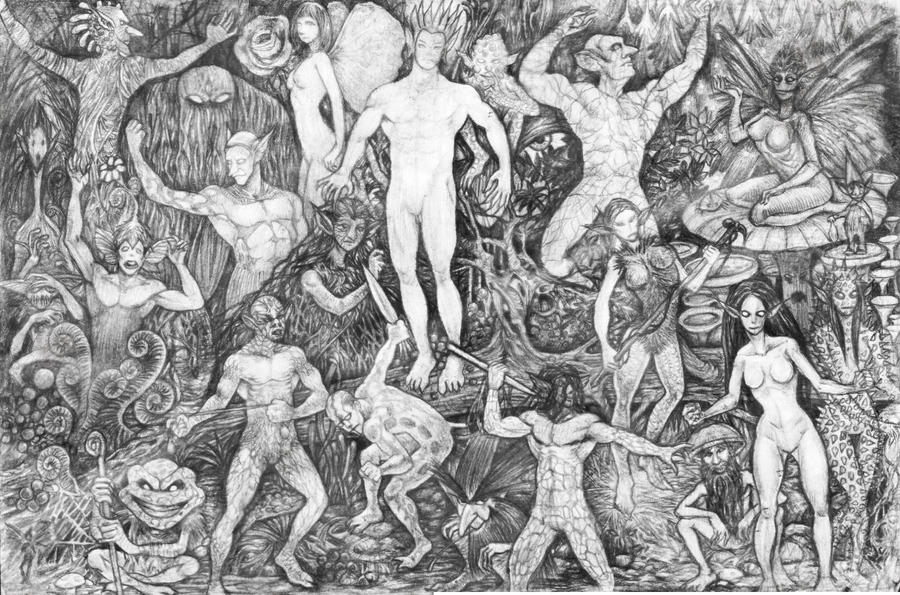

IN THE LANGUANGE of folklore, elves differ from fairies in that they are loners, while fairies have social organizations. Elves may have families but have none of the larger social groups that the European fairies have.

There are fairy courts, dances, and social ranks, but elves live as isolates or in groups no larger than nuclear families.

The fairies are forest dwellers like the elves, too, but they have kings, queens, princess and princesses, and nobles and their ladies and serving men and women. There are no such ranks and social organizations among elves.

In a country with some 187 native languages (according to ethnologue.com) — 80 by which no intercommunication is possible —the elves are known by a wide variety of names. These include:

aghoy — Waray

dalakitnon — Waray

dayamdam — Agusanon

engkantada, engkanto — Bikol, Sugbuhanon, and other Hispanized groups

kamanati-daplak — Zambali

kiba-an — Iloko

palasekan — Ilongot

ragit-ragit — Romblomanon

tamawo — Hiligaynon

tirtiris — Iloko

wenri-wenri — Romblomanon

Rural Filipinos seem oblivious of who own the fruit trees they raid by the wayside. They just pick the fruit of trees they pass by without asking permission from the owner. But they are most careful to beg the elves thought to reside in the trees to let them do so. Before he cuts down a tree, the Ilokano says:

Bari-bari;

Dikay agungunget, pari,

Ta adda papukan diay padi.

(Your excuse, please:

Be not angry, friends,

For the priest asked us to fell something.)

Villagers are careful not to throw things in their yards, particularly after sunset when elves are said to be there, without saying:

Kayo-kayo! (Away, away!)

Elves whose premises are trespassed are said to throw dust into the trespassers’ eyes and to give them skin rashes and permanently twisted lips. The folk healer cures these afflictions by casting rice on the premises violated and expressing regret for the trespass.

Some children are said to lose their hair to the foot- tall female kiba-an, which steals the hair to keep hers long enough to reach her feet that point in the wrong direction. Further theft of the hair is prevented by crushing flies on the bald scalp and rubbing them on.

The kiba-an is also blamed for coconuts having too little water and meat, and the creature can be driven off by smudging the trees with burning bovine hooves. It steals greens from gardens and, cornered, turns itself into a paling in the fence which screams in pain when the gardener sweeps the fence with a stick. The kiba-an are also kept away from fish traps in streams by displaying small bamboo crosses on the traps. No such crosses are needed for traps set in tidal waters since demonological beings, except the merfolk and dragons, are said to fear salt water.

The favorite domiciles of elves and their neighbors— namely the demons such as the kapre—are the kalumpang and the dalakit. These trees have thick leaves and their branches gracefully arch down and they often dominate the landscape. Termite mounds develop under them, and since these mounds are thought to be the gateway of dwarfs into their underground realm, the folk keep away from them.

Elves are said to climb into trees by way of the bagbagutot, a shrub with tiny edible black berries. It clambers up the trunks of trees in thickets.

