|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

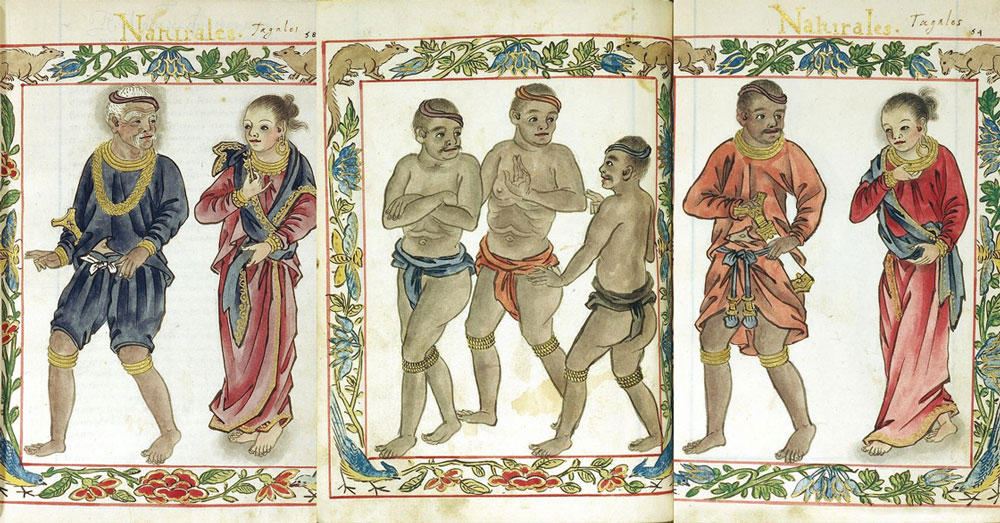

The Tagalog people are one of the largest ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, numbering around 30 million. They are native to the Metro Manila and Calabarzon regions of southern Luzon, and comprise the majority in the provinces of Bulacan, Bataan, Nueva Ecija and Aurora in Central Luzon and in the islands of Marinduque and Mindoro in Mimaropa.

Just as we are often reminded that there is no “Philippine Mythology”, but rather a collection of mythologies and religions from the various ethnolinguistic groups, we must also remember that not all regions within an ethnolinguistic group share the same beliefs. For instance, according to F. Landa Jocano (Outline of Philippine Mythology), the Manobo supreme deity is Tagbusan. John Garvan documented the Manobos of Agusan holding Magbabáya as their supreme being. Different still, the Manobo people of Mt. Apo believe in Monama, the Creator. Not only do they differ in name, but their activities and temperaments also seem to vary.

Making things more confusing, we can really only review the documentation as a guideline to the beliefs as they existed at the time of documentation. I can’t even begin to recall the multitudes of times I have seen nonsensical squabbling on social media over different myths because these concepts are not always easy to grasp:

– Different ethnolinguistic groups have different beliefs.

– Different regions and communities within an ethnolinguistic group may have differing beliefs.

– Documentation is a snapshot in time. Written material may not represent the evolution of a groups beliefs.

– Sometimes documentation is wrong, no matter how prestigious the chronicler or institution.

A perfect example of the above disagreements would be the well known Tagalog deity Amanikable or Amanikoable – an idol of the hunters. This stems from an entry by Buenaventura in 1613: idolo: Amanicable: abogado de los caçadores, llamanle quando yvan acacar. In contemporary Tagalog mythology Amanikable is the husky, ill-tempered ruler of the sea. The ‘newer’ description was collected by F. Landa Jocano in two different myths. For a reconstructionist of Tagalog religion, one may prefer to use the earliest account. That approach, however, does not take into account that different Tagalog regions very likely had different deities and anitos that they worshipped. In the case of Amanikable, perhaps he was a protector of hunters gathering food inland, and in the seaside area of Cavite (where Jocano’s myths were recorded), he was the protector of fisherfolk gathering food.

The popular pantheon of Tagalog deities has been reinforced for two simple reasons: The documentation was made in population centers, and the Spanish were great plagiarizers of each others work. It is extremely likely that the entirety of nuances among regional deities and anitos among the early Tagalogs has been lost. Thanks to Felipe Pardo, we have been given a snapshot of deities in Santo-Tomas, Laguna from 1688.

This work is of particular interest because it gives clues to the transition of influence in the Laguna region from the Indosphere of greater India, where numerous Indianized principalities and empires flourished for several centuries in what are now Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Cambodia and Vietnam into a syncretization with Islam that was noted in Manila when the Spanish arrived.

Below are the deities that were recorded. I have included the notes of Jean-Paul G. Potet from his entry in the book Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. I only have one personal note to add regarding Anatála. I have seen it mentioned several times in various blog posts and Wikipedia entries that Anatála is another name for Bathala (Tagalog supreme being). I’m not sure there is any evidence to prove this is accurate. Bathala was derived from the Sanskrit word bhattara or bhattaraka. Areas documented with beliefs in Bathala were, at that time, under a cultural influence from the Indosphere of greater India. The term Bathala was also used in the Tagalog and Cebuano areas to refer to the Christian God after the arrival of the Spanish. Anatála could represent a transition to a more Islamized syncretic cultural influence. The term Alatala comes from the Arabic Allah Ta’ala, meaning “God the Great One” (Adriani and Kruyt 1950, 2:chap.12; Weinstock 1987, 78). Some Sulawesi people also refer to “god” as Alatala. Use of the term in Laguna ‘could’ have replaced the name Bathala, but like the Manobo people of Mindanao, this Tagalog region could also have had a different name for their creator. We will never know what name was replaced by Anatála and I don’t feel there is enough similarities in the Santo-Tomas and more popular Tagalog pantheon to assume it was Bathala. All we know for certain is that in 1688, the word for “creator” or “god” in Santo-Tomas, Laguna was Anatála.

