When exploring the folktales of different Filipino ethnic groups, one often finds epic heroes that are remembered for their great deeds such as the brave Lam-ang of the Ilocanos, and the wise Handiong of the Bicolanos. In the folklore of the Batangueño Tagalogs there is also one who might be likened to an epic hero, namely, Pablo Maralit of Lipa. Like other Filipino epic heroes, Pablo displayed magical powers and fantastic feats. His stories also contain elements similar to the quests of Filipino epic heroes, such as winning a spouse, battling monsters, and defending his people. Below I will discuss the prose accounts of his legend and then give some of my personal remarks.

The Legend

Probably the earliest reference to Pablo Maralit’s legend is by Wenceslao Retana in his book El Indio Batangueño published in 1888. There he briefly mentions that the people of Lipa have an “absurd” belief that they once had a gobernadorcillo named Pablo Maralit who could walk on the bottom and surface of Bombon Lake (Taal lake) (1).

The next reference is from Teodoro M. Kalaw who mentions Pablo in the book Bajo los Coceteros (Under the Coconut Trees), published in 1911. In it, Kalaw writes of the picturesque beauty of Bombon Lake and how it evokes memories of legendary figures that used to lived there such as Pablo Maralit who “went through on foot, without sinking, from coast to coast, to prostrate at the feet of Capitana Catalina, the owner of his heart (2).” In another book, Cinco reglas de nuestra moral antigua: una interpretación (Five preceptives from our ancient morality : an interpretation), which was published in 1935, Kalaw also gives a passing account of Pablo’s legend (3). He says that Pablo Maralit was the gobernadorcillo of Lipa in 1714. In his youth, he became the leader of the young men of the town who were tasked with moving the church and the convent of Lipa to its present location. This is because the Lipa that Pablo lived in was actually at an older site than present day Lipa (more on that later). Anyway, Pablo’s counterpart in this task was “Doña” Catalina, who led the young women. Catalina said that she would take as a husband only one who was brave. It was for this reason that she married Pablo, for he had shown great courage in fighting serpents, monsters, and bandits among other things. His fame for his feats was so widespread that it reached the Igorots and the Joloanos. There was also a time when Pablo was thrown down a deep well on mount Maculot. Such was his fall that his companions thought he was dead. However, on the ninth day of his “passing” he amazed everyone when he returned to Lipa by walking on the surface of Bombon lake.

A thicker account of Pablo’s legend comes from Leon B. Meer who documented a number of folktales from Batangas in 1916 (4). One of the stories that Meer collected was a tale about a “Don Pablo” who was the king of Taal volcano. According to the story, Don Pablo lived in the crater of Taal volcano and he possessed several talismans (anting-anting) that made him famous throughout the Philippines. One day three Moros came to his home to challenge him. When they arrived, Pablo was resting under a mango tree and they mistook him for his servant. The Moros showed him their powers anyway. One of them jumped over Pablo’s house, the other took a large iron rod and split it into two equal parts with his bare hands, while the last took a plowshare and chewed on it. Pablo however was unfazed. He invited them to his house and told his wife to prepare dinner for them. The Moros were first given a big serving of rice with the burnt part (tutong) on top. The Moros tried to separate the tutong with their spoons but try as they might, they could not. They then realized that this was due to the magic power of Pablo’s servant. They began to fear that if they could not overcome him, then all the more will they be helpless against Pablo. Pablo then gave them a sugar cane stalk to divide among themselves. However the Moros found that they could not do so. Finally, Pablo led them outside the house and asked them to jump over a two feet high mortar. Again the Moros failed. Feeling much shame, they bid farewell to Pablo who in turn revealed himself as the one they were looking for, the king of Taal volcano.

