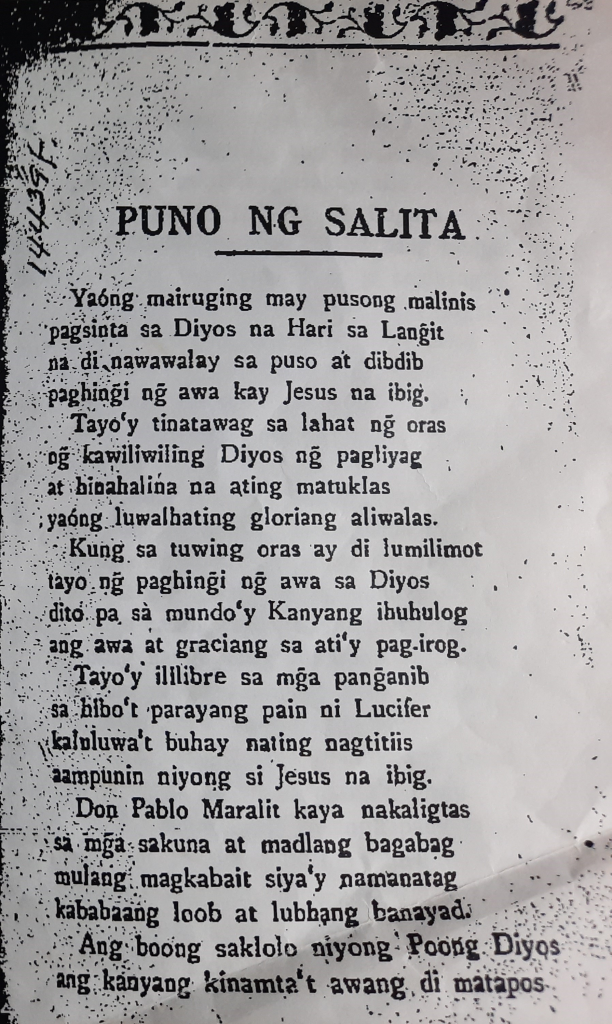

In the last post, I talked about the legend of Pablo Maralit. In this post I want to talk about another account of Pablo’s legend, one that is not in prose but rather in verse. In other words, it is an awit or metrical romance. There are supposedly two awits written about Pablo Maralit. According to Gabriel Bernardo, the first was published in 1922 by a certain Nemesio Magboo from Malabon (1). The title of the awit is Buhay ni Dn. Pablo Maralit; tubo at nagtatag ñg Bayan ng Lipa at nabantog sa catapangan at nagpasuco sa mga encanto” (Life of Don Pablo Maralit; native and founder of the town of Lipa, made famous for his bravery, and who defeated the encantos). Unfortunately, I have not been able to find a copy of this awit. It is not in the catalog of the Philippine elib nor in Damiana Eugenio’s master list of awits (2). Bernardo claims to have it in his collection although that could have been destroyed during World War two.

What survives is the second awit published in 1924 (3). This is a continuation of the first one and also authored by Magboo. Its title is Kalugod-lugod na buhay ni Dn. Pablo Maralit: mula sa pagpapagawa ng kaniyang bahay hanggang sa siya ay maging kapitan (The most happy life of Don Pablo Maralit: from the building of his house until he became captain). Although it is a continuation, this awit can easily be understood if one knows the background of the Pablo Maralit legend. So I advice the reader to review my previous post before proceeding below to the summary of the awit. After the summary, I will give some of my personal remarks.

