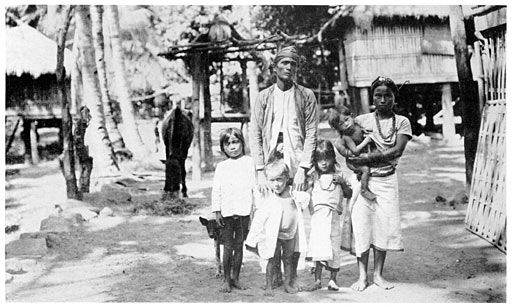

The Tingguians “the people of the mountains” originally referred to all mountain dwelling people. Nowadays, it particularly refers to a cultural minority group living in the mountains of Abra and named Itneg.

The Tingguian culture dates back to pre-Spanish times but in spite of strong external forces negatively affecting their customs, they continue to practice their ethnic traditions.

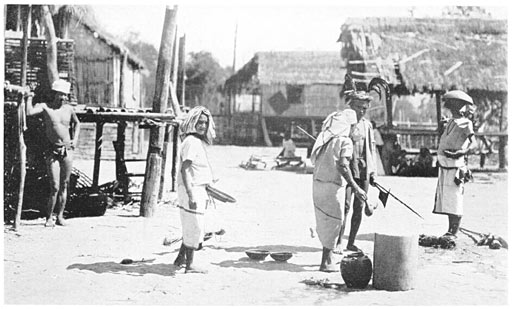

The contents of this article have been taken from the 1922 paper The Tingguian Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe by Fay-Cooper Cole, and may not accurately represent the beliefs of the modern Tingguian. Further, regional beliefs among the Tingguian vary from village to village. Since these are living beliefs, they have continued to evolve over the last one hundred years. This report states the Tingguian inhabit chiefly the mountain province of Abra in northwestern Luzon. From this center their settlements radiate in all directions. To the north and west, they extend into Ilocos Sur and Norte as far as Kabittaoran. Manabo, on the south, is their last settlement; but Barit, Amtuagan, Gayaman, and Luluno are Tingguian mixed with Igorot from Agawa and Sagada.

___________________________

An Introduction to Customs and Religion of the Tingguian:

The Tingguian has been taught by his elders that he is surrounded by a great body of spirits, some good, some malevolent. The folk-tales handed down from ancient times add their authority to the teachings of older generations, while the individual himself has seen the bodies of the alopogan (shaman) possessed by the superior beings; he has communicated with them direct, has seen them cure the sick and predict coming events. At many a funeral, he has seen the alopogan squat before the corpse, chanting a song, and then suddenly become possessed by the spirit of the deceased; and, finally, he or some of his friends or townspeople are confident that they have seen and talked to ghosts of the recently departed.

Some of these spirits are always near; and a part of them, at least, take more than an ordinary interest in human affairs. Thanks to the teachings of the elders, the Tingguian knows how to propitiate them; and, if necessary, he may even compel friendly action on the part of many. To the more powerful he shows the utmost respect; he offers them gifts of food, drink, and material objects; and conducts ceremonies in the manner demanded by them.

Custom and religion have become so closely interwoven in this society that it is well-nigh impossible to separate them. The building of a house, the planting, harvesting and care of the rice, the procedure at a birth, wedding, or funeral, in short, all the events of the social and economic life, are so governed by custom and religious beliefs, that it is safe to say that nearly every act in the life of the Tingguian is directed or affected by these forces.

Two classes of spirits are recognized; first, those who have existed through all time, whom we shall call natural spirits; second, the spirits of deceased mortals. The latter reside forever in Maglawa, a place midway between earth and sky; but a small number of them have joined the company of the natural spirits. Except for these few, they are not worshiped, and no offerings are made to them, after the period of mourning is past.

The members of the first class cover a wide range, from Kadaklan, the great spirit who resides above, to Kabonīyan, the teacher and helper, to those resident in the guardian stones, to the half human, half bird-like alan, to the low, mean spirits who delight to annoy mortals. These beings are usually invisible, but at times of ceremonies they enter the bodies of the alopogan, possess them, and thus communicate with the people. On rare occasions they are visible in their own forms, as when Kabonīyan appeared as the antagonist and later as the friend of Sayen.

These beings are addressed, first through certain semi-magical formulas, know as dīams. These are seldom prayers or supplications, but are a part of a definite ritual, the whole of which is expected to gain definite favors.

