The Philippines had always been a land steeped in deep spirituality. Any tourist would be amiss not to notice the magnificent Catholic churches sprawled throughout the predominantly Catholic islands. Brought by its Spanish Colonizers half a millennia ago, the Catholic Church has stood firm as a resilient pillar of Filipino society. The influence of the Catholic Church in the Filipino psyche could not be understated. Celebrations, folkways, norms, and mores – even those with more secular characteristics – have their roots (or reactions against) in the Church’s values. Three hundred and thirty-three years is perhaps more than enough time for the marriage of Spanish church and state to sit and root itself well deep in the Filipino psyche. Despite the influence of this monolithic institutional power, however, a fragment of a spiritual resistance remains – a faith that, in order for it to survive the Spanish ire, merged and syncretized itself with the power that had sought to dominate it; becoming a brand new faith with its own rituals, customs, and mythos in the process.

The influence of the Catholic Church wanes the moment one travels away from any city or municipal center. The physical edifice of the Church for example, becomes less and less prominent, and the capella, the chapel, and healing huts of the medicine men become more and more the focal point of community and spiritual gathering. The official versions of religion and myth changes the moment the stories move far from the center. The Jesus, Mary, and the Saints of the center transform and take in new meanings.

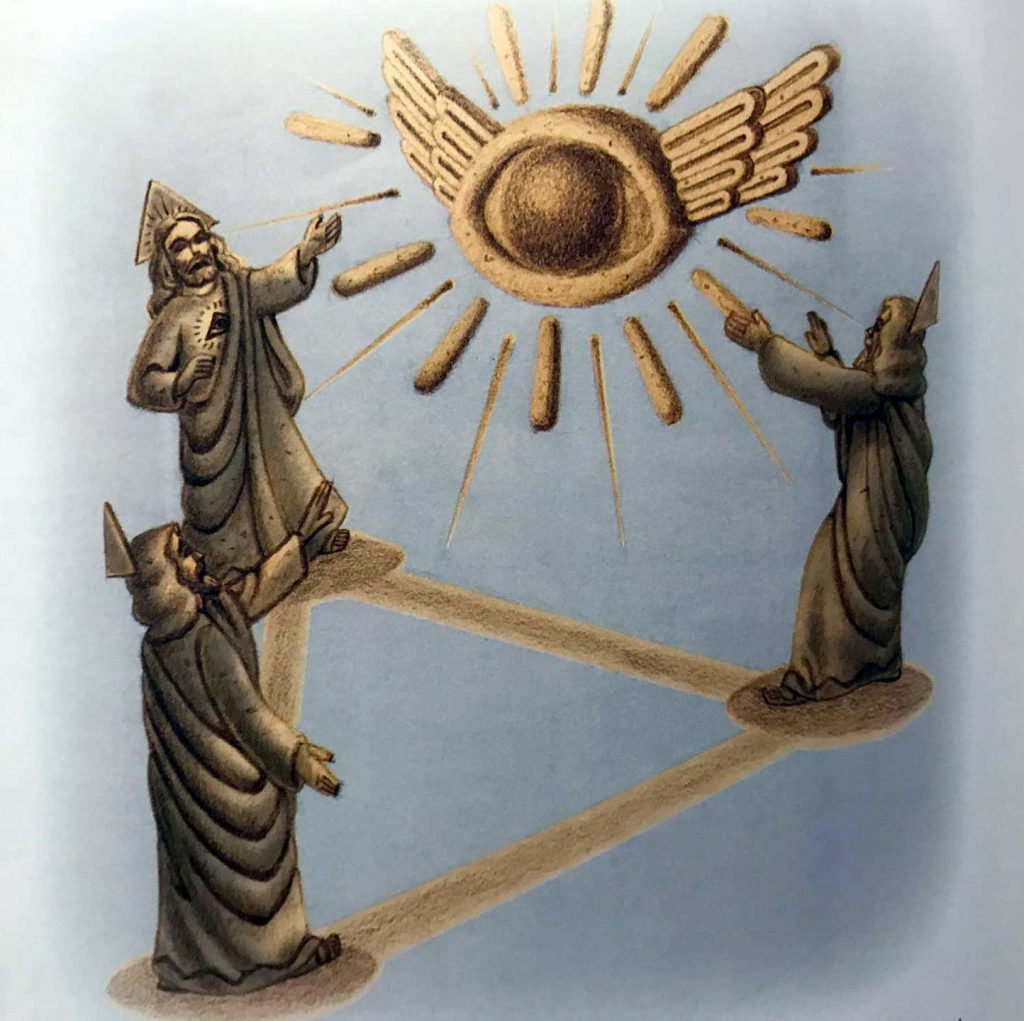

In areas where priests seldom travel to due distance or disinterest, religious life is advised by lay charismatic individuals who present themselves as medium-healers. These charismatic individuals are mounted either by saints – folk or canonized – or even by God himself; or those who wield mystical powers by virtue of powerful amulets known as anting-anting and perform miraculous feats with them, become community leaders in their own right. These individuals have followers who flock to them and through their experiences of the Numinous would transmit to their followers the hidden knowledge from the other realm; marrying or syncretizing the prevailing Catholic symbol set with the indigenous. Take an anecdote from the Katipunan. A revolutionary