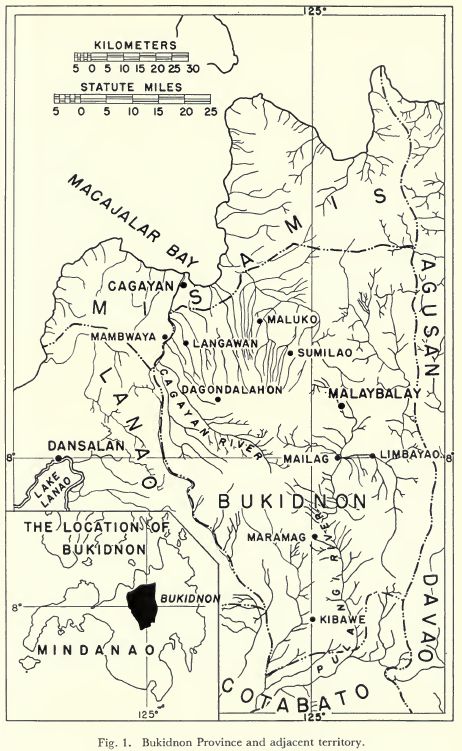

According to oral history of the indigenous people of Bukidnon, there were four main groups in Central Mindanao: the Maranaos who dwell in Lanao del Sur, and the Maguindanao, Manobo and Talaandig groups who respectively inhabit the eastern, southern, and north-central portions of the original province of Cotabato. When the civil government divided central Mindanao into provinces at the turn of the 20th century, the groups included in the province of Bukidnon are the Talaandig and the Manobo, as well as other smaller indigenous people of Mindanao. The Visayans, particularly the Cebuanos and the Hiligaynons from the Northern Mindanao coastline and the southern Visayas, migrated into the province. The Visayans are still referred to by the indigenous people of Mindanao as the dumagat (“sea people”) to distinguish them from the original mountain groups.

The contents of this article have been taken from the 1956 book The Bukidnon of Mindanao by Fay-Cooper Cole, and may not accurately represent the beliefs of the modern peoples of Bukidnon province. The bulk of the research was conducted at the beginning of the 20th century and has been amended to include later research conducted by Frank Lynch after WWII. Further, regional beliefs among the people of Bukidnon vary from region to region. Since these are living beliefs, they have continued to evolve over the last one hundred years. In some cases Catholic traditions have replaced the indigenous ceremonies that were previously performed. The Bukidnon studied in this report usually refer to themselves as Higaonan, “mountain dwellers,” but [at the time] were better known as Bukidnon, a name applied to the mountain people by the coastal Bisayan [speakers]. Many of the beliefs outlined in this report are still reflected in some modern Higaonan, Talaandig, and Mansaka beliefs. A comparative study can be made using later research presented in the book The Bukidnon Batbatonon and Pamuhay: A Socio-Literary Study, Esteban, R. C., Casanova, A. R., Esteban, I. C., UP Press, 2011.

The bulk of the following study appears to have been conducted in the village of Langawan.

Bukidnon Spirit World

Any attempt to understand or to describe the spirit world results in great confusion. The investigator learns of a spirit—its name, attributes, place of residence and other details—then suddenly it may appear to be several spirits. The account which follows is, I believe, an accurate picture of what the average Bukidnon believes and understands. The special knowledge of the baylans is noted in each instance where it exceeds or contradicts the usual pattern of belief.