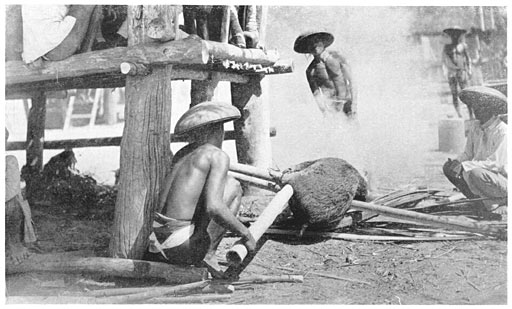

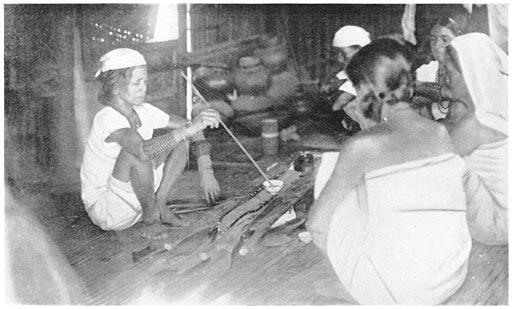

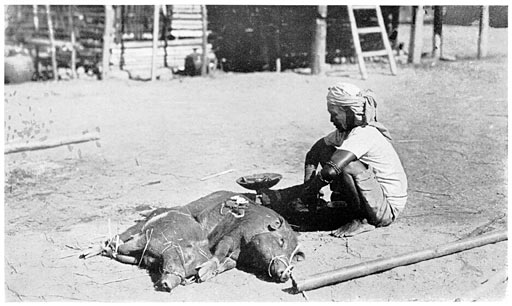

At the beginning, and during the course of all ceremonies, animals are killed. A part of the flesh and the blood is mixed with rice, and is offered to the spirits; but the bulk of the offering is eaten by the participants. Liquor is consumed in great quantities at such a time, but a small amount is always poured out for the use of the superior beings. Finally, the alopogan summon the spirits into their bodies; and, when possessed, they are no longer considered as persons, but are the spirits themselves. The beings who appear in this way talk directly with the people; they offer advice, give information concerning affairs in the spirit world, and oftentimes they mingle with the people on equal terms, joining in their dances and taking a lively interest in their daily affairs.

The people seldom pray to or supplicate the invisible spirits; but when they are present in the bodies of the alopogan , they make requests, and ask advice, as they would from any friend or acquaintance. With many, the Tingguian is on amicable terms, while toward Kabonīyan he exhibits a degree of respect and gratitude which is close to affection. He realizes that there are many unfriendly spirits, but he has means of controlling or thwarting their evil designs; and hence he does not live in that state of perpetual fear which is so often pictured as the condition of the savage.

The Spirits of the Tingguian

A great host of unnamed spirits are known to exist; they often attend the ceremonies and sometimes enter the bodies of the alopogan , and in this way new figures appear from time to time. In addition to these, there are certain superior beings who are well known, and who, as already indicated, exercise a potent influence on the daily life of the people. The following list will serve to give some idea of these spirits and their attributes; while the names of the less important will be found in connection with the detailed description of the ceremonies.

Kadaklan (“the greatest”), a powerful male spirit, who lives in the sky, created the earth, sun, moon, and stars. The stars are only stones, but the sun and moon are lights. At times Kadaklan enters the body of a favored alopogan , and talks directly with the people; but more frequently he takes other means of communication. Oftentimes he sends his dog Kīmat, the lightening, to bite a tree or strike a field or house, and in this way makes known his wish that the owner celebrate the Padīam ceremony. All other beings are in a measure subservient to him, and his wishes are frequently made known through them. Thunder is his drum with which he amuses himself during stormy weather, but sometimes he plays on it even on clear days.

Agᴇmᴇm is the wife of Kadaklan. She lives in the ground. Little is known of her except that she has given birth to two sons, whose chief duty is to see that the commands of their father are obeyed.

Adám and Baliyen are the sons of Kadaklan. The name of the first boy is suggestive of Christian influence, but there are no traditions or further details to link him with the Biblical character.

Kabonīyan is the friend and helper of the people, and by many is classed above or identified with Kadaklan. At times he lives in the sky; again in a great cave near Patok. From this cave came the jars which could talk and move, here were found the copper gongs used in the dances, and here too grew the wonderful tree which bore the agate beads so prized by the women. This spirit gave the Tingguian rice and sugar-cane, taught them how to plant and reap, how to foil the designs of ill-disposed spirits, the words of the dīams and the details of many ceremonies. Further to bind himself to the people, it is said, he married “in the first times” a woman from Manabo. He is summoned in nearly every ceremony, and there are several accounts of his having appeared in his own form. According to one of these, he is of immense proportions; his spear is as large as a tree, and his head-axe the size of the end of the house.

Apdel is the spirit who resides in the guardian stones (pīnaing) at the gate of the town. During a ceremony, or when the men are away for a fight, it becomes his special duty to protect the village from sickness and enemies. He has been known to appear as a red rooster or as a white dog.

Īdadaya, who lives in the east (daya), is a powerful spirit who attends the Pala-an ceremony. He rides a horse, which he ties to the little structure built during the rite. Ten grand-children reside with him, and they all wear in their hair the īgam (notched feathers attached to a stick). When these feathers lose their lustre, they can only be restored by the celebration of Pala-an. Hence the owners cause some mortal, who has the right to conduct the ceremony, to become ill, and then inform him through the alopogan as to the cause of his affliction. The names of the grand-children are as follows: Pensipenondosan, Logosen, Bakoden, Bing-gasan, Bakdañgan, Giligen, Idomalo, Agkabkabayo, Ebloyan, and Agtabtabokal.

Kaiba-an is the spirit who lives in the little house or saloko in the rice-fields, and who protects the growing crops. Offerings are made to him, when a new field is constructed, when the rice is transplanted, and at harvest time. “The ground which grows” (that is the nest of the white ant) is said to be made by him.

Makaboteng, also called Sanadan, is the guardian of the deer and wild hogs. His good will is necessary if the dogs are to be successful in the chase; consequently he is summoned to many ceremonies, where he receives the most courteous treatment. In one ceremony he declared, “I can become the sunset sky.”

Sabīan or Isabīan is the guardian of the dogs.

Bisangolan (“the place of opening or tearing”) is a gigantic spirit, who lives near the river, and who in time of floods uses his head-axe and walking-stick to keep the logs and refuse from jamming. “He is very old, like the world, and he pulls out his beard with his finger nails and his knife. His seat is a wooden plate.” He appears in the Dawak, Tangpap, and Sayang ceremonies, holding a rooster and a bundle of rice. In Ba-ak he is called Ibalinsogóan, and is the first spirit summoned in Dawak.

Kakalonan, also known as Boboyonan, is the one who makes friends, and who learns the source of troubles. When summoned at the beginning of a ceremony, he tells what needs to be done, in order to insure the results desired.

Sasagangen, sometimes called Ingalit, are spirits whose business it is to take heads and put them on the saga or in the saloko. Headache is caused by them.