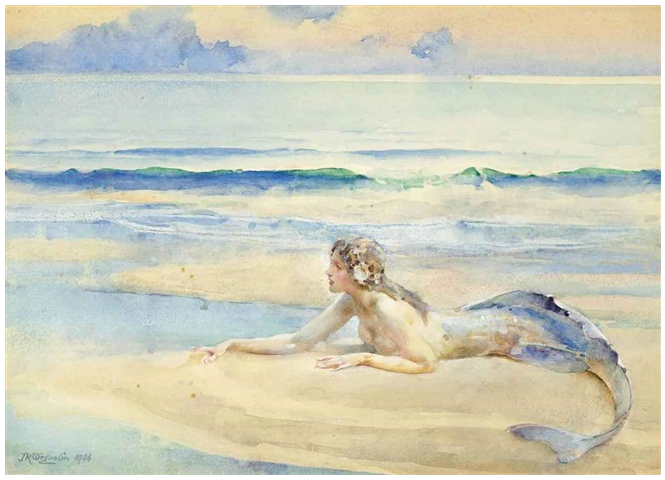

Perhaps the most complete prose account of Pablo’s legend is by Francisco Africa. His version is recorded by the American folklorist Dean S. Fansler presumably around 1911 to 1914. It can be read today in Damiana Eugenio’s Philippine Folk Literature: An Anthology (5). According to Africa, the legend was supposed to have happened in 1714 when Lipa was still beside Bombon lake. The hero, Pablo Maralit, was given the title “Don” because of his famous deeds. When Pablo was young he was asked by his parents to fish at a nearby brook. While doing so, a sirena spotted him and took him to a cave beneath Bombon lake. There he found a talisman that gave him the ability to walk on water. After escaping from the cave, he went back to Lipa by walking on the surface of the lake. Everyone was surprised when they saw him do this supernatural feat. Not long after, Pablo was caught up in a waterspout while walking by the lake. From it, he attained another talisman. Some time later, Pablo was made leader of a group of young men that was tasked to beautify their town. Their female counterparts on the other hand were led by Catalina, who Pablo was in love with. Pablo was able to win Catalina’s hand by giving her a fruit from a coconut tree that was guarded by a monstrous snake. Pablo defeated the snake with the help of his talismans. He also got another talisman from the snake. He and Catalina soon got married and Pablo was made cabeza. One day, Lipa was attacked by a fire-breathing monster. Pablo attempted to reason with the beast but to no avail. They fought from twilight to midnight and Pablo emerged victorious. From the monster he got another talisman—a magic candle. On a Holy Thursday, Pablo and his friends climbed mount Maculot to try their talismans. They saw a vine that none except Pablo could cut. When Pablo cut the vine, an old man appeared who wanted to test their talismans. He then threw Pablo down into Bombon lake. Pablo however survived due to his powers. With his sword and gun, he fought hoards of monsters in the lake for a day, until they disappeared. As a reward, the old man gave him yet another talisman which allowed him to walk on the deepest seas. Pablo then returned home, shocking everyone since they all thought he was dead–indeed they were already conducting the ritual for the ninth day of his passing.

After this, Pablo went to the land of the Igorots where he was found worthy of wearing a magic bracelet, and being a leader of their tribe. Pablo however escaped with the bracelet, and soon ended up in Manila where he witnessed hundreds of men hopelessly attempting to pull a ship stuck in the shoals. Pablo presented himself to the governor-general and volunteered to move the ship. The governor-general agreed although threatened Pablo with death if he failed. Due to his powers, Pablo was able to pull the ship like it was a toy. As a reward, Pablo became capitan or gobernadorcillo of Lipa, and his rule was a most just one. Eventually, news of his feats reached as far as Jolo. Three Joloanos then went to Lipa to challenge Don Pablo. They reached Pablo’s house and mistook him for a helper. They started chewing on the steel parts of a nearby bolo and plow, then they asked the “helper” where Pablo was. Pablo went up his house and asked Catalina to prepare the Joloanos food. He then invited them to eat. However, to their shock, their teeth couldn’t even chew through the rice that was prepared for them. Feeling humiliated, the Moros then invited Don Pablo outside so that he may see their feats. Once outside, they showed him their ability to jump over the roof of his house. After seeing this, Pablo asked them to jump over a low mortar. Strangely enough, the Moros failed to do this and so again they were put to shame. Finally, the Moros and Don Pablo went to the middle of Bombon lake to display their powers. Now Africa’s account doesn’t say what exactly happened, but the gist is that again the Moros were confounded. The story ends with the Moros humbly accepting their defeat and acknowledging Pablo’s prowess.

Remarks

I would just like to give two comments on the Pablo Maralit legend, namely, (A) its setting, and (B) Pablo’s powers.

