Anting – Antings in plain sight are medallions created from pieces of metal or wood. With a much closer look, you may be curiously struck by the symbols and words inscribed on it, that appear to be a mishmash of Latin and riddles. If you widen your perceptions and slightly lower your walls of cynicism, you will find the most alluring tales surrounding these mystical items. Legends and folk tales about these items giving super human strength abound.

Yet more than the promise of brute strength, invisibility, bullet and blade proof skin, there is an underlying connection between the ancient beliefs of Filipinos and their current faith today. They also serve as an allegory to the arrival of the Spaniards and how the old deities of our ancestors became absorbed into a monotheistic religion.

All of these are found right in the deepest history and cabals of the Anting – Anting.

A Much Older Version

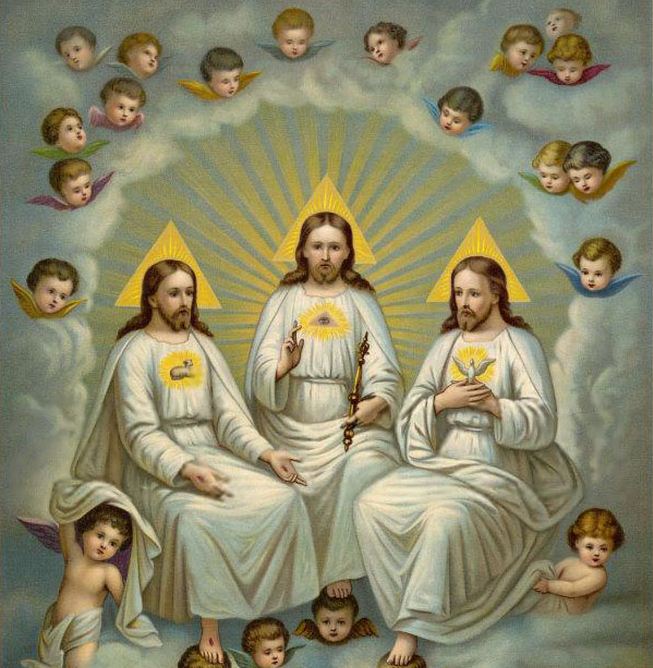

I used to believe that the Anting-Anting was a Filipino way of expressing Catholic faith through esoteric and mystical practices. Looking into the symbols used by Anting-Anting makers, one can find a lot of references to Christian lore, the All Seeing Eye, St. Michael the Archangel, and the Holy Trinity (Santisima Trinidad). My previous views were changed after I learned a few things about our ancestor’s earlier versions of the Anting-Anting.

Pre-colonial Filipino beliefs in objects and items holding a spiritual or magical power, like the Anting – Anting, is reflective of our nation’s oldest religion, which is animism – which is the attribution of a soul to plants, inanimate objects, and natural phenomena. Like our myths and lore, the manifestation of this belief varies between ethnic tribes. Among these is the Ilocano’s mysterious stone called babato or ginginamul which is said to give unimaginable powers to those who acquire it – usually by means of a revelation of certain spirits or anitos or being passed down from generation to generation.

The lingling-o is an accessory of the Ifugao, which can be in a form of a pendant or earrings and is said to grant men an enhanced virility or boost the fertility of a woman. This kind of accessory was not only found among the Ifugao, but also in Tabon caves of Palawan.

From the documents collected in the Boxer Codex, the natives of the Philippine consider the following amulets to provide them various powers and enhancements such as long life, protection against sickness, and to ward off wild animals. The older anting antings were said to contain man-shaped stones, hair of the ‘duwende’, different herbs, seeds and roots, or a tooth of a crocodile.

One of the clearest indications of our ancestor’s belief in the powers residing in non-living and mundane things is the Bul-ol or Bulul. Among the tribes of Northern Luzon, these are small wooden statues that resemble the likeness of a man wherein they believe their Anitos (spirits) and are tied into general well being and successful harvests.

This evidence give us an indication that even before the current image of the Anting-Anting with traces of Catholic symbolism, our ancestors were known to have a great belief in magical or spiritual objects that bestow powers and miracles. The difference is that before the Spaniards came, these objects of powers were heavily rooted in animist practices.

The coming of Ferdinand Magellan, together with other conquistadors, resulted in a great shift for the spirituality of the archipelago’s residents which eventually affected our conception of the Anting-Anting.

From Anitos To Santos

The pantheons of gods in the Philippines during the pre-hispanic age is akin to Greeks when it comes to diversity. Every deity, diwata, or anito were attributed to various elements, functions or favors. In many cases, these deities were in a pantheon under a supreme creator. Many ask why our ancestors easily embraced Catholicism despite the fact they were polytheist and had a strong attachment to it. Dennis Santos Villegas, author of “You Shall Be As Gods” theorized that the natives saw the religion brought by the conquistadors similarly to their own religion, such as the numerous amount of rituals. Moreover, it seems the anitos and diwatas shared a similarity with the angels and saints introduced by the Spaniards, wherein each of them also had a different set of tasks and roles to play – like healing for the sick, harvest and religion. To some, the supreme creator may have held little difference to the Christian God.