Abat are numerous spirits who cause sore feet and headache. Salono and bawi are built for them.

The spirits of Ībal, who live in Daem, are responsible for most sickness among children, but they are easily appeased with blood and rice. The Ībal ceremony is held for them.

Maganáwan, who lives in Nagbotobotan (“the place near which the rivers empty into the hole, where all streams go”) is one of the spirits, called in the Sangásang ceremony, and for whom the blood of the rooster mixed with rice is put into the saloko, which stands in the yard.

Ináwen is a pregnant female spirit, who lives in the sea, and who demands the blood of a chicken mixed with rice to satisfy her capricious appetite. She also attends the Sangásang.

Kīdeng is a tall, fat spirit with nine heads. He is the servant of Ináwen, and carries the gifts of mortals to his mistress.

Ībwa is an evil spirit, who once mingled with the people in human form. Due to the thoughtless act of a mourner at a funeral, he became so addicted to the taste of human flesh, that it has since then been necessary to protect the corpse from him. He fears iron, and hence a piece of that metal is always laid on the grave. Holes are burned in each garment placed on the body to keep him from stealing them.

Akop is likewise evil. He has a head, long slimy arms and legs, but no body. He always frequents the place of death, and seeks to embrace the spouse of the deceased. Should he succeed, death follows quickly. To defeat his plans, the widow is closely guarded by the wailers; she also sleeps under a fish net as an additional protection against his long fingers, and she wears seeds which are disliked by this being.

Kadongáyan indulges in the malicious sport of slitting the mouth of the corpse back to the ears. In order to frighten him away, a live chicken, with its mouth split to its throat, is placed by the door, during the time the body is in the house. When he sees the sufferings of the bird, he fears to enter the dwelling lest the people treat him in the same manner.

Sᴇlday is an ill-disposed being. He causes people to have sore feet, and only relieves them, when offerings are made to him in the saloko or bawi. He lives in the wooded hill, but quickly learns of a death, and appears at the open grave. Unless he is bought off with an offering, the blood of a small pig, he is almost certain to make away with the body, or cause a great sickness to visit the village. As the mourners return home, after the burial, they place bits of the slaughtered animal by the trail, so that he will not make them ill.

Bayon is a male spirit, who dwells in the sky, and who comes to earth as a fresh breeze. He once stole a girl from Layógan, changed her two breasts into one, placed this in the center of her chest, and married her.

Lokadáya is the human wife of Bayon. She now appears to have joined the company of the natural spirits and to be immortal. At times, both she and her husband enter the bodies of the shamans.

Agonán is the spirit who knows many dialects. He lives in Dingolowan.

Gīlen attends many ceremonies, and occupies an important place in Tangpap; yet little is known of him.

Inginlaod are spirits who live in the west.

Ginobáyan is a female spirit, always present in the Tangpap ceremony.

Sangalo is a spirit who gives good and bad signs.

Dapeg, Balingen-ngen, Benisalsal, and Kikiba-an, are all disturbers and mischief-makers. They cause illness, sore feet, headache, and bad dreams. They are important only because of the frequency with which they appear.

Al-lot attends festivals and prevents quarrels.

Liblibayan, Banbanayo, and Banbantay, are lesser spirits, who formerly aided “the people of the first times.”

The term “Alan” comprises a large body of spirits with half human, half bird-like forms. They have wings and can fly; their toes are at the back of their feet, and their fingers attach to the wrists and point backward. Often they hang from the branches of trees, like bats, but they are also pictured as having fine houses and great riches. They are sometimes hostile or mischievous, but more frequently are friendly. They play a very important part in the mythology, but not in the cult.

Komau is a giant spirit, who, according to tradition, was killed by the hero Sayen. Among the Ilocano and some of the Tingguian, the Komau is known as a great invisible bird, which steals people and their possessions. He does not visit the people through the bodies of the shamans.

Anito is a general term used to designate members of the spirit world.

A survey of the foregoing list brings out a noticeable lack of nature-spirits; of trees, rocks, and natural formations considered as animate; and of guardian spirits of families and industries. There is a strong suggestion, however, in the folk-tales to the effect that this has not always been the case; and even to-day there are some conflicts regarding the status of certain spirits.

In the village of Manabo, thunder is known as Kidol; in Likuan and Bakaok, as Kido-ol; and in each place he is recognized as a powerful spirit. In Ba-ay, two types of lightning are known to be spirits. The flash from the sky is Salit, that “from the ground” is Kilawit. Here thunder is Kadaklan, but the sun is the all powerful being. He is male, and is “so powerful that he does not need or desire ceremonies or houses.” The moon is likewise a powerful spirit, but female.

In the discussion of the tales it was suggested that these and other ideas, which differ from those held by the majority of the group, may represent older conceptions, which have been swamped, or may have been introduced into Abra by emigrants from the north and east.

The Tingguian Shaman, Alopogan (“she who covers her face”)