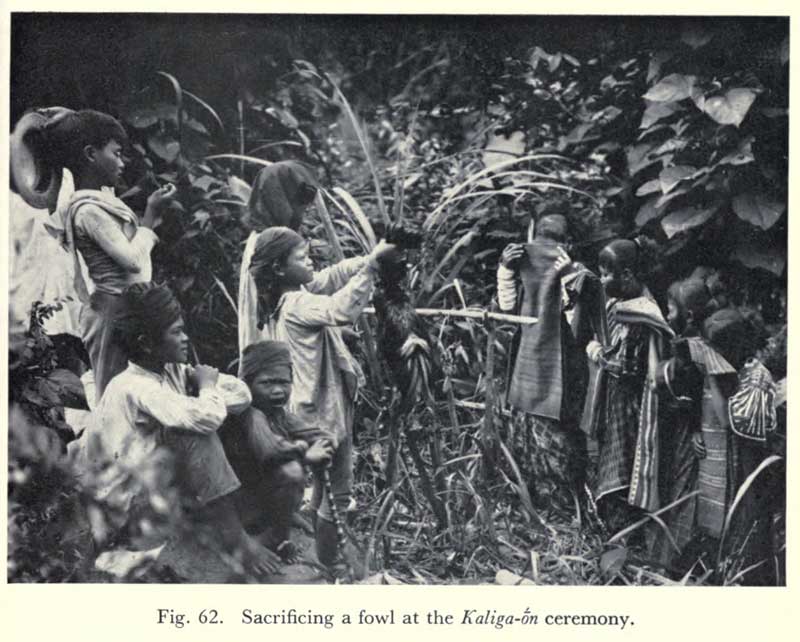

The Bukidnon recognizes three classes of spirits. First to be noted are the gimokod—the spirits of all men living or dead. Second are the Alabydnon—a division which includes most of the powerful spirits. Finally come the Kaliga-ṑn, sixteen powerful beings which are represented at certain ceremonies by well-known symbols. They keep watch over the affairs of men and warn offenders by sending illness. The harvest ceremony is held in their honor, although other spirits appear at that time. In addition to these three classes, the baylans sometimes mention a fourth, made up of unfriendly spirits called busau or bal-bal. Actually it seems that they should be included under the Inkanto, the second group of Alabydnon.

Bukidnon Baylans

Most traffic with the spirit world is through or with the aid of the baylans —a group of men or women who claim the ability to discover the cause of sickness. They also know how to conduct ceremonies acceptable to the spirits. It is said that the first baylan was taught by Molin-olin, the spirit of his afterbirth brother (see p. 69), who for this reason is considered a patron and guide. Two other spirits, Ongli and Domalondon, also appear to the baylan and usually assist in determining the cause of the trouble. The baylans do not form a priesthood, although they are a definite group. Should one of them be visiting in a village where a ceremony is in progress he or she assists as a matter of course.

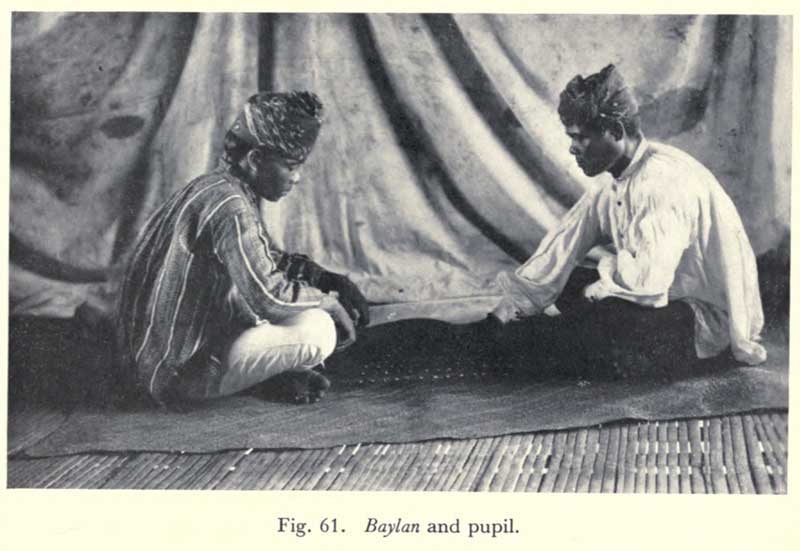

A person becomes a baylan as a matter of choice, and not because he is called or warned by the spirit world. He goes to a recognized baylan and acts as his understudy for several months, during which time he receives other special training. The writer watched a teacher and pupil over a considerable period of time. The baylan would spread a mat and on it place kernels of corn in a row. These represented spirits whose names and attributes were repeated many times until the pupil had memorized them perfectly. Next the instructor described the ceremonies and the things to be done in each. Then followed the songs, many of which contain obsolete words.

It is said that some baylans possess special gifts or powers, such as the ability to go to the sky and talk with the spirits there, but in general the content of their training and their competence is similar. The field notes which contain data from a number of baylans in various parts of the Bukidnon area show a surprising agreement in names and duties for a bewildering number of spirits. Likewise the ceremonies vary but little from town to town. A pupil pays for his instruction. For example, the ranking baylan of the village of Langawan claims to have paid his teacher nine pesos, eight chickens, one Chinese plate and a small knife.