Ang Kalugod-lugod na Buhay ni Don Pablo Maralit

The awit begins with Don Pablo and Doña Catalina already married. They decide to have their own house and Pablo asks his master-builder friend from Taal to build it. The master-builder with his nine apprentices leave for Lipa but while on Bombon lake (Taal lake) a storm sinks their ship. They survive and return home, but their equipment is lost. When Pablo hears this, he takes pity and visits them. Upon arriving, the master-builder and his apprentices welcome him joyfully. The master-builder’s wife Federica and the wives of the apprentices travel to Lipa to invite Catalina for dinner. Catalina agrees and brings along her and Pablo’s parents. They (including Pablo) then stay for an additional five days in the master-builder’s home. After this, the guests leave but not before Pablo invites everybody to his own home. The latter agree and soon Pablo hosts his own feast inviting the other people of Lipa, rich and poor alike. While this is happening, Pablo sneaks out and goes to Bombon lake to call his sirena friend. When she arrives, he requests her to get the sunken equipment of the master-builder. The sirena complies and Pablo thanks her. After this, Pablo calls on an engkanto in the form of an old man from Indulanin (one of the peaks of Mount Maculot) and asks his help to bring the equipment to his house. The latter complies and, surely enough, when Pablo returns home the equipment is already there. Pablo thanks the old man and invites him to his house. The engkanto refuses and says that instead his three other engkanto friends will arrive tomorrow. When morning comes, the three engkanto are there and play music much to the delight of Pablo’s guests—although the guests cannot see them. Pablo then shows the master-builder his lost equipment. The master-builder is overjoyed but also curious as to how his equipment could have been saved. Pablo just tells him to give God thanks by going to Mass the next morning. The master-builder does so along with Federica and the apprentices. After the Mass they are surprised to see a table of bread, chocolate, and other food, prepared for them by the three engkanto. Upon finishing breakfast, ten beautiful and swift carriages park in front of them. What is magical about the carriages is that they aren’t being pulled by anything. Pablo then arrives and tells the party that these will take them to their homes.

After this, the master builder and his apprentices begin to build Pablo’s house. It takes six months. When they finish, Pablo invites them to come for the house blessing. Pablo and Catalina also invite Federica and the spouses of the apprentices. These are then fetched from their homes by the magic carriages. Pablo further invites his engkanto friend from Indulanin and the latter accepts, telling him that the other three engkantos will also be there. Pablo and Catalina then go to the parish priest and ask him if he could bless their new house. The priest graciously agrees, saying how he is still thankful to Pablo for ridding the town of a dangerous specter (multo). The next day, the priest says Mass and Pablo, Catalina, and their guests attend. As the priest consecrates the host, several fireworks shoot up and burst into many colors. This is the work of the engkantos who also participate in the Mass. After the Mass, they all go to Pablo’s new house and everyone is amazed by its remarkable beauty; its curtains were all alpombra (expensive Moroccan textile) and throughout the house were decorative hangings of different colors—red, yellow, green, and black. In the living room, a variety of delicious food was spread on the table. These too were the work of the engkantos. After the guests dine, the priest and his acolytes proceed to bless the house while being accompanied by music. After the blessing, all the guests including the priests and acolytes are served dinner. They are then returned to their homes by the magic carriages.

After some time, Pablo decides to sell cattle in Manila. Catalina warns him that the road to Manila is infested by bandits. However, Pablo reassures her that God would protect him and he will always pray. For a time, all goes well. The couple’s income increases but they always remain humble and grateful to God. One day, cattle dealers from Taal ask if they could join Pablo in his trip since they heard that he was always safe on the road. Pablo kindly agrees to their request. However while on their way back from Manila they are held up by bandits. Unfortunately, Pablo’s talismans suddenly fail him and so the group is helplessly robbed. As they return home, they could do nothing but weep over their mishap. The Taaleños are especially dispirited since they could no longer pay their clients. Pablo comforts them by offering to pay what they owe, and also by offering them his house where they could rest and stay the night. When they arrive, Pablo tells Catalina about the ordeal. Catalina weeps but Pablo tells her not to worry and asks her to prepare food since several friends will come over the next morning. Specifically, Pablo tells her to prepare two pigs as well as maliputo and muslo (4). The next day the bandits arrive at Pablo’s house. Their leader, a certain Pedro Zalasar from Muntinlupa, speaks to Pablo and apologizes for what his men have done. He then returns the things they stole, and tells Pablo that he is willing to accept any punishment. Pablo however tells Pedro to forget about it and invites him and his men to dine in his house. Everyone then feasts on the food that Catalina had prepared. Out of gratitude, the bandits promise that they will never steal again, and that they will be ever ready to help Pablo. Pablo thanks them and also promises them the same fellowship. The (former) bandits and the Taaleños then depart, grateful for Pablo’s kindness.