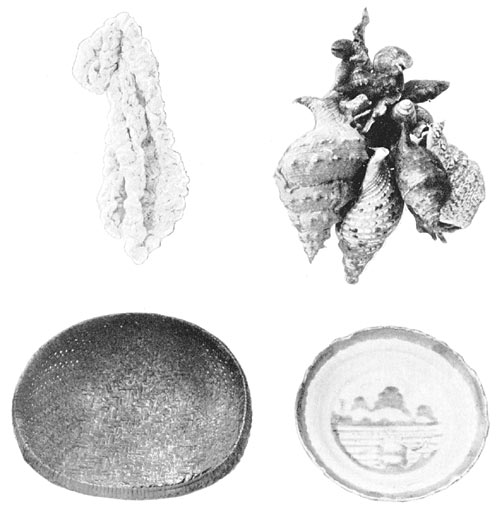

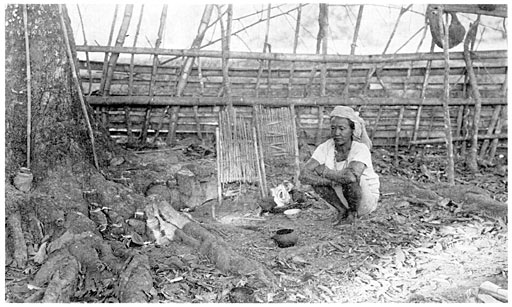

The superior beings talk with mortals through the aid of the alopogan, known individually and collectively as alopogan (“she who covers her face”). These are generally women past middle life, though men are not barred from the profession, who, when chosen, are made aware of the fact by having trembling fits when they are not cold, by warnings in dreams, or by being informed by other alopogan that they are desired by the spirits. A woman may live the greater part of her life without any idea of becoming a alopogan , and then because of such a notification will undertake to qualify. She goes to one already versed, and from her learns the details of the various ceremonies, the gifts suitable for each spirit, and the chants or dīams which must be used at certain times. This is a considerable task, for the dīams must be learned word for word; and, likewise, each ceremony must be conducted, just as it was taught by the spirits to the “people of the first times.” The training occupies several months; and when all is ready, the candidate secures her pīling. This is a collection of large sea-shells attached to cords, which is kept in a small basket together with a Chinese plate and a hundred fathoms of thread. New shells may be used, but it is preferable to secure, if possible, the pīling of a dead alopogan . Being thus supplied, the novice seeks the approval of the spirits and acceptance as a alopogan . The wishes of the higher beings are learned by means of a ceremony, in the course of which a pig is killed, and its blood mixed with rice is scattered on the ground. The liver of the animal is eagerly examined; for, if certain marks appear on it, the candidate is rejected, or must continue her period of probation for several months, before another trial can be made. During this time she may aid in ceremonies, but she is not possessed by the spirits. When finally accepted, she may begin to summon the spirits into her body. She places offerings on a mat, seats herself in front of them, and calls the attention of the spirits by striking her pīling, or a bit of lead, against a plate; then covering her face with her hands, she begins to chant. Suddenly she is possessed; and then, no longer as a human, but as the spirit itself, she talks with the people, asking and answering questions, or giving directions, as to what shall be done to avert sickness and trouble, or to bring good fortune.

Certain alopogan are visited only by low, mean spirits; others, by both good and bad; while still others may be possessed even by Kadaklan, the greatest of all. It is customary for the spirit of a deceased mortal to enter the body of a alopogan , just before the corpse is to be buried, to give messages to the family; but he seldom comes again in this manner.

The pay of a alopogan is small, usually a portion of a sacrificed animal, a few bundles of rice, and some beads; but this payment is more than offset by the restrictions placed on her. At no time may she eat of carabao, wild pig, wild chicken, or shrimp; nor may she touch peppers—all prized articles of food.

The inducements for a person to enter this vocation are so few that a candidate begins her training with reluctance; but, once accepted by the spirits, the alopogan yields herself fully and sincerely to their wishes. When possessed by a spirit, her own personality is submerged, and she does many things of which she is apparently ignorant, when she emerges from the spell. Oftentimes, as she squats by the mat, summoning the spirits, her eyes take on a far-away stare; the veins of her face and neck stand out prominently, while the muscles of her arms and legs are tense; then, as she is possessed, she assumes the character and habits of the superior being. If it is a spirit supposed to dwell in Igorot or Kalinga land, she speaks in a dialect unfamiliar to her hearers, orders them to dance in Igorot fashion, and then instructs them in dances, which she or her townspeople could never have seen. At times she carries on sleight-of-hand tricks, as when she places beads in a dish of oil, and dances with it high above her head, until the beads vanish. A day or two later she will recover them from the hair of some participant in the ceremony. Most of her acts are in accordance with a set procedure; yet at times she goes further, and does things which seem quite inexplainable.

One evening, in the village of Manabo, we were attending a ceremony. Spirit after spirit had appeared, and at their order dances and other acts had taken place. About ten o’clock a brilliant flash of lightning occurred, although it was not a stormy evening. The body of the alopogan was at that time possessed by Amangau, a head-hunting spirit. He at once stopped his dance, and announced that he had just taken the head of a boy from Luluno, and that the people of his village were even then dancing about the skull. Earlier in the evening we had noticed this lad (evidently a consumptive) among the spectators. When the spirit made this claim, we looked for him, but he had vanished. A little later we learned that he had died of a hemorrhage at about the time of the flash.

Such occurrences make a deep impression on the mind of the people, and strengthen their belief in the spirit world; but, so far as could be observed, the prestige of the alopogan was in nowise enhanced.

Since most of the ceremonies are held to keep the family or individual in good health, the alopogan takes the place of a physician. She often makes use of simple herbs and medicinal plants, but always with the idea that the treatment is distasteful to the being, who has caused the trouble, and not with any idea of its curative properties. Since magic and religion are practically the same in this society, the alopogan is the one who usually conducts or orders the magic rites; and for the same reason she, better than all others, can read the signs and omens sent by members of the spirit world.

Magic of the Tingguian

The folk-tales are filled with accounts of magical acts, performed by “the people of the first times.” They annihilated time and space, commanded inanimate objects to do their will, created human beings from pieces of betel-nut, and caused the magical increase of food and drink. Those days have passed, yet magical acts still pervade all the ceremonies; nature is overcome, while the power to work evil by other than human means is a recognized fact of daily life. In the detailed accounts of the ceremonies will be found many examples of these magical acts, but the few here mentioned will give a good idea of all.

