We discussed in the previous article that the egg motif the world over is generally linked with the symbolism not of birth, but of rebirth, or the repetition of the birth of the world at the moment of creation. We said too that the egg motif, either in myth or ritual, has definite connections with the symbols of the renovation either of nature or of vegetation as well as with the cult of the dead. Now Spring and the New Year in mythic thinking, are symbols of the first emergence of the world from chaos and unformed existence,or the great round before it becomes fragmented. In other words, the coming of Spring and the New Year themselves are symbolic of the eternal return to the state of chaos and the state of latencies or of seeds in the beginning. This return (according to archaic theory) can be effected either by an ekpyrosis, general conflagration, or by a cataclysm in the form of a universal deluge. This return to the original state is necessary in order to renew the exhausted forces and energies of the entire universe, and thus secure its continual existence. In this way, the eternal round of existence in cycles is secured. In this connection, the egg motif, whether on the cosmic or the human level, is a symbol not so much of birth, but of rebirth. Like the tree, the egg is also a symbol of nature and its continual renewal through death unto new life.

We mentioned that this renewal could be effected by a universal flood. A flood myth or deluge myth is a narrative in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval waters found in certain creation myths, as the flood waters are described as a measure for the cleansing of humanity, in preparation for rebirth. Most flood myths also contain a culture hero, who “represents the human craving for life”.

The flood myth motif is found among many cultures as seen in the Mesopotamian flood stories, Deucalion and Pyrrha in Greek mythology, the Genesis flood narrative, Pralaya in Hinduism, the Gun-Yu in Chinese mythology, Bergelmir in Norse mythology, in the lore of the K’iche’ and Maya peoples in Mesoamerica, the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa tribe of Native Americans in North America, the Muisca, and Cañari Confederation, in South America, and the Aboriginal tribes in southern Australia.

We will now look at flood myths among the Ifugaos and other pagan tribes of the Philippines.