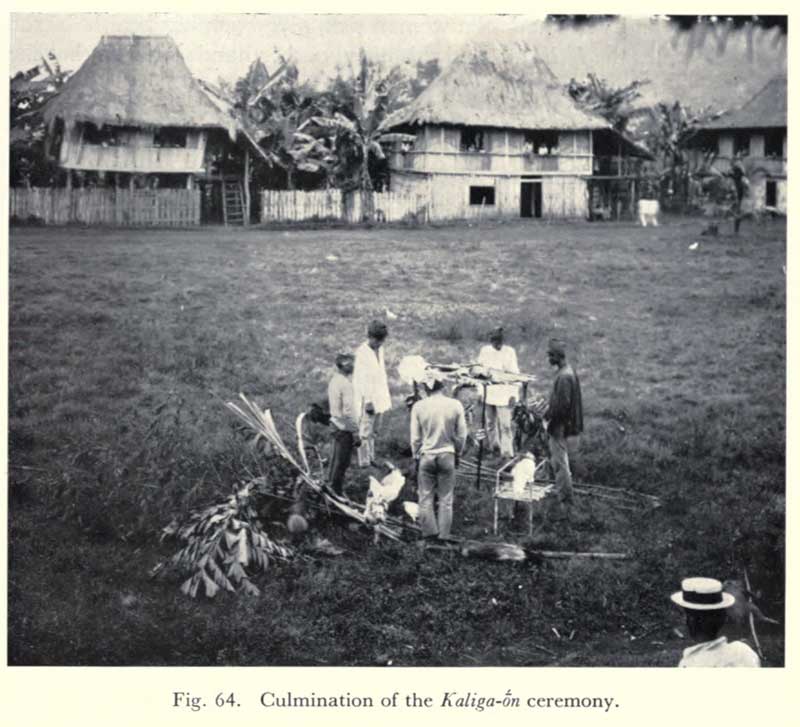

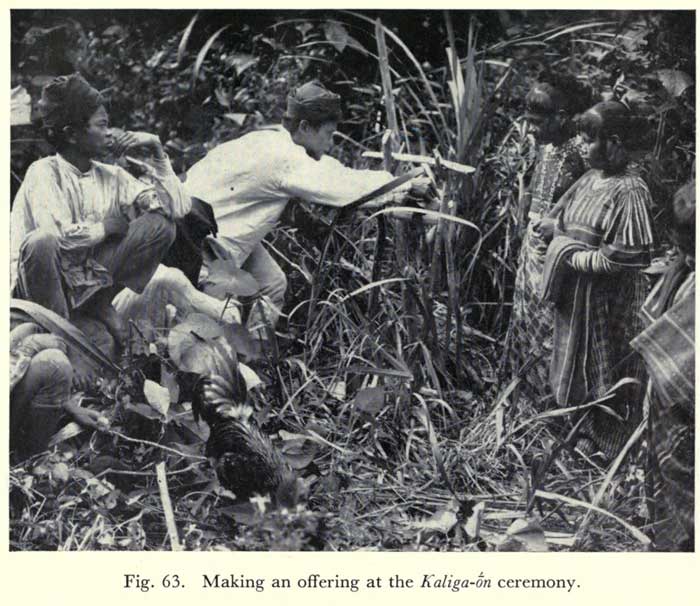

The baylans must conduct the Kaliga-ṑn ceremony and they usually officiate at all major events where the spirits are summoned. (However, minor offerings may be made by anyone “who knows how to talk to the spirits.”) Payment for their services is small and varies, according to the spirits summoned, from a few pennies to a peso. In addition they receive six packages of cooked rice, half of a pledged chicken (ipo), and all the rings and beads used in the ceremony.

The customary way of ascertaining the cause of trouble or the name of the spirit responsible for illness is for the baylan to measure a spear. He holds the weapon horizontally in front of him and measures the span of his arms on it. This is marked by tying a cord on the shaft which is then stuck into the floor. Betel nut is prepared for chewing and is placed on the floor. The baylan seats himself before it and addresses the proper spirit. (This differs according to the ceremony.) The substance of the prayer is an appeal for the speedy recovery of the patient, and for power to determine the cause of the illness. Finally he pleads, “If the sickness is caused by so-and-so I ask you to let the measurement on the spear be extended.” He rises and again measures the span of his arms. If it is the same as before, the spirit named is not responsible, but if it has increased it is a sign that the right spirit has been found. In any case the measuring is continued until the cause is determined.