In one ceremony, a blanket is placed over the family, and on their heads a coconut is cut in two, and the halves are allowed to fall; for, “as they drop to the ground, so does sickness and evil fall away from the people.” A bound pig is placed in the center of the floor, and water is poured into its ear that, “as it shakes out the water, so may evil spirits and sickness be thrown out of the place.” At one point in the Tangpap ceremony, a boy takes the sacrificial blood and rice from a large dish, and puts it in a number of smaller ones, then returns it again to the first; for, “when the spirits make a man sick, they take a part of his life. When they make him well, they put it back, just as the boy takes away a part of the food, gives it to the spirits, and then replaces it,” The same idea appears in the dance which follows. The boy and the alopogan take hold of a winnower, raise it in the air, and dance half way around a rice-mortar; then return, as they came, and replace it, “just as the spirits took away a part of the patient’s life, but now will put it back.”

The whole life of a child can be determined, or at least largely influenced, by the treatment given the afterbirth, while the use of bamboo and other prolific plants, at this time and at a wedding, promote growth and fertility.

A piece of charcoal attached to a certain type of notched stick is placed in the rice-seed beds, and thus the new leaves are compelled to turn the dark green color of sturdy plants.

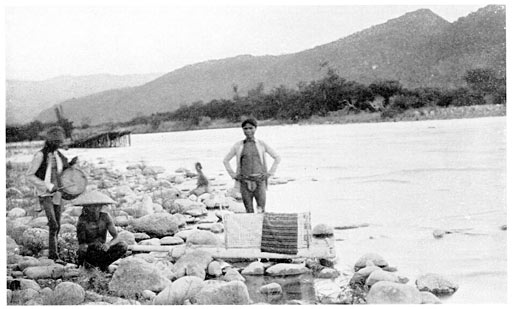

If a river is overflowing its banks, it can be controlled by cutting off a pig’s head and throwing it into the waters. An even more certain method is to have a woman, who was born on the other side of the river, take her weaving baton and plant it on the bank. The water will not rise past this barrier.

Blackening of the teeth is a semi-magical procedure. A mixture of tan-bark and iron salts is twice applied to the teeth, and is allowed to remain several hours; but, in order to obtain the desired result, it is necessary to use the mixture after nightfall and to remove it, before the cocks begin to crow, in the morning. If the fowls are heard, while the teeth are being treated, they will remain white; likewise they will refuse to take the color, should their owner approach a corpse or grave.

On well-travelled trails one often sees, at the tops of high hills, piles of stones, which have been built up during many years. As he ascends a steep slope, each traveller picks up a small stone, and carries it to the top, where he places it on the pile. As he does so, he leaves his weariness behind him, and continues his journey fresh and strong.

The use of love-charms is widespread: certain roots and leaves, when oiled or dampened with saliva, give forth a pleasant odor, which compels the affection of a woman, even in spite of her wishes.

Evil magic, known as gamot (“poison”) is also extensively used. A little dust taken from the footprint of a foe, a bit of clothing, or an article recently handled by him, is placed in a dish of water, and is stirred violently. Soon the victim begins to feel the effect of this treatment, and within a few hours becomes insane. To make him lame, it is only necessary to place poison on articles recently touched by his feet. Death or impotency can be produced by placing poison on his garments. A fly is named after a person, and is placed in a bamboo tube. This is set near the fire, and in a short time the victim of the plot is seized with fever. Likewise magical chants and dances, carried on beneath a house, may bring death to all the people of the dwelling.

A combination of true poisoning and magical practice is also found. To cause consumption or some wasting disease, a snake is killed, and its head cut off; then the body is hung up, and the liquor coming from the decomposing flesh is caught in a shell cup. This fluid is introduced into the victim’s food, or some of his belongings are treated with it. If the subject dies, his relatives may get revenge on the poisoner. This is accomplished by taking out the heart of a pig and inserting it in the mouth or stomach of the victim. This must be done under the cover of darkness, and the corpse be buried at once. A high bamboo fence is then built around the grave, so that no one can reach it. The person responsible for the death will fall ill at once, and will die unless he is able to secure one of the victim’s garments or dirt from the grave.

The actual introduction of poison in food and drink is thought to be very common. The writer attended one ceremony following which a large number of the guests fell sick. The illness was ascribed to magic poisoning, yet it was evident that the cause was over-indulgence in fresh pork by people, who for months had eaten little if any meat.

Omens of the Tingguian

The ability to foretell future events by the flight or calls of birds, actions of animals, by the condition of the liver and gall of sacrificed pigs, or by the movements of certain articles under the questioning of a alopogan , is an undoubted fact in this society.

A small bird known as labᴇg, is the messenger of the spirits, who control the Bakid and Sangásang ceremonies. When this bird enters the house, it is caught at once, its feathers are oiled; beads are attached to its feet, and it is released with the promise that the ceremony will be celebrated at once. This bird accompanies the warriors, and warns or encourages them with its calls. If it flies across their path from right to left, all is well; but if it comes from the left, they must return home, or trouble will befall the party.

The spirits of Sangásang make use of other birds and animals to warn the builders of a house, if the location selected does not please them. All the Tingguian know that the arrival of snakes, big lizards, deer, or wild hogs at the site of a new house is a bad sign.

If a party or an individual is starting on a journey, and the kingfisher (salaksak) flies from in front toward the place just left, it is a command to return at once; else illness in the village or family will compel a later return. Should the koling cry awīt, awīt (“to carry, to carry”), an immediate return is necessary, or a member of the party will die, and will be carried home. When a snake crawls across the trail, and goes into a hole, it is a certain warning that, unless the trip is given up, some of the party will die, and be buried in the ground.

