliade 1964: 356 ff.). Since we are more concerned with the uses of the boat in connection with shamanism and the death ritual, we shall dispense with its use in the first category. Among contemporary marginal cultures in central and Southeast Asia which practice shamanism with strong cosmic orientation, the boat has become either a symbol for the cosmic axis or a substitute for the shamanic vehicle or the psychopomp. According to Eliade (1964:357) the idea of the use of the boat as a shamanic vehicle was an Indonesian innovation of the shamanic technique of celestial ascent. Thus among the Sea Dayak when the shaman treats a sick person, it is believed that her soul goes up to the roof of the house and calls for her boat which is the rainbow (Wales 1957: 90-91). The Ngadju Dayak have a map of the afterworld which shows a soul boat traversing the sky by way of the rainbow while among the East Torajas the boat itself is interchangeable with the rainbow (Wales 1957: 98). The rainbow-bridge myth is familiar in early Philippine ethnography. In his Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas written in 1582, Loarca (Blair and Robertson 5: 129 ff.) writes on the death practices of the Bisayans: “The souls of those who are stabbed to death, eaten by crocodiles, or killed by arrows (honorable deaths) go to heaven by way of the arch which is formed when it rains, and become gods … ” Further, it is said that “when the Yligueynes (inhabitants of Cebu and Bohol) die, the god Maguayen carries them to Inferno . . . in his barangay (boat).” The Tagbanua of Palawan also believe in a soul boat. According to them those who die in an epidemic are carried to the sky in ships-of-the-dead (Fox 1970: 114). Likewise, it is widely believed among the Bilaan of Davao in Mindanao that when the body starts to decay it is time for the soul to sail away in a boat (Cole 1913 :144).

It was previously mentioned that the motifs most frequently encountered in boat-coffins in the Philippines are the lizard and crocodile. An interesting interpretation of the beast bird and fish symbolism in Southeast Asia is given by L. G. Loeffler (1966) . He states that in the tripartite view of the universe the underworld is represented by the fish (alternately, lizard, snake, or crocodile), the present world by the beast of sacrifice (buffalo, cow, pig, etc.), and the sky, by the bird. Alternately, the underworld as represented by the fish may also be conceived of as prenatal life while the bird symbol relates to the postmortal state . The underworld symbols and the cosmic axis representations constitute what Raats (1969: 59-64;87) calls the “horizon”, where earth and sky meet. The role of the boat symbol as an alternate to the rainbow is to connect the underworld with the skyworld. Since the bird represents the sky, the soul boats of the Ngadju Dayak are also shaped like hornbills (Loeffler 1966, after A. Steinmann: Das kultische Schiff in Indonesien 1941; see also Wales 1957: 90-91). Likewise, the Lhota and Konyak Naga bury their dead in hombill-decorated coffins which they call boats (Loeffler after J. P. Mills: The Lhota Nagas, 1922 and H. E. Kaufmann: Deutsche Naga Hills Expedition 1939). At this point we recall the famous Dongson drums in which representations of soul boats carry bird shaped men (Wales 1957: 58). Van Heekeren (1958) shows a drawing on a kettle drum recovered from Sumbawa of a soul boat filled with bird-shaped men. The bird, fish, and beast symbols are clearly represented here. As a final illustration of the original meaning of the ritual use of the boat in connection with death we have a Neolithic jar cover found in Tabon cave in western Palawan (Fox 1970). In it are two figures sitting in a boat, the one behind (the shaman? ) in the act of paddling the spirit of the deceased, represented by the figure in front with arms crossed over the breast, to the afterworld. This soul boat is presumed to originally have a mast (cosmic tree? ). According to Eliade (1964: 357-358) the role of the boat in the ecstatic journeys to the afterworld either to carry the dead or to search for the patient’s soul, is manifested by the presence of the cosmic tree in the shaman’s boat. An excellent illustration may be seen in Wales’ (1957:91) figures of Ngadju Dayak boats- of the-dead.