We don’t know with certainty why Catholic beliefs were, at times, easily adopted. Perhaps it was the attractiveness of some images, props and icons such as the statuettes of the Sto. Nino. According to Antonio Pigafetta, chronicler of Magellan’s journey, the Queen of Cebu (King Humabon’s wife) was so greatly entranced by the beautiful appearance of the image of Sto. Nino that she was “overcome with contrition and asked for baptism amidst her tears.”

Pigafetta noticed this “and recommended her to put it in the place of her idols.” This example may be an indication for how other natives abandoned their old idols in honor of the new religion they were now subjected to. That said, it is also no secret that Legazpi and his colonizers were aggressive about conversion and left the natives little choice. A petition (probably written in 1566), signed by the Spanish officials in the Philippines, asked for more priests there, more soldiers and muskets to assist in this process. “More men, and arms and ammunition for five or six hundred men, so that if the natives will not be converted otherwise, they may be compelled to it by force of arms.” – 1565-1567. Relation of occurrences in the Philippines after the departure of the “San Pedro” to New Spain.

Once anitos were replaced by images of Saints and Angels, one could incorrectly surmise that our ancient belief was completely eradicated. When speaking about the time Catholicism started spreading to all corners of our nation, John Leddy Phelan (“The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aim and Filipino Responses”) states that “the densely populated spirit world of pre-Hispanic Philippine religion was not swept away by the advent of Christianity. Some Filipino Catholics continued to ask permission from spirits before doing certain things.”

The ancient animist beliefs of our ancestors were not completely destroyed, but rather absorbed into a new religion that bore a striking moral similarity. Eventually this also influenced the cabals and lore behind the Anting-Anting which delved deeper and deeper into an esoteric practice mixed with the ideas and concepts of Christianity. Villegas indicates that the fusion of the Christian God to the ancient god Bathala formed a brand new deity called Infinito Dios (Infinite God) which has its own mythology and origin.

Hidden Mythology of the Anting-Anting

An obscure but highly valuable book about the Anting-Anting called “Karunungan ng Dios” by Melencio Taylo Sabino depicts the genesis of Infinito Dios and the so called “combate spiritual” (Spiritual Combat) between him and the Santisima Trinidad (Holy Trinity). The book itself narrates that the sole creator of the world was Infinito Dios, the Animasola (Lonely Soul), which is described in the translation of Villegas from the original Filipino text to English as “a winged eye wrapped in a shawl who forever changed his form while floating in infinite space.”

The story says that the Santisima Trinidad found a ball of light where a mysterious voice came forth. They decided to baptize it without knowing that it was the Infinito Dios. As they approached, it quickly changed its form into a winged eye, beginning the combate spiritual.

The Santisima Trinidad were surprised to see the Infinito Dios for they believed that they were the lone creators of the universe and that this being must be baptized. However, Infinito Dios refused, knowing the he is the one who created everything – including the Santisima Trinidad, so he fought and escaped the Santisima Trinidad via different oraciones. Both parties exchanged eldritch phrases that paralyzed, blinded and confused the other. The Santisisma Trinidad begged the Infinito Dios to let himself be baptized and promised many things in heaven and on earth.

In the end, the Ininito Dios decided to be baptized on the condition that he will be baptized only by his name which is MACMAMITAM MAEMPOMAEM.

Although the above mentioned tale is an example of an alternative mythology that has never been recognized by mainstream belief, we can see that it has a somewhat allegorical tone that explains the coming of the Spaniards with their Christian God encountering the deity of our ancestors. The theme of baptism had a very strong connection to the desires of the Spaniards to evangelize and indoctrinate the natives in the name of the Holy Trinity as one God. Villegas explains further that the myth of Infinito Dios alludes to our ancestor’s resistance against Catholicism replacing their old animistic religion.

The myth, as Villegas further analyzed, emphasizes that “Bathala/Infinito retained his own name, power and authority in Philippine religion despite the encroachment of the Santisima Trinidad on the native faith.”

He added that the myth of Infinito Dios “saved the originary paganism from being completely eradicated by Christianity.”

Quenching a Spiritual Thirst

I’ve been digging around for some time about any recorded documents or writings about esoteric and magical practices performed by our ancestor before the beginning of colonization. Besides the rituals of the Babaylan, which are more or less inclined to shamanism, I find myself directed to the Anting – Anting. The work of Dennis Santos Villegas profoundly affected me with the exploration of the mysticism behind the Anting – Anting and it helped me understand how deeply rooted it is in our ancient beliefs.

I don’t possess any Anting – Antings, nor can prove to anyone its potency – or whether it can save you from multiple slashes from a bolo knife). If there is one thing we can try to ponder regarding the verity of these items, and even in the lore that surrounding them, it’s the thirst that the Filipinos are secretly trying to satisfy against the transition of faith they experience: a spiritual desire to be connected with something or someone beyond human faculties. Filipinos are known to be spiritual all over the world, but somehow it makes me ask myself if being spiritual means always to be dependent on your religion.

Maybe, whether you are Animist, Pagan, Christian, Muslim, a combination of the four, or none of the above, you can always be spiritual. The simple existence of the Anting – Anting gives me proof that whether you are a believer or a non- believer, you will find a way to get closer to your ‘god’.

ALSO READ: ANTING-ANTING, the Filipino “amulet” or “charm”

Currently collecting books (fiction and non-fiction) involving Philippine mythology and folklore. His favorite lower mythological creature is the Bakunawa because he too is curious what the moon or sun taste like.