The falling of a tree across the trail, when the groom is on his way to the home of his bride, threatens death for the couple, while the breaking or falling of an object during the marriage ceremony presages misfortune.

Not all the signs are evil; for, if a man is starting to hunt, or trade, and he sees a hawk fly in front of him and catch a bird or chicken, he may on that day secure all the game he can carry, or can trade on his own terms.

All the foregoing are important, but the most constantly employed method of foretelling the future is to examine the gall and liver of slain pigs. These animals are killed in all great ceremonies, at the conclusion of a alopogan’s probation period, at birth, death, and funeral observances, and for other important events. If a head-hunt is to be attempted, the gall sack is removed, and is carefully examined, for if it is large and full, and the liquor in it is bitter, the enemy will be powerless; but if the sack is small, and only partially filled with a weak liquor, it will fare ill with the warriors who go into battle. For all other events, the liver itself gives the signs. When it is full and smooth, the omens are favorable; but if it is pitted, has black specks on it, is wrinkled, or has cross lines on it, the spirits are ill-disposed, and the project should be delayed. If, however, the matter is very urgent, another pig or a fowl may be offered in the hope that the attitude of the spirits may be changed. If the liver of the new sacrifice is good, the ceremony or raid may continue. The blood of these animals is always mixed with rice, and is scattered about for the superior beings, but the flesh is cooked, and is consumed by the mortals.

To recover stolen and misplaced articles or animals, one of three methods is employed. The first is to attach a cord to a jar-cover or the shells used by a alopogan . This is suspended so that it hangs freely, and questions are put to it. If the answer is “yes,” it will swing to and fro. The second method is to place a bamboo stick horizontally on the ground and then to stand an egg on it. As the question is asked, the egg is released. If it falls, the answer is in the negative; if it stands, it replies “yes.” The third and more common way is to place a head-axe on the ground, then to blow on the end of a spear and put it point down on the blade of the axe. If it balances, the answer is “yes.”

Tingguian Ceremonial Structures

As has been indicated, the Tingguian holds many ceremonies in honor of the superior beings; and, in connection with these, builds numerous small structures, and employs various paraphernalia, most of which bear definite names, and have well established uses. Since a knowledge of these structures and devices is necessary to a full understanding of the ceremonies, an alphabetical list is here furnished, before proceeding to the detailed discussion of the rites.

Alalot: Two arches of bamboo, which support a grass roof. A small jar of basi stands in this structure for the use of visiting spirits. Is generally constructed during the Sayang ceremony, but in Bakaok it is built alone to cure sickness or to change a bad disposition.

Aligang: A four-pronged fork of a branch in which a jar of basi and other offerings are placed for the Igorot spirits of Talegteg (Salegseg). It is placed at the corner of the house during Sayang.

Ansisilit: The framework placed beside the guardian stones on the sixteenth morning of Sayang. It closely resembles the Inapapáyag.

Balabago (known in Manabo as Talagan): A long bamboo bench with a roofing of betel leaves. It is intended as a seat for guests, both spirit and human, during important ceremonies.

Balag: A seat of wood or bamboo, placed close to the house-ladder during the Sayang ceremony. Above and beside it are alangtin leaves, branches of the lanoti tree, sugar-cane, and a leafy branch of bamboo. Here also are found a net equipped with lead sinkers, a top-shaped device, and short sections of bamboo filled with liquor. In some towns this is the seat of the honored guest, who dips basi for the dancers. In San Juan this seat is called Patogaú.

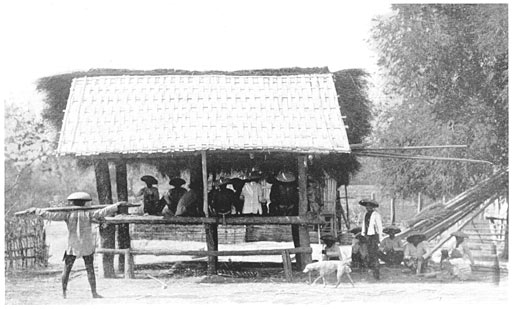

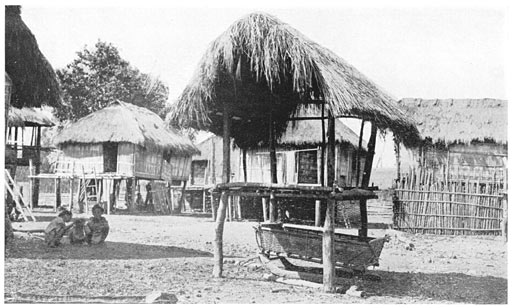

Balaua: This, the largest and most important of the spirit structures, is built during the Sayang ceremony. The roofing is of plaited bamboo, covered with cogon grass. This is supported by eight uprights, which likewise furnish attachment for the bamboo flooring. There are no sides to the building, but it is so sturdily constructed that it lasts through several seasons. Except for the times of ceremony, it is used as a lounging place for the men, or as a loom-room by the women. Quite commonly poles are run lengthwise of the structure, at the lower level of the roof; and this “attic,” as well as the space beneath the floor, is used for the storage of farming implements, bundles of rattan and thatching.

Balitang: A large seat like the Balabago, but with a grass roofing. It is used as a seat for visitors during great ceremonies and festivals. This name is applied, in Manabo, to a little house, built among the bananas for the spirit Imalbi.

Banī-īt or Bunot: Consists of a coconut husk suspended from a pole. The feathers of a rooster are stuck into the sides. It is made as a cure for sick-headache, also for lameness.

Bangbangsal: Four long bamboo poles are set in the ground, and are roofed over to make a shelter for the spirits of Sayaw, who come in the Tangpap ceremony.

Bátog: An unhusked coconut, resting on three bamboo sticks, goes by this name. It always appears in the Sayang ceremony, close to the Balag, but its use and meaning are not clear.