The various activities of the baylan appear in connection with the discussion of the spirit world and description of the ceremonies. It is important to note that the baylans are not “mediums” in the sense that is usual among Malayan peoples. They carry out many of the duties of the mediums, but their bodies are not possessed by the superior beings. They do not appear to be unstable characters as is so common among the mediums of the nearby Manobo or of Malaysia in general.

The number of baylans in the towns varies greatly. In the village of Langawan there are six, namely: Mangontawal, Amaydolona, Amaylania, Amaydayano, Salilo and Sampayan.

Spirits of the Bukidnon: Gimokod (seven spirits of the individual)

In our discussion of spirits we deal first with the individual Bukidnon. Each person has seven spirits called gimokod: one jumps on the cliff; one swims in the water; one puts its hands into snake holes; one sits under a tree; one is always walking around; one is awake in the day; one is awake in the night. If all are in his (or her) body at the same time, he is well and strong, but if one or more are wandering or get into trouble, the owner becomes ill. Should all the gimokod leave the body at one time death results.

This idea of multiple spirits leads to several unusual practices, among which “soul catching” is of special importance. When a person becomes thin or ailing with no apparent reason, it is evident that at least one of his gimokod is wandering. It then becomes necessary to hold the Pagalono (Pag-gimokod) ceremony, to cause its speedy return—otherwise it may meet with disaster, and its owner will fall sick or die, or at least become disabled.

A small chicken is killed and prepared for food, but its legs and feet are removed, for those might encourage the gimokod to wander. It is then placed on a dish of cooked rice. A mat is spread near the patient and on it are placed the food, prepared betel nut and a betel nut box. The baylan addresses the spirits: “Now I call you, gimokod of this man which is walking about; and you gimokod which sits under a large tree; and you gimokod which jumps on the cliff; and you gimokod which swims in the water; come here and eat, you are hungry. Return now to the body of this man. Now enter the betel box.” Suddenly he snaps the lid of the box, as he cries, “This is the sign that I will not let you go, for I fear you may be frightened by falling trees or rolling stones.” The people eat the food and chew the betel nut, but the spirit is left imprisoned until next morning. At that time the baylan places the betel box on the patient’s head and says, ”Gimokod of this man, I want you to return so that he may become well again. Do not walk any more. Let him become fat.”

When a man dies his seven gimokod merge into one which, after the Mag-kataposen ceremony, goes to live on Mount Balatocan. “We know that this is what happens, for our ancestors have taught us to call only one gimokod of the dead, so that must be all there are.” In this new home the gimokod are under the care of the spirit Gomogonal. There they have houses, plant crops, and live much as they did on earth. The home of the gimokod is said to be a happy place where there is no trouble, and people have clear minds. Despite this promise of a happy hereafter, every effort is made to delay entrance to the land of the dead. The dead do not die again, neither do they return to earth in any other form. However, they do visit the living although they may not be seen. They have power to injure the living so it is always a good idea to offer them food and to pray to them at the time of ceremonies. In some instances they cause illness. When this occurs the victim can see the gimokod.

Such offerings raise the question of ancestor worship. Regard is paid to the gimokod of the dead, as just noted. The ancestors are also called upon at the time of a wedding, but such attentions are on a minor scale. In only one area—close to the Manobo—is a major ceremony held in their honor.

Related to the person, but not one of his gimokod, is the Molin-olin, the spirit of the afterbirth. It is said by some that if a person has been very bad while on earth the spirit Gomogonal may put him in a burning hill, called Dildilosan, where he is consumed. It may be suspected that this idea has come about through contact with the Bisayan.

The Alabyanon: Magbabaya and Natural Spirits

The second and in many respects the most important class of spirits is known as Alabydnon. This is at once subdivided into the Magbabaya and “natural spirits,” the latter including the spirits which live in trees, cliffs, water and the like. Here also appear the spirit owners of animals and certain guardians or patrons. These are again divided so that those of the immediate locality have individual names.

Ranking above all others are six powerful Magbabaya, while a few other Alabydnon are ranked as lesser members of that group. So powerful are these beings and so great is the awe of them that even the baylans fear to mention their names without making an offering, and even then the name is given only in a whisper. In general they are addressed in honorific terms, which makes their identity even more difficult for the investigator to discover.