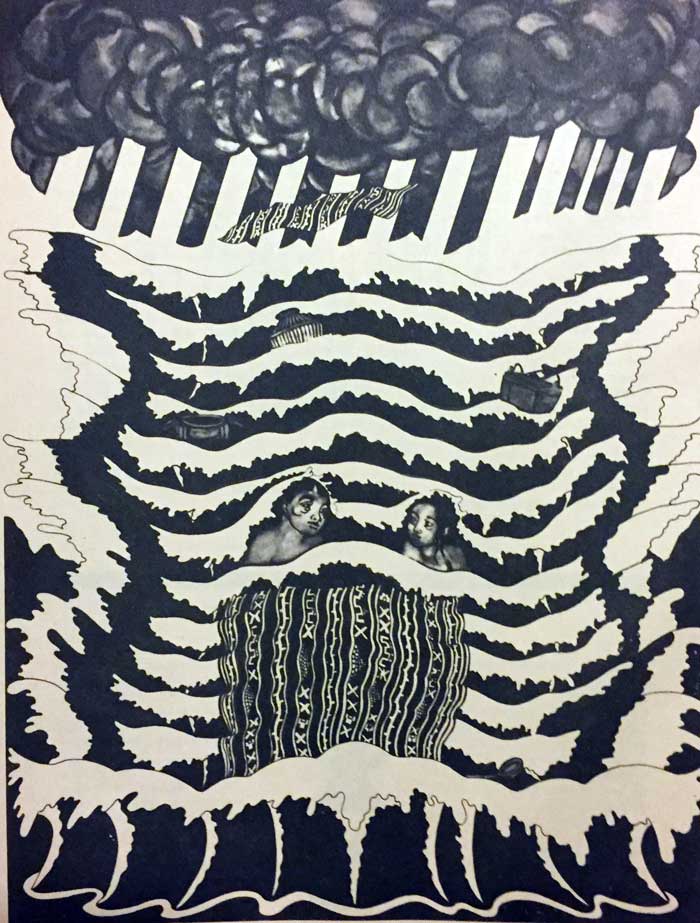

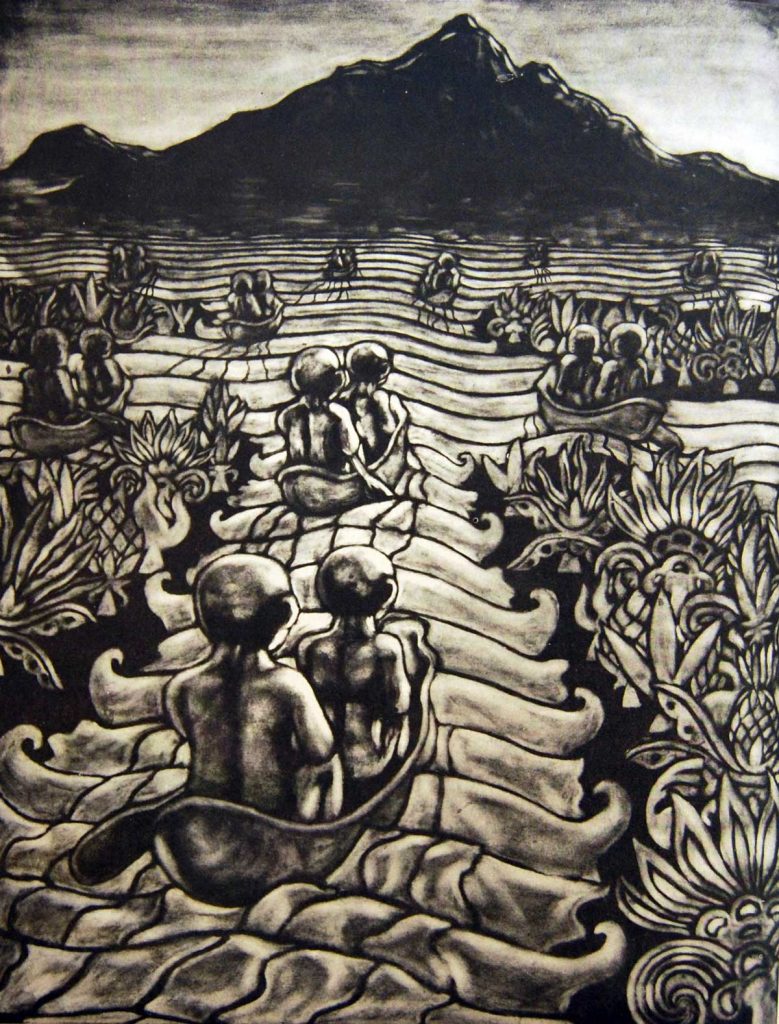

The Ifugaos tell of a great drought which dried up all the rivers. The old men suggested that they dig up the river which had sunk into its grave in order to find the soul of the river. For three days they dug when suddenly a great spring gushed forth. It came so fast that many died before they could get out of the pit. In their joy over the waters, the Ifugaos celebrated a feast. But while they were rejoicing, it grew dark; the rains fell, the rivers rose up so that the old men finally advised the people to run to the mountains for the river gods were angry. The people were all overtaken by the waters except two, Wigan and his sister, Bugan. Wigan was safely settled on top of Mt. Amuyao and Bugan, on the summit of Mt. Kalawitan. The waters continued to rise until the entire earth except the tops of the mountains was covered. For 6 months, the flood covered the earth. There was plenty of fruits and nuts on the mountain tops for the survivors. But only Bugan had fire. Wigan was cold because he had no fire.

The story goes on to tell how after the waters had receded, Wigan journeyed to Mt. Kalawitan and was reunited with his sister. They settled down the valley where the Banaual clan now live. Bugan realized one day that she was with child. In her shame, she left her home and followed the course of the river. Exhausted and faint after the long journey and consumed with grief, she sank to the ground only to be comforted by the appearance of the god Maknongan who came to her in the guise of a benign old man with a white beard. He assured her that her shame had no foundation. What she and Wigan had done was right because it was through them that the world would be repeopled.

In this synopsis it is clear that there was a belief among the Ifugaos in the successive existence of races of mankind: that the old race was wiped away by a flood, and that a new generation came into existence through the survivors of the flood. Rebirth is implicit in this flood myth.