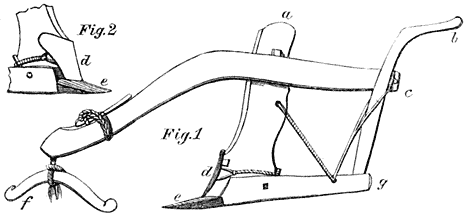

Pablo’s fame eventually reaches three Spaniards who have “anting-anting” that make them invulnerable to blades. These three, namely, Don Diego Banta, Don Prudencio Alix, and Don Leoncio Cuevas, decide to go the Philippines to test Pablo. They first arrive in Manila where they hire an interpreter and then they go to Lipa. Arriving at his house, they see Pablo fixing his araro (plow) in the silong (cellar) of his house. The interpreter asks where Pablo is, but Pablo responds by saying that the owner of the house is currently away, although he will arrive shortly. While waiting, the Spaniards take metal parts of Pablo’s plow, namely the sodsor (sudsod) and lipia (5), and eat them. At seeing this, Pablo goes up to Catalina and tells her to prepare food. He then invites the visitors to dine. At the dining table, Pablo and Catalina personally hand utensils to the guests. To the Spaniards’ surprise however, their spoons cannot scoop any rice. Neither could they do anything with the food using their forks and knives. Even when they could pick up the bread with their hands, they could neither break nor bite it. Surprisingly, the interpreter accompanying them could easily get and eat these same foods. Pablo then tells the Spaniards that he thought they were very hungry, seeing that they ate the parts of his plow. Now however, they don’t seem to like what was served. Out of shame, the three leap from a high window. Pablo then asks the interpreter to invite them back and to tell them that he is indeed the Pablo that they were looking for, and that he is at their service. When the Spaniards return, they are finally able to eat. They apologize to Pablo and tell him that they came to his place to get to know and test him. However, based on what they have seen, they judge him to be good of heart. In truth however, the Spaniards also came to fear Pablo and they realized that they are no match for him. At any rate, Pablo and Catalina continue to show the Spaniards their characteristic good-will.

Now during that time smoke began to rise from the mouth of Pulo’s volcano (Taal Volcano) in the middle of Bombon lake. Struck by curiosity, the three Spaniards wished to visit it. Pablo helps them despite having no desire to go. He hires a boat and they all go towards Pulo. On the way, they spot someone riding a horse in the middle of the lake, travelling towards Mount Maculot. The rider is splendidly attired in gold and his horse is remarkably swift. Suddenly, the sky darkens and a storm batters the boat. Everyone is filled with fear except Pablo who chases the rider by running on the surface of the lake. The rider is actually an engkanto friend of Pablo (perhaps the old man from Indulanin). They return to the boat and when they arrive, the storm ceases. The engkanto tells the people in the boat that he is the ruler of Pulo. He says that he was aware of their coming because Pablo told him through a telephone call (yes, really!), and that the reason he was going to Maculot was that he wanted to invite his three other engkanto friends from Indulanin to welcome them. He further explains that the storm that just appeared was actually just Pablo and himself greeting each other. He then accompanies them to Pulo. When they arrive they are fetched by the three aforesaid engkanto, riding magic carriages. They take an underground path that leads to the engkanto’s dwelling somewhere west of the island. The dwelling is truly beautiful having gold and tumbaga statues, chairs, and floors. When dinner time comes, a table filled with food suddenly appears and the people have their fill. The next day they head for the crater. The engkantos put lana (oil) on the feet of Pablo and the Spaniards to prevent them from being burned by the heat. They reach the top of the crater where they see the simmering lake inside. Pablo and Prudencio then decide to dive beneath the lake. Under the water they see a leafy tree that is guarded by a lion. When they approach the tree, the lion turns into a person and greets them. The person gives them a branch of the tree which serves as an effective remedy for diseases. They then emerge from the lake and, after some sight-seeing, the party goes back to the engkanto’s dwelling and ultimately to Pablo’s house.