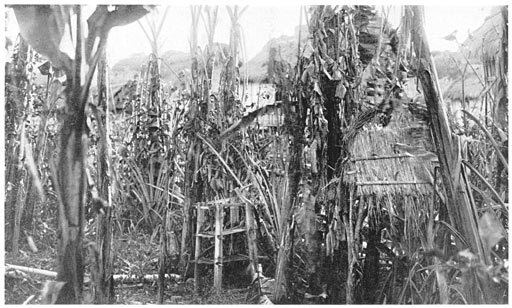

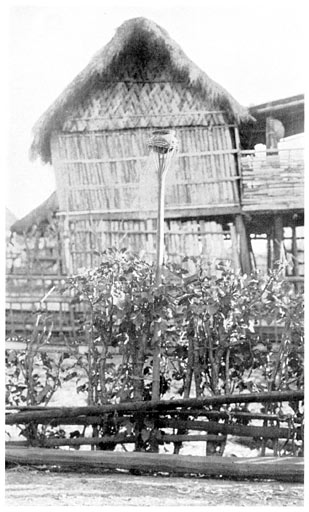

Bawi, also called Babawi, Abarong, and Sinaba-an: A name applied to any one of the small houses, built in the fields or gardens as a home for the spirits Kaiba-an, Abat, Sᴇlday, and some others of lesser importance.

Idasan: A seat or bench which stands near the house-ladder during the Sayang. A roof of cogon grass protects ten bundles of unthreshed rice, which lie on it. This rice is later used as seed. In the San Juan district, the place of the Īdasan seems to be taken by three bamboo poles, placed in tripod fashion, so as to support a basket of rice. This is known as Pinalasang.

Inapapáyag: Two-forked saplings or four reeds are arranged so as to support a shield or a cloth “roof”. During Sayang and some other ceremonies, it stands in the yard, or near to the town gate; and on it food and drink are placed for visiting spirits. During the celebration of Layog, it is built near to the dancing space, and contains offerings for the spirit of the dead. A spear with a colored clout is stuck into the ground close by; and usually an inverted rice mortar also stands here, and supports a dish of basi. In the mountain village of Likuan it is built alone as a cure for sickness. A pig is killed and the alopogan summon the spirits as in Dawak.

Kalang: A wooden box, the sides of which are cut to resemble the head and horns of a carabao. The spirits are not thought to reside here, but do come to partake of the food and drink placed in it. It is attached to the roof of the dwelling or in the balaua or kalangan. New offerings are placed in the kalang, before the men go to fight, or when the Sayang ceremony is held. It also holds the head-bands worn by the alopogan , when making Dawak.

Kalangan: the place of the kalang. This is similar to the balaua, but is smaller and, as a rule, has only four supporting timbers.

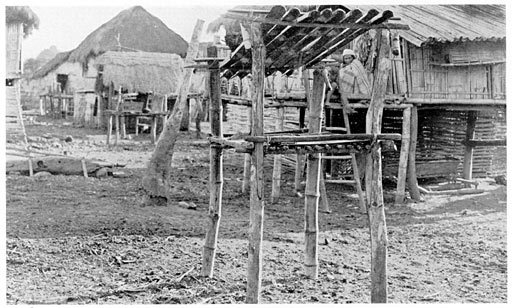

Pala-an: Four long poles, usually three of bamboo, and one of a resinous tree known as anteng (Canarium villosum Bl.) are set in a square and support, near the top, a platform of bamboo. Offerings are made both on and below the Pala-an during the ceremony of that name, and in the more important rites.

Pangkew: Three bamboo poles are planted in the ground in a triangle, but they lean away from each other at such an angle, as to admit of a small platform midway of their length. A roofing of cogon grass completes the structure. It is built during Sayang, and contains a small jar of basi. The roof is always adorned with coconut blossoms.

Sagang: Sharpened bamboo poles about eight feet in length on which the skulls of enemies were formerly exhibited. The pointed end was pushed through the foramen magnum, and the pole was then planted near the gate of the town.

Saloko, also called Salokang and Sabut: This is a bamboo pole about ten feet long, one end of which is split into several strips; these are forced apart, and are interwoven with other strips, thus forming a sort of basket. When such a pole is erected near to a house, or at the gate of the town, it is generally in connection with a ceremony made to cure headache. It is also used in the fields as a dwelling place for the spirit Kaiba-an. The Saloko ceremony and the dīam, which accompanies it, seem to indicate that this pole originated in connection with head-hunting; and its presence in the fields gives a hint that in former times a head-hunt may have been a necessary preliminary to the rice-planting.

Sogáyob: A covered porch, which is built along one side of the house during the Sayang ceremony. In it hang the vines and other articles, used by the female dancers in one part of the rite. A portion of one of the slaughtered pigs is placed here for the spirits of Bangued. In Lumaba the Sogáyob is built alone as a part of a one-day ceremony; while in Sallapadan it follows Kalangan after an interval of about three months.

Taltalabong: Following many ceremonies a small bamboo raft with arched covering is constructed. In it offerings are placed for spirits, who have been unable to attend the rite. In Manabo it is said that the raft is intended particularly for the sons of Kadaklan.

Tangpap: Two types of structure appear under this name. When it is built as a part of the Tangpap ceremony, it is a small house with a slanting roof resting on four poles. About three feet above the ground, an interwoven bamboo floor is lashed to the uprights. In the Sayang ceremony, there are two structures which go by this name. The larger has two floors, the smaller only one. On each floor is a small pot of basi, daubed with white.