Standing high above all others is “Magbabaya nang-gomo tilokan nanilampu” (Magbabaya most powerful of all; destroyer of all competitors.) He usually is identified as Migloginsal or Agobinsal, the creator of the earth. He is also addressed as “Lintowangan nanlimlag diwata nangaroyan balos sa nanggantian,” (the spirit who made trees, stones and people) or simply as Diwata Magbabaya or Apo (Sir). This all-powerful spirit lives in a house made of coins, high in the sky. There are no windows in his home, for should men or stones or trees see him they would at once dissolve into water. His name is never used in conversation and is only taught to the new baylan after a long period of probation. When questioned about this spirit one old woman baylan became very ill. She showed great distress, vomited and appeared near collapse. Only the application of “powerful medicine” by the writer brought her out of the spell, but she could not be induced to continue the discussion. The ranking baylan of Langawan, named Amaydolona, was finally persuaded that all the facts about this spirit should be recorded. In evident fear he addressed the spirit, asking his pardon. He then gave his name in a voice only a little above a whisper. Soon he also developed stomach pains and had to be treated. This attempt to learn the details about the spirits was not made until we had been with the Bukidnon some time and had obtained their confidence. It is probable that an early inquiry would have stopped the work completely.

The second Magbabaya, only slightly inferior to the first, is known as Magbabaya tominapay or Diwata na-napay tomas a nipirau, “the spirit who lives

under the earth and supports it with his hands.”

Next in power are the Magbabaya at the four cardinal points. The earth is shaped like a saucer, and the sky is the same in form, but its concavity is toward the earth. These Magbabaya live at the points where earth and sky meet.

The spirit in the east is Magbabaya imbaiu, “spirit of the sun.” He is not the sun, but there is a hazy idea that the sun is a male spirit who serves the Magbabaya.

The spirit in the west is Magbabaya Lindon-an, “spirit of the place where the sun hides.”

In the south is Magbabaya Pagosan, “spirit of the place whence the waters come.” Nearly all the rivers in this section flow from the south—”so the water lives in the south and goes to the north.”

Finally comes the spirit of the north—Magbabaya Tiponan—”spirit of the place where the waters unite,” i.e., the ocean.

Father Jose Maria Clotet (1889) gives the four gods at the cardinal points as Domalongdog, Ongli, Tagalambong and Magbabaya. The first two, according to our information, are the patrons of the baylans. He calls Magbabaya “The All Powerful One.”

In Langawan the baylans also recognize as very powerful Magbabaya minumsob togdwa nangalangan, “the spirit who protects people and who foresees events.” He lives straight above in “the sky easily visible.” He is the grandfather of Malibotan, the spirit of the Kasaboahan ceremony. It is said that the Magbabaya live in houses like those of the Bukidnon except that they are made of silver.

A second group of Alabyanon is known as Pamahandi. In general the Pamahandi are spoken of and are addressed as a single individual. He is said to be the spirit who cares for horses and carabao and who sends good fortune. In such a capacity he is often recognized as one of the lesser Magbabaya. Closer acquaintance with this being reveals that he is not one but ten—each with a definite name and specific duties. Their names are Pamahandi putt, Pamahandi lansion, Pamahandi biohon, Pamahandi sigolon, Pamahandi hagsalan, Pamahandi bonau, Pamahandi opos, Pamahandi logdangon, Pamahandi komagasgas, Pamahandi somagda. Not all of these names are recognized in the Central Valley, but there is agreement as to the number and duties. As protectors of the horses and carabao and as senders of good fortune, they are much respected and some time during each year each family will make a ceremony to obtain their good will. Despite their good qualities, however, they may cause trouble and send sickness, such as earache or consumption.

Another multiple spirit, often ranked as a lesser Magbabaya, is Bulalakau, the spirit or spirits of the water. They have their home in the center of the sea but they also frequent springs, streams and rivers. They are sometimes spoken of collectively as Talawahig, “dwellers in the water.” One of these spirits is responsible for drowning. He pulls a person down, takes out his spirit, and throws the body to the surface. “We know that this is true for when the body is recovered the spirit is gone.” Bulalakau properly belongs to the group of nature spirits known as Inkanto, and he is often addressed with others in that division.

Particular spirits, classified as Alabydnon but not easily fitted into regular groups, are:

First, Molin-olin, the spirit of the afterbirth. When a child is born a spirit “brother” is likewise born. When its body is buried and becomes earth the spirit goes to the sky, where it lives and watches over its living brother. It never dies. “We do not know how it lives, but its home is straight above and it swings, maybe in a cradle—for the prayer taught us by our ancestors and used by the datos when they act as judges starts with ‘Now my Molin-olin who is swinging high up in the sky.'”