grassroots, peasant-led movement against the Spanish crown, the Katipunan had such leaders who incorporated traditional Filipino re-interpretations of Christianity. One such account is that of Andres Bonifacio, the founder of the movement, wherein he made preparations for the 1896 uprising by travelling to the cave of the folk hero, a quasi-messianic figure Bernardio Carpio who was has been imprisoned in Mt. Tapusi in the Holy Week of 1985. Carpio was believed to come again as the “Tagalog King” and free the land (Perkinson and Mendoza 129).

Stories such as that of Carpio are legendary at best, yet these legends and myths reveal that folk spirituality is spared from the dictates of theological baggage of the institutional church. These tales are organic expressions of a people’s experience with the divine. No intermediary was and is needed to dictate what is theologically orthodox and what is not. What makes this marriage of Indigenous Spirituality and Catholicism fascinating therefore, is that it is not advised by the dictates of any curate or parish priest rather that it draws from indigenous re-interpretations of the Christian mysteries syncretized with traditional religiosity.

Reynaldo Illeto’s Pasyon and Revolution discusses how the pasyon, the Filipino epic narrative on the passion of Jesus Christ, played a crucial role in the development of the Tagalog Folk Spirituality. In an age of scriptural readings read in either Latin or Spanish, as it was in the Spanish era, it is no surprise how the Tagalog pasyon becomes invaluable to the illiterate layman who wishes to know and understand his God.

From this milieu comes the myth of Impinito Dios. This myth is unique insofar as it is only relayed or known by a select number of people, i.e. members of esoteric groups. Most Tagalogs seem not to be familiar with it (Love 149). This essay will ground its analysis of the myth of Impinito Dios from a version of the myth that has risen out of a particular samahan: a Tagalog peasant religious group in the province of Majayjay, Laguna known as Ang Samahan ni Papa God.

The version of the myth comes to us from a member of the samahan, recorded in transcript by the cultural anthropologist Robert S. Love (Love 151 – 152). The myth is narrated by Ma Binong, a local curer who interrogates spirits (151). The theory of mimesis is used to interpret the myth.