Eventually, the Spaniards decide to return to Spain. Pablo accompanies them to Manila to see them off. There they meet with the Captain-General of the Philippines. After some pleasantries, the Captain-General takes them to the beach where a ship has been stuck for a couple of days. He says that his workers have done everything they could to launch the ship but to no avail. Pablo volunteers to move the ship, and says that he will be able to do it by tomorrow without anyone’s help. The Captain-General agrees telling Pablo that he will get a reward if he succeeds, but also a punishment should he fail. Later that night, Pablo calls the old man from Indulanin and requests his help. The old man assures him, and calls the three engkantos to help Pablo move the ship. By eleven in the evening the three engkantos start moving the ship, and by three in the morning the ship is free from the shoal. When the sun rises, the workers gather on the beach and are amazed to see that the ship is already floating in deep waters. Soon, the Captain-General hears of the news and takes Pablo to his palace to celebrate. He then asks Pablo what prize he would have. Pablo replies that he doesn’t want anything, and that he considers it his duty to serve. Impressed by his sincerity, the Captain-General tells him that he will be gobernadorcillo of Lipa. He has a set of clothes and a staff made for Pablo’s new position. He then sends a letter to the parish priest of Lipa telling him to urge the nobles of the town to elect Pablo as their Capitan. This happens easily since the town owes Pablo a great debt. When Pablo returns he is welcomed by music and fanfare. The drums are also played to signal that the town’s leader has arrived. He is then brought to the tribunal where he is installed as Capitan. Then he retires to his home accompanied by the town’s nobles who continue to play music and make merry. During his term, Pablo transfers Lipa away from Bombon lake and into its present area due to the danger of Pulo’s volcano. The awit ends by saying that Pablo and Catalina spent the rest of their days in peace and being pleasing to God.

Remarks

My remarks will be about the differences between the awit and prose versions of the legend. One difference is that in the awit Pablo’s powers mainly come from the engkantos while in the prose versions it comes from his anting-anting. In the prose versions there is not even mention of engkantos, while in the awit Pablo’s anting-anting are only barely referred to. Maybe the reason for the latter is that most of the “action” that has to do with anting-anting is in the first awit which, again, I unfortunately could not find. This might also be the reason why there is a lack of “combat” in this second awit—all of the fighting might have happened in the first awit where Pablo was precisely “defeating the encantos” (6). Instead of fighting, what often happens in this second awit is eating or feasting. This might seem strange but it is actually a common element of Philippine epics. Epic heroes often show their wealth and magnanimity by hosting feasts—even inviting their enemies to it (7). Another difference is that in the prose versions, Pablo is challenged by Moros while in the awit he is challenged by Spaniards. Perhaps Magboo, due to a sense of nationalism, didn’t want to put Moros in a bad light considering that they too are Filipinos. Finally, the awit has a more religious tone than the prose versions. Pablo and Catalina are portrayed as being very pious Catholics and their attitudes are portrayed as examples to be followed. Again, this might be Magboo’s own doing since he has written a number of other religious awits, as this link to some of his digitized works show. However, it is interesting to note that in Africa’s account of the Pablo Maralit legend, there is one scene where the old man from mount Maculot tells Pablo to cultivate humility and love for God after giving Pablo his talisman. So there might still be a religious theme in the oral versions of the legend. After all, folk literature can function as a medium to impart moral and spiritual values.