Among the Ata we have this report from Cole:

“Long after this (the creation of the first male and female), the water covered the whole earth and all the Ata were drowned except two men and a woman. The waters carried them far away and they would have perished had not a large eagle come to their aid. This bird offered to carry them to their homes on its back. One man refused, but the other two accepted its help and returned to Mapula.”

Here again we see presupposed a new generation of Ata, sprang from the two remnants of the flood who were flown to their home by the bird. This tale also presupposes the existence of a previous race of men who perished during the cataclysm. The notion of the rebirth of mankind through the survivors helped by the bird is quite clear.

Among the Mandaya we have it reported that many generations ago, a great flood occurred which killed all the inhabitants of the world except one pregnant woman. She prayed that her child might be a boy. This was granted and the son who was born of her she called Uacatan. When full grown, he took his own mother to wife, and from their union came all the Mandaya. (Shades of the Oedipus complex).

*note: The Oedipus complex is a term used by Sigmund Freud in his theory of psychosexual stages of development to describe a child’s feelings of desire for his or her opposite-sex parent and jealousy and anger toward his or her same-sex parent.*

Again in this tale there are two things presupposed: the previous existence of a race of men now extinct on account of the flood, and the existence of a new race from the two survivors.

As for the Bisayan, one may not agree with Alzina when he says “Concerning the flood which they now call in their tongue ang paglunup sa calibutan (lit. ‘the inundation of the world’) that they knew nothing about it.” Fansler at least has a Bisayan story of a flood, supplied by Vicente L. Neri of Cagayan, Misamis, which he had heard from his grandmother. A flood took place on account of the quarrel between Bathala and the god of the sea, Dumagat. It seems that Bathala’s subjects, the crow and the dove, were stealing fish which were the subjects of Dumagat. He asked for retribution from Bathala and he got nothing. In vengeance he opened the big pipe through which the water of the world passes and flooded the dominion of Bathala until nearly all the people were drowned.

And Jose Maria Pavon tells a story of how the crow got its black color. The story in short goes this way:

In very remote times, God thought it good to send a great punishment to men. There followed a great internal war which took away the lives of many. Then a river overflowed its banks and took the lives of many more. The judge of the dead Aropayang, alarmed over the misfortune that had happened, sent out the crow and the dove to examine and count the dead. The dove came back and gave a faithful account of the disaster. The crow who came much later could not do so because it forgot to count the dead in its eagerness to peck at the eyes of the dead. Furious, Aropayang hurled a bottle of ink at the bird and thus stained the feather of the crow forever, and he cursed it to be lame on one foot where it was hit by the inkwell.

In these two tales, we have the motif of a flood if not of a universal deluge. The passing away of one generation of men who perished in the flood waters and the coming of another generation after the flood are at least hinted at. The followers of Bathala and the people in the Pavon tale were not altogether extinguished. So we can suppose that at least two or more survivors remained to repeople the world. And so, too, we can say that the notion of rebirth is implicit. In both stories again, there figure two birds, the crow and the dove. In these tales which are more folktale than myths, the birds do not lay eggs. But it is interesting how they are sent to count the dead. So it seems that the many motifs common to earlier myths of cosmic rebirth reappear in these tales: the flood, the survival of some people, the birds, the dead. The rebirth is not for the individual dead, however, but for the new race of men who will be born from the survivors to repeople the world.

Sources:

MYTHS & SYMBOLS, Philippines, Fr. Francisco Demetrio S.J., 1979

PHILIPPINE FOLK LITERATURE: The Myths, Damiana Eugenio, UP Press, 2001

The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao, Fay-Cooper Cole, FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY PUBLICATION 170, 1913

Historia de las islas e indios visayas, Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, 1688

Filipino Popular Tales, Dean S. Fansler, New York: American Folklore Society, 1921

Robertson Translations of the Pavon Manuscripts of 1838-1939

ALSO READ: The Egg Motif in Philippine Creation Myths

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.