The Myth of the Infinito Dios

…

Before our Beloved Lord (Jesus)…

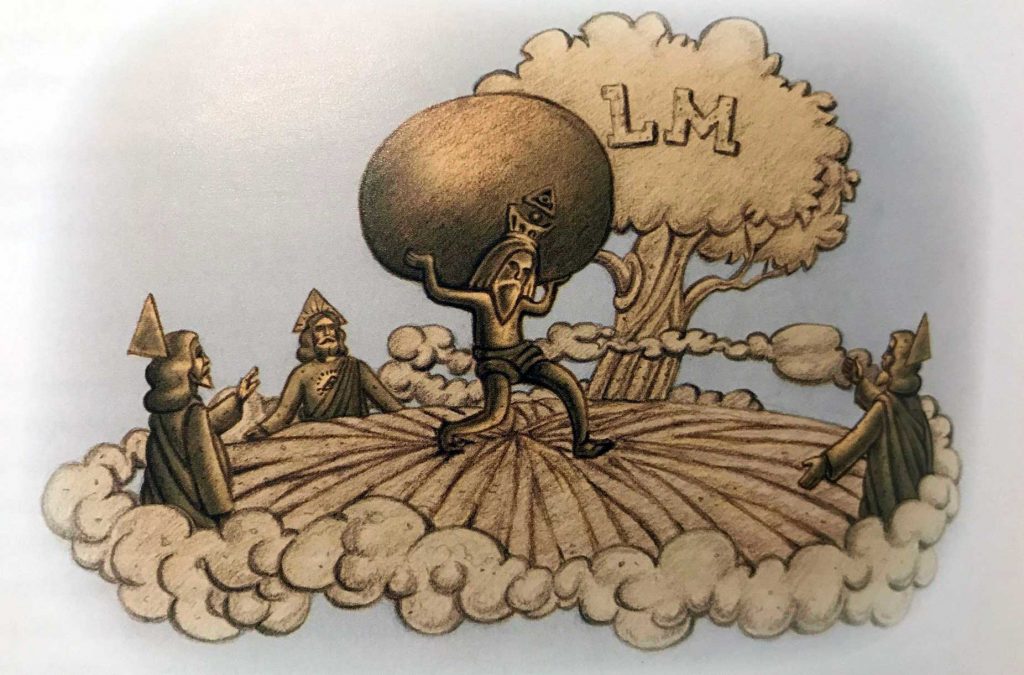

God (the Father) sent Jesus to earth, telling him, “You are God on the face of the earth.” When he came down to earth, what he saw was sea. Because he was God he was able to turn sea into earth/land (lupa). This he did by speaking, by speaking Latin. Now, since he was told by his Father that he was God on the face of the earth he was quite surprised to discover that he saw the traces (bakas) of another. He said, “I am God here. Why is it that something has left traces here before me?” So he said, “Whoever you are, I’ll give chase to you.” He then saw that which had left the trace, but from afar it was so unclear. He pursued it and when he went to touch it, it entered into a large stone. “Well,” he said, “this thing that I am chasing is really clever/able (magaling)!” “Who are you?”

Impinito Dios: “I am God, like you.”

Son (Jesus): “If you are God, come out.”

I.D.: “I will not come out”

Son: “Why did your say that I am God?”

I.D.: “Because I know that the reason you came down here on earth was to create. And you will reign here on earth. I am God like you, although I cannot show myself to you. And I am under your kapangyarihan.”

Son: “So that we can understand one another, come out of there.”

They tried to force one another till finally the voice in the stone said:

I.D. “Since you are trying to force me, bless this: my thumb.” (At this, he stuck his thumb out of the rock)

Son: “If that’s all, then all right I will bless / baptize it, but that means your whole body is affected (napadamay).”

I.D.: “Yes, I am indeed under your kapangyarihan.”

After baptizing it, Jesus covered the thumb and said, “From now on you are Impinito Dios, if God you are”

…

Ma Binong’s version of the myth of Impinito Dios presents a unique indigenous understanding about the creation of the world. Myth is not meant to be taken literally and must not be dismissed on account of their non-literal reality. Instead, myths carry with them the way a people people interprets their world symbolically (Jung 70). Building on the Catholic mythos, the natives found a way to reconcile a God of theirs from more ancient time to their new reality. For them, Impinito Dios had always existed. In short, he was God before God was. The monotheistic model as the belief central to the paradigm of orthodox Catholic Christianity is not problematic to the paradigm of a society steeped in animistic lore.

The baptism of Impinito Dios reflects a mythological re-telling of the Christianization and pacification of the Tagalog people. Villegas, a scholar of the anting-anting lore, makes the claim that the myth of Impinito Dios is allegorical to the resistance done by the natives against the encroachment of Spanish forces and their ultimate subjugation (Villegas qtd in De Guzman “The Hidden Myth”). The appearance of the Jesus can be read as symbolic of the Spanish foreigners who came arrive in these lands. The myth chronicles the syncreticism to keep the native faith alive despite the arrival of a newer pantheon (ibid).