A. The Legend’s Setting

A distinct characteristic of the legend of Pablo Maralit is that it is about someone that historically existed. Kalaw and Africa claim that Pablo Maralit served as the gobernadorcillo of Lipa in 1714 according to records (6). Now there is a list of the gobernadorcillos of Lipa from 1702-1816 that was published in an old periodical from Manila named Patnubay ng Bayan. Its digital copy is still available from the University of Michigan’s “United States and its Territories collection,” and here is the link. According to the list, there was indeed a Pablo Maralit that served during 1714 although interestingly there was also one that served in 1729. In any case, this vindicates Kalaw and Africa’s claims. If we assume that the legend happened around 1714, then the place where much of it would have occurred might be in what is now Balete, north of present day Lipa. This is because in 1702 the town of Lipa was supposedly moved there from its original location in Lumang Lipa (Old Lipa) (7). Now all this is not to say that the legend is actually real, but one is truly led to wonder what the historical Pablo Maralit did so as to gain such a fantastic mythos for himself.

B. Pablo’s Powers

In Africa’s account, we see Pablo collect a number of magical charms or talismans. Unfortunately, except for the ones that allowed him to walk on water, the power of these talismans are not described. However we can speculate what powers a couple of them have by drawing from Philippine folklore. Regarding the talisman Pablo got from the waterspout, it is possible that it is the same one that can be attained from the center of the whirlwind, since a waterspout is essentially a whirlwind on water. This talisman of the whirlwind (mutya ng ipo-ipo) in turn enhances one’s speed and can even give one control the wind. One need only do a casual google search to see that even today, the mutya ng ipo-ipo is regarded as such; indeed as of this writing there’s even one being sold online (8)! Considering this, we can make sense of what Africa says regarding Pablo’s battle with the monstrous snake. According to Africa, the talisman of the waterspout not only helped Pablo fight the creature but actually saved his life from it. What this might mean then is that the talisman of the waterspout enhanced Pablo’s speed enough for him to survive and best the snake. Speaking of the snake, Pablo also acquired a talisman from it. This in turn could have been the talisman of the boa (bato ng sawa), assuming that the snake was indeed a boa (sawa). This talisman can be found in the animal’s tail and can give its possessor the strength of ten men, as a previous post has already stated. If this is indeed the case, then it makes it easier for us to understand how Pablo could defeat the many monsters he faced afterwards. As for Pablo’s other magical items, namely, the fire-breathing monster’s candle and the Igorot bracelet, perhaps they helped him in his other exploits such as the pulling of the ship in Manila, and his dealings with the Joloanos.

Conclusion

In the beginning of this post, I said that Pablo Maralit can be likened to other Filipino epic heroes. However, Pablo cannot be an epic hero because there is strictly no epic about him. In his article “A Survey of Philippine Epics,” E. Arsenio Manuel says that two conditions that make a piece of folktale a Philippine epic is that first it must be set in verse, and second it should be chanted or sung (9). The above accounts of Pablo’s legend however are only in prose. Despite this, there is another account of Pablo’s legend that I believe comes close to fulfilling Manuel’s conditions. I’ll discuss that next time in the second part of the post.

Footnotes:

(1) Wenceslao Emilio Retana, El Indio Batangueño : (estudio etnográfico) 3rd ed. (Manila: Tipo-Litografia de Chofre y Cia, 1888), p. 42. Digitized version available in University of Michigan “United State and its Territories” collection. Url: http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ABW7511.0001.001

(2) Teodoro M. Kalaw, “Ita Missa est (Epilogo)” in Bajo los Cocoteros ed. Claro M. Recto (Manila: Libreria “Manila Filatelica”, 1911), pp. 230-231. Digitized version available in Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Url: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmcht4h4.

(3) Teodoro M. Kalaw, Cinco reglas de nuestra moral antigua: una interpretación. (Manila: Manila Bureau of Print, 1935), pp. 14-15. Digitized version available in Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Url: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmcm63d2.

(4) Leon Bibiano Meer. Legends Among the People of Batangas, in H. Otley Beyer Ethnographic Collection, National Library of the Philippines Digital Collection, pp. 2-3. Url: http://nlpdl.nlp.gov.ph/OB01/NLPOBMN0037001053/datejpg.htm.

(5) Damiana L. Eugenio. Philippine Folk Literature: An Anthology. (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2007), pp. 220-224.

(6) Retana claims that Pablo served in 1744 but this is probably a typographical error.

(7) Thomas R. Hargrove. The Mysteries of Taal: A Philippine volcano and lake, her sea life and lost towns. (Makati: Bookmark Inc., 1991), p.57

(8). https://www.carousell.ph/p/mutya-ng-hangin-o-ipoipo-239341168/

(9). See: E. Arsenio Manuel, “A Survey of Philippine Folk Epics,” Asian Folklore Studies, 22 (1963): p.3.

ALSO READ: The Legend of Pablo Maralit, (epic) Hero of Batangas: Part 2