Spirits two and three, Domalon-don and Ongli, are patron spirits of the baylans and of datos who act as judges. They should be asked to give “a clear mind.”

Four and five are Panglang and her servant Mangonoyamo. These are female spirits who care for midwives, pregnant women, and unborn children.

Number six is Palilitan, a young male spirit for whom the miniature cradle is hung over a new-born child. It is his duty to protect the infant from sickness and danger. He is a servant of Panglang, but is not recognized by the baylans of the Central Valley.

Number seven, Gomogonal, is the spirit of a man who lived in the “first times.” He now has his home on Mount Balatocan where he looks after the spirits (gimokod) of the dead. He is regarded as a true member of the Alabydnon.

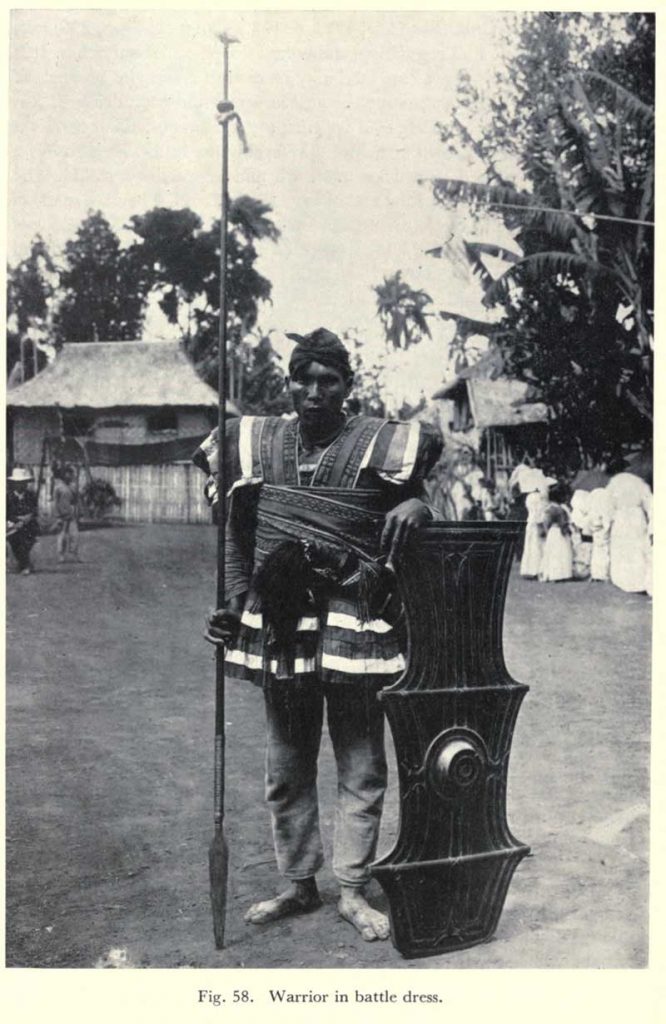

Number eight, Talabosau, is the patron of the warriors and of people who run amuck.

Nine, ten and eleven consist of Omalagad, patron of the hunters and their dogs. (In the Panalikot ceremony he is recognized as chief of the spirits of the rocks, cliff’s and trees. It is said that he is as powerful as Bulalakau.) With him is his aid, Magomanay, who lives in the high mountains. He is the real owner of the deer and wild hogs. (Here we find a conflict among the baylans, some of whom insist that the latter spirit belongs to the Inkanto division, and that he is one of two spirits which live in the baliti trees.) The third spirit associated with Omalagad is Dumarahol. The name SalikEt is often applied to all three.

Number twelve is Amimisol, who cares for the chickens. Should the fowls of a village be ailing a hen is made ipo, that is, pledged, to this spirit. If this fails to make things right some of the eggs or one of the chickens of the ipo bird are destroyed. In the Central Valley this spirit is thought to care for domestic pigs as well as fowls.

Thirteen, an important spirit in the Cagayan Valley but not recognized in the Central area, is Malibotan. He is said to be the grandchild of Magbabaya minumsob. Together with his grandfather he oversees married couples. For them each family holds a yearly ceremony known as Kasaboahan, “union.”