I believe that the Santo-Tomas list of deities represents a system of beliefs based on Animism, influenced heavily by the Indosphere of greater India. The Laguna Copperplate is perhaps the best relic to establish this influence. The plate was found in 1989 by a labourer near the mouth of the Lumbang River in Wawa, Lumban, Laguna in the Philippines. The inscription was mainly written in Old Malay using the Early Kawi script with a number of technical Sanskrit words and Old Javanese or Old Tagalog honorifics. By the 15th century, half of Luzon (Northern Philippines) and the islands of Mindanao in the south had become subject to the various Muslim sultanates of Borneo and much of the population was adopting Islamic beliefs. In 1577, Spanish Franciscan missionaries arrived in Manila, and in 1578 they started evangelizing Laguna, Morong (now Rizal), Tayabas (now Quezon) and the Bicol Peninsula as part of the colonizing effort. The syncretization with Islam was likely halted in Laguna at that time.

NAMES OF DEITIES IN SANTO TOMAS LAGUNA

Several deities are mentioned in the paper of Archbishop of Manila, Felipe Pardo (1688) about idolatries in the town Santo-Thomas, Laguna. Although the names of many had already been forgotten by the witnesses, the number of those still remembered is nevertheless impressive. Most are absent from the other sources at our disposal.

► = comes from

Span. = Spanish spelling

Anatála = the Supreme God Mal. Alataala “God” [“alla:h tafa:la:]

“God, be He exalted.”

Alagaka ► Span. Alagaca = protector of hunters

Balakbák at Balantáy Span. Balacbac y Balantay= the two guardians of Tanguban, the abode of the souls of the dead.

Bingsól ► Span. Bingsol = the god of ploughmen

Biso [Bisô “Holeless-Eared”] Span. Biso = the police officer of heaven

Búlak Pandán ►Span. Bulac-pandan =”cotton (flower?) of pandanus”

Búlak Tálà ► Span. Bulactala= the deity of the Morning Star / the planet Venus seen at dawn (N&S 1860:3 16) (p. 128) Sans. tārá aR = a fixed star (MW 443).

Dalágañg nása Buwán = the Maiden in the Moon

Dalága ►Ginúong Dalága ► Span. Guinoo Dalaga = “Lady Maiden”, the goddess of crops.

Dalágañg Binúbúkot = the Cloistered Maiden (in the Moon)

Gánay ► Ginúoñg Gánay Span. Guinoong Ganay = “Lady Old Maid”

Hasanggán ►Span. Hasangan = a terrible god

Kampungán ► Maginúoñg Kampungán ► Campongan = Lord Supporter”: a god of harvests and sown fields.

Kapiso Pabalítà ► Span. Capiso pabalita = “News-giving”, protector of travelers.

Lakapátì ► Span. Lacapati = the god of vagrants and waifs.

Lampinsákà “cripple” ► Span. Lampinsaca= the god of the lame and the cripple.

Makapúlaw ► Span. Macapulao = “Watcher” the god of sailors.

Makatalubháy ► Span. Macatalubhay = the god of bananas.

Matandâ ► Siyák Matandâ ► Span. Siac Matanda = “Old Sheikh”: the god of merchants and second-hand dealers.

Ang Maygawâ ► Span. Ang Maygawa = The Owner of the Work.

Paalúlong ► Span. Paalolong = “Barker”, the god of the sick and the dead.

Paglingniyalán [?]► Span. Paglingñalan = the god of hunters.

Pagsuután ► Ginúoñg Pagsuután ► Span. Guinoong pagsohotan = Clothing Lady”, protectress of women in travail.

Pagwaagán ► Span. Pagvaagan = the god of winds.

Panáy ► Ginúoñg Panáy “Lord/Lady Panay” = deity residing in a kalumpáng tree (Sterculia tree Span. La Campinay = foetida), although panay is either (Syzygium) or tuffy (cooked honey).

Pinay ► Lákañg Pinay ► Span. La Campinay “Her Lordship the old midwife Pinay”

Púsod-Lúpà ► Span. Posor Lupa = “Earth Navel”, a god of the fields.

Sirit ► Span. Cirit / Zirit [Sírit “Snake’s Hiss”) =a servant of the gods.

Sungmásandál ► Maginúoñg Sungmásandál [Sumásandál The one that keeps close”] ► Span. Maguinoong Sungmasandal.

ORIGINAL SOURCE: PARDO, Felipe, archbishop of Manila (1686-1688). Carta [..] sobre la idolatría de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomás y otros circunvecinos […] Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias, ES.41091.AGI23.6.795//FILPINAS,75,N.23.

COPIED FROM: POTET, Jean-Paul G., Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs, Lulu Press (2017) pgs. 166-167

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.