When Jesus came down from heaven and started baptizing the things on Earth, he saw that there were existing bakas, traces about and was surprised to know that there had actually been an already existing God inhabiting the place. Allegorically, this might mean that there had always already been a people and a culture living here prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. The word bakas can be read to mean “trace” or “mark”. As Impinito Dios had been leaving his mark throughout the land in which he is God, undisturbed so to were the natives of yore.

The surprise and fascination in Jesus at the fact that there was already a God before his arrival might had been reflective of the Spaniards’ surprise that a quasi-monotheistic deity known as Bathala was worshipped. The myth claims that Jesus was impressed, saying that this being was “clever/able” (magaling). That is, impressed with this coincidence. Jesus chased him in order that he might baptize him, trying to make him subject to his authority. This attempt at baptizing Impinito Dios may be read as a psycho-history of the Spanish colonial practice of the reduccion, whereby the natives scattered in small villages were re-settled in a larger town and baptized en masse to Christianity symbolically (Russell “Christianity in the Philippines”). Baptism can be read as a ritual action of dominance and subjugation, for it is in baptism that a one is transformed from “barbarian” into “civilized” – from pagan into Christian. The myth is a subconscious record of those who went against the policy of the reduccion in the early phase of Spanish colonization. The people who resisted invasion went into further and further in-land (inside a rock, so to say) until they were finally pacified and baptized.

Impinito Dios hid in a rock because Jesus chased him. Eventually Jesus caught up and commanded him to go out the rock and reveal himself. It was there that Impinito Dios yielded, saying that he is under the power (kapangyarihan) of Jesus. As an act of submission, he showed his thumb and this Jesus baptized. Jesus said that by blessing the thumb, he has made all parts of Impinito Dios affected (napadamay). Jesus covered the thumb and made Impinito Dios God over this portion of creation. Having only thumb baptized signifies that though outwardly Impinito Dios may seem to appear a Christian – that is “civilized” – his being deep down come from a time before the arrival of any outsider. He may appear now as a subject of Jesus and his Father, yet his pedigree comes from somewhere timeless that history has not dared even record its existence. He looks Christian but he is older. One can noticed that only when creation happened was Impinito Dios was he limited into the annals of history. Impinito Dios had always walked on this part of the world. He had always been the God here. He had always been here. Jesus had to make it clear to him that even if it was his thumb that was baptized, the whole of him is affected. Interpreted, this could mean the adoption of the indigenous Impinito Dios into the Christian pantheon by being Christianized. He may have retained his Godhood but he has lost his supremacy. The covering or hiding of the thumb means that only those inducted into his mysteries truly know about him. He is covered and veiled: mysterious god and only those who have been initiated can understand that his eternality.

The myth of Impinito Dios demonstrates that the cultural history of a people can be traced re-traced within the oral narratives and the stories they tell and re-tell. Literature in this sense imitates life and in the case of the myth, carries with it a people’s social history. The story shows the resiliency of indigenous spirituality by opening itself to the arrival of a monolithic religious institution – the Catholic Church – and adapting becoming in effect a brand new tradition with its own narratives and its own world view.

The Filipino being, as with Impinito Dios, is and will always be eternally the same. Impinito Dios is the archetype of the indomitable Filipino spirit, a spirit that grows as it adapts with the passage of time and clime yet remains, deep down, essentially Filipino.

Works Cited:

De Guzman, Daniel. The Hidden Myth Behind the Symbolism of the Anting-Anting. The Aswang Project, 27 May 2018

Ileto, Reynaldo C., Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840 – 1910. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1979.

Jung, Carl Gustav, and Anthony Storr. The Essential Jung. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Love, Robert S. The Samahan of Papa God: Tradition and Conversion in a Tagalog Peasant Religious Movement. Manila: Anvil Publishing, Inc, 2004.

Perkinson, Jim, and S. L. Mendoza. Indigenous Filipino Pasyon Defying Colonial euro-reason. Journal of Third World Studies, vol. 21, no. 1, 2004, pp. 117-137. ProQuest

Russell, Sussan. Christianity in the Philippines. Christianity in the Philippines

ALSO READ: PHILIPPINE RELIGION: A Curious Thing Happened on the Way to Christianization