Number fourteen, the final spirit in this category, is Aguio. Once a man famed for his bravery as a warrior, he is now a spirit who lives on earth and sometimes attends the Kaliga-ṑn ceremony. He also appears in the folk tales.

A group of seven Alabyanon appear as servants to the Kaliga-ṑn. Their names are given to clarify their place when and if they are called during the ceremony. These are Holldon or Holoyodon; DEgbason; Pamogya-on; Lumolumbak kobaybay, dato malabidaya, “the pilot when the Kaliga-ṑn make trips”; Mayaki lioban; Mayaki batasan or kompasan; and Mayaki lombdran.

The “nature spirits” are lesser Alabydnon. Among them Bulalakau is listed although he is usually considered as a lesser Magbabaya. General names such as Tagabogta, “lives in or on the earth,” or Tagumbanua, for those living near a town, are often applied. It is said that their chief lives on a mountain called Babonan but the others live everywhere. Among them is Tao sa salup, “man of the forest.” A more specific name for these nature spirits is Inkanto but the term busau is also used. It is said that the Inkanto have only half a face; the body is complete but many of them walk on their hands with their heads hanging down and their feet up. Some have fur on their bodies but the hairs are sharp like needles.

Clotet (1889) mentions a spirit Ibabasug who is invoked in childbirth. According to him Tagumbanua is god of the fields to whom the Kaliga ceremony is dedicated.

Finally we come to the local spirits. Every cliff”, strange stone, spring and brook has its resident spirit. Each has its name which is known to the villagers. A partial list was compiled for each village, but these appear to have no significance beyond demonstrating the multiplicity of locally known spirit beings.

The Kaliga-ṑn, Spirits of the Hills & Mountains

The third and last class of spirits is the Kaliga-ṑn, made up of sixteen powerful spirits who dwell in high hills or mountains, particularly in volcanoes.

The sixteen are:

(1) Dagingon

(2) Korongon

(3) Liga-on

(4) Bontialon,

(5) SEgkaron

(6) Laulau-on

(7) SapawEn

(8) Linankdban

(9) Masaubasua

(10) Tagalambon

(11) Hinoldban

(12) Sayobanban

(13) Moyon-boyon,

(14) Gologondo

(15) Lantangon

(16) Tambolon

All are powerful but Gologondo and Tagalambon appear to lead the others, with Lantangan and Hinoloban following.

Certain objects which belong to, or represent, these beings must always be used in the ceremonies they attend.

Two or three sticks tied horizontally and called dagingon belong to the first six named. Four sticks tied in the same manner are also called by this term, but this number is reserved for SapawEn.

Basket-like receptacles made of tiny bamboo tubes are filled with leaves and contain part of a pig’s skull. These are known as golon-golon and are for spirits nine to fourteen inclusive.

Lantangan is represented by a small carved figure, while a single bamboo tube is reserved for Tambolon.

A “table” made of wooden disks slipped on a salaban stick is prepared for the four strongest spirits. The detailed use of these devices is given in connection with the Kaliga-ṑn ceremony. The term diwata is often applied to the Magbabaya and Kaliga-ṑn, but never to the lesser Alabyanon, or to the spirits of the dead. A title, tomitima, “lives,” which may be applied to any spirit is frequently heard in the ceremonies.