Conclusion

According to E. Arsenio Manuel, a Philippine folk epic must be a “(a) narratives of sustained length, (b) based on oral tradition, (c) revolving around supernatural events or heroic deeds, (d) in the form of verse, (e) which is either chanted or sung, (f) with a certain seriousness of purpose, embodying or validating the beliefs, customs, ideals, or life-values of the people (8).” I believe that this awit fulfills most of these conditions. The awit is quite long, being more than 2,000 lines. This makes it lengthier than some epics like Lam-ang (9). The awit is also based on oral tradition since it is inspired by the legends of Pablo Maralit. It likewise evidently revolves around supernatural events or heroic deeds. And as just discussed above, the awit relays values that reflects the culture of the people who made it (i.e., the Christianized Tagalogs). The only condition the awit doesn’t fulfill is “e.” Although awits in general could be sung, there is no sure information telling us if this specific awit was sung/chanted (10). But the same case applies to the Ibalong because it is uncertain whether it was a translation of an original epic, or if it was Fr. Melendreras’ own creation based on existing Bicol folklore (11). And yet Ibalong is generally considered a Philippine epic. In light of this, then perhaps it is possible to consider the awit of Pablo Maralit as an epic. And maybe Pablo himelf can be considered an epic hero of the Tagalogs, taking his place among the ranks of Filipino epic heroes like Lam-ang and Bantugan. Anyway, that’s just food for thought.

Footnotes:

(1) Gabriel Adriano Bernardo, A Critical and Annotated Bibliography of Philippine, Indonesian and Other Malayan Folk-lore. (Cagayan de Oro: Xavier University Press, 1972), p. 48.

(2) For Philippine elib see link. Damiana Eugenio’s master list of Philippine metrical romances is in her book: Damiana Eugenio, Awit and Corrido: Philippine Metrical Romances. (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1987).

(3) Entry of the work in Philippine elib. Nemesio Magboo, Kalugod-lugod na buhay ni Dn. Pablo Maralit mula sa pagpapagawa ng kaniyang bahay hanggang sa siya ay maging kapitan. (Manila: Limbagan at Aklatan ni P. Sayo balo ni Soriano, 1924).

(4) Maliputo and muslo are fish that inhabit Pansipit river and Taal lake. They are well-known delicacies in Batangas, although there is confusion if they are the same or different fish. See this link from “Batangas History, Culture & Foklore.”

(5) Sudsod is a metal part of a plow that unearths the soil. The lipia is another metal part above the sudsod that moves the unearthed soil to the side.

(6) Bernardo does imply that the first awit is similar to Africa’s account. See: A Critical and Annotated Bibliography of Philippine, Indonesian and Other Malayan Folk-lore. (Cagayan de Oro: Xavier University Press, 1972), p. 48.

(7) See: Literature of Voice: Epics in the Philippines. Edited by Nicole Revel. (Quezon City: Ateneo De Manila University Press, 2005), p. 14.

(8). E. Arsenio Manuel, “A Survey of Philippine Folk Epics,” Asian Folklore Studies, 22 (1963): p.3.

(9). The first version of Lam-ang has 977 lines. See: Damiana L. Eugenio. Philippine Folk Literature: The Epics. (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2001), pp. 3-21.

(10). On awits being sung see: Gabriel Adriano Bernardo. Pinagdaanang Buhay ni Florante at ni Laura (Manila, Philipines Writer’s League, 1941), p.3.

(11). For an opinion on this issue see: Florentino H. Hornedo, “Fr. Bernardino Melendreras, OFM (1815-1867),” Philippine Studies, 32, no. 4 (1984), p. 526-528.

ALSO READ: The Legend of Pablo Maralit, Hero of Batangas: Part 1

I finished an undergraduate and master’s degree in Philosophy. But one of my continuing interests is Philippine folklore and mythology.