A large kalumpang tree stands across the street from the Chemistry department of the University of the Philippines, in Diliman, and the stink from its fly- pollinated blooms compete with that from the nearby laboratories. An even larger such tree stands beside the Marikina Road across from St. Joseph’s Church in Quezon City. Another large such tree stood on top of the seventeenth-century wall of Intramuros, in Manila, right next to the Manila Bulletin building until it was felled by some brave souls recently.

The tree from which the dalakitnon (‘one who lives in the dalakit tree’) got its name is the dalakit. It starts as a seed dropped by a bird or bat in the crotch of a tree in the moist jungle, germinates there, and slowly sends roots around the trunk of its host and on down into the ground. As the seedling grows, its roots enlarge and tighten their hold around the host tree. They go on multiplying and enlarging till the trunk of the host withers and leaves a hollow where bats, owls, snakes, monitor lizards, and geckos den. The tree sends down adventitious roots from its low-hanging branches as well. The tree and the sounds made by the creatures denning in it inspire awe and fear in the beholder.

Gilda Cordero-Fernando, fictionist and publisher of coffee-table books, has a large dalakit growing in her front yard in Quezon City. This impressive-looking tree is a centerpiece in the yards of same large residential homes in Manila’s suburbs.

Elves and the Philippine version of the Arabian genie, locally known as the kapre, are said to live in various large trees but especially prefer the Sterculia foetida, known to Ilokanos as bangar, to Tagalogs as kalumpang, and to Visayans as bubog. It is a handsome tree, its palmate leaves thick and its branches arching down. It is not suitable as an ornamental tree, however, because it bears tiny inconspicuous blooms that smell like feces and are pollinated by flies and for this reason are called takang demonio (‘demon’s excrement’) by the Mt. Pinatubo Negritos in Zambales.

Some elves are just a few inches tall and others about a foot, but the rest are six-footers or taller. The tall elves include the dalakitnon of the legend about Gloria. They freely interact with humans, going to public dances, driving flashy new cars, and winning beauty contests. Some of them even go on fellowships in Europe and North America. But they all live in trees in the Philippines. People imagine that the dalakit and kalumpang are trees but these are elf mansions and some have heard the clink of elf plates in elf kitchens and dining tables in these trees.

A pretty college girl from the city once went with her classmate to the latter’s quiet frontier village to spend her summer vacation there. She met a tall, blond youth at a village dance given in her honor. They danced and danced and then she agreed to go with him and visit his folks that same night. In his gleaming sports car they drove to a wondrous city with bright lights, wide streets, and splendid homes. She was found weeping alone in the deep woods next day after a long and anxious search by the village folk.

The lack of social organizations among these early Philippine deities helps explain the Filipino’s inability to form and maintain his. Filipino clubs overseas quickly break up into warring splinter groups, usually along linguistic and regional lines, and this in spite of 500 years of Filipino apprenticeship in social living under the Spaniards and Americans.

The special attraction of the dalakitnon to Gloria was that he had the physical traits of the conquering Spanish and American Caucasoid—tall, light-complex- ioned, blond, his nose long and narrow, and his eyes blue rather than dark brown or black like a Filipino’s.

The elves in some Philippine legends also have no philtrum—the depression on the upper lip beneath the nose. The Visayan engkanto has such a transparent throat that water can be seen going down his pharynx when he drinks. The kiba-an have gold teeth and grin to light their path on dark nights.

Over the centuries Philippine girls have preferred whites to blacks or browns as dating partners and spouses. During the Spanish conquest the native males often complained that the girls were always leaving them to join white Spaniards. This writer was at the beach in Southern Zambales before daybreak on January 30, 1944, when an American invasion force landed to cut off the fierce Japanese defenders of Lingayen Beach up North. He then saw many Filipino girls running out to offer green coconuts to the white Americans, some even holding hands with them. But the same girls fled in panic when the black contingents, landing separately, came ashore.

Mangyans with Caucasoid features were reported in the 1960s to be living in an isolated community in Mindoro Island. They were said to be descendants of seventeenth-century Dutch sailors whose warship capsized off the coast of the island. This is possible because the Spaniards fought off several Dutch naval invasions near the mouth of Manila Bay in the seventeenth century.

The number of white men’s offspring around Philippine military bases occupied by Americans is far larger than the black men’s children though there have not been many more whites than blacks at these bases.

In 1974 this writer saw a barefoot road worker with a white man’s features on the construction site of the Pan-Philippine Highway in Samar during a trip through the area. He and the children of white American and brown Filipino liaisons of today and the recent past will be among the elves in tomorrow’s legends. Whites have also increased in numbers with the coming of multinationals in banana and pineapple plantations in Mindanao, and the presence of mining prospectors, crocodile and orchid hunters, scuba divers, and tourists and businessmen. In short, accounts like these were evidently invented by Filipinos eager to keep their dating partners and spouses.