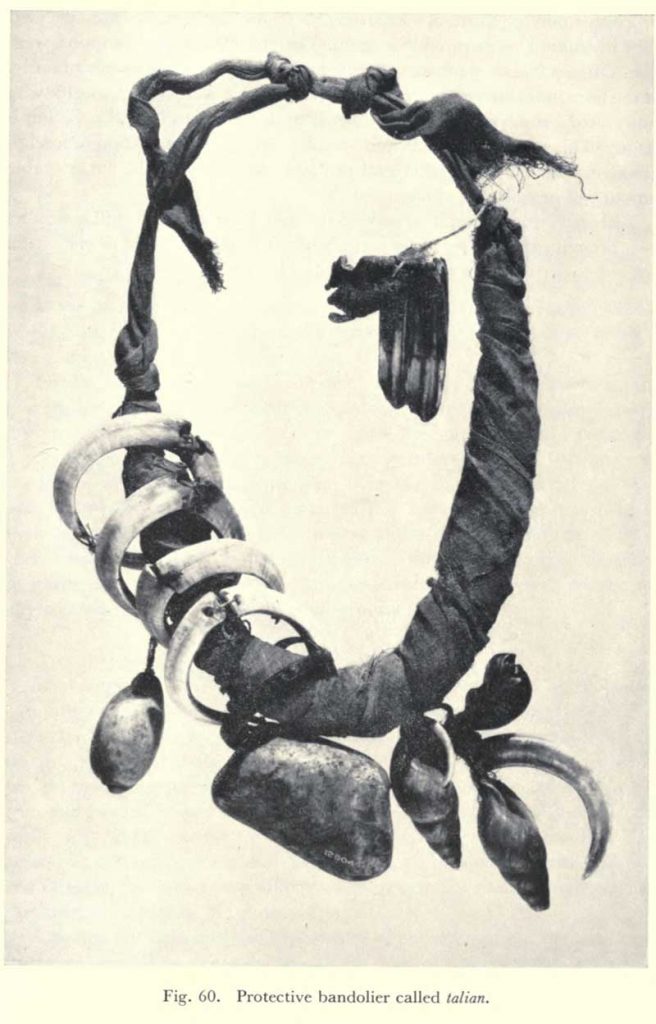

Clotet (1889) describes a stone idol called tigbas which he says descended from the sky and is possessed only by datos. Today a few peculiar stones, called tigbas a kilat, “teeth of the lightning,” are in the possession of the Bukidnon. These stones are said to have fallen where lightning has struck. They are powerful in stopping violent storms, for if one is laid outside, the rain will cease. No other objects by this name could be found. Clotet also describes wooden figures of monkeys called talian. That name is now given to the charmed bandolier worn by noted warriors, which may contain various objects.

Fowls and animals belonging to the spirits are sometimes referred to in the ceremonies, and occasionally offerings consisting of refuse are put out for them, but they are not considered to be spirits. On several occasions the writer was told that the earth rests on two huge serpents, male and female, called Intombangol, who lie so as to form a cross. Their mouths are below the water at the point where earth and sky meet. When they move they cause earthquakes; when they breathe they cause the winds; if they pant they cause violent storms. They do not fall for they are held up by Magbabaya tominapay. There seems to be no general agreement about these beings, but some baylans think they should be classed as lesser Alabyanon.

Spirits of the Balete Tree

Earlier, mention was made of the spirits of the baliti (Ficus sp.) trees. These trees are held in reverence by nearly all Mindanao tribes, partially because of their size and partially because they “bleed” when cut, and also because nothing grows beneath them. If a piece of land is to be cleared and it becomes necessary to cut down one of these trees, the owner of the field will go alone and cut a sapling. He strips off the bark and leaves and leans the pole against the haliti tree. Then he addresses the spirits as follows: “If there is a man living in this tree, here is wood for you to use as a sign. If you are unwilling that I cut this tree, throw this wood away. If it pleases you to have this tree cut down, then leave this pole where it is.” He then goes home. Next day he returns and if the stick has fallen or has disappeared it signifies that the spirit is unwilling. If the stick is still in place, the spirit gives consent. Then the owner says, “Now I am going to cut the baliti tree right away. If the owner is still here, please go to that other tree.” Often he prepares betel nut for the spirit and places it at the foot of the tree as he says, “You man of this tree, go away, for we are going to cut it down so that we can clear our field. You must not be angry with us when we destroy your house for here is your payment. Come and chew and do not be angry.”

Closely related to the acts just cited is a minor ceremony called Magibabaso. At the time a clearing is to be made in the forest the owner goes to the chosen spot accompanied by several friends. They carry rice, chicken eggs, betel nut and liquor. A seat is constructed and the chickens are tied beneath it. Betel nut prepared for chewing is placed on it and the owner of the field addresses the spirits of the stones, baliti trees, vines, cliffs, and of any holes that may be in the field. He also calls on Maghabaya and Ibabaso: “Now do not be angry with me because we are about to clear this land; do not be surprised or offended for we are going to kill some chickens and let you eat rice, drink agkEd, and eat meat. When we go to plant, let the seed bear a good crop.” All the people present blow upon the chickens and then kill them.

While the food is being prepared some of the people begin the clearing of the land while others build a balabag. When all is ready food is placed on the seat and the workers are summoned. Again the owner summons the spirits. He invites them to eat, and having done so, to be satisfied and not injure those who would use the land.

SOURCE: The Bukidnon of Mindanao, Cole, Fay-Cooper, Martin, Paul S., Ross, Lillian A., Chicago Natural History Museum Press, (1956)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.