Photo by: Jordan Clark

It has been suggested that boat-coffin burial was a development by riverine and maritime peoples of Southeast Asia who thought of the boat alternately with the rainbow as carrying the souls of the dead to the afterworld (Wales 1957:98). As the idea diffused farther to Oceania it appears that a modification took place. Here the concept behind the canoe burial seems to be tied up with memories of distant migrations and of the subsequent return to the land of the ancestors. This idea is dramatically demonstrated in the orientation of the corpse when this was set out to sea in its canoe coffin: the feet point to the direction where the ancestors are believed to have come from (Doerr 1935: 746;Vroklage 1936: 755).

Boat-coffin burial in the Philippines is too complex to assign to it a single source of origin. The types encountered here are the result of the convergence of different traditions in the process of diffusion.

REFERENCES

Aikman, R. G.

1959 “The Melanaus.” In The Peoples of Sarawak, edited by Tom Harrisson. Sarawak: Sarawak Museum.

Benedict, Laura W.

1916 A Study of Bagobo Ceremonial, Magic and Myth. New York: New York Academy of Sciences.

Beyer, H. Otley.

1947 “Outline of Review of Philippine Archaeology by lslands and Pro vinces .” The Philippine Journal of Science 77:205-374.

Blair, E. H. and J. A. Robertson (eds.)

1903-1909 The Philippine Islands. 55 vols. Cleveland: A. H.Clark and Company.

Brothwell, Don R.

1965 Digging up Bones. London: Toe British Museum of Natural History.

Cole, Fay – Cooper.

1913 The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao. Field Museum of Natural History. pub. 170, Anthropological series 12: (2). Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Doerr, Erich.

1935 “Bestattungsformen in Ozeanien.” Anthropos 30:369-420; 727-765.

Eliade, Mircea.

1964 Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstacy. Translated from the French by Willard R. Trask. Bollingen Series LXXVI, Pantheon Books.

Fox, Robert B.

1963 Ancient Man in Palawan: a Progress Report on Excavations. Manila: National Museum.

1970 The Tabon Caves; Archaeological Explorations and Excavations on Palawan lsland, Philippines. Manila: National Museum.

Guthe,Carl E.

1929 “Distribution of Sites Visited by the University of Michigan Philippine Expedition 1922-25.” In Papers oJ the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts and Letters, edited by Eugene S. McCartney and Peter Okkelberg. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Harrisson, Tom.

1958 “The Caves of Niah: A History of Prehistory.” The Sarawak Museum ]ournal 8: 549-595.

Heekeren, H. R. van.

1956 “Note on the Proto-Historic Urn Burial Site at Anjar, Java.” Anthropos 51:194-200.

1958 The Bronze-Iron Age of Indonesia.

The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. Kokubu, Naoichi and Erika Kaneko.

1962 “Ryukyu Survey 1960.” Asian Perspectives 6: 77-138.

Loeffler, Lorenz G.

1966 Beast, Bird and Fish; an Essay in Southeast Asian Symbolism. Paper Read in the Symposium on Folk Religion and World View in the Southwestern Pacific,Eleventh Pacific Science Congress, Tokyo.

Loewenstein, Prince John.

1958 “Evil Spirit Boats of Malaysia.” Anthropos 53: 203-211.

Marche, Alfred.

1970 Luzon and-Palawan. The Filipiniana Book Guild, voL 17. Manila: The Filipiniana Book Guild.

Quirino, Carlos and Mauro Garcia (trans.)

1958 The Manners, Customs, and Beliefs of the Philippine Inhabitants of Long Ago: Being Chapters of “A Late 16th Century Manila Manuscript”, trans lated and annotated. The Philippine ]ournal af Science 87: 325-453.

Roth, Henry Ling.

1968 The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. 2 vols. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press.

Scott , William Henry.

1968 Prehispanic Source Materials far the Study of Philippine History. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Press.

Tenazas, Rosa C. P.

1966 Preliminary Re port on the Boat Coffin Burial Complex of the Philippines. Abstract of Paper. Proceedings of the Eleventh Pacific Science Congress, Tokyo.

Vroklage , B. A. G.

1936 “Das Schiff in den Megalithku lturen Südostasiens und der Südsee.” Anthro pos 31: 712-757.

Wales, H . G. Quaritch.

1957 Prehistory and Religion in South-East Asia. London: Bernard

ALSO READ: Psychopomps (Death Guides) of the Philippines

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.