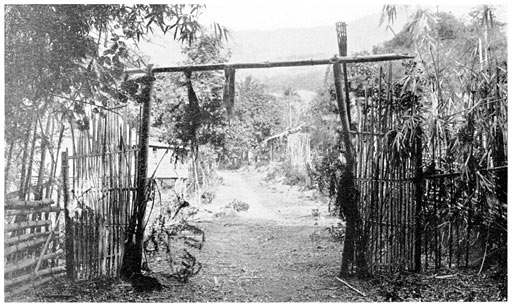

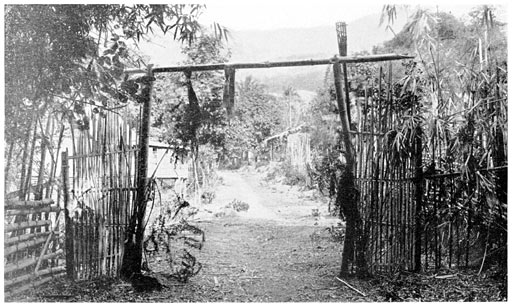

Taboo Gateway: At the gate of a town, one sometimes finds a defensive wall of bamboo, between the uprights of which are thrust bamboo spears in order to catch evil spirits, while on the gate proper are vines and leaves pleasing to the good spirits. Likewise in the saloko, which stands close by, are food and drink or betel-nut. All this generally appears when an epidemic is in a nearby village, in order to frighten the bearers of the sickness away, and at the same time gain the aid of well-disposed spirits. At such a time many of the people wear wristlets and anklets of bamboo, interwoven with roots and vines which are displeasing to the evil beings.

Tingguian Ceremonial Items:

Akosan (Fig. 4, No. 4): A prized shell, with top and bottom cut off, is slipped over a belt-like cloth. Above it are a series of wooden rings and a wooden imitation of the shell. This, when hung beside the dead, is both pleasing to the spirit of the deceased, and a protection to the corpse against evil beings.

Aneb (Fig. 4, No. 1): The name usually given to a protective necklace placed about the neck of a young child to keep evil spirits at a distance. The same name is also given to a miniature shield, bow and arrow, which hang above the infant.

Dakīdak (Fig. 4, Nos. 3–3a): Long poles, one a reed, the other bamboo, split at one end so they will rattle. The alopogan strikes them on the ground to attract the spirits to the food served on the talapītap.

Īgam: Notched feathers, often with colored yarn at the ends, attached to sticks. These are worn in the hair during the Pala~an and Sayang ceremonies, to please the spirits of the east, called Īdadaya.

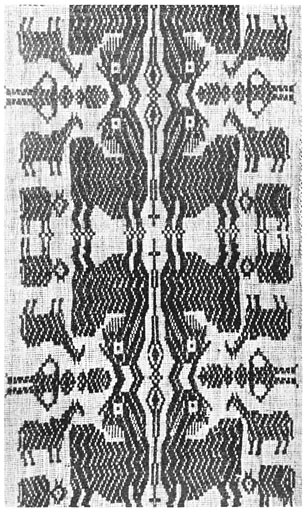

Inálson: A sacred blanket made of white cotton. A blue or blue and red design is formed, where the breadths join, and also along the borders. It is worn over the shoulders of the alopogan during the Gīpas ceremony.

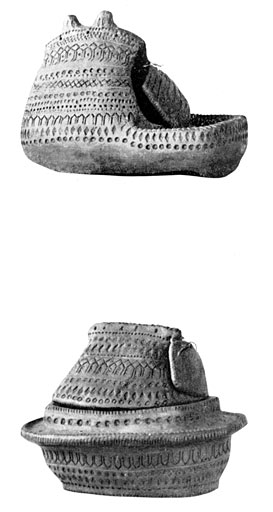

Lab-labón: Also called Adug. In Buneg and nearby towns, whose inhabitants are of mixed Tingguian and Kalinga blood, small incised pottery houses are found among the rice jars, and are said to be the residences of the spirits, who multiply the rice. They are sometimes replaced with incised jars decorated with vines. The idea seems to be an intrusion into the Tingguian belt. The name is probably derived from lábon, “plenty” or “abundance”.

Pīling: A collection of large sea-shells attached to cords. They are kept in a small basket together with one hundred fathoms of thread and a Chinese plate, usually of ancient make. The whole makes up the alopogan’s outfit, used when she is summoning the spirits.

Pīnapa: A large silk blanket with yellow strips running lengthwise. Such blankets are worn by certain women when dancing da-eng, and they are also placed over the feet of a corpse.

Sado (Fig. 4, No. 3): The shallow clay dishes in which the spirits are fed on the talapītap.

Salogeygey: The outside bark of a reed is cut at two points, from opposite directions, so that a double fringe of narrow strips stands out. One end is split, saklag leaves are inserted, and the whole is dipped or sprinkled in sacrificial blood, and placed in each house during the Sagobay ceremony. The same name is applied to the magical sticks, which are placed in the rice seed-beds to insure lusty plants.

Sangádel: The bamboo frame on which a corpse is placed during the funeral.

Tabing: A large white blanket with which one corner of the room is screened off during the Sayang and other ceremonies. In this “room” food and other offerings are made for the black, deformed, and timid spirits who wish to attend the ceremony unobserved.

Takal: Armlets made of boar’s tusks, which are worn during certain dances in Sayang.

Talapītap (Fig. 4, No. 3): A roughly plaited bamboo frame on which the spirits are fed during the more important rites. Used in connection with the dakīdak and clay dishes (sado).

Tongátong (Fig. 4, No. 5): The musical instrument, which appears in many ceremonials. It consists of six or more bamboo tubes of various lengths. The players hold a tube in each hand, and strike their ends on a stone, which lies between them, the varying lengths of the cylinders giving out different notes.

SOURCE: The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe, Fay-Cooper Cole, Assistant Curator of Malayan Ethnology 1922

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.