A legend of the vanishing hitchhiker, common in the West, is told by a parish priest from Lobo, Batangas. He was driving his Volkswagen one night when he heard the door open and close with a bang. He switched on the light in the car and saw an attractive woman in a red dress in the back seat. He drove faster because of fear. Then he heard the door close with a bang and found her gone when he looked.

A similar legend is told by another Batangas priest.

He was on the last bus from Manila and a woman in red beside him asked for a cigarette. He gave it to her and she smoked it and then asked for another. He gave that to her, too. He then got off at a comer with some of his parishioners at 10:00 p.m. and asked them if they knew the woman. They replied that they never saw her.

In some legends, elves offer unpolished rice, called “engkanto rice” in Quezon Province, to their intended captives. It is said that if one eats the rice, it turns into worms in his mouth and he remains in the elves’ power. This belief helps explain why rural Filipinos refuse to eat unpolished rice no matter how often they are told that higly polished rice does not contain the anti-beriberi Vitamin B1 found on the seed coat of unpolished rice.

The Iloko word naugaw describes a person wasteful of rice. It is derived from ugaw, an elf. The folk level the rice in a bin and place an inverted coconut-shell bowl on it to keep elves away. A string of empty snails is also laced around the neck of a jar used as a rice bin to keep elves away by the tinkle of the shells when these creatures clamber up the sides of the bin.

It may be that because this writer (Maximo Ramos) often heard it as a youngster, his favorite folktale is one his mother often told at bedtime. She was a fine raconteur and a good reader but had not been taught how to write for fear that like Gloria in the legend, she might write letters to suitors not on the approved list. Her tale was about Juan and the bangar tree, and it went this way:

Juan’s widowed mother kept begging him to go to the forest and get some firewood because her woodbox was empty. He kept saying he would go but never did. But one morning when she began weeping, he put his axe on his shoulder, walked into the forest, stopped at the foot of a bangar tree, and playfully said:

“I will cut you down, bangar,/ To be my mother’s mortar.”

A kiba-an came down from the tree and said, “Spare this tree, Juan, for my wife has just given birth.” The kiba-an then produced a small clay pot and added, “For your kindness, I will give you this pot. You need only hold it up and say ‘Rice still hot/ And pork in my pot’ and it will give you all the food you can eat.”

Juan took the pot and left.

Night fell on his way home and he stopped in a hut by the road. He begged for shelter and the widow housekeeper let him in. He took out his magic pot, said Rice still hot/And pork in my pot,” and they feasted on steaming rice and sizzling pork.

The widow woke him up early at dawn, gave him a pot that looked just like Juan’s pot, and he left.

Juan’s mother was displeased to see that he had brought no firewood home. He said she had no need for firewood, took out the pot, and said, “Rice still hot/ And pork in my pot.”

Neither rice nor pork appeared in the pot and he smashed it, picked up his axe, soon stood at the foot of the bangar tree, and said, “I will cut you down, ban- gar,/To be my mother’s mortar.”

Down came the father kiba-an holding a small purse. He shook the purse and bright pieces of gold fell at Juan’s feet. He begged Juan to spare the tree, and Juan took the purse, shouldered his axe, and left.

He dropped in at the old widow’s hut by the road at nightfall, asked her to spread a mat, shook the purse over it, and out dropped bright pieces of gold. She went to buy cooked food at the market and they feasted and then he went to bed.

She woke him up early, gave him a purse that looked just like his purse, and wished him a pleasant journey home.

Juan’s mother was displeased to see that he had brought home no firewood. He told her to spread a mat, she did, and he shook the purse over it. Nothing dropped out, and she begged him to go and get her some firewood at last.

Juan hurried back to the woods and was just about to start whacking at the bangar tree when the kiba-an came down holding a rope, a whip, and a drum. He told the drum to beat, and it beat out a rhythm so urgent that Juan took it, the rope, and the whip and went on his way home.

He told the old widow in the hut by the road to prepare to hear wonderful music when he got to her hut. Then he told the drum to play, and it beat out a rhythm so compelling that she began dancing, but the rope tied her up and the whip beat her until she begged Juan to stop the drum and she would give him back his pot and his purse.

Juan did so, and never again had his mother any occasion to mention firewood.

SOURCE: Philippine Demonological Legends and Their Cultural Bearings, Maximo Ramos, Phoenix Publishing 1990

ALSO READ: The Merfolk of Philippine Folklore

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.